Archive for March, 2017

French Disaster Plans: Dealing With the Paris Terror Attacks (Red, Yellow, and White Plans)

Monday, March 27th, 2017In the event of a disaster in France, two complementary plans are activated: the Red Plan and the White Plan.

The Red Plan concerns what is happening in the field. It is based on the principle of extracting and grouping the injured. The injured are grouped in the field hospital, the triage and care center where the treatment that is strictly necessary is given, to ensure survival, calm the pain, and be able to transport the victims without making their condition worse. The field hospital is placed under the authority of the medical response coordinating physician.

The Alpha Red Plan, such as that activated on the night of November 13, is designed to deal with multisite events.

The Yellow Plan is a variant of the Red Plan adapted to nuclear, radiological, biological, and chemical risks. At the same time, the hospitals must be prepared to deal with an influx of victims: this is the responsibility of the White Plan.

On November 13, the emergency services counted 479 victims: operations on chronic cases therefore had to be put on hold in order to deal with the urgent cases.

The White Plan includes setting up a unit tasked with communication with the media, informing families, programming the release of beds, calling in reinforcements, etc. In line with the Social Security Modernization Act of 2004, the White Plan was extended to cover all establishments around the hospital, including clinics

About the devastating series of attacks that struck Paris and Saint Denis on the evening of Friday, November 13, at six different locations, with 132 dead so far and more than 250 injured

Monday, March 27th, 2017“….The White Plan has been enshrined in law since 2004 and enables additional means and human resources to be mobilized, nonessential activities to be rescheduled, and additional beds to be opened.

|

|

“All the personnel are mobilized, in particular the [Service d’Aide Médicale Urgente] and A&E teams. The necessary staff are called in directly by the hospitals,” the AP-HP stated in a press release Friday evening. All the emergency services of the largest university hospital in France were mobilized. The victims of the attacks were mainly distributed among Saint-Louis Hospital, La Pitié Salpêtrière Hospital, Georges Pompidou European Hospital, Henri Mondor Hospital, Lariboisière Hospital, Saint-Antoine Hospital, Bichat Hospital, and Beaujon Hospital…..

On Saturday, November 14, at least 300 people were being treated in Paris hospitals, with 80 of them being considered absolute emergencies and 177 relative emergencies, plus 43 additional persons — either witnesses or family members.

AP-HP issued the somber warning that “most of the patients are in a state of shock and suffering from various and sometimes multiple injuries, which could require very long-term medical attention.” By late afternoon on Sunday, November 15, about 415 people, or about 100 more than the previous day, had been admitted to the hospitals for psychological shock. Of the 80 absolute emergency cases, 35 had been downgraded, but an additional three had died, raising the death toll from the attacks to 132. Of the 415 persons receiving treatment, 218 were discharged on Sunday evening.

In addition to the medical community, the residents of the Paris area as a whole made a commitment to the medical effort. Although blood reserves were announced by AP-HP as being sufficient on Friday evening, large numbers of the population nonetheless lined up to give blood. The French blood bank noted that “this mobilization needs to be a long-term one: 10,000 blood donations are required every day, and all blood groups are needed.” The Ministry for Health, for its part, stated that the ministry’s health emergency center had been immediately activated, along with the health emergencies preparation and response facility. “Medico-psychological emergency units…were set up on a number of Paris sites, in order to treat the victims and their families,” the ministry added……

Last Friday, in barely 1 hour, the staffing levels had been doubled. The triage system also enabled the injured to be evenly distributed, with the largest hospitals taking several dozens of the injured, which was not a strain on the hospitals. Even if treatment of the injured at the time went smoothly, Dr Prudhomme is concerned that the hospitals could be submerged by those suffering from the psychological shock: “We could see thousands of people suffering from psychological distress, and we do not necessarily have the resources.”…..”

Brazil: Like malaria or yellow fever, Zika is a continuing threat rather than an urgent pandemic.

Sunday, March 26th, 2017“….And doctors and researchers are just starting to grasp the medical consequences of Zika. Besides the alarmingly small heads characteristic of microcephaly, many babies have a long list of varied symptoms, leading experts to rename their condition “congenital Zika syndrome.” They can have seizures, breathing problems, trouble swallowing, weakness and stiffness in muscles and joints preventing them from even lifting their heads, clubbed feet, vision and hearing problems, and ferocious irritability.

Some have passed their first birthdays, but have neurological development closer to that of 3-month-old infants, doctors say. Some microcephaly cases appear so dire that experts liken them to a previously rare variant called “fetal brain disruption sequence.” And new issues keep cropping up, including hydrocephalus,…..”

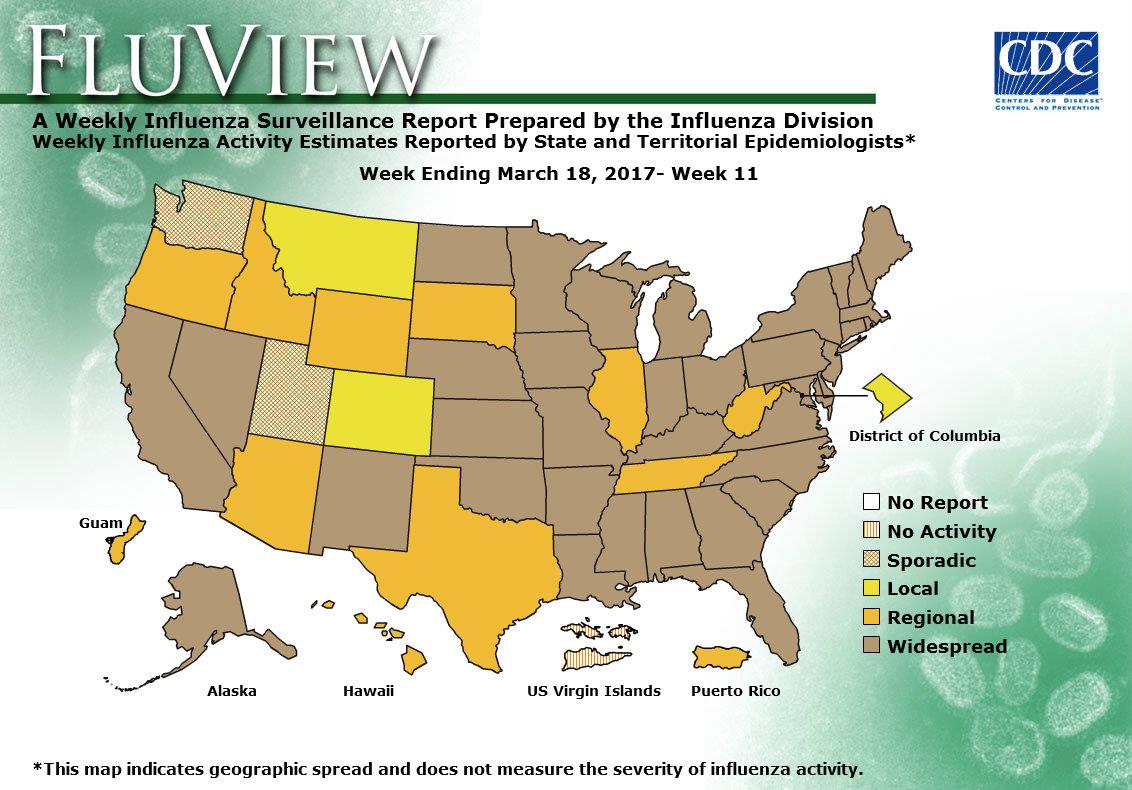

2016-2017 Influenza Season Week 11 ending March 18, 2017

Sunday, March 26th, 2017Synopsis:

During week 11 (March 12-18, 2017), influenza activity decreased, but remained elevated in the United States.

- Viral Surveillance: The most frequently identified influenza virus subtype reported by public health laboratories during week 11 was influenza A (H3). The percentage of respiratory specimens testing positive for influenza in clinical laboratories decreased.

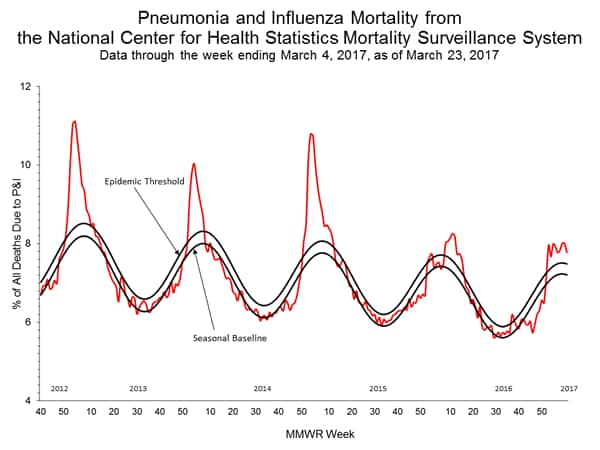

- Pneumonia and Influenza Mortality: The proportion of deaths attributed to pneumonia and influenza (P&I) was above the system-specific epidemic threshold in the National Center for Health Statistics (NCHS) Mortality Surveillance System.

- Influenza-associated Pediatric Deaths: Two influenza-associated pediatric deaths were reported.

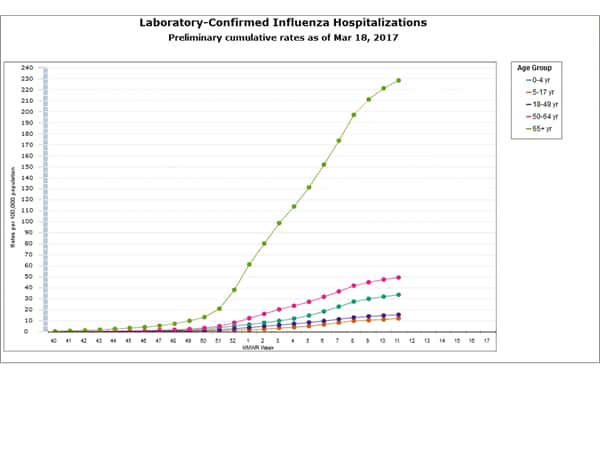

- Influenza-associated Hospitalizations: A cumulative rate for the season of 50.4 laboratory-confirmed influenza-associated hospitalizations per 100,000 population was reported.

- Outpatient Illness Surveillance: The proportion of outpatient visits for influenza-like illness (ILI) was 3.2%, which is above the national baseline of 2.2%. Seven of ten regions reported ILI at or above their region-specific baseline levels. 12 states experienced high ILI activity; six states experienced moderate ILI activity; nine states experienced low ILI activity; New York City, Puerto Rico, and 23 states experienced minimal ILI activity; and the District of Columbia had insufficient data.

- Geographic Spread of Influenza: The geographic spread of influenza in 36 states was reported as widespread; Guam, Puerto Rico and 10 states reported regional activity; the District of Columbia and two states reported local activity; two states reported sporadic activity; and the U.S. Virgin Islands reported no activity.

Why drug-resistant tuberculosis?

Sunday, March 26th, 2017The epidemiology, pathogenesis, transmission, diagnosis, and management of multidrug-resistant, extensively drug-resistant, and incurable tuberculosis

Dheda, Keertan et al.

The Lancet Respiratory Medicine , Volume 5 , Issue 4 , 291 – 360

DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S2213-2600(17)30079-6

Global tuberculosis incidence has declined marginally over the past decade, and tuberculosis remains out of control in several parts of the world including Africa and Asia. Although tuberculosis control has been effective in some regions of the world, these gains are threatened by the increasing burden of multidrug-resistant (MDR) and extensively drug-resistant (XDR) tuberculosis. XDR tuberculosis has evolved in several tuberculosis-endemic countries to drug-incurable or programmatically incurable tuberculosis (totally drug-resistant tuberculosis). This poses several challenges similar to those encountered in the pre-chemotherapy era, including the inability to cure tuberculosis, high mortality, and the need for alternative methods to prevent disease transmission. This phenomenon mirrors the worldwide increase in antimicrobial resistance and the emergence of other MDR pathogens, such as malaria, HIV, and Gram-negative bacteria. MDR and XDR tuberculosis are associated with high morbidity and substantial mortality, are a threat to health-care workers, prohibitively expensive to treat, and are therefore a serious public health problem. In this Commission, we examine several aspects of drug-resistant tuberculosis. The traditional view that acquired resistance to antituberculous drugs is driven by poor compliance and programmatic failure is now being questioned, and several lines of evidence suggest that alternative mechanisms—including pharmacokinetic variability, induction of efflux pumps that transport the drug out of cells, and suboptimal drug penetration into tuberculosis lesions—are likely crucial to the pathogenesis of drug-resistant tuberculosis. These factors have implications for the design of new interventions, drug delivery and dosing mechanisms, and public health policy. We discuss epidemiology and transmission dynamics, including new insights into the fundamental biology of transmission, and we review the utility of newer diagnostic tools, including molecular tests and next-generation whole-genome sequencing, and their potential for clinical effectiveness. Relevant research priorities are highlighted, including optimal medical and surgical management, the role of newer and repurposed drugs (including bedaquiline, delamanid, and linezolid), pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic considerations, preventive strategies (such as prophylaxis in MDR and XDR contacts), palliative and patient-orientated care aspects, and medicolegal and ethical issues.

March 25, 1911: the Triangle Shirtwaist Company factory in New York City burns down, killing 145 workers.

Saturday, March 25th, 2017Portrait of a Terrorist

Saturday, March 25th, 2017- Adrian Russell Ajao = Khalid Masood after converting to Islam in his late 30s

- 52-year-old husband and father.

- Prone to violent outbursts as a younger man

- Led a quiet life in recent years

- Most afternoons he would pick up his two youngest children from primary school in a quiet suburban part of Birmingham, in the West Midlands of England.

- “When he spoke about religion,” said a neighbor who did not want to be identified for fear of reprisals, “he suddenly was a different man,” describing in those moments a fierce and uncompromising anger about the treatment of Muslims.

Trump & Deadly Disease

Saturday, March 25th, 2017- “…..President Trump’s budget would cut funding for the National Institutes of Health by 18 percent.

- It would cut the State Department and the United States Agency for International Development, a key vehicle for preventing and responding to outbreaks before they reach our shores, by 28 percent.

- And the repeal of the Affordable Care Act would kill the billion-dollar Prevention and Public Health Fund, which provides funding for the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention to fight outbreaks of infectious disease.

- (While the budget also calls for the creation of an emergency fund to respond to outbreaks, there is no indication that it would offset the other cuts, or where the money would come from.)

- We are already witnessing an outbreak of influenza in birds — the H7N9 strain, in China — that could be the source for the next human pandemic. Since October, over 500 people have been infected; more than 34 percent have died. Most victims had contact with infected poultry, yet three recent clusters appear to be from person-to-person transmission. Will H7N9 mutate to become easily transmitted between humans? We don’t know. But without sufficient supplies of a vaccine, we are not prepared to stop it…….”

2016: Map of the Migration of Refugees into Europe

Saturday, March 25th, 2017

Key Migration Terms

Assimilation – Adaptation of one ethnic or social group – usually a minority – to another. Assimilation involves the subsuming of language, traditions, values, mores and behaviour or even fundamental vital interests. Although the traditional cultural practices of the group are unlikely to be completely abandoned, on the whole assimilation will lead one group to be socially indistinguishable from other members of the society. Assimilation is the most extreme form of acculturation.

Assisted Voluntary Return – Administrative, logistical, financial and reintegration support to rejected asylum seekers, victims of trafficking in human beings, stranded migrants, qualified nationals and other migrants unable or unwilling to remain in the host country who volunteer to return to their countries of origin.

Asylum seeker – A person who seeks safety from persecution or serious harm in a country other than his or her own and awaits a decision on the application for refugee status under relevant international and national instruments. In case of a negative decision, the person must leave the country and may be expelled, as may any non-national in an irregular or unlawful situation, unless permission to stay is provided on humanitarian or other related grounds.

Border management – Facilitation of authorized flows of persons, including business people, tourists, migrants and refugees, across a border and the detection and prevention of irregular entry of non-nationals into a given country. Measures to manage borders include the imposition by States of visa requirements, carrier sanctions against transportation companies bringing irregular migrants to the territory, and interdiction at sea. International standards require a balancing between facilitating the entry of legitimate travellers and preventing that of travellers entering for inappropriate reasons or with invalid documentation.

Brain drain – Emigration of trained and talented individuals from the country of origin to another country resulting in a depletion of skills resources in the former.

Brain gain – Immigration of trained and talented individuals into the destination country. Also called “reverse brain drain”.

Capacity building – Building capacity of governments and civil society by increasing their knowledge and enhancing their skills. Capacity building can take the form of substantive direct project design and implementation with a partner government, training opportunities, or in other circumstances facilitation of a bilateral or multilateral agenda for dialogue development put in place by concerned authorities. In all cases, capacity building aims to build towards generally acceptable benchmarks of management practices.

Circular migration – The fluid movement of people between countries, including temporary or long-term movement which may be beneficial to all involved, if occurring voluntarily and linked to the labour needs of countries of origin and destination.

Country of origin – The country that is a source of migratory flows (regular or irregular).

Emigration – The act of departing or exiting from one State with a view to settling in another.

Facilitated migration – Fostering or encouraging of regular migration by making travel easier and more convenient. This may take the form of a streamlined visa application process, or efficient and well-staffed passenger inspection procedures.

Forced migration – A migratory movement in which an element of coercion exists, including threats to life and livelihood, whether arising from natural or man-made causes (e.g. movements of refugees and internally displaced persons as well as people displaced by natural or environmental disasters, chemical or nuclear disasters, famine, or development projects).

Freedom of movement – A human right comprising three basic elements: freedom of movement within the territory of a country (Art. 13(1), Universal Declaration of Human Rights, 1948: “Everyone has the right to freedom of movement and residence within the borders of each state.”), the right to leave any country and the right to return to his or her own country (Art. 13(2), Universal Declaration of Human Rights, 1948: “Everyone has the right to leave any country, including his own, and to return to his country. See also Art. 12, International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights. Freedom of movement is also referred to in the context of freedom of movement arrangements between States at the regional level (e.g. European Union).

Immigration – A process by which non-nationals move into a country for the purpose of settlement.

Internally Displaced Person (IDP) – Persons or groups of persons who have been forced or obliged to flee or to leave their homes or places of habitual residence, in particular as a result of or in order to avoid the effects of armed conflict, situations of generalized violence, violations of human rights or natural or human-made disasters, and who have not crossed an internationally recognized State border (Guiding Principles on Internal Displacement, UN Doc E/CN.4/1998/53/Add.2.). See also de facto refugees, displaced person, externally displaced persons, uprooted people.

International minimum standards – The doctrine under which non-nationals benefit from a group of rights directly determined by public international law, independently of rights internally determined by the State in which the non-national finds him or herself. A State is required to observe minimum standards set by international law with respect to treatment of non-nationals present on its territory (or the property of such persons), (e.g. denial of justice, unwarranted delay or obstruction of access to courts are in breach of international minimum standards required by international law). In some cases, the level of protection guaranteed by the international minimum standard may be superior to that standard which the State grants its own nationals.

Irregular migration – Movement that takes place outside the regulatory norms of the sending, transit and receiving countries. There is no clear or universally accepted definition of irregular migration. From the perspective of destination countries it is entry, stay or work in a country without the necessary authorization or documents required under immigration regulations. From the perspective of the sending country, the irregularity is for example seen in cases in which a person crosses an international boundary without a valid passport or travel document or does not fulfil the administrative requirements for leaving the country. There is, however, a tendency to restrict the use of the term “illegal migration” to cases of smuggling of migrants and trafficking in persons.

Labour migration – Movement of persons from one State to another, or within their own country of residence, for the purpose of employment. Labour migration is addressed by most States in their migration laws. In addition, some States take an active role in regulating outward labour migration and seeking opportunities for their nationals abroad.

Migrant – IOM defines a migrant as any person who is moving or has moved across an international border or within a State away from his/her habitual place of residence, regardless of (1) the person’s legal status; (2) whether the movement is voluntary or involuntary; (3) what the causes for the movement are; or (4) what the length of the stay is. IOM concerns itself with migrants and migration‐related issues and, in agreement with relevant States, with migrants who are in need of international migration services.

Migration – The movement of a person or a group of persons, either across an international border, or within a State. It is a population movement, encompassing any kind of movement of people, whatever its length, composition and causes; it includes migration of refugees, displaced persons, economic migrants, and persons moving for other purposes, including family reunification.

Migration management – A term used to encompass numerous governmental functions within a national system for the orderly and humane management for cross-border migration, particularly managing the entry and presence of foreigners within the borders of the State and the protection of refugees and others in need of protection. It refers to a planned approach to the development of policy, legislative and administrative responses to key migration issues.

Naturalization – Granting by a State of its nationality to a non-national through a formal act on the application of the individual concerned. International law does not provide detailed rules for naturalization, but it recognizes the competence of every State to naturalize those who are not its nationals and who apply to become its nationals.

Orderly migration – The movement of a person from his or her usual place of residence to a new place of residence, in keeping with the laws and regulations governing exit of the country of origin and travel, transit and entry into the destination or host country.

Push-pull factors – Migration is often analysed in terms of the “push-pull model”, which looks at the push factors, which drive people to leave their country (such as economic, social, or political problems) and the pull factors attracting them to the country of destination.

Receiving country – Country of destination or a third country. In the case of return or repatriation, also the country of origin. Country that has accepted to receive a certain number of refugees and migrants on a yearly basis by presidential, ministerial or parliamentary decision.

Refugee – A person who, “owing to a well-founded fear of persecution for reasons of race, religion, nationality, membership of a particular social group or political opinions, is outside the country of his nationality and is unable or, owing to such fear, is unwilling to avail himself of the protection of that country. (Art. 1(A)(2), Convention relating to the Status of Refugees, Art. 1A(2), 1951 as modified by the 1967 Protocol). In addition to the refugee definition in the 1951 Refugee Convention, Art. 1(2), 1969 Organization of African Unity (OAU) Convention defines a refugee as any person compelled to leave his or her country “owing to external aggression, occupation, foreign domination or events seriously disturbing public order in either part or the whole of his country or origin or nationality.” Similarly, the 1984 Cartagena Declaration states that refugees also include persons who flee their country “because their lives, security or freedom have been threatened by generalised violence, foreign aggression, internal conflicts, massive violations of human rights or other circumstances which have seriously disturbed public order.”

Remittances – Monies earned or acquired by non-nationals that are transferred back to their country of origin.

Repatriation – The personal right of a refugee, prisoner of war or a civil detainee to return to his or her country of nationality under specific conditions laid down in various international instruments (Geneva Conventions, 1949 and Protocols, 1977, the Regulations Respecting the Laws and Customs of War on Land, Annexed to the Fourth Hague Convention, 1907, human rights instruments as well as customary international law). The option of repatriation is bestowed upon the individual personally and not upon the detaining power. In the law of international armed conflict, repatriation also entails the obligation of the detaining power to release eligible persons (soldiers and civilians) and the duty of the country of origin to receive its own nationals at the end of hostilities. Even if treaty law does not contain a general rule on this point, it is today readily accepted that the repatriation of prisoners of war and civil detainees has been consented to implicitly by the interested parties. Repatriation as a term also applies to diplomatic envoys and international officials in time of international crisis as well as expatriates and migrants.

Resettlement – The relocation and integration of people (refugees, internally displaced persons, etc.) into another geographical area and environment, usually in a third country. In the refugee context, the transfer of refugees from the country in which they have sought refuge to another State that has agreed to admit them. The refugees will usually be granted asylum or some other form of long-term resident rights and, in many cases, will have the opportunity to become naturalized.

Smuggling – “The procurement, in order to obtain, directly or indirectly, a financial or other material benefit, of the illegal entry of a person into a State Party of which the person is not a national or a permanent resident” (Art. 3(a), UN Protocol Against the Smuggling of Migrants by Land, Sea and Air, supplementing the United Nations Convention against Transnational Organized Crime, 2000). Smuggling, contrary to trafficking, does not require an element of exploitation, coercion, or violation of human rights.

Technical cooperation – Coordinated action in which two or several actors share information and expertise on a given subject usually focused on public sector functions (e.g. development of legislation and procedures, assistance with the design and implementation of infrastructure, or technological enhancement).

Trafficking in persons – “The recruitment, transportation, transfer, harbouring or receipt of persons, by means of the threat or use of force or other forms of coercion, of abduction, of fraud, of deception, of the abuse of power or of a position of vulnerability or of the giving or receiving of payments or benefits to achieve the consent of a person having control over another person, for the purpose of exploitation” (Art. 3(a), UN Protocol to Prevent, Suppress and Punish Trafficking in Persons, Especially Women and Children, Supplementing the UN Convention against Transnational Organized Crime, 2000). Trafficking in persons can take place within the borders of one State or may have a transnational character.

Xenophobia – At the international level, no universally accepted definition of xenophobia exists, though it can be described as attitudes, prejudices and behaviour that reject, exclude and often vilify persons, based on the perception that they are outsiders or foreigners to the community, society or national identity. There is a close link between racism and xenophobia, two terms that can be hard to differentiate from each other.

Sources

| 1 | IOM, Glossary on Migration, International Migration Law Series No. 25, 2011 |

At least 435 students fell ill of suspected food poisoning in public schools across Egypt on Tuesday and Wednesday after consuming government-issued school meals.

Saturday, March 25th, 2017“…..Egypt’s Health Ministry announced on Wednesday that 312 students in schools in Cairo, Suez and Aswan were hospitalized with symptoms of food poisoning, in a succession of mass food poisoning incidents that started earlier this month caused by the school meals, produced by a military-owned company. Some 2,200 students were treated last week for the same symptoms in the southern province of Sohag.

The manager of Beni Suef’s central hospital, Mohamed el-Gebaly, told The Associated Press that 25 students from the province south of Cairo are in stable condition and being treated for vomiting and stomach pain……”