From 30 April through 30 May 2018, a total of 16 confirmed and suspected cases (one confirmed and 15 suspected cases) were reported to the Directorate of Control of Epidemic and Pandemic diseases (DLMEP). These cases were located in five districts of Cameroon: Njikwa Health district (n=6 suspected, n=1 confirmed) Akwaya Health District (n=6 suspected), Biyem-Assi Health District (n=1 suspected), Bertoua Health District (n=1 suspected), and Fotokol Health district (n=1 suspected).

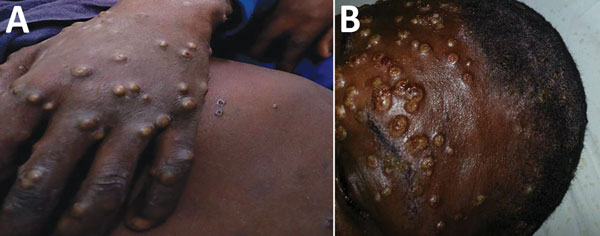

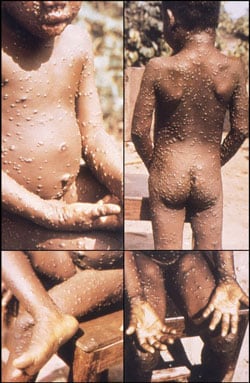

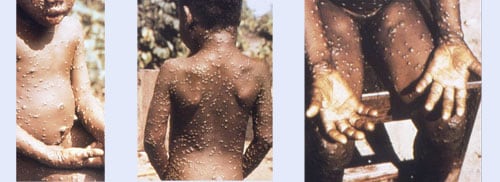

On 14 May, one of the 16 cases tested positive by reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) from the Centre Pasteur du Cameroun (CPC). The case was located in Njikwa Health District. The confirmed case is a 20-year-old male with clinical symptoms of fever, generalized vesiculo-pustular rash and enlarged lymph nodes with no previous history of travel or contact with an animal suspected of having monkeypox.

The age of the 16 cases range from one month to 58 years old, with a median age of 13 years old. Nearly half of the 16 cases are male, of which, nine are men and seven are women. Additionally, all cases had a fever and a body rash. No deaths were reported.

Public health response

WHO has activated coordination, operational and planning pillars as a part of their response mechanism:

- On 15 May 2018, the first coordination meeting was held at the Ministry of Health (MOH) to discuss and prioritise response activities. During this meeting the Incident Management System (IMS) was activated.

- An Incident Action Plan was developed for the interventions and the needs of the different sections of the response (coordination, planning, operations, logistics, communication).

- As of 30 April 2018, an epidemiological investigation of the cases are being conducted.

- Training of healthcare workers on infection control (using personal protective equipment and hand hygiene) has been implemented. Information related to isolation of cases, symptomatic case management and handwashing technique have been shared.

- Risk communication materials and a communication plan have been developed (increasing public awareness to take precautionary measure to prevent monkeypox infection).

- On 22 May, the Regional Center for Epidemics Prevention and Control (CERPLE) organised follow-up meetings, where the Njikwa Health District team gave an update from the field and other relevant feedback. WHO and UNICEF delegates attended.

WHO risk assessment

Monkeypox, a rare zoonosis occurs sporadically in forested areas of Central and West Africa. It was first detected in monkeys in Africa in 1958. The disease is caused by orthopoxvirus and has manifestations similar to human smallpox (eradicated since 1980), however human monkeypox is less severe. The disease is self-limiting with symptoms usually resolving within 14–21 days. Treatment is supportive. The virus is transmitted through direct contact with blood, bodily fluids and cutaneous/mucosal lesions of an infected person or animals, mainly African rodents or monkeys. Secondary human-to-human transmission is limited but can occur via exposure to, infectious oropharyngeal exudates and contact with infected persons during the rash phase of illness or contaminated materials. There are no specific treatments or vaccines available for monkeypox infection but outbreaks can be controlled.

The detection of monkeypox in Cameroon underscores the need to maintain high level of vigilance and raise awareness of the disease among the local population. Communication and education for people on how to prevent infection by avoiding contact with wild animals particularly rodents and primates are important. Healthcare workers should follow standard precautions when taking care of symptomatic patients and isolate them. The cases are reported from rural areas where occupational activities such as farming and hunting are increasing the risk of animal-to-human transmission.

WHO will continue to evaluate the epidemiological situation and support the implementation of prevention and response measures in collaboration with national governments and partners.

WHO advice

People in contact with animals potentially infected with monkeypox are most at-risk. During monkeypox outbreaks, respiratory droplets and direct contact with body fluids, skin lesions of patients or objects such as clothing recently contaminated by patient secretions or lesion fluids is the most significant risk factor for human-to-human transmission. In the absence of specific treatment or a vaccine, the only way to reduce infection in people is by raising public awareness of the risk factors, such as close contact with wildlife animals including rodents, and educating people about the measures they can take to reduce exposure to the virus. Surveillance measures and rapid identification of new cases is critical for outbreak containment. Public health educational messages should focus on the following risks:

- Reducing the risk of animal-to-human transmission. Efforts to prevent transmission in endemic regions should focus on avoiding eating or touching animals that are sick of found dead in the wild. Gloves and other appropriate protective clothing should be worn while handling sick animals or their infected tissues.

- Reducing the risk of human-to-human transmission. People infected with monkeypox should be isolated and infection prevention and control measures should be implemented in healthcare facilities caring for infected patients. Close physical contact with persons infected with monkeypox should be limited and gloves, face masks and protective gowns should be worn when taking care of ill people in any setting. Regular hand washing should be carried out after caring for or visiting sick people.

Health-care workers caring for patients with suspected or confirmed monkeypox virus infection or handling collected specimens should implement standard infection control precautions.

Given the location of the outbreak in a relatively remote and sparsely populated area at this stage, the risk of spread is limited. WHO does not recommend any restriction for travel and trade to Cameroon based on available information at this point in time.

For more information on monkeypox, please see the link below: