Archive for the ‘Pandemic’ Category

The 1918 Pandemic: Origin, pathology, and the virus itself

Sunday, July 1st, 2018Unanswered questions about the 1918 influenza pandemic: origin, pathology, and the virus itself

Oxford, John S et al.

The Lancet Infectious Diseases, 2018

- “…Studies of the resurrected 1918 virus showed it to be somewhat more virulent than contemporary H1N1 epidemic viruses in animal models, but not enough to be the sole factor in the high mortality rates…..”

- “…A cytokine storm, together with previous immune history, were important factors in explaining both enhanced pathology and protection from death….”

CDC Pandemic Flu Fighters

Thursday, June 28th, 2018Influenza poses one of the world’s greatest infectious disease challenges. The 1918 flu pandemic is a stark reminder of the devastation that can result from a global flu pandemic. CDC and its public health partners around the world work diligently to monitor and prepare for the next flu pandemic. Highlighted below are some of CDC’s flu fighters, dedicated public health professionals contributing to pandemic flu prevention and response at home and around the world.

Amra Uzicanin, MD, MPH, Team Lead, CDC’s Community Interventions for Infection Control Unit

As Lead of CDC’s Community Interventions for Infection Control Unit (CI-ICU), Dr. Amra Uzicanin is dedicated to developing the scientific evidence base and policies for use of nonpharmaceutical interventions (NPIs), for infectious disease control in community settings with a focus on pandemic flu. NPIs, also known as community mitigation measures, are the first line of defense to help slow the spread of pandemic influenza (flu). NPIs are readily available everywhere and can be used before a pandemic vaccine is available. CI-ICU works hard to prevent and reduce the spread of infectious diseases in communities by empowering people and communities to take action grounded in evidence-based knowledge of NPIs. Dr. Uzicanin says the 1918 flu pandemic “was a pandemic where ordinary people and communities as well as government authorities, public health officials, and healthcare professionals were striving to find new ways to fight off the flu and prevent its impact worldwide.”

Anita Patel, PharmD, MS, Team Lead, CDC’s Pandemic Medical Care and Countermeasures

Dr. Anita Patel is one of CDC’s key problem solvers working to protect the United States from a future influenza pandemic. Her responsibilities include making sure the nation has strategies in place for medical countermeasures to be able to treat sick patients and protect health care workers. Dr. Patel says the 1918 flu pandemic is a sobering reminder of the dangers of flu. “Learning from history allows us to plan for the possible range of impacts, and move the needle in preparedness.”

Anne Schuchat, MD (RADM, USPHS) CDC Principal Deputy Director

Principal Deputy Director of CDC, Dr. Anne Schuchat, is one of the many veterans of CDC’s fight on flu. Combatting influenza is a hallmark of Dr. Schuchat’s 30 years at CDC. In reflecting on the 1918 influenza pandemic, Dr. Schuchat says studying what happened can help us to better prepare the nation and the world for similar scenarios in the future.

Daniel Jernigan, MD, MPH (CAPT, USPHS), Director, Influenza Division

Dr. Dan Jernigan, a captain in the United States Public Health Service (USPHS), serves as director of the Influenza Division in CDC’s National Center for Immunization and Respiratory Diseases. In this role, Jernigan is always working to prepare for the next influenza pandemic. “We are determined to intervene where we can to stop the spread of disease—that’s public health,” he says. For CDC’s Influenza Division, stopping the spread of disease means, “tracking influenza viruses and human illness with influenza viruses worldwide – be it from seasonal, avian, swine, or other novel flu viruses. We track illness, study the virus, assess the risk posed by the virus, make vaccine viruses that are then used to manufacture flu vaccines and help make policies for influenza prevention and treatment.”

James Stevens, Ph.D., Associate Director, Laboratory Sciences in CDC’s Influenza Division

CDC’s influenza laboratories play a leading role in the ongoing global task of looking for new flu viruses, assessing the risk they pose to people, and supporting efforts to proactively prepare for the emergence of flu viruses considered to have pandemic potential. This includes everything from conducting surveillance on novel influenza viruses, to developing the viruses that are used to mass-produce flu vaccines, which are called “candidate vaccine viruses” or “CVVs”. As Associate Director for Laboratory Sciences in CDC’s Influenza Division, Dr. James Stevens oversees and coordinates CDC’s influenza laboratory operations. He says the 1918 flu pandemic “is the deadliest we’ve seen in modern times. We have to remember it because it is the worst-case scenario situation, and we don’t want it to happen again.”

Lisa Koonin, DrPH, MN, MPH, Deputy Director, Influenza Coordination Unit

Martin Cetron, MD, Director, Division of Global Migration and Quarantine (DGMQ)

Air travel today can easily facilitate the spread of diseases around the world with each flight. CDC’s Division of Global Migration and Quarantine (DGMQ) helps protect the health of our communities in a globally mobile world. As director of DGMQ, Dr. Martin (Marty) Cetron is a leader in global health and migration with a focus on emerging infections, tropical diseases, and vaccine-preventable diseases in mobile populations. He says the 1918 influenza (flu) pandemic was “monumental, and as an unprecedented event in human history, it taught us some really important lessons.

Stephen Redd, MD (RADM, USPHS) Director, Office of Public Health Preparedness and Response

CDC’s Dr. Stephen Redd has deep and diverse experiences in responding to public health emergencies, including the 2009 H1N1 influenza pandemic during which he served as incident commander for the CDC’s response. For the past four years, Dr. Redd has directed CDC’s Office of Public Health Preparedness and Response, the group responsible for ensuring CDC is prepared to respond to a public health emergency.

Terrence Tumpey, Ph.D., Chief, Influenza Immunology and Pathogenesis Branch

Dr. Terrence Tumpey is a microbiologist and chief of the Immunology and Pathogenesis Branch (IPB) in the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s Influenza Division. He’s perhaps best known for his groundbreaking work reconstructing the 1918 pandemic influenza virus. In 1918, this virus was responsible for the pandemic that is estimated to have killed at least 50 million people worldwide. In 2004, Dr. Tumpey was the first to physically reconstruct, or “rescue” the 1918 virus, using reverse genetics to build an H1N1 virus with all the same genes as the pandemic virus. After the reconstruction was completed, Dr. Tumpey was the first person to study the live 1918 H1N1 virus in the laboratory.

How does the media cover epidemics?

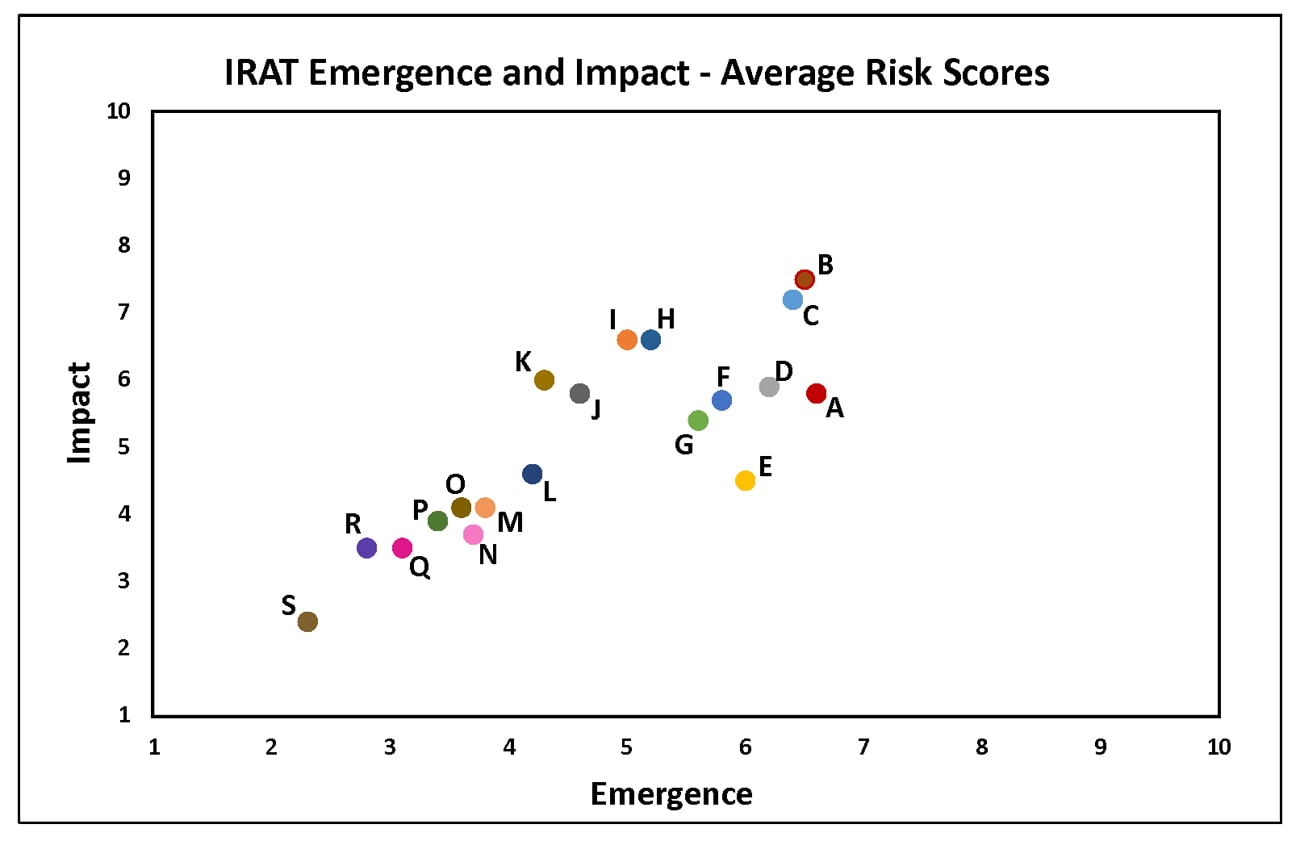

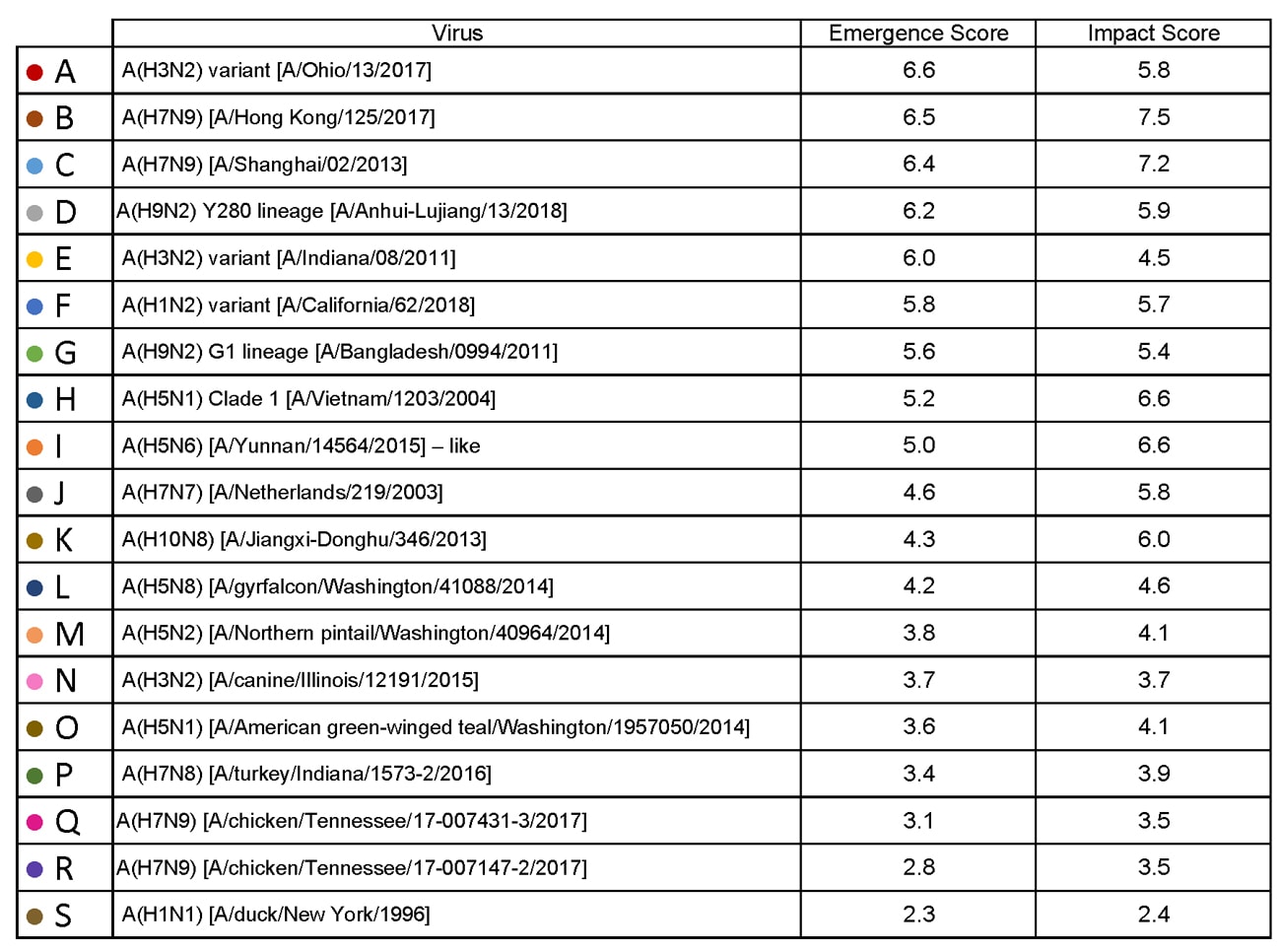

Friday, June 22nd, 2018Summary of Influenza Risk Assessment Tool (IRAT) Results: 2018

Tuesday, June 5th, 2018The Influenza Risk Assessment Tool (IRAT) is an evaluation tool conceived by CDC and further developed with assistance from global animal and human health influenza experts. The IRAT is used to assess the potential pandemic risk posed by influenza A viruses that are not currently circulating in people. Input is provided by U.S. government animal and human health influenza experts. Information about the IRAT is available at Influenza Risk Assessment Tool (IRAT) Questions and Answers(https://www.cdc.gov/flu/pandemic-resources/national-strategy/risk-assessment.htm).

| Virus | Most Recent Date Evaluated | Potential Emergence Risk(https://www.cdc.gov/flu/pandemic-resources/tools/risk-assessment.htm#emergence-risk) | Potential Impact Risk(https://www.cdc.gov/flu/pandemic-resources/tools/risk-assessment.htm#impact-risk) | Overall Summary |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| H1N1 [A/duck/New York/1996] | Nov 2011 | 2.3 | 2.4 | Low |

| H3N2 variant [A/Indiana/08/2011] | Dec 2012 | 6.0 | 4.5 | Moderate |

| H3N2 [A/canine/Illinois/12191/2015] | June 2016 | 3.7 | 3.7 | Low |

| H5N1 Clade 1 [A/Vietnam/1203/2004] | Nov 2011 | 5.2 | 6.6 | Moderate |

| H5N1 [A/American green-winged teal/Washington/1957050/2014] | Mar 2015 | 3.6 | 4.1 | Low-Moderate |

| H5N2 [A/Northern pintail/Washington/40964/2014] | Mar 2015 | 3.8 | 4.1 | Low-Moderate |

| H5N6 [A/Yunnan/14564/2015] – like | Apr 2016 | 5.0 | 6.6 | Moderate |

| H5N8 [A/gyrfalcon/Washington/41088/2014] | Mar 2015 | 4.2 | 4.6 | Low-Moderate |

| H7N7 [A/Netherlands/219/2003] | Jun 2012 | 4.6 | 5.8 | Moderate |

| H7N8 [A/turkey/Indiana/1573-2/2016] | July 2017 | 3.4 | 3.9 | Low |

| H7N9 [A/chicken/Tennessee/17-007431-3/2017] | Oct 2017 | 3.1 | 3.5 | Low |

| H7N9 [A/ chicken/Tennessee /17-007147-2/2017] | Oct 2017 | 2.8 | 3.5 | Low |

| H7N9 [A/Hong Kong/125/2017] | May 2017 | 6.5 | 7.5 | Moderate-High |

| H7N9 [A/Shanghai/02/2013] | Apr 2016 | 6.4 | 7.2 | Moderate-High |

| H9N2 G1 lineage [A/Bangladesh/0994/2011] | Feb 2014 | 5.6 | 5.4 | Moderate |

| H10N8 [A/Jiangxi-Donghu/346/2013] | Feb 2014 | 4.3 | 6.0 | Moderate |

H1N1: [North American avian H1N1 [A/duck/New York/1996]

Avian influenza A viruses are designated as highly pathogenic avian influenza (HPAI) or low pathogenic avian influenza (LPAI) based on molecular characteristics of the virus and the ability of the virus to cause disease and death in chickens in a laboratory setting. North American avian H1N1 [A/duck/New York/1996] is a LPAI virus and in the context of the IRAT serves as an example of a low risk virus.

Summary: The summary average risk score for the virus to achieve sustained human-to-human transmission was in the low risk category (less than 3). Similarly the average risk score for the virus to significantly impact public health if it were to achieve sustained human-to-human transmission also falls into the low risk range (less than 3).

H3N2 Variant:[A/Indiana/08/11]

Swine-origin flu viruses do not normally infect humans. However, sporadic human infections with swine-origin influenza viruses have occurred. When this happens, these viruses are called “variant viruses.” Influenza A H3N2 variant viruses (also known as “H3N2v” viruses) with the matrix (M) gene from the 2009 H1N1 pandemic virus were first detected in people in July 2011. The viruses were first identified in U.S. pigs in 2010. In 2011, 12 cases of H3N2v infection were detected in the United States. In 2012, 309 cases of H3N2v infection across 12 states were detected. The latest risk assessment for this virus was conducted in December 2012 and incorporated data regarding population immunity that was lacking a year earlier.

Summary: The summary average risk score for the virus to achieve sustained human-to-human transmission was in the moderate risk category (less than 6). The summary average risk score for the virus to significantly impact public health if it were to achieve sustained human-to-human transmission was in the low-moderate risk category (less than 5).

H3N2: [A/canine/Illinois/12191/2015]

The H3N2 canine influenza virus is an avian flu virus that adapted to infect dogs. This virus is different from human seasonal H3N2 viruses. Canine influenza A H3N2 virus was first detected in dogs in South Korea in 2007 and has since been reported in China and Thailand. It was first detected in dogs in the United States in April 2015(https://www.cdc.gov/flu/news/canine-influenza-update.htm). H3N2 canine influenza has reportedly infected some cats as well as dogs. There have been no reports of human cases.

Summary: The average summary risk score for the virus to achieve sustained human-to-human transmission was low risk (less than 4). The average summary risk score for the virus to significantly impact public health if it were to achieve sustained human-to-human transmission was in the low risk range (less than 4). For a full report, click here[186 KB, 4 pages](https://www.cdc.gov/flu/pandemic-resources/pdf/cdc-irat-virus-canine-h3n2.pdf).

H5N1 clade 1: [A/Vietnam/1203/2004]

The first human cases of highly pathogenic avian influenza (HPAI) H5N1 virus were reported from Hong Kong in 1997. Since 2003, highly pathogenic H5N1 avian influenza viruses have caused over 850 laboratory-confirmed human cases; mortality among these cases was high. A risk assessment of this H5N1 clade 1 virus was conducted in 2011 soon after the IRAT was first developed and when 12 hemagglutinin (HA) clades were officially recognized.

Summary: The summary average risk score for the virus to achieve sustained human-to-human transmission was in the moderate risk category (less than 6). The summary average risk score for the virus to significantly impact public health if it were to achieve sustained human-to-human transmission was in the high-moderate risk category (less than 7).

H5N1: [A/American green winged teal/Washington/1957050/2014]

In December 2014, an H5N1 highly pathogenic avian influenza virus was first isolated from an American green-winged teal in the state of Washington. This virus is a recombinant virus containing four genes of Eurasian lineage (PB2, HA, NP and M) and four genes of North American lineage (PB1, PA, NA and NS).In February 2015, the Canadian government reported isolating this virus from a backyard flock in the Fraser Valley. When this risk assessment was conducted in 2015, these were the only reported isolations of this virus. There have been no reports of human cases.

Summary: The summary average risk score for the virus to achieve sustained human-to-human transmission was in the low risk category (less than 4). The summary average risk score for the virus to significantly impact public health if it were to achieve sustained human-to-human transmission was in the low-moderate risk category (less than 5).

H5N2: [A/Northern pintail/Washington/40964/2014]

In December 2014, an H5N2 highly pathogenic avian influenza virus was first reported by the Canadian government from commercial poultry in the Fraser Valley.Subsequently this virus was isolated from wild birds, captive wild birds, backyard flocks and commercial flocks in the United States.This virus is a recombinant virus composed of five Eurasian lineage (PB2, PA, HA, M and NS) genes and three North American lineage (PB1, NP and NA) genes. There have been no reports of human cases.

Summary: The average summary risk score for the virus to achieve sustained human-to-human transmission was low risk (less than 4).The average summary risk score for the virus to significantly impact public health if it were to achieve sustained human-to-human transmission was in the low-moderate risk range (less than 5).

H5N6: [A/Yunnan/14564/2015 (H5N6-like)]

Between January 2014 and March 2016, there have been 10 human cases of H5N6 highly pathogenic avian influenza reported. Nine reportedly experienced severe disease and six died. Avian outbreaks of this virus were first reported from China in 2013. Subsequently avian outbreaks have been reported in at least three countries (China, Vietnam and Lao PDR) through 2015.

Summary: The summary average risk score for the virus to achieve sustained human-to-human transmission was in the moderate range (less than 6).The average summary risk score for the virus to significantly impact on public health if it were to achieve sustained human-to-human transmission fell in the moderate range (less than 7).

H5N8: [A/gyrfalcon/Washington/41088/2014]

In December 2014, an H5N8 highly pathogenic avian influenza virus was first isolated from a sample collected in the United States from a captive gyrfalcon.Subsequently this virus was isolated from wild birds, captive wild birds, backyard flocks and commercial flocks in the United States.This virus (clade 2.3.4.4) is similar to Eurasian lineage H5N8 viruses that have been isolated in South Korea, China, Japan, the Netherlands, the United Kingdom and Germany in late 2014-early 2015.There have been no reports of human cases.

Summary: The average risk score for the virus to achieve sustained human-to-human transmission was in the low-moderate range< (less than 5). The average summary risk score for the virus to significantly impact public health if it were to achieve sustained human-to-human transmission fell in the low-moderate range (less than 5).

In 2003 the Netherlands reported highly pathogenic avian influenza (HPAI) in approximately 255 commercial flocks.Coinciding with human activities around these infected flocks, 89 human cases of H7N7 were identified.Cases primarily reported conjunctivitis, although a few also reported mild influenza-like illness.There was one death.

Summary: The summary average risk score for this virus to achieve sustained human-to-human transmission was in the low-moderate risk range (less than 5). The summary average risk score for this virus to significantly impact the public’s health if it were to achieve sustained human-to-human transmission fell in the moderate risk range (less than 7).

H7N8: [A/turkey/Indiana/1573-2/2016]

In January 2016, a highly pathogenic avian influenza (HPAI) virus of North American lineage was identified in a turkey flock in Indiana. Putative low pathogenic avian influenza (LPAI) viruses similar to A/turkey/Indiana/1573-2/2016 were subsequently isolated from 9 other turkey flocks in the area. There were no reports of human cases associated with this virus at the time of the IRAT scoring.

Summary: A risk assessment of this LPAI virus was conducted in July 2017. The overall IRAT risk assessment score for this virus falls into the low risk category (< 4). The summary average risk score for the virus to achieve sustained human-to-human transmission is in the low risk category (3.4). The summary average risk score for the virus to significantly impact public health if it were to achieve sustained human-to-human transmission was also in the low risk category (3.9).

Low pathogenic avian influenza (LPAI) H7N9 viruses were first reported from China in March 2013. These viruses were first scored using the IRAT in April 2013, and then annually in 2014, 2015, and 2016 with no change in overall risk scores. Between October 2016 and May 2017 evidence of two divergent lineages of these viruses was detected – the Pearl River Delta lineage and the Yangtze River Delta lineage. The IRAT was used to assess LPAI H7N9 [A/Hong Kong/125/2017], a representative of the Yangtze River Delta viruses.

Summary: A risk assessment of H7N9 [A/Hong Kong/125/2017] was conducted in May 2017. The overall IRAT risk assessment score for this virus falls into the moderate-high risk category and is similar to the scores for the previous H7N9 viruses. The summary average risk score for the virus to achieve sustained human-to-human transmission is in the moderate risk category (less than 7). The summary average risk score for the virus to significantly impact public health if it were to achieve sustained human-to-human transmission was in the moderate-high risk category (less than 8).

H7N9: Avian H7N9 [A/Shanghai/02/2013]

On 31 March 2013, the China Health and Family Planning Commission notified the World Health Organization (WHO) of three cases of human infection with influenza H7N9. As of August 2016, the WHO has received reports of 821 cases, 305 have died. This low pathogenic avian influenza virus was rescored most recently in April 2016 with no substantive change in risk scores since May 2013.

Summary: The summary average risk score for the virus to achieve sustained human-to-human transmission was in the moderate risk category (less than 7). The average risk score for the virus to significantly impact public health if it were to achieve sustained human-to-human transmission fell in the high-moderate risk range (less than 8).

H7N9: Low Pathogenic North American avian [A/chicken/Tennessee/17-007431-3/2017]

Surveillance conducted in March 2017 during the investigation of a highly pathogenic avian influenza (HPAI) A(H7N9) virus in commercial poultry in Tennessee revealed the contemporaneous presence of North American lineage low pathogenic avian influenza (LPAI) A(H7N9) virus in commercial and backyard poultry flocks in Tennessee and three other states. The outbreak in poultry appeared limited with no further detections in subsequent surveillance. There were no reports of human cases associated with this virus.

Summary: A risk assessment this North American lineage LPAI A(H7N9) virus was conducted in October 2017. The overall IRAT risk assessment score for this virus falls into the low risk category (< 4). The summary average risk score for the virus to achieve sustained human-to-human transmission was in the low risk category (score 3.1). The average risk score for the virus to significantly impact public health if it were to achieve sustained human-to-human transmission was between the low to low-moderate range (score 3.5). For a full report, click here[228 KB, 4 pages](https://www.cdc.gov/flu/pandemic-resources/pdf/cdc-irat-virus-lpai.pdf).

H7N9: High Pathogenic North American avian [A/chicken/Tennessee/17-007147-2/2017]

In March 2017, the U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) reported the detection of a highly pathogenic avian influenza (HPAI) A(H7N9) virus in 2 commercial poultry flocks in Tennessee. Full genome sequence analysis indicated that all eight gene segments of the virus were of North American wild bird lineage and genetically distinct from the lineage of influenza A(H7N9) viruses infecting poultry and humans in China since 2013. The outbreak investigation revealed that a related North American low pathogenic avian influenza A(H7N9) was circulating in poultry prior to the detection of the HPAI A(H7N9). There were no reports of human cases associated with this virus.

Summary: A risk assessment this North American lineage HPAI A(H7N9) virus was conducted in October 2017. The overall IRAT risk assessment score for this virus falls into the low risk category (< 4). The summary average risk score for the virus to achieve sustained human-to-human transmission is in the low risk category (2.8). The summary average risk score for the virus to significantly impact public health if it were to achieve sustained human-to-human transmission was also in the low risk category (3.5). For a full report, click here[225 KB, 4 pages](https://www.cdc.gov/flu/pandemic-resources/pdf/cdc-irat-virus-hpai.pdf).

H9N2: Avian H9N2 G1 lineage [A/Bangladesh/0994/2011]

Human infections with influenza AH9N2 virus have been reported sporadically, cases reportedly exhibited mild influenza-like illness. Historically these low pathogenic avian influenza viruses have been isolated from wild and domestic birds. In response to these reports, a risk assessment of this H9N2 influenza virus was conducted in 2014.

Summary: The summary average risk score for the virus to achieve sustained human-to-human transmission was in the moderate risk category (less than 6). The summary average risk score for the virus to significantly impact public health if it were to achieve sustained human-to-human transmission also fell in the moderate risk range (less than 6).

H10N8: Avian H10N8 [A/Jiangxi-Donghu/346/2013]

Two human infections with influenza A(H10N8) virus were reported by the China Health and Family Planning Commission in 2013 and 2014 (one each year). Both cases were hospitalized and one died. Historically low pathogenic avian influenza H10 and N8 viruses have been recovered from birds. A risk assessment of the H10N8 influenza was conducted in 2014.

Summary: The summary average risk score for the virus to achieve sustained human-to-human transmission was low-moderate (less than 5). The average risk score for the virus to significantly impact public health if it were to achieve sustained human-to-human transmission was in the moderate risk range (less than 7).

Take-aways from the CDC-Emory University symposium about influenza pandemics that marked the 100th anniversary of the 1918 Influenza Pandemic

Tuesday, May 8th, 2018- “The more I learn about flu, the less I know,” said Michael Osterholm PhD, MPH, director of the University of Minnesota’s Center for Infectious Disease Research and Policy

- More people will die from the non-pandemic aspects of such a global health crisis.

- The US economy is so inextricably linked to other countries, especially China’s, that a pandemic would paralyze supply chains for both consumer and medical goods.

- A pandemic would bring “unprecedented employee absenteeism,” Osterholm said.

- Consider that 30 of the most common generic medicines currently used in the United States are wholly or partially manufactured in China. “Look at what happened with saline bags in Puerto Rico,” said Osterholm.

- Arnold Monto, MD, from the University of Michigan: Modern tools, including the flu vaccine, would mean it’s unlikely the 1918 pandemic could ever be repeated.

- Luciana Borio, MD, of the White House National Security Council, confirmed that China is not currently sharing flu vaccine strain information nor any progress made on its development of a universal flu vaccine.

- Trust for America’s Health (TFAH’s) annual readiness report, “Ready or Not?” : TFAH President and CEO John Auerbach, MBA, said no states were completely prepared for a pandemic (based on 11 criteria, and ranked from 1 to 10). Only five states had a preparedness ranking of 8 or 9, and half sat at a 5 or lower. The report was published in December.

- Dwindling public health department budgets are a problem

- Nancy Messonnier, MD, head of CDC’s National Center for Immunization and Respiratory Diseases, said that despite gaps in preparedness, the CDC is better equipped to handle a flu pandemic now than it was in 2009, when a novel H1N1 flu strain first emerged. Technologies, including mobile apps that help consumers find flu shots, and antivirals are putting the power to prevent and fight flu into patients’ hands.

US experts sound off: The USA ‘….is “woefully unprepared for these biological threats” in an increasingly interdependent world……’

Monday, April 30th, 2018- James Lawler is “…a retired Navy commander whose experience includes serving as director for medical preparedness policy on the National Security Council and director for biodefense policy on the White House’s Homeland Security Council…”

- “….Kenneth Luongo, president and founder of the Partnership for Global Security, echoed that the U.S. “remains woefully underprepared” for a biological attack or a “new intensity level” of pathogens…..”

- “….Former USAID Director Andrew Natsios, director of the Scowcroft Institute of International Affairs, told the panel that the country is “a lot more fragile than we realize” when it comes to emergency response….”

A United States-FAO partnership working to strengthen the capacity of developing countries to manage outbreaks of diseases in farm animals has in just 12 months succeeded in training over 4,700 veterinary health professionals in 25 countries in Africa, Asia and the Middle East.

Wednesday, March 14th, 2018March 2018, Rome – A United States-FAO partnership working to strengthen the capacity of developing countries to manage outbreaks of diseases in farm animals has in just 12 months succeeded in training over 4,700 veterinary health professionals in 25 countries in Africa, Asia and the Middle East.

The FAO-provided technical trainings covered a gamut of key competencies, including disease surveillance and forecasting, laboratory operations, biosafety and biosecurity, prevention and control methods and outbreak response strategies.

All told, 3,266 vets in Asia, 619 in West Africa, 459 in East Africa, and 363 in the Middle East benefitted. They are on the front line of the effort to stop new diseases at their source. (Full list below)

“Over the course of this relationship we’ve learned that there are many mutually beneficial areas of interest between the food and agricultural community and the human health community,” said Dennis Carroll, Director of USAID’s Global Health Security and Development Unit.

“A partnership with FAO not only enables us to protect human populations from future viral threats, but also to protect animal populations from viruses that could decimate food supplies. It’s not just a global health, infectious disease issue, but also a food security, food safety, and economic growth issue,” Carroll added.

“Some 75 percent of new infectious diseases that have emerged in recent decades originated in animals before jumping to us Homo sapiens, a terrestrial mammal. This is why improving adequately discovering and tackling animal disease threats at source represents a strategic high-ground in pre-empting future pandemics,” said Juan Lubroth, FAO Chief Veterinary Officer

“A proactive approach is absolutely critical, and for that, the world needs well-trained, up-to-speed professionals — biologists, ecologists, microbiologists, modellers, physicians and veterinarians — which is why the United States’ consistent support for building up that kind of capacity has been invaluable,” Lubroth said.

Viral risks

Population growth, agricultural expansion and environmental encroachment, and the rise of inter-continental food supply chains in recent decades have dramatically altered how diseases emerge, jump species boundaries, and spread, FAO studies have shown.

A new study just published by USAID’s Dennis Carroll and experts from several institutions including FAO suggests that just 0.01 percent of the viruses behind zoonotic disease outbreaks are known to science. The authors have proposed an international partnership, The Global Virome Project, aimed at characterizing the most risky of these. Doing so would allow more proactive responses to disease threats, with benefits not only for public health but also for the livelihoods of poor, livestock-depending farming communities.

Partnering for global health security

The close FAO-USAID partnership on animal health goes back over a decade.

Experts from the two organizations are meeting in Rome this week to review progress achieved in the past year and how to respond to threats like species-jumping zoonotic illnesses and the growing trends of antimicrobial resistance and options for intervention measures in food production and protection of public health.

In addition to trainings, via the USAID- Emerging Pandemic Threats (EPT) programme, FAO conducts research and advises on policy in order to help countries increase their resilience to disease emergence and protect animal and human health.

And to enable rapid responses by governments to disease events FAO has leveraged USAID support to work with the United Nations Humanitarian Response Depots to establish a series of emergency equipment and gear stockpiles in 15 countries that facilitate rapid and adequate responses to outbreaks.

FAO is also key player and advisor to the Global Health Security Agenda (GHSA), a growing partnership of over 60 countries, NGOs and international organizations working to improve early detection of and responses to infectious disease threats. USAID support under the GHSA umbrella is helping FAO engage with 17 countries in Africa and Asia to strengthen capabilities to detect and respond to zoonotic diseases.

Thanks to USAID support for the EPT and GSHA, FAO is actively tackling disease issues and building national capacities in over 30 countries

Economic impacts as well as health consequences

Beyond the risks posed to human health, animal diseases can cost billions of dollars and hamstringing economic growth.

The most damaging outbreaks of high impact disease in recent decades all had an animal source, including H5N1 highly pathogenic avian influenza, H1N1 pandemic influenza, Ebola, severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS) and Middle East Respiratory Syndrome (MERS).

For example, the H5N1 outbreak of the mid-2000s caused an estimated $30 billion in economic losses, globally; a few years later, H1N1 racked up as much as $55 billion in damages.

Not to mention that for millions of the world’s poorest people, animals are their primary capital assets — “equity on four legs”. Losing them can push these families out of self-reliance and into destitution.

Note to editors. The countries where the trainings took place were: Bangladesh, Burkina Faso, Cambodia, Cameroon, China, Democratic Republic of the Congo, Egypt, Ghana, Guinea, Indonesia, Jordan, Kenya, Laos People’s Democratic Republic , Liberia, Mali, Myanmar, Nepal, Senegal, Sierra Leone, United Republic of Tanzania, Uganda and Viet Nam.

Pandemic planning: Ethical epidemic response

Monday, March 12th, 2018Flu season and pandemic planning: Ethical epidemic response

Triage and ethical considerations in prioritizing care for healthcare professionals and the public in an influenza pandemic

Feb 28, 2018

By Jeffery A. King, faculty, American Military University

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention recently signaled that the 2017-2018 flu season is expected to meet the criteria for a “high severity” epidemic. At the end of January, there were more than 83,000 reported cases of flu with heightened mortality. This year’s viruses are beginning to overwhelm healthcare providers around the country. The challenge of caring for so many is only compounded by shortages of rapid influenza diagnostic tests, Tamiflu, IV bags, and even bed space in many hospitals.

Trials like this can force public health officials and healthcare providers into the unenviable position of making impulsive and impactful decisions during unprecedented situations. As with so many other public safety initiatives, these decisions can test American ethics by pitting individual liberties and other shared values against approaches that are hard to swallow but often necessary to achieve a greater good. Here are a few ethical challenges to consider for current and future pandemic planning.

Ethical challenges: how to prioritize care?

One of the more difficult challenges that can arise for public health and healthcare decision-makers is the task of prioritizing care among otherwise equally affected patients. It is worth pointing out that during an epidemic, patients cannot always be directed to other facilities, and medicine and equipment cannot always be borrowed or redistributed because multiple regions are suffering from similar shortages.

Determining how patients are prioritized and how treatment is managed when there simply are not enough personnel, beds, equipment or medicine is a morally unpleasant choice. Providers can either treat patients on a first-come, first-served basis, which could leave scores without appropriate healthcare, or they can triage patients based on factors like the relative acuteness of their illness, overall health, age and other characteristics.

Triage during a resource-constrained epidemic might exclude many of those who are too sick or who would require overly intensive care, thus allowing concentrated effort on those most likely to recover. Beyond the deathly ill, what other factors might the public consider justifiable toward accomplishing the greater good? Is it only acceptable under epidemic conditions to deny treatment to complex cases, such as those with other acute or chronic health conditions, the disabled or the elderly? If the elderly are to be denied treatment, at what age would the limit be set? What about an elderly physician or nurse who may be able to assist in the response if she can recover?

All of these decisions require consequentialist thinking – an attempt to justify decisions by their expected outcomes. The difficulty with a consequentialist approach is that decisions can easily slide into the arbitrary depending on context, variables, and the decision-maker’s subjective appraisal of the outcomes. Decision-makers are rarely able to foresee the full consequences and the law of unintended consequences will almost certainly introduce suspicion into any well-intended triage and treatment plan. In order to achieve agreement on the just and equitable provision of healthcare during an epidemic, the process and procedures for decision-making should be publicly and openly debated well before an epidemic ever occurs.

Prioritizing healthcare workers

In a 2014 case study on ethical decision-making during catastrophic pandemics, Dr. Linda Kiltz advocates strongly for the prioritization and protection of healthcare providers. Influenza and other viruses are not discriminatory in their transmission; like water, viruses follow a path of least resistance. As the most seriously affected patients make their way to healthcare facilities, the employees at those facilities are in the direct path of the virus.

Medical professionals who are obligated or willing to expose themselves directly to a viral epidemic should receive prioritized care if they contract the virus. They are accepting risk to their own health, and communities owe them a certain respect and reciprocity for that sacrifice. In short, where healthcare workers have a duty to care for the community, the community has a reciprocal duty to support them.

Communities must, for example, ensure that healthcare workers have access to the appropriate training and personal protective equipment to perform their jobs competently and safely. Communities must also ensure that healthcare workers’ personal and family needs, like child and elder care, meals, and even mental and spiritual care, are supported.

Beyond reciprocity, protecting and supporting healthcare providers during an epidemic serves a distinctly utilitarian purpose. It is easily agreed that healthcare providers are one of the most valuable resources during an epidemic. These professionals represent a valuable, limited human resource, so protecting their health and supporting their personal needs can help to ensure their continued availability for response.

Protecting the public

Protecting the public by controlling the spread of viruses is another priority during epidemics. Quarantine and isolation are common public health tools used to prevent or mitigate the effects of an epidemic. While these practices have long been authorized by law, officials still must appreciate the sensitivities and impacts, and plan for supporting those affected. Nowhere else is the struggle to balance public health priorities against individual liberties more palpable than it is with implementing preventative actions.

Restrictions on freedom of movement are, practically speaking, the most disruptive burdens for citizens placed in isolation or quarantine. Restricting a person’s movement means impairing their ability to support themselves and their families. It precludes and jeopardizes employment, prohibits attendance at school and church, and cuts families off from all manner of goods and services.

Beyond due process and mere fairness, citizens placed in isolation and quarantine also require support from the government and their communities. If citizens know that their needs will continue to be supported, and their employment and other opportunities protected, then restrictions on their liberty will be far less distressing and disagreeable.

Engagement and collaboration

An influenza epidemic like the one the U.S. is currently experiencing can present a significant threat to public health and overall domestic safety and security. Seeing the ethical challenges in decisions being made during a frenzied response should encourage communities to address the issues early. The more time a community has to fully discuss, negotiate, and agree on policies and plans that will guide action during response, the less distrust those actions will incur.

If the decision-making during an epidemic response appears arbitrary and unequitable, it can break down a community’s trust and motivation for compliance. In the end, collaboration between the government, the healthcare sector, and the broader community is necessary to create consensus on these ethically challenging matters.

About the Author

Jeff King is a retired Coast Guard judge advocate and a faculty member in the School of Security & Global Studies at American Military University, where he primarily teaches undergraduate and graduate courses in law and ethics. To contact him, email IPSauthor@apus.edu.

WHO: List of Blueprint priority diseases

Sunday, March 11th, 2018List of Blueprint priority diseases

2018 annual review of the Blueprint list of priority diseases

For the purposes of the R&D Blueprint, WHO has developed a special tool for determining which diseases and pathogens to prioritize for research and development in public health emergency contexts. This tool seeks to identify those diseases that pose a public health risk because of their epidemic potential and for which there are no, or insufficient, countermeasures. The diseases identified through this process are the focus of the work of R& D Blueprint. This is not an exhaustive list, nor does it indicate the most likely causes of the next epidemic.

The first list of prioritized diseases was released in December 2015.

Using a published prioritization methodology, the list was first reviewed in January 2017.

The second annual review occurred 6-7 February, 2018. Experts consider that given their potential to cause a public health emergency and the absence of efficacious drugs and/or vaccines, there is an urgent need for accelerated research and development for*:

- Crimean-Congo haemorrhagic fever (CCHF)

- Ebola virus disease and Marburg virus disease

- Lassa fever

- Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus (MERS-CoV) and Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome (SARS)

- Nipah and henipaviral diseases

- Rift Valley fever (RVF)

- Zika

- Disease X

Disease X represents the knowledge that a serious international epidemic could be caused by a pathogen currently unknown to cause human disease, and so the R&D Blueprint explicitly seeks to enable cross-cutting R&D preparedness that is also relevant for an unknown “Disease X” as far as possible.

A number of additional diseases were discussed and considered for inclusion in the priority list, including: Arenaviral hemorrhagic fevers other than Lassa Fever; Chikungunya; highly pathogenic coronaviral diseases other than MERS and SARS; emergent non-polio enteroviruses (including EV71, D68); and Severe Fever with Thrombocytopenia Syndrome (SFTS).

These diseases pose major public health risks and further research and development is needed, including surveillance and diagnostics. They should be watched carefully and considered again at the next annual review. Efforts in the interim to understand and mitigate them are encouraged.

Although not included on the list of diseases to be considered at the meeting, monkeypox and leptospirosis were discussed and experts stressed the risks they pose to public health. There was agreement on the need for: rapid evaluation of available potential countermeasures; the establishment of more comprehensive surveillance and diagnostics; and accelerated research and development and public health action.

Several diseases were determined to be outside of the current scope of the Blueprint: dengue, yellow fever, HIV/AIDs, tuberculosis, malaria, influenza causing severe human disease, smallpox, cholera, leishmaniasis, West Nile Virus and plague. These diseases continue to pose major public health problems and further research and development is needed through existing major disease control initiatives, extensive R&D pipelines, existing funding streams, or established regulatory pathways for improved interventions. In particular, experts recognized the need for improved diagnostics and vaccines for pneumonic plague and additional support for more effective therapeutics against leishmaniasis.

The experts also noted that:

- For many of the diseases discussed, as well as many other diseases with the potential to cause a public health emergency, there is a need for better diagnostics.

- Existing drugs and vaccines need further improvement for several of the diseases considered but not included in the priority list.

- Any type of pathogen could be prioritised under the Blueprint, not only viruses.

- Necessary research includes basic/fundamental and characterization research as well as epidemiological, entomological or multidisciplinary studies, or further elucidation of transmission routes, as well as social science research.

- There is a need to assess the value, where possible, of developing countermeasures for multiple diseases or for families of pathogens.

The impact of environmental issues on diseases with the potential to cause public health emergencies was discussed. This may need to be considered as part of future reviews.

The importance of the diseases discussed was considered for special populations, such as refugees, internally displaced populations, and victims of disasters.

The value of a One Health approach was stressed, including a parallel prioritization processes for animal health. Such an effort would support research and development to prevent and control animal diseases minimising spill-over and enhancing food security. The possible utility of animal vaccines for preventing public health emergencies was also noted.

Also there are concerted efforts to address anti-microbial resistance through specific international initiatives. The possibility was not excluded that, in the future, a resistant pathogen might emerge and appropriately be prioritized.

*The order of diseases on this list does not denote any ranking of priority.