Archive for February, 2016

A 5.8-magnitude earthquake struck New Zealand with such force, it caused part of a cliff to collapse.

Sunday, February 14th, 2016Afghanistan: At least 3,545 noncombatants died and another 7,457 were injured by fighting last year in a 4% increase over 2014.

Sunday, February 14th, 2016Evidence of Zika Virus Infection in Brain and Placental Tissues from Two Congenitally Infected Newborns and Two Fetal Losses — Brazil, 2015.

Sunday, February 14th, 2016Martines RB, Bhatnagar J, Keating MK, et al. Notes from the Field: Evidence of Zika Virus Infection in Brain and Placental Tissues from Two Congenitally Infected Newborns and Two Fetal Losses — Brazil, 2015. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2016;65(Early Release):1–2. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.15585/mmwr.mm6506e1er.

Early Release / February 10, 2016 / 65(06);1–2

Zika virus is a mosquito-borne flavivirus that is related to dengue virus and transmitted primarily by Aedes aegypti mosquitoes, with humans acting as the principal amplifying host during outbreaks. Zika virus was first reported in Brazil in May 2015 (1). By February 9, 2016, local transmission of infection had been reported in 26 countries or territories in the Americas.* Infection is usually asymptomatic, and, when symptoms are present, typically results in mild and self-limited illness with symptoms including fever, rash, arthralgia, and conjunctivitis. However, a surge in the number of children born with microcephaly was noted in regions of Brazil with a high prevalence of suspected Zika virus disease cases. More than 4,700 suspected cases of microcephaly were reported from mid-2015 through January 2016, although additional investigations might eventually result in a revised lower number (2). In response, the Brazil Ministry of Health established a task force to further investigate possible connections between the virus and brain anomalies in infants (3).

Since November 2015, CDC has been developing assays for Zika virus testing in formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded (FFPE) tissue samples. In December 2015, FFPE tissues samples from two newborns (born at 36 and 38 weeks gestation) with microcephaly who died within 20 hours of birth and two miscarriages (fetal losses at 11 and 13 weeks) were submitted to CDC, from the state of Rio Grande do Norte in Brazil, for histopathologic evaluation and laboratory testing for suspected Zika virus infection. All four mothers had clinical signs of Zika virus infection, including fever and rash, during the first trimester of pregnancy, but did not have clinical signs of active infection at the time of delivery or miscarriage. The mothers were not tested for antibodies to Zika virus. Samples included brain and other autopsy tissues from the two newborns, a placenta from one of the newborns, and products of conception from the two miscarriages.

FFPE tissues were tested by Zika virus reverse transcription-polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) targeting the nonstructural protein 5 and envelope genes using general methods for RT-PCR (4), and by immunohistochemistry using a mouse polyclonal anti-Zika virus antibody, using methods previously described (5). Specific specimens from all four cases were positive by RT-PCR, and sequence analysis provided further evidence of Zika virus infection, revealing highest identities with Zika virus strains isolated from Brazil during 2015. In the newborns, only brain tissue was positive by RT-PCR assays. Specimens from two of the four cases were positive by immunohistochemistry: viral antigen was noted in mononuclear cells (presumed to be glial cells and neurons within the brain) of one newborn, and within the chorionic villi from one of the miscarriages. Testing for dengue virus was negative by RT-PCR in specimens from all cases.

For both newborns, significant histopathologic changes were limited to the brain, and included parenchymal calcification, microglial nodules, gliosis, and cell degeneration and necrosis. Other autopsy tissues and placenta had no significant findings. Tests for toxoplasmosis, rubella, cytomegalovirus, herpes simplex, and HIV were negative in the two mothers who experienced miscarriages. Placental tissue from one miscarriage showed heterogeneous chorionic villi with calcification, fibrosis, perivillous fibrin deposition, and patchy intervillositis and focal villitis, while tissue from the other miscarriage had sparsely sampled normal-appearing chorionic villi.

This report describes evidence of a link between Zika virus infection and microcephaly and fetal demise through detection of viral RNA and antigens in brain tissues from infants with microcephaly and placental tissues from early miscarriages. Histopathologic findings indicate the presence of Zika virus in fetal tissues. These findings also suggest brain and early gestational placental tissue might be the preferred tissues for postmortem viral diagnosis. Nonfrozen, formalin-fixed specimens or FFPE blocks are the preferred sample type for histopathologic evaluation and immunohistochemistry, and RT-PCR can be performed on either fresh frozen or formalin-fixed specimens. To better understand the pathogenesis of Zika virus infection and associated congenital anomalies and fetal death, it is necessary to evaluate autopsy and placental tissues from additional cases, and to determine the effect of gestational age during maternal illness on fetal outcomes.

References

- Zanluca C, de Melo VC, Mosimann ALP, Dos Santos GI, Dos Santos CN, Luz K. First report of autochthonous transmission of Zika virus in Brazil. Mem Inst Oswaldo Cruz 2015;110:569–72. CrossRef PubMed

- Victoria CG, Schuler-Faccini L, Matijasevich A, Ribeiro E, Pessoa A, Barros FC. Microcephaly in Brazil: how to interpret reported numbers? Lancet 2016. Epub February 5, 2016. CrossRef

- Schuler-Faccini L, Ribeiro EM, Feitosa IML, et al. ; Brazilian Medical Genetics Society–Zika Embryopathy Task Force. Possible association between Zika virus infection and microcephaly—Brazil, 2015. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2016;65:59–62. CrossRef PubMed

- Bhatnagar J, Blau DM, Shieh WJ, et al. Molecular detection and typing of dengue viruses from archived tissues of fatal cases by rt-PCR and sequencing: diagnostic and epidemiologic implications. Am J Trop Med Hyg 2012;86:335–40. CrossRef PubMed

- Shieh WJ, Blau DM, Denison AM, et al. 2009 pandemic influenza A (H1N1): pathology and pathogenesis of 100 fatal cases in the United States. Am J Pathol 2010;177:166–75. CrossRef PubMed

* Updated information about local transmission of Zika virus is available online (http://www.cdc.gov/zika/geo/index.html).

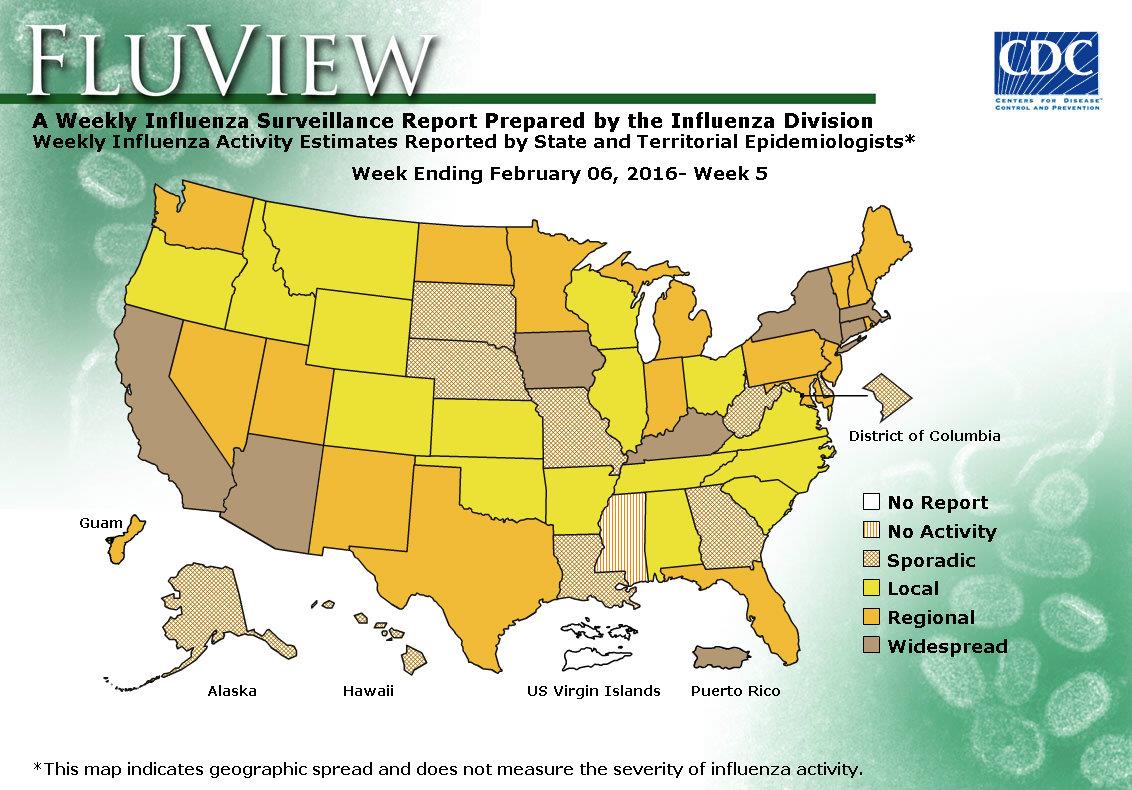

During week 5 (January 31-February 6, 2016), influenza activity increased slightly in the United States.

Sunday, February 14th, 2016

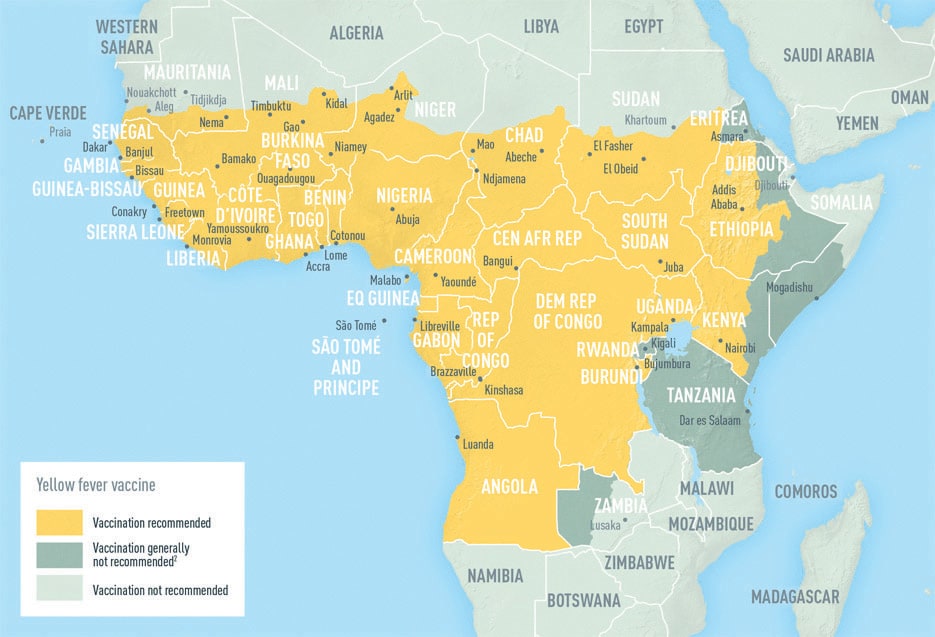

Yellow Fever: As of 8 February, a total of 164 suspected cases and 37 deaths had been reported in Angola

Sunday, February 14th, 2016

Yellow Fever – Angola

12 February 2016 – On 21 January 2016, the National IHR Focal Point of Angola notified WHO of an outbreak of yellow fever.

The first cases were identified in the district of Viana (Luanda province) on 5 December 2015. Yellow fever infection was initially confirmed in three patients by polymerase chain reaction at the Zoonosis and Emerging Disease Laboratory of the National Institute for Communicable Diseases in Johannesburg, South Africa and at the Pasteur Institute in Dakar, Senegal.

As of 8 February, a total of 164 suspected cases and 37 deaths had been reported in Angola. The majority of cases (n=138) had been reported in the province of Luanda. Other affected provinces include Cabinda, Cuanza Sul, Huambo, Huila and Uige. Suspected cases are undergoing laboratory testing in order to rule out other aetiologies and cross reactions with yellow fever.

“In the context of the Zika virus outbreak, Brazil, Colombia, El Salvador, Suriname and Venezuela have reported an increase of GBS (Guillain-Barre Syndrome),” the WHO said in a weekly report.

Saturday, February 13th, 2016- WHO has called for a coordinated and multisectoral response through an inter-agency Strategic Response Framework focusing on response, surveillance and research.

- 39 countries have reported locally acquired circulation of the virus since January 2007. Geographical distribution of the virus has steadily expanded.

- Six countries (Brazil, French Polynesia, El Salvador, Venezuela, Colombia and Suriname) have reported an increase in the incidence of cases of microcephaly and/or Guillain-Barré syndrome (GBS) in conjunction with an outbreak of the Zika virus. Puerto Rico and Martinique have reported cases of GBS associated with Zika virus infection without an increase of incidence. No scientific evidence to date confirms a link between Zika virus and microcephaly or GBS.

- Women’s reproductive health has been thrust into the limelight with the spread of the Zika virus. The latest evidence suggests that Zika virus infection during pregnancy may be linked to microcephaly in newborn babies.

- WHO advice on travel to Zika-affected countries includes advice for pregnant women as well as women who are trying to become pregnant and their sexual partners.

Taiwan: 114 bodies recovered from the rubble of a high-rise apartment building that collapsed in an earthquake in Tainan, leaving only one missing

Saturday, February 13th, 2016Venezuela and Colombia in late January and early February notified the WHO of increases in Guillain-Barre Syndrome cases. Zika Virus?

Saturday, February 13th, 2016Guillain-Barré syndrome – Colombia and Venezuela

Between 30 January and 2 February 2016, the National IHR Focal Points of Colombia and Venezuela informed PAHO/WHO of increases in the number of Guillain-Barre Syndrome (GBS) cases recorded at the national level.

Colombia

From epidemiological week (EW) 51 of 2015 to EW 3 of 2016, 86 GBS cases were reported. On average, Colombia registers 242 GBS cases per year or approximately 19 cases per month or 5 cases per week. The 86 GBS cases reported in those 5 weeks is three times higher than the averaged expected cases of the 6 previous years.

Initial reports indicated that all the 86 reported GBS cases presented with symptoms compatible with a Zika virus infection. Of the 58 cases for which information is available, 57% were male and 94.8% were 18 years old or older.

Venezuela

From 1 January to 31 January 2016, 252 GBS cases with a spatiotemporal association to Zika virus were reported. While cases were recorded in the majority of the federal territories of the country, 66 were detected in the state of Zulia, mainly in the Maracaibo municipality.

Preliminary analysis of the GBS cases in the state of Zulia indicates that the 66 cases originated from six municipalities. Of the 66 cases, 30% were 45 to 54 years old and 29% were 65 years or older; 61% were male and 39% were female. A clinical history consistent with Zika virus infection was observed in the days prior to onset of neurological symptoms in 76% of the GBS cases in the state of Zulia. Associated comorbidities were present in 65% of the cases. Patients were treated with plasmapheresis and/or immunoglobulin. In some cases, according to medical indication, both treatments were used following the treatment protocol established by the Ministry of Popular Power for Health.

Zika virus infection was confirmed by polymerase chain reaction in three GBS cases, including a fatal case with no comorbidities. A total of three cases presenting with other neurological disorders were also biologically confirmed.

Between late November to 28 January 2016, 192 cases of Zika virus infection were laboratory confirmed through reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction. Of the 192 cases, 110 (57%) are from the state of Zulia.

WHO: Women who are pregnant should consider delaying travel to any area where locally acquired Zika infection is occurring.

Saturday, February 13th, 2016Precautionary measures for pregnant women and women considering pregnancy

Based on the latest evidence that Zika virus infection during pregnancy may be linked to microcephaly in newborns, WHO is issuing further precautionary travel advice to women who are pregnant and their sexual partners.

Women who are pregnant should discuss their travel plans with their health care provider and consider delaying travel to any area where locally acquired Zika infection is occurring.

Zika virus is spread by mosquitoes, and not by person-to-person contact, though a small number of cases of sexual transmission have been documented.

Zika has been found in human semen. Two reports have described cases where Zika has been transmitted from one person to another through sexual contact.

Until more is known about the risk of sexual transmission, all men and women returning from an area where Zika is circulating – especially pregnant women and their partners – should practice safe sex, including through the correct and consistent use of condoms.

All travellers, including pregnant women, going to an area where locally acquired Zika infection is occurring should adhere closely to steps that can prevent mosquito bites during the trip. These include:

- using insect repellent: repellents may be applied to exposed skin or to clothing, and should contain DEET. Repellents must be used in strict accordance with the label instructions;

- wearing clothes (preferably light-coloured) that cover as much of the body as possible;

- using physical barriers such as screens, closed doors and windows;

- sleeping under mosquito nets, especially during the day, when Aedes mosquitoes are most active; and

- identifying and eliminating potential mosquito breeding sites, by emptying, cleaning or covering containers that can hold even small amounts of water, such as buckets, vases, flower pots and tyres.