Archive for the ‘Dengue’ Category

TAK-003: A new vaccine to prevent dengue may be on the horizon.

Friday, November 8th, 2019

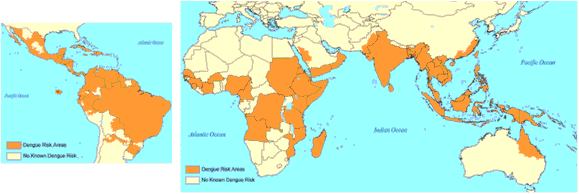

“….The World Health Organization this year listed dengue as one of the top 10 threats to global health.

The mosquito-borne disease is a growing threat for several reasons. First, the sheer number of dengue cases has been increasing dramatically in recent years. The WHO says there’s been a 30-fold increase in infections since 1970. Last year nearly 100 million people came down with the disease, also known as breakbone fever.

Second, there’s no specific treatment for the viral disease. When outbreaks occur, local clinics can get overwhelmed with patients experiencing severe flu-like symptoms. Third, the disease is moving in to new areas as the mosquitoes that carry the dengue virus expand their range……results just published in the New England Journal of Medicine……. found TAK-003 to be 80% effective in preventing participants from getting dengue and 95% effective in preventing cases of severe dengue………The Takeda dengue vaccine still needs to win regulatory approval before it’s made available to the public. Company officials, however, are confident they’ll get it. This week Takeda opened a 100 million-euro factory in Germany exclusively to manufacture TAK-003……..”

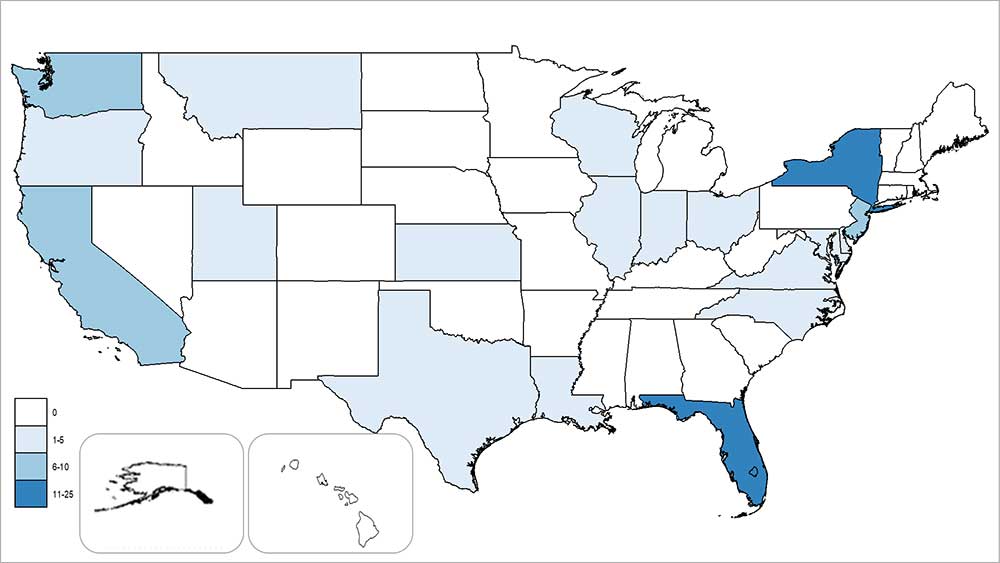

States and territories† reporting dengue cases – United States, 2019 (as of October 2, 2019)

The Philippines is experiencing an alarming dengue outbreak with more than 115,000 cases reported since the beginning of the year with 491 deaths, 30 per cent of them children between the ages of 5 and 9.

Tuesday, July 30th, 2019Of Honduras’s 32 public hospitals, 26 are overflowing with patients due to a dengue fever epidemic.

Sunday, July 28th, 2019“……..The disease has struck 28,000 people this year, of which 54, mostly children, have died...…”

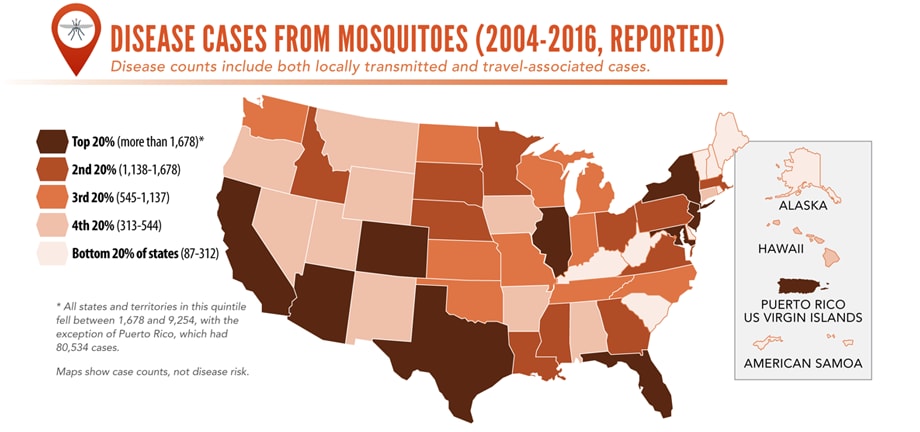

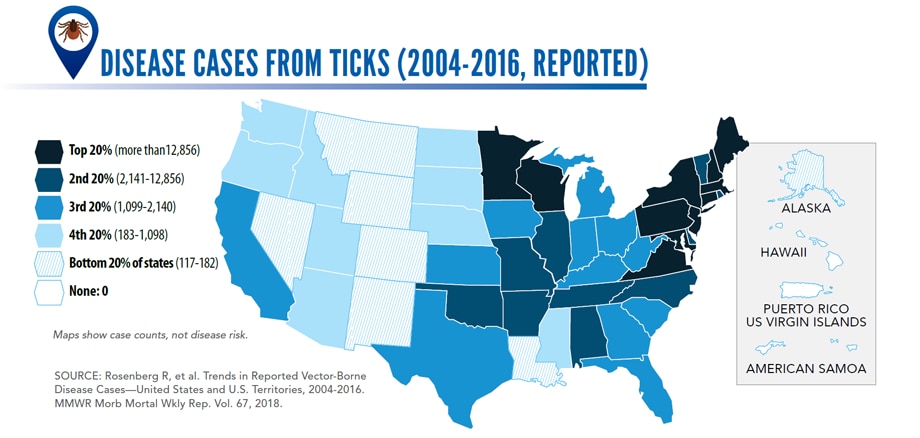

Illnesses on the rise from mosquito, tick, and flea bites

Sunday, June 2nd, 2019Almost everyone has been bitten by a mosquito, tick, or flea. These can be vectors for spreading pathogens (germs). A person who gets bitten by a vector and gets sick has a vector-borne disease, like dengue, Zika, Lyme, or plague. Between 2004 and 2016, more than 640,000 cases of these diseases were reported, and 9 new germs spread by bites from infected mosquitoes and ticks were discovered or introduced in the US. State and local health departments and vector control organizations are the nation’s main defense against this increasing threat. Yet, 84% of local vector control organizations lack at least 1 of 5 core vector control competencies. Better control of mosquitoes and ticks is needed to protect people from these costly and deadly diseases.

State and local public health agencies can

- Build and sustain public health programs that test and track germs and the mosquitoes and ticks that spread them.

- Train vector control staff on 5 core competencies for conducting prevention and control activities. http://bit.ly/2FG1OMwExternal

- Educate the public about how to prevent bites and control germs spread by mosquitoes, ticks, and fleas in their communities.

Increasing threat, limited capacity to respond

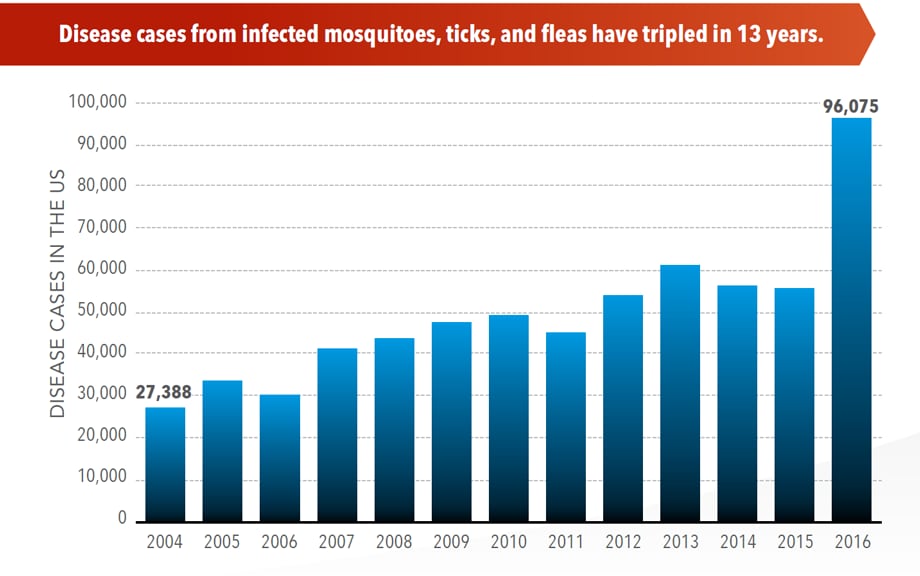

More cases in the US (2004-2016)

- The number of reported cases of disease from mosquito, tick, and flea bites has more than tripled.

- More than 640,000 cases of these diseases were reported from 2004 to 2016.

- Disease cases from ticks have doubled.

- Mosquito-borne disease epidemics happen more frequently.

More germs (2004-2016)

- Chikungunya and Zika viruses caused outbreaks in the US for the first time.

- Seven new tickborne germs can infect people in the US.

More people at risk

- Commerce moves mosquitoes, ticks, and fleas around the world.

- Infected travelers can introduce and spread germs across the world.

- Mosquitoes and ticks move germs into new areas of the US, causing more people to be at risk.

The US is not fully prepared

-

- Local and state health departments and vector control organizations face increasing demands to respond to these threats.

- More than 80% of vector control organizations report needing improvement in 1 or more of 5 core competencies, such as testing for pesticide resistance.

- More proven and publicly accepted mosquito and tick control methods are needed to prevent and control these diseases.

Honduras: 6,883 cases of dengue fever since the first of the year.

Saturday, June 1st, 2019Laboratory-positive travel-associated and locally-transmitted dengue cases from the 50 states and five territories – United States, 2019 as of May 1, 2019.

First FDA-approved vaccine for the prevention of dengue disease in endemic regions

Friday, May 3rd, 2019- May 01, 2019

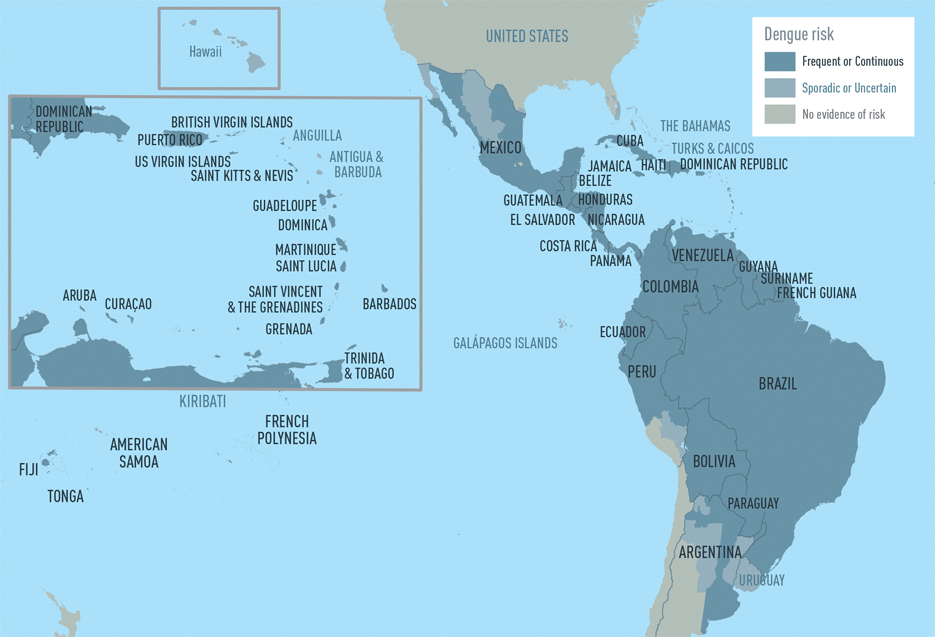

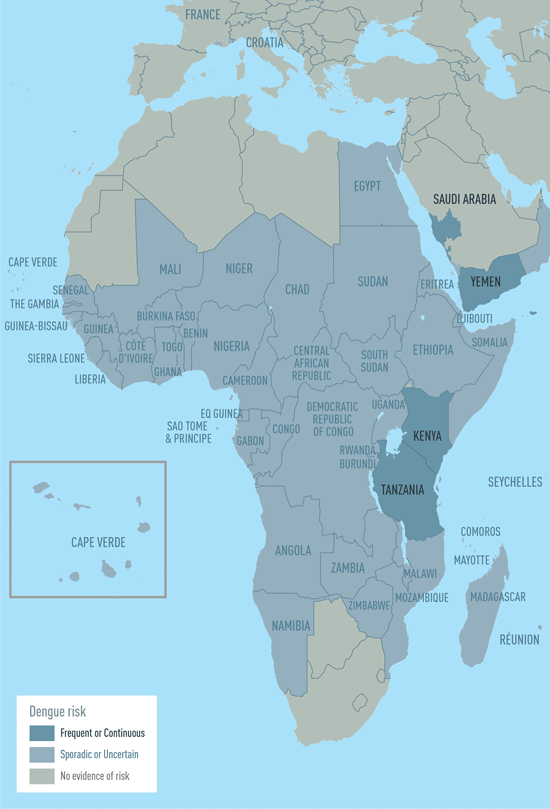

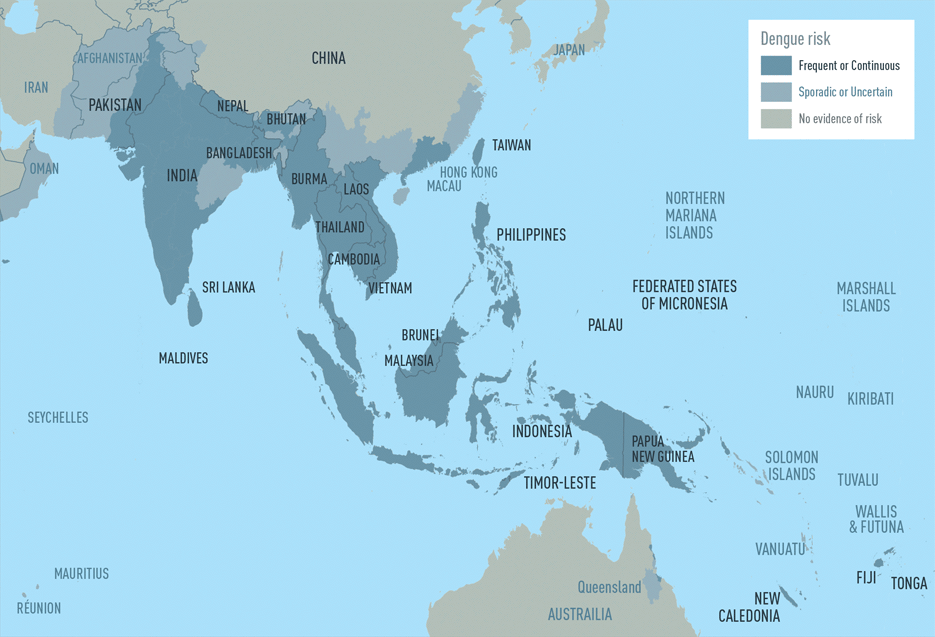

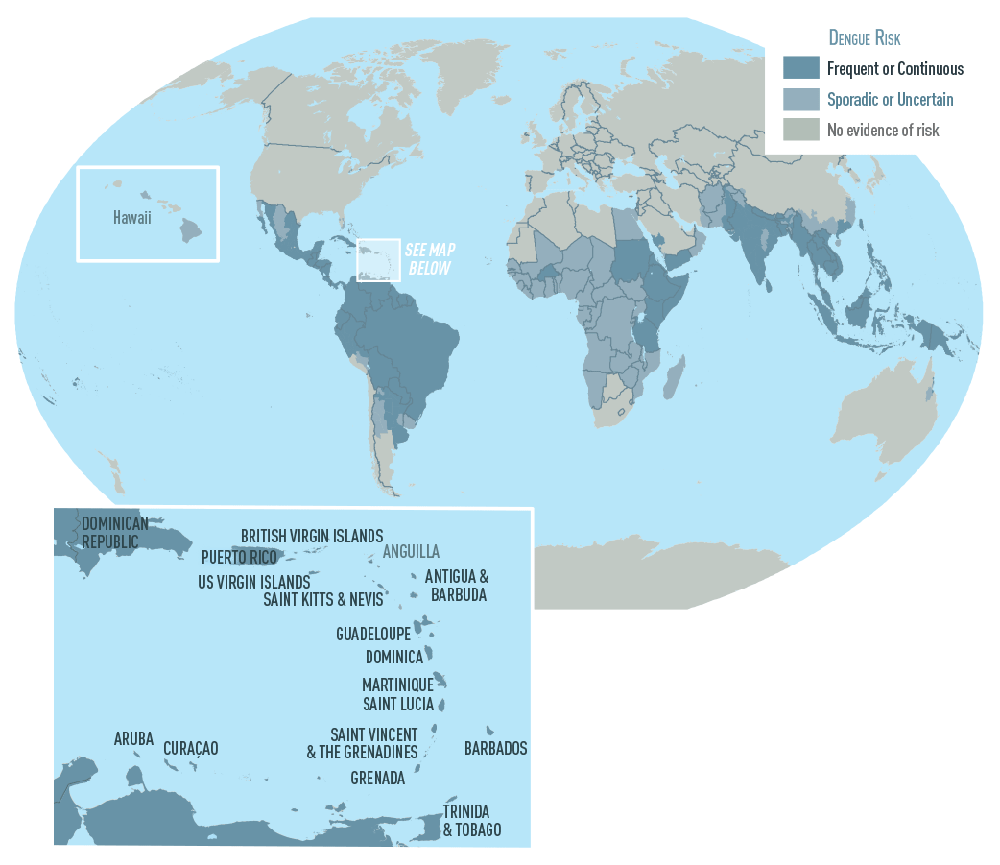

The U.S. Food and Drug Administration announced today the approval of Dengvaxia, the first vaccine approved for the prevention of dengue disease caused by all dengue virus serotypes (1, 2, 3 and 4) in people ages 9 through 16 who have laboratory-confirmed previous dengue infection and who live in endemic areas. Dengue is endemic in the U.S. territories of American Samoa, Guam, Puerto Rico and the U.S. Virgin Islands.

“Dengue disease is the most common mosquito-borne viral disease in the world and global incidence has increased in recent decades,” said Anna Abram, FDA deputy commissioner for policy, legislation, and international affairs. “The FDA is committed to working proactively with our partners at the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, as well as international partners, including the World Health Organization, to combat public health threats, including through facilitating the development and availability of medical products to address emerging infectious diseases. While there is no cure for dengue disease, today’s approval is an important step toward helping to reduce the impact of this virus in endemic regions of the United States.”

The CDC estimates more than one-third of the world’s population is living in areas at risk for infection by dengue virus which causes dengue fever, a leading cause of illness among people living in the tropics and subtropics. The first infection with dengue virus typically results in either no symptoms or a mild illness that can be mistaken for the flu or another viral infection. A subsequent infection can lead to severe dengue, including dengue hemorrhagic fever (DHF), a more severe form of the disease that can be fatal. Symptoms may include stomach pain, persistent vomiting, bleeding, confusion and difficulty breathing. Approximately 95 percent of all severe/hospitalized cases of dengue are associated with second dengue virus infection. Because there are no specific drugs approved for the treatment of dengue disease, care is limited to the management of symptoms.

Each year, an estimated 400 million dengue virus infections occur globally according to the CDC. Of these, approximately 500,000 cases develop into DHF, which contributes to about 20,000 deaths, primarily among children. Although dengue cases are rare in the continental U.S., the disease is regularly found in American Samoa, Puerto Rico, Guam, the U.S. Virgin Islands, as well as Latin America, Southeast Asia and the Pacific islands.

“Infection by one type of dengue virus usually provides immunity against that specific serotype, but a subsequent infection by any of the other three serotypes of the virus increases the risk of developing severe dengue disease, which may lead to hospitalization or even death,” said Peter Marks, M.D., director of the FDA’s Center for Biologics Evaluation and Research. “As the second infection with dengue is often much more severe than the first, the FDA’s approval of this vaccine will help protect people previously infected with dengue virus from subsequent development of dengue disease.”

The safety and effectiveness of the vaccine was determined in three randomized, placebo-controlled studies involving approximately 35,000 individuals in dengue-endemic areas, including Puerto Rico, Latin America and the Asia Pacific region. The vaccine was determined to be approximately 76 percent effective in preventing symptomatic, laboratory-confirmed dengue disease in individuals 9 through 16 years of age who previously had laboratory-confirmed dengue disease. Dengvaxia has already been approved in 19 countries and the European Union.

The most commonly reported side effects by those who received Dengvaxia were headache, muscle pain, joint pain, fatigue, injection site pain and low-grade fever. The frequency of side effects was similar across Dengvaxia and placebo recipients and tended to decrease after each subsequent dose of the vaccine.

Dengvaxia is not approved for use in individuals not previously infected by any dengue virus serotype or for whom this information is unknown. This is because in people who have not been infected with dengue virus, Dengvaxia appears to act like a first dengue infection – without actually infecting the person with wild-type dengue virus – such that a subsequent infection can result in severe dengue disease.Therefore, health care professionals should evaluate individuals for prior dengue infection to avoid vaccinating individuals who have not been previously infected by dengue virus. This can be assessed through a medical record of a previous laboratory-confirmed dengue infection or through serological testing (tests using blood samples from the patient) prior to vaccination.

Dengvaxia is a live, attenuated vaccine that is administered as three separate injections, with the initial dose followed by two additional shots given six and twelve months later.

The FDA granted this application Priority Review and a Tropical Disease Priority Review Voucher under a program intended to encourage development of new drugs and biologics for the prevention and treatment of certain tropical diseases. The approval was granted to Sanofi Pasteur.

The FDA, an agency within the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, protects the public health by assuring the safety, effectiveness, and security of human and veterinary drugs, vaccines and other biological products for human use, and medical devices. The agency also is responsible for the safety and security of our nation’s food supply, cosmetics, dietary supplements, products that give off electronic radiation, and for regulating tobacco products.

###

New research shows that the geographical range of vector-borne diseases such as chikungunya, dengue fever, leishmaniasis, and tick-borne encephalitis (TBE) is expanding rapidly.

Tuesday, April 16th, 2019“……..Global warming has allowed mosquitoes, ticks and other disease-carrying insects to proliferate, adapt to different seasons, and invade new territories across Europe over the past decade–with accompanying outbreaks of dengue in France and Croatia, malaria in Greece, West Nile Fever in Southeast Europe, and chikungunya virus in Italy and France. …….”

Dengue fever – Jamaica: 339 suspected and confirmed cases, including 6 deaths, reported from Jan 1 through Jan 21

Tuesday, February 5th, 2019Dengue fever – Jamaica

On 3 January 2019, the International Health Regulations (IHR) National Focal Point of Jamaica notified WHO of an increase in dengue cases in Jamaica.

From 1 January though 21 January 2019, 339 suspected and confirmed cases including six deaths were reported (Figure 1). In 2018, a total of 986 suspected and confirmed cases of dengue including 13 deaths have been reported. The number of reported dengue cases in 2018 was 4.5 times higher than that reported in 2017 (215 cases including six deaths). Cases reported to date for 2019 exceed the epidemic threshold (Figure 2).

According to historic data, Jamaica reported a major outbreak in 2016, when 2297 cases of dengue infection including two deaths were reported. Dengue virus 3 (DENV3) and DENV4 circulations were confirmed at the time.

By the end of 2018, the largest number of reported cases were notified by Kingston and Saint Andrew parishes. In 2019 so far, the largest proportion of cases have been reported by Saint Catherine parish.

Laboratory tests have identified DENV3 as the dengue serotype currently circulating.

In January 2019, some countries and territories in the Caribbean region, such as Guadeloupe, Martinique, and Saint Martin, reported an increase in dengue cases. Of note, in Saint Martin and Guadeloupe, serotype DENV1 is currently circulating.

Figure 1. Dengue fever cases and deaths by week of onset from 1 January 2018 through 21 January 2019 in Jamaica*

Public health response

- The Ministry of Health (MoH) declared the dengue outbreak on 3 January 2019.

- Health authorities in Jamaica are implementing measures for the following activities; strengthened integrated vector control, enhanced surveillance of cases, social mobilization, clinical management, enhanced laboratory diagnostic capacity, and emergency risk communications.

- The MoH has been collaborating with the Pan American Health Organization (PAHO/WHO) and other international agencies to strengthen and co-ordinate the response activities.

- Since July 2018, the MoH has intensified its vector control activities.

- The MoH launched the Emergency Operations Centre on 27 December 2018; and fully activated it on 3 January 2019 to facilitate the coordination and reporting of activities. The response activities are geared towards strengthening the response capacity with adequate human resources, as well as supporting efforts to reduce the entomological indices for the Aedes aegypti mosquito across the island and enhancing clinical management capacity.

WHO risk assessment

Jamaica has been reporting dengue cases since 1990 and throughout 2018; however, an increase has been observed since December 2018 exceeding the epidemic threshold. Similar large increases were reported in 2010 (2887 cases), 2012 (4670 cases), and 2016 (2297 cases). The increase of dengue in the Caribbean islands may result in more severe secondary dengue virus infections and require comprehensive risk communication.

WHO advice

On 21 November 2018, PAHO/WHO alerted Member States about an increase in dengue cases in countries and territories in the Americas and recommended coordinated actions both inside and outside of the health sector, including prioritizing activities to prevent transmission of dengue as well as deaths due to this disease.

PAHO/WHO further advises to follow the key recommendations regarding outbreak preparedness and response, case management, laboratory, and integrated vector management as published in the 21 November 2018 PAHO/WHO Epidemiological Update on Dengue, available at the link below.

There is no specific treatment for disease due to dengue; therefore, prevention is the most important step to reduce the risk of dengue infection. WHO recommends proper and timely case management of dengue cases. Surveillance should continue to be strengthened within all affected areas and at the national level. Key public health communication messages should continue to be provided to reduce the risk of transmission of dengue in the population.

In addition, integrated vector management (IVM) activities should be enhanced to remove potential breeding sites, reduce vector populations, and minimize individual exposures. This should include both larval and adult vector control strategies (i.e. environmental management and source reduction, and chemical control measures), as well as strategies to protect individuals and households. Where indoor biting occurs, household insecticide aerosol products, mosquito coils, or other insecticide vaporizers may also reduce biting activity. Household fixtures such as window and door screens and air conditioning can also reduce biting. Since Aedes mosquitoes (the primary vector for transmission) are day-biting mosquitoes, personal protective measures such as use of clothing that minimizes skin exposure during daylight hours is recommended. Repellents may be applied to exposed skin or to clothing. The use of repellents must be in strict accordance with label instructions. Insecticide-treated mosquito nets afford good protection for those who sleep during the day (e.g. infants, the bedridden, and night-shift workers) as well as during the night to prevent mosquito bites.

WHO does not recommend any general travel or trade restrictions be applied based on the information available for this event.

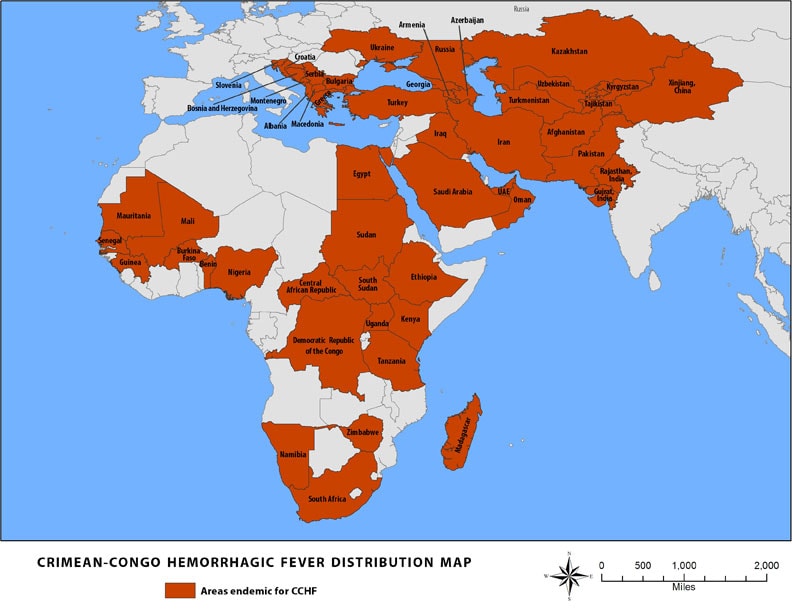

Pakistan: Report on Dengue and Crimean-Congo Fever

Monday, November 12th, 2018“…..From 2015 till today, 51,764 people infected with dengue in the country of whom 107 people have died…….

The Congo virus on the other hand, has infected 613 people in the same time period. Of these people, 148 died due to the disease….”