Archive for the ‘Hepatitis C’ Category

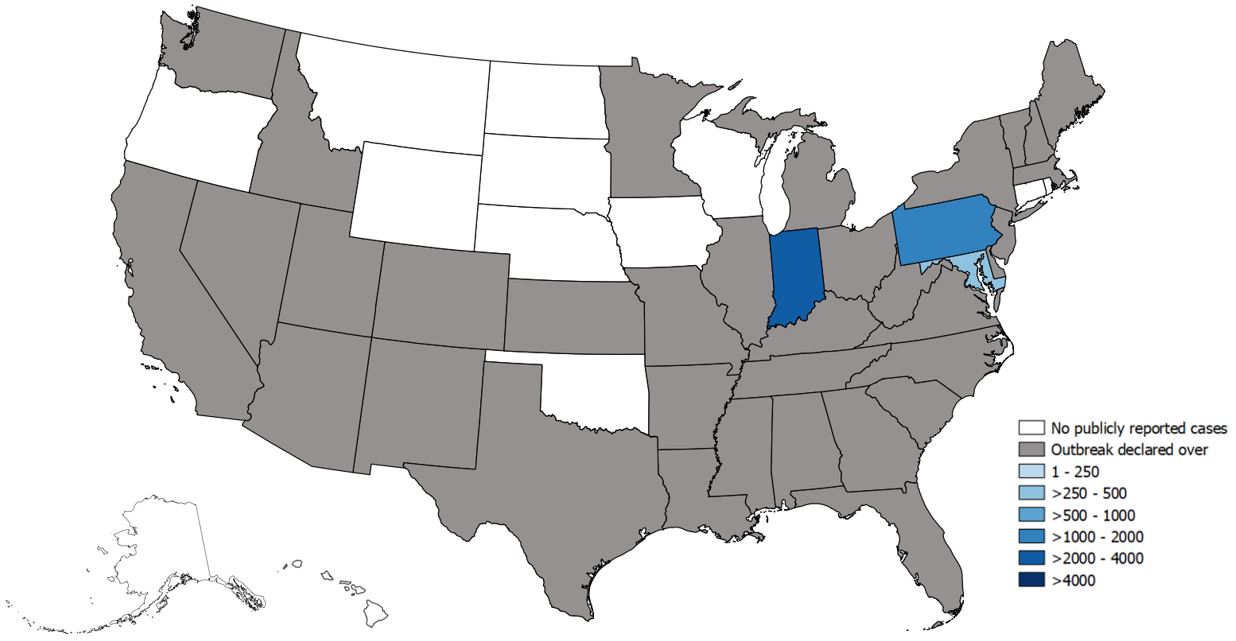

Widespread outbreaks of hepatitis A across the United States

Thursday, June 27th, 2019Since March 2017, CDC’s Division of Viral Hepatitis (DVH) has been assisting multiple state and local health departments with hepatitis A outbreaks, spread through person-to-person contact.

The hepatitis A vaccine is the best way to prevent HAV infection

- The following groups are at highest risk for acquiring HAV infection or developing serious complications from HAV infection in these outbreaks and should be offered the hepatitis A vaccine in order to prevent or control an outbreak:

- People who use drugs (injection or non-injection)

- People experiencing unstable housing or homelessness

- Men who have sex with men (MSM)

- People who are currently or were recently incarcerated

- People with chronic liver disease, including cirrhosis, hepatitis B, or hepatitis C

- One dose of single-antigen hepatitis A vaccine has been shown to control outbreaks of hepatitis A and provides up to 95% seroprotection in healthy individuals for up to 11 years.1,2

- Pre-vaccination serologic testing is not required to administer hepatitis A vaccine. Vaccinations should not be postponed if vaccination history cannot be obtained or records are unavailable.

CDC has provided outbreak-specific considerations for hepatitis A vaccine administration.

State-Reported Hepatitis A Outbreak Cases as of June 21, 2019

Weekly summary of major outbreaks in Africa

Wednesday, March 13th, 2019Plague: Uganda

2 Cases

1 Death: 50% CFR

Ebola virus disease: Democratic Republic of the Congo

921 Cases

582 Deaths: 63% CFR

Hepatitis E: Namibia

4 669 Cases

41 Deaths: 0.9% CFR

Lassa fever: Nigeria

420 Cases

93 Deaths: CFR 22.1%

Egypt is wiping out Hepatitis C at an unprecedented pace. How?

Monday, June 4th, 2018“…..The hepatitis C epidemic in Egypt—the country with the highest prevalence of the disease in the world—started around 50 years ago, when the government was attempting to get rid of one plague and ended up substituting it for another. For millennia the Nile Delta has been an ideal breeding ground for schistosomiasis, a parasite spread to humans by freshwater snails. In the mid-20th century, the Egyptian government conducted multiple mass-treatment campaigns using an injectable emetic—and needles were repeatedly reused. Hepatitis C virus, not yet known but transmitted efficiently by blood, was inadvertently spread to many citizens. By 2008, one in 10 Egyptians had chronic hepatitis C…..By 2015 hepatitis C accounted for 40,000 deaths per year in Egypt—7.6 percent of all deaths there—and depressed national GDP growth by 1.5 percent……..”

CDC on hepatitis

Sunday, November 26th, 2017Viral hepatitis is the term that describes inflammation of the liver that is caused by a virus. There are actually five types of hepatitis viruses; each one is named after a letter in the alphabet: A, B, C, D and E.

The most common types of viral hepatitis are A, B and C. These three viruses affect millions of people worldwide, causing both short-term illness and long-term liver disease. The World Health Organization estimates 325 million people worldwide are living with chronic hepatitis B or chronic hepatitis C. In 2015, 1.34 million died from viral hepatitis, a number that is almost equal to the number of deaths caused by tuberculosis and HIV combined.

Hepatitis B and hepatitis C are the most common types of viral hepatitis in the United States, and can cause serious health problems, including liver failure and liver cancer. In the U.S., an estimated 3.5 million people are living with hepatitis C in the US and an estimated 850,000 are living with Hepatitis B. Unfortunately, new liver cancer cases and deaths are on the rise in the United States. This increase is believed to be related to infection with hepatitis B or hepatitis C.

Many people are unaware that they have been infected with hepatitis B and hepatitis C, because many people do not have symptoms or feel sick. CDC developed an online Hepatitis Risk Assessment to help determine if you should get tested or vaccinated for viral hepatitis. The assessment takes only five minutes and will provide personalized testing and vaccination recommendations for hepatitis A, hepatitis B, and hepatitis C.

Hepatitis A

Hepatitis A is a short-term disease caused by infection with the hepatitis A virus. Hepatitis A is usually spread when a person ingests the virus from contact with objects, food, or drinks contaminated by solid waste from an infected person. Hepatitis A was once very common in the United States, but now less than 3,000 cases are estimated to occur every year. Hepatitis A does not lead to liver cancer and most people who get infected recover over time with no lasting effects. However, the disease can be fatal for people in poor health or with certain medical conditions.

Hepatitis A is easily prevented with a safe and effective vaccine, which is believed to have caused the dramatic decline in new cases in recent years. The vaccine is recommended for all children at one year of age and for adults who may be at risk, including people traveling to certain international countries.

Hepatitis B

Hepatitis B is a liver disease that results after infection with the hepatitis B virus. Hepatitis B is common in many parts of the world, including Asia, the Pacific Islands and Africa. Like Hepatitis A, Hepatitis B is also preventable with a vaccine. The hepatitis B virus can be passed from an infected woman to her baby at birth, if her baby does not receive the hepatitis B vaccine. As a result, the hepatitis B vaccine is recommended for all infants at birth.

Unfortunately, many people got infected with hepatitis B before the vaccine was widely available. This is why CDC recommends anyone born in areas where hepatitis B is common, or who have parents who were born in these regions, get tested for hepatitis B. Treatments are available that can delay or reduce the risk of developing liver cancer.

Hepatitis C

Hepatitis C is a liver disease that results from infection with the hepatitis C virus. For reasons that are not entirely understood, people born from 1945 to 1965 are five times more likely to have hepatitis C than other age groups. In the past, hepatitis C was spread through blood transfusions and organ transplants. However, widespread screening of the blood supply in the United States began in 1990.The hepatitis C virus was virtually eliminated from the blood supply by 1992. Today, most people become infected with hepatitis C by sharing needles, syringes, or any other equipment to inject drugs. In fact, rates of new infections have been on the rise since 2010 in young people who inject drugs.

There is currently no vaccine to prevent hepatitis C. Fortunately, new treatments offer a cure for most people. Once diagnosed, most people with hepatitis C can be cured in just 8 to 12 weeks, which reduces their risk for liver cancer.

Find out if you should get tested or vaccinated for viral hepatitis by taking CDC’s quick online Hepatitis Risk Assessment.

For more information visit www.cdc.gov/hepatitis.

Stay Connected

- Join the conversation on hepatitis by following @cdchep on Twitter.

- Sign up for email updates from CDC’s Division of Viral Hepatitis.

Learn more

Médecins Sans Frontières (MSF) has announced that it has secured deals for generic hepatitis C medicines for as low as US$1.40 per day, or $120 per 12-week treatment course for the key medicines sofosbuvir and daclatasvir.

Thursday, November 2nd, 2017“…..In the US, pharmaceutical corporation Gilead launched sofosbuvir at $1,000 per pill in 2013; Bristol-Myers Squibb (BMS) launched daclatasvir at $750 per pill in 2015. This led to the original price tag of $147,000 for a person’s 12-week combination treatment course. The corporations have also been charging exorbitant prices in many developing countries, paralysing the launch of national treatment programmes and causing treatment rationing in many countries around the world….”

Hepatitis C FAQs for Health Professionals

What is the case definition for acute hepatitis C?

Because the clinical characteristics are similar for all types of acute viral hepatitis, the specific viral cause of illness cannot be determined solely on the basis of signs, symptoms, history, or current risk factors, but must be verified by specific serologic testing. For specific serologic tests required to meet the case definition, see the following link:

What is the case definition for chronic hepatitis C?

Laboratory testing is required for confirmation of the etiologic cause of viral hepatitis. For specific serologic tests, see the following link:

Is additional guidance on viral hepatitis Case determination and surveillance available?

Yes. See the Guidelines for Viral Hepatitis Surveillance and Case Management, available here(https://www.cdc.gov/hepatitis/scripts/sharebuttononoff.js).

What is the incidence of HCV infection in the United States?

In 2014, a total of 2,194 cases of acute hepatitis C were reported to CDC from 40 states. The overall incidence rate for 2014 was 0.7 cases per 100,000 population, an increase from 2010–2012. After adjusting for under-ascertainment and under-reporting, an estimated 30,500 acute hepatitis C cases occurred in 2014.

What is the prevalence of chronic HCV infection in the United States?

An estimated 2.7-3.9 million people in the United States have chronic hepatitis C.

Who is at risk for HCV infection?

The following persons are at known to be at increased risk for HCV infection:

- Current or former injection drug users, including those who injected only once many years ago

- Recipients of clotting factor concentrates made before 1987, when more advanced methods for manufacturing those products were developed

- Recipients of blood transfusions or solid organ transplants before July 1992, when better testing of blood donors became available

- Chronic hemodialysis patients

- Persons with known exposures to HCV, such as

- health care workers after needlesticks involving HCV-positive blood

- recipients of blood or organs from a donor who tested HCV-positive

- Persons with HIV infection

- Children born to HCV-positive mothers

Is it possible for someone to become infected with HCV and then spontaneously clear the infection?

Yes. Approximately 15%–25% of persons clear the virus from their bodies without treatment and do not develop chronic infection; the reasons for this are not well known.

How likely is HCV infection to become chronic?

HCV infection becomes chronic in approximately 75%–85% of cases.

Why do most persons remain chronically infected with HCV?

A person infected with HCV mounts an immune response to the virus, but replication of the virus during infection can result in changes that evade the immune response. This may explain how the virus establishes and maintains chronic infection.

What are the chances of someone developing chronic HCV infection, chronic liver disease, cirrhosis, or liver cancer or dying as a result of hepatitis C?

Of every 100 persons infected with HCV, approximately

- 75–85 will go on to develop chronic infection

- 60–70 will go on to develop chronic liver disease

- 5–20 will go on to develop cirrhosis over a period of 20–30 years

- 1–5 will die from the consequences of chronic infection (liver cancer or cirrhosis)

Can persons become infected with a different strain of HCV after they have cleared the initial infection?

Yes. Prior infection with HCV does not protect against later infection with the same or different genotypes(https://www.cdc.gov/osels/ph_surveillance/nndss/casedef/hepatitisccurrent.htm) of the virus. This is because persons infected with HCV typically have an ineffective immune response due to changes in the virus during infection. For the same reason, no effective pre- or postexposure prophylaxis (i.e., immune globulin) is available.

Is hepatitis C a common cause for liver transplantation?

Yes. Chronic HCV infection is the leading indication for liver transplants in the United States.

How many deaths can be attributed to chronic HCV infection?

CDC estimates that there were 19,659 deaths with HCV as an underlying or contributing cause of death in 2014. Current information indicates these represent a fraction of deaths attributable in whole or in part to chronic hepatitis C.

Is there a hepatitis C vaccine?

No vaccine for hepatitis C is available. Research into the development of a vaccine is under way.

Transmission and Symptoms

How is HCV transmitted?

HCV is transmitted primarily through large or repeated percutaneous (i.e., passage through the skin) exposures to infectious blood, such as

- Injection drug use (currently the most common means of HCV transmission in the United States)

- Receipt of donated blood, blood products, and organs (once a common means of transmission but now rare in the United States since blood screening became available in 1992)

- Needlestick injuries in health care settings

- Birth to an HCV-infected mother

HCV can also be spread infrequently through

- Sex with an HCV-infected person (an inefficient means of transmission)

- Sharing personal items contaminated with infectious blood, such as razors or toothbrushes (also inefficient vectors of transmission)

- Other health care procedures that involve invasive procedures, such as injections (usually recognized in the context of outbreaks)

What is the prevalence of HCV infection among injection drug users (IDUs)?

The most recent surveys of active IDUs indicate that approximately one third of young (aged 18–30 years) IDUs are HCV-infected. Older and former IDUs typically have a much higher prevalence (approximately 70%–90%) of HCV infection, reflecting the increased risk of continued injection drug use. The high HCV prevalence among former IDUs is largely attributable to needle sharing during the 1970s and 1980s, before the risks of bloodborne viruses were widely known and before educational initiatives were implemented.

Is cocaine use associated with HCV transmission?

There are very limited epidemiologic data to suggest an additional risk from non-injection (snorted or smoked) cocaine use, but this risk is difficult to differentiate from associated injection drug use and sex with HCV-infected partners.

What is the risk of acquiring HCV infection from transfused blood or blood products in the United States?

Now that more advanced screening tests for HCV are used in blood banks, the risk is considered to be less than 1 chance per 2 million units transfused. Before 1992, when blood screening for HCV became available, blood transfusion was a leading means of HCV transmission.

Can HCV be spread during medical or dental procedures?

As long as Standard Precautions(https://www.cdc.gov/ncidod/dhqp/gl_isolation_standard.html) and other infection control practices are used consistently, medical and dental procedures performed in the United States generally do not pose a risk for the spread of HCV. However, HCV has been spread in health care settings when injection equipment, such as syringes, was shared between patients or when injectable medications or intravenous solutions were mishandled and became contaminated with blood. Health care personnel should understand and adhere to Standard Precautions, which includes Injection Safety(https://www.cdc.gov/ncidod/dhqp/gl_isolation_standard.html) practices aimed at reducing bloodborne pathogen risks for patients and health care personnel. If health care-associated HCV infection is suspected, this should be reported to state and local public health authorities.

Can HCV be spread within a household?

Yes, but this does not occur very often. If HCV is spread within a household, it is most likely a result of direct, through-the-skin exposure to the blood of an infected household member.

What are the signs and symptoms of acute HCV infection?

Persons with newly acquired HCV infection usually are asymptomatic or have mild symptoms that are unlikely to prompt a visit to a health care professional. When symptoms occur, they can include:

- Fever

- Fatigue

- Dark urine

- Clay-colored stool

- Abdominal pain

- Loss of appetite

- Nausea

- Vomiting

- Joint pain

- Jaundice

What percentage of persons infected with HCV develop symptoms of acute illness?

Approximately 20%–30% of those newly infected with HCV experience fatigue, abdominal pain, poor appetite, or jaundice.

How soon after exposure to HCV do symptoms appear?

In those persons who do develop symptoms, the average time period from exposure to symptom onset is 4–12 weeks (range: 2–24 weeks).

What are the signs and symptoms of chronic HCV infection?

Most persons with chronic HCV infection are asymptomatic. However, many have chronic liver disease, which can range from mild to severe, including cirrhosis and liver cancer. Chronic liver disease in HCV-infected persons is usually insidious, progressing slowly without any signs or symptoms for several decades. In fact, HCV infection is often not recognized until asymptomatic persons are identified as HCV-positive when screened for blood donation or when elevated alanine aminotransferase (ALT, a liver enzyme) levels are detected during routine examinations.

Testing and Diagnosis

Who should be tested for HCV infection?

HCV testing is recommended for anyone at increased risk for HCV infection, including:

- Persons born from 1945 through 1965

- Persons who have ever injected illegal drugs, including those who injected only once many years ago

- Recipients of clotting factor concentrates made before 1987

- Recipients of blood transfusions or solid organ transplants before July 1992

- Patients who have ever received long-term hemodialysis treatment

- Persons with known exposures to HCV, such as

- health care workers after needlesticks involving HCV-positive blood

- recipients of blood or organs from a donor who later tested HCV-positive

- All persons with HIV infection

- Patients with signs or symptoms of liver disease (e.g., abnormal liver enzyme tests)

- Children born to HCV-positive mothers (to avoid detecting maternal antibody, these children should not be tested before age 18 months)

What blood tests are used to detect HCV infection?

Several blood tests are performed to test for HCV infection, including:

- Screening tests for antibody to HCV (anti-HCV)

- enzyme immunoassay (EIA)

- enhanced chemiluminescence immunoassay (CIA)

- Qualitative tests to detect presence or absence of virus (HCV RNA polymerase chain reaction [PCR])

- Quantitative tests to detect amount (titer) of virus (HCV RNA PCR)

How do I interpret the different tests for HCV infection?

A table on the interpretation of results of tests for hepatitis C Virus (HCV) infection and further actions is available at https://www.cdc.gov/hepatitis/HCV/PDFs/hcv_graph.pdf[PDF – 1 page](https://www.cdc.gov/hepatitis/hcv/pdfs/hcv_graph.pdf).

Is an algorithm for HCV diagnosis available?

A flow chart that outlines the serologic testing process beginning with anti HCV testing is available at https://www.cdc.gov/hepatitis/HCV/PDFs/hcv_flow.pdf [PDF – 1 page](https://www.cdc.gov/hepatitis/scripts/sharebuttononoff.js).

How soon after exposure to HCV can anti-HCV be detected?

HCV infection can be detected by anti-HCV screening tests (enzyme immunoassay) 4–10 weeks after infection. Anti-HCV can be detected in >97% of persons by 6 months after exposure.

How soon after exposure to HCV can HCV RNA be detected by PCR?

HCV RNA appears in blood and can be detected as early as 2–3 weeks after infection.

Under what circumstances is a false-positive anti-HCV test result likely?

False-positive anti-HCV tests appear more often when persons at low risk for HCV infection (e.g., blood donors) are tested. Therefore, it is important to follow-up all positive anti-HCV tests with a RNA test to establish current infection.

Under what circumstances might a false-negative anti-HCV test result occur?

Persons with early HCV infection might not yet have developed antibody levels high enough that the test can measure. In addition, some persons might lack the (immune) response necessary for the test to work well. In these persons, further testing such as PCR for HCV RNA may be considered.

Can a patient have a normal liver enzyme (e.g., ALT) level and still have chronic hepatitis C?

Yes. It is common for patients with chronic hepatitis C to have liver enzyme levels that go up and down, with periodic returns to normal or near normal levels. Liver enzyme levels can remain normal for over a year despite chronic liver disease.

Where can I learn more about hepatitis C serology?

CDC offers an online training that covers the serology of acute and chronic hepatitis C and other types of viral hepatitis, available at https://www.cdc.gov/hepatitis/resources/professionals/training/serology/training.htm(https://www.cdc.gov/hepatitis/resources/professionals/training/serology/training.htm).

Management and Treatment

What should be done for a patient with confirmed HCV infection?

HCV-positive persons should be evaluated (by referral or consultation, if appropriate) for presence of chronic liver disease, including assessment of liver function tests, evaluation for severity of liver disease and possible treatment, and determination of the need for Hepatitis A and Hepatitis B vaccination.

When might a specialist be consulted in the management of HCV-infected persons?

Any physician who manages a person with hepatitis C should be knowledgeable and current on all aspects of the care of a person with hepatitis C; this can include some internal medicine and family practice physicians as well as specialists such as infectious disease physicians, gastroenterologists, or hepatologists.

What is the treatment for acute hepatitis C?

Treatment for acute hepatitis C is similar to treatment for chronic hepatitis C. This issue was addressed in the 2009 AASLD Practice Guidance, the response rate to treatment is higher among persons with acute than with chronic HCV infection. However, the optimal treatment regimen and when it should be initiated remains uncertain.

What is the treatment for chronic hepatitis C?

The treatment for hepatitis C virus (HCV) infection has evolved substantially since the introduction of highly effective HCV protease inhibitor therapies in 2011. Since that time new drugs with different mechanisms of action have become and continue to become available. For a complete list of currently approved FDA therapies to treat hepatitis C, please visit http://www.hepatitisc.uw.edu/page/treatment/drugs.

To provide healthcare professionals with timely guidance as new therapies are available and integrated into HCV regimens, the Infectious Diseases Society of America (IDSA) and American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases (AASLD), in collaboration with the International Antiviral Society–USA (IAS–USA), developed evidence-based, expert-developed recommendations for hepatitis C management: http://www.hcvguidelines.org.

How many different genotypes of HCV exist?

At least six distinct HCV genotypes (genotypes 1–6) and more than 50 subtypes have been identified. Genotype 1 is the most common HCV genotype in the United States.

Is it necessary to do viral genotyping when managing a person with chronic hepatitis C?

Yes. Because there are at least six known genotypes and more than 50 subtypes of HCV, genotype information is helpful in defining the epidemiology of hepatitis C and in making recommendations regarding appropriate treatment regimen. In the United States, HCV genotype 1 is most common, accounting for 74% of prevalent cases. Once the genotype is identified, it need not be tested again; genotypes do not change during the course of infection.

Can superinfection with more than one genotype of HCV occur?

Superinfection is possible if risk behaviors (e.g., injection drug use) for HCV infection continue, but it is believed to be very uncommon.

Does chronic hepatitis C affect only the liver?

A small percentage of persons with chronic HCV infection develop medical conditions due to hepatitis C that are not limited to the liver. These conditions are thought to be attributable to the body’s immune response to HCV infection. Such conditions can include:

- Diabetes mellitus, which occurs three times more frequently in HCV-infected persons

- Glomerulonephritis, a type of kidney disease caused by inflammation of the kidney

- Essential mixed cryoglobulinemia, a condition involving the presence of abnormal proteins in the blood

- Porphyria cutanea tarda, an abnormality in heme production that causes skin fragility and blistering

- Non-Hodgkins lymphoma, which might occur somewhat more frequently in HCV-infected persons

Counseling Patients

What topics should be discussed with patients who have HCV infection?

- Patients should be informed about the low but present risk for transmission with sex partners.

- Sharing personal items that might have blood on them, such as toothbrushes or razors, can pose a risk to others.

- Cuts and sores on the skin should be covered to keep from spreading infectious blood or secretions.

- Donating blood, organs, tissue, or semen can spread HCV to others.

- HCV is not spread by sneezing, hugging, holding hands, coughing, sharing eating utensils or drinking glasses, or through food or water.

- Patients may benefit from a joining support group.

What should HCV-infected persons be advised to do to protect their livers from further harm?

- HCV-positive persons should be advised to avoid alcohol because it can accelerate cirrhosis and end-stage liver disease.

- Viral hepatitis patients should also check with a health professional before taking any new prescription pills, over-the counter drugs (such as non-aspirin pain relievers), or supplements, as these can potentially damage the liver.

Should HCV-infected persons be restricted from working in certain occupations or settings?

CDC’s recommendations for prevention and control of HCV infection(https://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/preview/mmwrhtml/00055154.htm) specify that persons should not be excluded from work, school, play, child care, or other settings on the basis of their HCV infection status. There is no evidence of HCV transmission from food handlers, teachers, or other service providers in the absence of blood-to-blood contact.

Hepatitis C and Health Care Personnel

What is the risk for HCV infection from a needlestick exposure to HCV-contaminated blood?

After a needlestick or sharps exposure to HCV-positive blood, the risk of HCV infection is approximately 1.8% (range: 0%–10%).

Other than needlesticks, do other exposures, such as splashes to the eye, pose a risk to health care personnel for HCV transmission?

Although a few cases of HCV transmission via blood splash to the eye have been reported, the risk for such transmission is expected to be very low. Avoiding occupational exposure to blood is the primary way to prevent transmission of bloodborne illnesses among health care personnel. All health care personnel should adhere to Standard Precautions(https://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/preview/mmwrhtml/00055154.htm) . Depending on the medical procedure involved, Standard Precautions may include the appropriate use of personal protective equipment (e.g., gloves, masks, and protective eyewear).

Should HCV-infected health care personnel be restricted in their work?

There are no CDC recommendations to restrict a health care worker who is infected with HCV. The risk of transmission from an infected health care worker to a patient appears to be very low. All health care personnel, including those who are HCV positive, should follow strict aseptic technique and Standard Precautions(https://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/preview/mmwrhtml/00055154.htm) , including appropriate hand hygiene, use of protective barriers, and safe injection practices.

What is the recommended management of a health care worker with occupational exposure to HCV?

Postexposure prophylaxis (PEP) of hepatitis C is not recommended, as outlined in the 2001 MMWR on management of health-care personnel (HCP) who have occupational exposure to blood and other body fluids. Test the source for HCV RNA. If the source is HCV RNA positive, or if HCV infection status unknown, follow this testing algorithm[PDF – 2 pages](https://www.cdc.gov/hepatitis/pdfs/Testing-Followup-Exposed-HC-Personnel.pdf) (update to 2001 guidance).

After a needlestick or sharps exposure to HCV-positive blood, the risk of HCV infection is approximately 1.8%. If the health care worker does become infected, follow AASLD/IDSA guidelines for management and treatment of hepatitis C.

Pregnancy and HCV Infection

Should pregnant women be routinely tested for anti-HCV?

No. Since pregnant women have no greater risk of being infected with HCV than non-pregnant women and interventions to prevent mother-to-child transmission are lacking, routine anti-HCV testing of pregnant women is not recommended. Pregnant women should be tested for anti-HCV only if they have risk factors for HCV infection(https://www.cdc.gov/hepatitis/hcv/hcvfaq.htm#a6).

What is the risk that an HCV-infected mother will spread HCV to her infant during birth?

Approximately 6 of every 100 infants born to HCV-infected mothers become infected with the virus. Transmission occurs at the time of birth, and no prophylaxis is available to prevent it. The risk is increased by the presence of maternal HCV viremia at delivery and also is 2–3 times greater if the woman is coinfected with HIV. Most infants infected with HCV at birth have no symptoms and do well during childhood. More research is needed to find out the long-term effects of perinatal HCV infection.

Should a woman with HCV infection be advised against breastfeeding?

No. There is no evidence that breastfeeding spreads HCV. However, HCV-positive mothers should consider abstaining from breastfeeding if their nipples are cracked or bleeding.

When should children born to HCV-infected mothers be tested to see if they were infected at birth?

Children should be tested for anti-HCV no sooner than age 18 months because anti-HCV from the mother might last until this age. If diagnosis is desired before the child turns 18 months, testing for HCV RNA could be performed at or after the infant’s first well-child visit at age 1–2 months. HCV RNA testing should then be repeated at a subsequent visit, independent of the initial HCV RNA test result.

WHO: A record 3 million people were able to obtain treatment for hepatitis C over the past two years, and 2.8 million more people embarked on lifelong treatment for hepatitis B in 2016.

Thursday, November 2nd, 2017Close to 3 million people access hepatitis C cure

World Hepatitis Summit 2017 calls for accelerated action to eliminate viral hepatitis

31 October 2017 | São Paulo, Brazil – On the eve of the World Hepatitis Summit in Brazil, WHO reports increasing global momentum in the response to viral hepatitis. A record 3 million people were able to obtain treatment for hepatitis C over the past two years, and 2.8 million more people embarked on lifelong treatment for hepatitis B in 2016.

“We have seen a nearly 5-fold increase in the number of countries developing national plans to eliminate life-threatening viral hepatitis over the last 5 years,” says Dr Gottfried Hirnschall, Director of WHO’s Department of HIV and Global Hepatitis Programme. “These results bring hope that the elimination of hepatitis can and will become a reality.”

Hosted by the Government of Brazil, the World Hepatitis Summit 2017 is being co-organized by WHO and the World Hepatitis Alliance. The Summit aims to encourage more countries to take decisive action to tackle hepatitis, which still causes more than 1.3 million deaths every year and affects more than 325 million people.

“We cannot lose sight of the fact that last year 194 governments committed to eliminating viral hepatitis by 2030. For sure we are still a long way from this goal but that doesn’t mean it’s some unattainable dream. It’s eminently achievable. It just requires immediate action,” says Charles Gore, President of World Hepatitis Alliance. “The World Hepatitis Summit 2017 is all about how to turn WHO’s global strategy into concrete actions and inspire people to leave with a ‘can do’ attitude.”

“Brazil is honored to host the World Hepatitis Summit 2017 – and welcomes this extraordinary team of experts, researchers, managers and civil society representatives to discuss the global health problem posed by viral hepatitis,” says Dr Adele Schwartz Benzaken, Director of the Brazilian Ministry of Health’s Department of Surveillance, Prevention and Control of STIs, HIV/AIDS and Viral Hepatitis.”Brazil is committed to taking recent advances in its response to hepatitis forward – on the road to elimination.”

Progress in treatment and cure

Many countries are demonstrating strong political leadership, facilitating dramatic price reductions in hepatitis medicines, including through the use of generic medicines—which allow better access for more people within a short time.

In 2016, 1.76 million people were newly treated for hepatitis C , a significant increase on the 1.1 million people who were treated in 2015. The 2.8 million additional people starting lifelong treatment for hepatitis B in 2016 was a marked increase from the 1.7 million people starting it in 2015. But these milestones represent only initial steps – access to treatment must be increased globally if the 80% treatment target is to be reached by 2030.

However, funding remains a major constraint: most countries lack adequate financial resources to fund key hepatitis services.

Diagnosis challenge

To achieve rapid scale-up of treatment, countries need urgently to increase uptake of testing and diagnosis for hepatitis B and C. As of 2015, an estimated 1 in 10 people living with hepatitis B, and 1 in 5 people living with hepatitis C, were aware of their infection. Countries need to improve policies, and programmes to increase awareness and subsequent diagnosis.

Prevention gaps

Countries need to provide a full range of hepatitis prevention services that are accessible to different population groups, particularly those at greater risk.

Largely due to increases in the uptake of hepatitis B vaccine, hepatitis B infection rates in children under 5 fell to 1.3% in 2015, from 4.7% in the pre-vaccine era.

However, the delivery of other prevention services, such as birth-dose vaccination for hepatitis B, harm reduction services for people who inject drugs, and infection control in many health services, remains low. This has led to continuing rates of new infections, including 1.75 million new hepatitis C cases every year.

Need for innovation

Innovation in many aspects of the hepatitis response must continue. New tools required include a functional cure for hepatitis B infection and the development of more effective point-of-care diagnostic tools for both hepatitis B and C.

“We cannot meet the ambitious hepatitis elimination targets without innovation in prevention interventions and approaches, and implementing them to scale,” said Dr Ren Minghui Assistant Director-General for Communicable Diseases, WHO. “The great successes of hepatitis B vaccination programmes in many countries need to be replicated and sustained globally in the context of moving forward to universal health coverage.”

Implementation of elimination strategy

The World Hepatitis Summit 2017 will be attended by over 900 delegates from more than 100 countries, including Ministers of Health, national programme managers, and representatives from organizations of people affected by viral hepatitis. The Summit will review progress and renew commitments by global partners to achieve the elimination of viral hepatitis by 2030 – a target reflected in WHO’s elimination strategy and the UN Sustainable Development Goals.

For more information, please contact:

Tunga Namjilsuren

WHO Communications Officer

Mobile: +41 79 203 3176

Email: namjilsurent@who.int

Pru Smith

WHO Communications Officer

Mobile: +41 79 477 1744

Email: smithp@who.int

Tara Farrell

World Hepatitis Alliance

Telephone: +44 20 7378 0159

Email: Tara.farrell@worldhepatitisalliance.org

Grace Perpétuo

Government of Brazil, Ministry of Health

Telephone: +55 61 99968 6541

Email: grace.perpetuo@aids.gov.br

CDC recommendations to healthcare providers treating patients in Puerto Rico and USVI, as well as those treating patients in the continental US who recently traveled in hurricane-affected areas during the period of September 2017 – March 2018.

Wednesday, October 25th, 2017Advice for Providers Treating Patients in or Recently Returned from Hurricane-Affected Areas, Including Puerto Rico and US Virgin Islands

Distributed via the CDC Health Alert Network

October 24, 2017, 1330 ET (1:30 PM ET)

CDCHAN-00408

Summary

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) is working with federal, state, territorial, and local agencies and global health partners in response to recent hurricanes. CDC is aware of media reports and anecdotal accounts of various infectious diseases in hurricane-affected areas, including Puerto Rico and the US Virgin Islands (USVI). Because of compromised drinking water and decreased access to safe water, food, and shelter, the conditions for outbreaks of infectious diseases exist.

The purpose of this HAN advisory is to remind clinicians assessing patients currently in or recently returned from hurricane-affected areas to be vigilant in looking for certain infectious diseases, including leptospirosis, dengue, hepatitis A, typhoid fever, vibriosis, and influenza. Additionally, this Advisory provides guidance to state and territorial health departments on enhanced disease reporting.

Background

Hurricanes Irma and Maria made landfall in Puerto Rico and USVI in September 2017, causing widespread flooding and devastation. Natural hazards associated with the storms continue to affect many areas. Infectious disease outbreaks of diarrheal and respiratory illnesses can occur when access to safe water and sewage systems are disrupted and personal hygiene is difficult to maintain. Additionally, vector borne diseases can occur due to increased mosquito breeding in standing water; both Puerto Rico and USVI are at risk for outbreaks of dengue, Zika, and chikungunya.

Health care providers and public health practitioners should be aware that post-hurricane environmental conditions may pose an increased risk for the spread of infectious diseases among patients in or recently returned from hurricane-affected areas; including leptospirosis, dengue, hepatitis A, typhoid fever, vibriosis, and influenza. The period of heightened risk may last through March 2018, based on current predictions of full restoration of power and safe water systems in Puerto Rico and USVI.

In addition, providers in health care facilities that have experienced water damage or contaminated water systems should be aware of the potential for increased risk of infections in those facilities due to invasive fungi, nontuberculous Mycobacterium species, Legionella species, and other Gram-negative bacteria associated with water (e.g., Pseudomonas), especially among critically ill or immunocompromised patients.

Cholera has not occurred in Puerto Rico or USVI in many decades and is not expected to occur post-hurricane.

Recommendations

These recommendations apply to healthcare providers treating patients in Puerto Rico and USVI, as well as those treating patients in the continental US who recently traveled in hurricane-affected areas (e.g., within the past 4 weeks), during the period of September 2017 – March 2018.

- Health care providers and public health practitioners in hurricane-affected areas should look for community and healthcare-associated infectious diseases.

- Health care providers in the continental US are encouraged to ask patients about recent travel (e.g., within the past 4 weeks) to hurricane-affected areas.

- All healthcare providers should consider less common infectious disease etiologies in patients presenting with evidence of acute respiratory illness, gastroenteritis, renal or hepatic failure, wound infection, or other febrile illness. Some particularly important infectious diseases to consider include leptospirosis, dengue, hepatitis A, typhoid fever, vibriosis, and influenza.

- In the context of limited laboratory resources in hurricane-affected areas, health care providers should contact their territorial or state health department if they need assistance with ordering specific diagnostic tests.

- For certain conditions, such as leptospirosis, empiric therapy should be considered pending results of diagnostic tests— treatment for leptospirosis is most effective when initiated early in the disease process. Providers can contact their territorial or state health department or CDC for consultation.

- Local health care providers are strongly encouraged to report patients for whom there is a high level of suspicion for leptospirosis, dengue, hepatitis A, typhoid, and vibriosis to their local health authorities, while awaiting laboratory confirmation.

- Confirmed cases of leptospirosis, dengue, hepatitis A, typhoid fever, and vibriosis should be immediately reported to the territorial or state health department to facilitate public health investigation and, as appropriate, mitigate the risk of local transmission. While some of these conditions are not listed as reportable conditions in all states, they are conditions of public health importance and should be reported.

For More Information

- General health information about hurricanes and other tropical storms: https://www.cdc.gov/disasters/hurricanes/index.html

- Information about Hurricane Maria: https://www.cdc.gov/disasters/hurricanes/hurricane_maria.html

- Information for Travelers:

- Travel notice for Hurricanes Irma and Maria in the Caribbean: https://wwwnc.cdc.gov/travel/notices/alert/hurricane-irma-in-the-caribbean

- Health advice for travelers to Puerto Rico: https://wwwnc.cdc.gov/travel/destinations/traveler/none/puerto-rico?s_cid=ncezid-dgmq-travel-single-001

- Health advice for travelers to the U.S. Virgin Islands: https://wwwnc.cdc.gov/travel/destinations/traveler/none/usvirgin-islands?s_cid=ncezid-dgmq-travel-leftnav-traveler

- Resources from CDC Health Information for International Travel 2018 (the Yellow Book):

- Post-travel Evaluation: https://wwwnc.cdc.gov/travel/yellowbook/2018/post-travel-evaluation/general-approach-to-the-returned-traveler

- Information about infectious diseases after a disaster: https://www.cdc.gov/disasters/disease/infectious.html

- Dengue: https://www.cdc.gov/dengue/index.html

- Hepatitis A: https://www.cdc.gov/hepatitis/HAV/index.htm

- Leptospirosis: https://www.cdc.gov/leptospirosis/

- Typhoid fever: https://www.cdc.gov/typhoid-fever/index.html

- Vibriosis: https://www.cdc.gov/vibrio/index.html

- Information about other infectious diseases of concern:

- Conjunctivitis: https://www.cdc.gov/conjunctivitis/

- Influenza: https://www.cdc.gov/flu/index.htm

- Scabies: https://www.cdc.gov/parasites/scabies/index.html

- Tetanus and wound management: https://www.cdc.gov/disasters/emergwoundhcp.html

- Tetanus in Areas Affected by a Hurricane: Guidelines for Clinicians https://emergency.cdc.gov/coca/cocanow/2017/2017sept12.asp

World Hepatitis Day

Friday, July 28th, 2017Eliminate hepatitis: WHO

27 July 2017 | GENEVA – New WHO data from 28 countries – representing approximately 70% of the global hepatitis burden – indicate that efforts to eliminate hepatitis are gaining momentum. Published to coincide with World Hepatitis Day, the data reveal that nearly all 28 countries have established high-level national hepatitis elimination committees (with plans and targets in place) and more than half have allocated dedicated funding for hepatitis responses.

On World Hepatitis Day, WHO is calling on countries to continue to translate their commitments into increased services to eliminate hepatitis. This week, WHO has also added a new generic treatment to its list of WHO-prequalified hepatitis C medicines to increase access to therapy, and is promoting prevention through injection safety: a key factor in reducing hepatitis B and C transmission.

From commitment to Action

“It is encouraging to see countries turning commitment into action to tackle hepatitis.” said Dr Tedros Adhanom Ghebreyesus, WHO Director-General. “Identifying interventions that have a high impact is a key step towards eliminating this devastating disease. Many countries have succeeded in scaling-up the hepatitis B vaccination. Now we need to push harder to increase access to diagnosis and treatment.”

World Hepatitis Day 2017 is being commemorated under the theme “Eliminate Hepatitis” to mobilize intensified action towards the health targets in the 2030 Sustainable Development Goals. In 2016, the World Health Assembly endorsed WHO’s first global health sectors strategy on viral hepatitis to help countries scale up their responses.

The new WHO data show that more than 86% of countries reviewed have set national hepatitis elimination targets and more than 70% have begun to develop national hepatitis plans to enable access to effective prevention, diagnosis, treatment and care services. Furthermore, nearly half of the countries surveyed are aiming for elimination through providing universal access to hepatitis treatment. But WHO is concerned that progress needs to speed up.

“The national response towards hepatitis elimination is gaining momentum. However, at best one in ten people who are living with hepatitis know they are infected and can access treatment. This is unacceptable,” said Dr Gottfried Hirnschall, WHO’s Director of the HIV Department and Global Hepatitis Programme.

“For hepatitis elimination to become a reality, countries need to accelerate their efforts and increase investments in life-saving care. There is simply no reason why many millions of people still have not been tested for hepatitis and cannot access the treatment for which they are in dire need.”

Viral hepatitis affected 325 million people worldwide in 2015, with 257 million people living with hepatitis B and 71 million people living with hepatitis C – the two main killers of the five types of hepatitis. Viral hepatitis caused 1.34 million deaths in 2015 – a figure close to the number of TB deaths and exceeding deaths linked to HIV.

Improving access to hepatitis C cure

Hepatitis C can be completely cured with direct acting antivirals (DAAs) within 3 months. However, as of 2015, only 7% of the 71 million people with chronic hepatitis C had access to treatment.

WHO is working to ensure that DAAs are affordable and accessible to those who need them. Prices have dropped dramatically in some countries (primarily in some high-burden, low-and lower middle income countries), facilitated by the introduction of generic versions of these medicines. The list of DAAs available to countries for treating hepatitis C is growing.

WHO has just prequalified the first generic version of one of these drugs: sofosbuvir. The average price of the required three-month treatment course of this generic is between US$260 and US$280, a small fraction of the original cost of the medicine when it first went on the market in 2013. WHO prequalification guarantees a product’s quality, safety and efficacy and means it can now be procured by the United Nations and financing agencies such as UNITAID, which now includes medicines for people living with HIV who also have hepatitis C in the portfolio of conditions it covers.

Hepatitis B treatment

With high morbidity and mortality globally, there is great interest also in the development of new therapies for chronic hepatitis B virus infection. The most effective current hepatitis B treatment, tenofovir, (which is not curative and which in most cases needs to be taken for life), is available for as low as $48 per year in many low and middle income countries. There is also an urgent need to scale up access to hepatitis B testing.

Improving injection safety and infection prevention to reduce new cases of hepatitis B and C

Use of contaminated injection equipment in health-care settings accounts for a large number of new HCV and HBV infections worldwide, making injection safety an important strategy.Others include preventing transmission through invasive procedures, such as surgery and dental care; increasing hepatitis B vaccination rates and scaling up harm reduction programmes for people who inject drugs.

Today WHO is launching a range of new educational and communication tools to support a campaign entitled “Get the Point-Make smart injection choices” to improve injection safety in order to prevent hepatitis and other bloodborne infections in health-care settings.

World Hepatitis Summit

World Hepatitis Summit 2017, 1–3 November in São Paulo, Brazil, promises to be the largest global event to advance the viral hepatitis agenda, bringing together key players to accelerate the global response. Organised jointly by WHO, the World Hepatitis Alliance (WHA) and the Government of Brazil, the theme of the Summit is “Implementing the Global health sector strategy on viral hepatitis: towards the elimination of hepatitis as a public health threat”.

For more information, please contact:

Pru Smith

Communications Officer

Telephone: +41 22 791 4586

Mobile: +41 794 771 744

E-mail: smithp@who.int

Tunga (Oyuntungalag) Namjilsuren

Information Manager

WHO Department of HIV, Global Hepatitis Programme

Mobile: +41 79 203 3176

Email: namjilsurent@who.int