Archive for the ‘Chagas Disease’ Category

Identification of a Triatoma sanguisuga “Kissing Bug” — Delaware, 2018

Thursday, April 25th, 2019Eggers P, Offutt-Powell TN, Lopez K, Montgomery SP, Lawrence GG. Notes from the Field: Identification of a Triatoma sanguisuga “Kissing Bug” — Delaware, 2018. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2019;68:359. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.15585/mmwr.mm6815a5External.

“……Subsequently, the insect was sent to CDC, where species-level identification was morphologically confirmed. Conventional polymerase chain reaction testing of the triatomine hindgut was negative for T. cruzi. Bloodmeal analysis detected a human bloodmeal; the girl who was bitten had no ill effects.

This finding represents the first confirmed identification of T. sanguisuga in Delaware…..

Chagas disease can cause serious cardiac and gastrointestinal complications. CDC estimates that approximately 300,000 persons with Chagas disease live in the United States, and most were infected with T. cruzi in the parts of Latin America where Chagas disease is found. Triatomine bugs also are found in the United States, but only a few cases of Chagas disease from contact with the bugs have been documented in this country (2). Although presence of the vector has been confirmed in Delaware, there is no current evidence of T. cruzi in the state (2). T. cruzi is a zoonotic parasite that infects many mammal species and is found throughout the southern half of the United States (2). Even where T. cruzi is circulating, not all triatomine bugs are infected with the parasite. The likelihood of human T. cruzi infection from contact with a triatomine bug in the United States is low, even when the bug is infected (2).

Precautions to prevent house triatomine bug infestation include locating outdoor lights away from dwellings such as homes, dog kennels, and chicken coops and turning off lights that are not in use. Home owners should also remove trash, wood, and rock piles from around the home and clear out any bird and animal nests from around the home. Cracks and gaps around windows, air conditioners, walls, roofs, doors, and crawl spaces into the house should be inspected and sealed. Chimney flues should be tightly closed when not in use and screens should be used on all doors and windows. Ideally, pets should sleep indoors, especially at night, and outdoor pet resting areas kept clean. Finally, homeowners might consider using a licensed pest control professional for insect control (1,2)……”

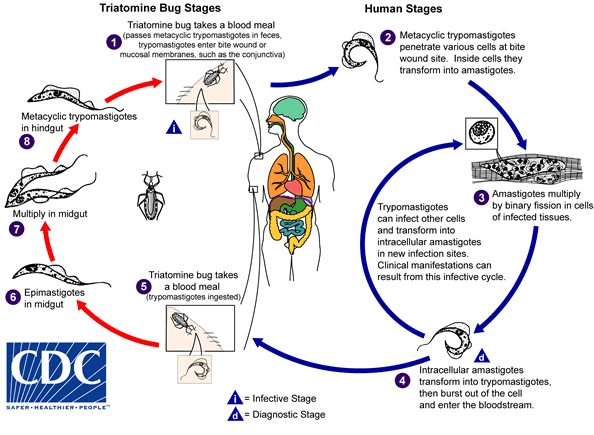

An infected triatomine insect vector (or “kissing bug”) takes a blood meal and releases trypomastigotes in its feces near the site of the bite wound. Trypomastigotes enter the host through the wound or through intact mucosal membranes, such as the conjunctiva  . Common triatomine vector species for trypanosomiasis belong to the genera Triatoma, Rhodnius, and Panstrongylus. Inside the host, the trypomastigotes invade cells near the site of inoculation, where they differentiate into intracellular amastigotes

. Common triatomine vector species for trypanosomiasis belong to the genera Triatoma, Rhodnius, and Panstrongylus. Inside the host, the trypomastigotes invade cells near the site of inoculation, where they differentiate into intracellular amastigotes  . The amastigotes multiply by binary fission

. The amastigotes multiply by binary fission  and differentiate into trypomastigotes, and then are released into the circulation as bloodstream trypomastigotes

and differentiate into trypomastigotes, and then are released into the circulation as bloodstream trypomastigotes  . Trypomastigotes infect cells from a variety of tissues and transform into intracellular amastigotes in new infection sites. Clinical manifestations can result from this infective cycle. The bloodstream trypomastigotes do not replicate (different from the African trypanosomes). Replication resumes only when the parasites enter another cell or are ingested by another vector. The “kissing bug” becomes infected by feeding on human or animal blood that contains circulating parasites

. Trypomastigotes infect cells from a variety of tissues and transform into intracellular amastigotes in new infection sites. Clinical manifestations can result from this infective cycle. The bloodstream trypomastigotes do not replicate (different from the African trypanosomes). Replication resumes only when the parasites enter another cell or are ingested by another vector. The “kissing bug” becomes infected by feeding on human or animal blood that contains circulating parasites  . The ingested trypomastigotes transform into epimastigotes in the vector’s midgut

. The ingested trypomastigotes transform into epimastigotes in the vector’s midgut  . The parasites multiply and differentiate in the midgut

. The parasites multiply and differentiate in the midgut  and differentiate into infective metacyclic trypomastigotes in the hindgut

and differentiate into infective metacyclic trypomastigotes in the hindgut  .

.

Trypanosoma cruzi can also be transmitted through blood transfusions, organ transplantation, transplacentally (from mother to unborn baby), and in laboratory accidents.

Brazil: 14 confirmed Chagas disease cases after a family drank the juice of the bacaba, a type of palm tree from the Amazon.

Tuesday, December 18th, 2018

“…..The suspicion is that feces of the barbeque beetle, which transmits the disease, have gone into the juice…..”

Infection can also occur from:

- mother-to-baby (congenital),

- contaminated blood products (transfusions),

- an organ transplanted from an infected donor,

- laboratory accident, or

- contaminated food or drink (rare)

Chagas disease has an acute and a chronic phase. If untreated, infection is lifelong.

Acute Chagas disease occurs immediately after infection, may last up to a few weeks or months, and parasites may be found in the circulating blood. Infection may be mild or asymptomatic. There may be fever or swelling around the site of inoculation (where the parasite entered into the skin or mucous membrane). Rarely, acute infection may result in severe inflammation of the heart muscle or the brain and lining around the brain.

Following the acute phase, most infected people enter into a prolonged asymptomatic form of disease (called “chronic indeterminate”) during which few or no parasites are found in the blood. During this time, most people are unaware of their infection. Many people may remain asymptomatic for life and never develop Chagas-related symptoms. However, an estimated 20 – 30% of infected people will develop debilitating and sometimes life-threatening medical problems over the course of their lives.

Complications of chronic Chagas disease may include:

- heart rhythm abnormalities that can cause sudden death;

- a dilated heart that doesn’t pump blood well;

- a dilated esophagus or colon, leading to difficulties with eating or passing stool.

In people who have suppressed immune systems (for example, due to AIDS or chemotherapy), Chagas disease can reactivate with parasites found in the circulating blood. This occurrence can potentially cause severe disease.

Romaña’s sign, the swelling of the child’s eyelid, is a marker of acute Chagas disease. The swelling is due to bug feces being accidentally rubbed into the eye, or because the bite wound was on the same side of the child’s face as the swelling. Photo courtesy of WHO/TDR

Congenitally acquired Chagas disease reported in Canada

Wednesday, December 20th, 2017The U.S. FDA today granted accelerated approval to benznidazole for use in children ages 2 to 12 years old with Chagas disease — the first treatment approved in the United States for the treatment of Chagas disease.

Wednesday, August 30th, 2017The U.S. Food and Drug Administration today granted accelerated approval to benznidazole for use in children ages 2 to 12 years old with Chagas disease. It is the first treatment approved in the United States for the treatment of Chagas disease.

Chagas disease, or American trypanosomiasis, is a parasitic infection caused by Trypanosoma cruzi and can be transmitted through different routes, including contact with the feces of a certain insect, blood transfusions, or from a mother to her child during pregnancy. After years of infection, the disease can cause serious heart illness, and it also can affect swallowing and digestion. While Chagas disease primarily affects people living in rural parts of Latin America, recent estimates are that there may be approximately 300,000 persons in the United States with Chagas disease.

“The FDA is committed to making available safe and effective therapeutic options to treat tropical diseases,” said Edward Cox, M.D., director of the Office of Antimicrobial Products in the FDA’s Center for Drug Evaluation and Research.

The safety and efficacy of benznidazole were established in two placebo-controlled clinical trials in pediatric patients 6 to 12 years old. In the first trial, approximately 60 percent of children treated with benznidazole had an antibody test change from positive to negative compared with approximately 14 percent of children who received a placebo. Results in the second trial were similar: Approximately 55 percent of children treated with benznidazole had an antibody test change from positive to negative compared with 5 percent who received a placebo. An additional study of the safety and pharmacokinetics (how the body absorbs, distributes and clears the drug) of benznidazole in pediatric patients 2 to 12 years of age provided information for dosing recommendations down to 2 years of age.

The most common adverse reactions in patients taking benznidazole were stomach pain, rash, decreased weight, headache, nausea, vomiting, abnormal white blood cell count, urticaria (hives), pruritus (itching) and decreased appetite. Benznidazole is associated with serious risks including serious skin reactions, nervous system effects and bone marrow depression. Based on findings from animal studies, benznidazole could cause fetal harm when administered to a pregnant woman.

Benznidazole was approved using the Accelerated Approval pathway. The Accelerated Approval pathway allows the FDA to approve drugs for serious conditions where there is unmet medical need and adequate and well-controlled trials establish that the drug has an effect on a surrogate endpoint that is reasonably likely to predict a clinical benefit to patients. Further study is required to verify and describe the anticipated clinical benefit of benznidazole.

The FDA granted benznidazole priority review and orphan product designation. These designations were granted because Chagas disease is a rare disease, and until now, there were no approved drugs for Chagas disease in the United States.

With this approval, benznidazole’s manufacturer, Chemo Research, S. L., is awarded a Tropical Disease Priority Review Voucher in accordance with a provision included in the Food and Drug Administration Amendments Act of 2007 that aims to encourage development of new drugs and biological products for the prevention and treatment of certain tropical diseases.

The FDA, an agency within the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, protects the public health by assuring the safety, effectiveness, and security of human and veterinary drugs, vaccines and other biological products for human use, and medical devices. The agency also is responsible for the safety and security of our nation’s food supply, cosmetics, dietary supplements, products that give off electronic radiation, and for regulating tobacco products.

###

<!–

–>

CDC’s Emergency Drugs for US Clinicians and Hospitals

Thursday, June 8th, 2017Our Formulary

The following information is provided as an informational resource for guidance only. It is not intended as a substitute for professional judgment. These highlights and any hyperlinks may not include all the information needed to use each respective drug or biologic safely and effectively. See full prescribing information (package insert) or IND protocol for each respective drug or biologic, which accompany the product when it is delivered to the treating physician and/or pharmacist.

The Drug Service formulary is subject to change based on current public health needs, updates to treatment guidelines, and/or drug availability. For historical reference, we have included products no longer supplied by the Drug Service.

| Product & Supplier | Indication & Eligibility | How Supplied |

|---|---|---|

| Anthrax Vaccine Absorbed

(Also known as “AVA”; BioThrax®, Emergent BioSolutions) |

For the active immunization for the prevention of disease caused by Bacillus anthracis, in persons 18 through 65 years of age at high risk for exposure

Because the risk for anthrax infection in the general population is low, routine immunization is not recommended The safety and efficacy of BioThrax® in a post-exposure setting have not been established. |

Suspension for injection in 5 mL multidose vials, each containing 10 doses |

| Artesunate, intravenous

(Supplied to CDC by the Walter Reed Army Institute of Research) |

For the treatment of severe malaria in patients who require parenteral (IV) therapy

Patient must meet the eligibility criteria in the IND protocol |

110 mg; sterile dry-filled powder with phosphate buffer diluent for reconstitution |

| Benznidazole

(Benznidazol, Manufactured by LAFEPE) |

For the treatment of American trypanosomiasis (Chagas disease)

Patient must meet the eligibility criteria in the IND protocol |

100 mg double-scored tablet

12.5 mg dispersible tablet for pediatric use |

| Botulism Antitoxin Heptavalent (Equine), Types A-G

(Also known as “HBAT”; Manufactured by Cangene Corp. – BAT™) |

For the treatment of symptomatic botulism following documented or suspected exposure to botulinum neurotoxin | 20 mL or 50 mL single-use glass vial

May be received frozen or thawed |

| Diethylcarbamazine

(Also known as “DEC”; Supplied to CDC by the World Health Organization; Manufactured by E.I.P.I.C.O.) |

For the treatment of certain filarial diseases, including lymphatic filariasis caused by infection with Wuchereria bancrofti, Brugia malayi, or Brugia timori; tropical pulmonary eosinophilia; and loiasis

For prophylactic use in persons determined to be at increased risk for Loa loa infection Patient must meet the eligibility criteria in the IND protocol |

100 mg tablet |

| Diphtheria Antitoxin (Equine)

(Also known as “DAT”; Manufactured by Instituto Butantan) |

For prevention or treatment of actual or suspected cases of diphtheria

Patient must meet the eligibility criteria in the IND protocol |

1 mL single-use ampule containing 10,000 units |

| Eflornithine

(Also known as “DFMO”; Supplied to CDC by the World Health Organization; Manufactured by Sanofi Aventis – Ornidyl®) |

For the treatment of second-stage African trypanosomiasis (sleeping sickness) caused by Trypanosoma brucei gambiense, with involvement of the central nervous system | 20 g/100 mL hypertonic solution for IV infusion

Must be diluted with Sterile Water for Injection before use |

| Melarsoprol

(Supplied to CDC by the World Health Organization; Manufactured by Sanofi Aventis – Arsobal®) |

For the treatment of second-stage African trypanosomiasis (sleeping sickness), with involvement of the central nervous system

Patient must meet the eligibility criteria in the IND protocol |

5 mL glass ampule containing 180 mg/5 mL (36 mg/mL) |

| Nifurtimox

(Supplied to CDC by the World Health Organization; Manufactured by Bayer – Lampit®) |

For the treatment of American trypanosomiasis (Chagas disease)

Patient must meet the eligibility criteria in the IND protocol |

120 mg double-scored tablet |

| Sodium Stibogluconate

(Manufactured by GlaxoSmithKline, UK – Pentostam®) |

For the treatment of leishmaniasis

Patient must meet the eligibility criteria in the IND protocol |

Solution for injection in 100 mL multidose bottle

100 mg pentavalent antimony (Sb) per mL |

| Suramin

(Supplied to CDC by the World Health Organization; Manufactured by Bayer – Germanin) |

For the treatment of first-stage African trypanosomiasis (sleeping sickness) caused by Trypanosoma brucei rhodesiense, without involvement of the central nervous system

Patient must meet the eligibility criteria in the IND protocol |

1 gram of suramin for injection in a 10 mL vial (100 mg/mL solution of suramin sodium)

Must be reconstituted with 10 mL Sterile Water for Injection before use |

| Vaccinia Vaccine

(Also known as the “Smallpox Vaccine”; Manufactured by Sanofi Aventis – ACAM2000®) |

For active immunization against smallpox disease for persons determined to be at high risk for smallpox infection | Lyophilized powder reconstituted with diluent (provided)

Contains 100 doses per vial |

Anthrax Vaccine Adsorbed

Anthrax Vaccine Adsorbed (AVA) is indicated for the active immunization for the prevention of disease caused by Bacillus anthracis, in persons 18 through 65 years of age at high risk for exposure. The safety and efficacy of AVA in a post-exposure setting have not been established.

CDC provides anthrax vaccine for laboratory workers conducting research under federally funded projects who require preexposure vaccination based on their occupational risk.

Preexposure vaccination is recommended for laboratorians at risk for repeated exposure to fully virulent B. anthracis spores, such as those who 1) work with high concentrations of spores with potential for aerosol production; 2) handle environmental samples that might contain powders and are associated with anthrax investigations; 3) routinely work with pure cultures of B. anthracis; 4) frequently work in spore-contaminated areas after a bioterrorism attack; or 5) work in other settings where repeated exposures to B. anthracis aerosols may occur. Read more[PDF – 36 pages](https://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/pdf/rr/rr5906.pdf).

More Information for Clinicians

CDC’s Anthrax Vaccination Website

Educational Toolkit for Clinicians (from Department of Defense Anthrax Immunization Program)

Full Prescribing Information for BioThrax®

How to Request

Anthrax vaccine must be administered by or under the supervision of the physician who registers with CDC.

Contact the CDC Drug Service for more information.

Artesunate, Intravenous

Artesunate is in the class of medications known as artemesinins, which are derivatives from the “qinghaosu” or sweet wormwood plant (Artemisia annua). Artesunate is not currently licensed by FDA but is made available in the United States under a CDC-sponsored IND protocol for treatment of documented cases of severe malaria(https://www.cdc.gov/malaria/about/index.html) that require parenteral therapy. Read more(https://www.cdc.gov/malaria/diagnosis_treatment/artesunate.html).

More Information for Clinicians

Diagnostic assistance for malaria is available through DPDx.

How to Request

Clinicians who wish to obtain artesunate for severe malaria should contact the CDC Malaria Hotline at 770-488-7788 (M-F, 8am-4:30pm, Eastern time) or, after hours, the CDC Emergency Operations Center (EOC) at 770-488-7100, and request to speak with a CDC Malaria Branch clinician. A Malaria Branch clinician will provide clinical consultation by telephone and, if indicated, authorize the emergency release of artesunate from one of the CDC Quarantine Stations located in major airports around the nation, ensuring delivery to any location in the United States within hours.

Requests for unapproved uses cannot be granted.

For non-emergency questions related to artesunate IV, contact the CDC Drug Service.

Benznidazole

Benznidazole is a 2-nitroimidazole trypanocidal agent that was introduced in 1971 for the treatment of Trypanosoma cruzi infection—i.e., Chagas disease, also known as American trypanosomiasis(https://www.cdc.gov/parasites/chagas/). Benznidazole is one of two drugs available from CDC for the treatment of Chagas disease (the other is nifurtimox). In the United States, the need to have drugs available for treating Chagas disease has been increasing, largely because of implementation of T. cruzi blood-donor screening in 2007, which has identified chronically infected persons (mainly Latin American immigrants) who might benefit from treatment and has heightened awareness of Chagas disease.

More Information for Clinicians

Diagnostic assistance for American trypanosomiasis is available through DPDx.

How to Request

Contact the CDC Drug Service for more information.

Questions regarding treatment of Chagas disease should be directed to CDC Parasitic Diseases Inquiries (404-718-4745; email chagas@cdc.gov) M-F 7:30am-4pm EST.

For emergencies (for example, acute Chagas disease with severe manifestations, Chagas disease in a newborn, or Chagas disease in an immunocompromised person) outside of regular business hours, call the CDC Emergency Operations Center (770-488-7100) and ask for the person on call for Parasitic Diseases.

Botulism Antitoxin Heptavalent (Equine), Types A-G

Botulism Antitoxin Heptavalent (HBAT) contains equine-derived antibody to the seven known botulinum toxin types (A-G). HBAT is composed of <2% intact immunoglobulin G (IgG) and ≥90% Fab and F(ab’)2 immunoglobulin fragments. These fragments are created by the enzymatic cleavage and removal of Fc immunoglobulin components in a process sometimes referred to as despeciation. HBAT is supplied on an emergency basis for the treatment of persons thought to be suffering from botulism and works by neutralizing unbound toxin molecules. In 2010, HBAT became the only botulism antitoxin available in the United States for naturally occurring non-infant botulism.

It is available only from CDC because of its limited use and its relatively short expiration date. The antitoxin is stored at CDC Quarantine Stations located in major airports around the nation, ensuring delivery to any location in the United States within hours.

BabyBIG® (botulism immune globulin) remains available for infant botulism through the California Infant Botulism Treatment and Prevention Program.

More Information for Clinicians

How to Request

Clinicians who suspect a diagnosis of botulism in a patient should immediately call their state health department’s 24-hour telephone number(https://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/international/relres.html) to maintain effective botulism surveillance and to facilitate rapid detection of outbreaks. The state health department will contact CDC to arrange for a clinical consultation by telephone and, if indicated, release of botulism antitoxin. State health departments requesting botulism antitoxin should contact the CDC Emergency Operations Center (EOC) at 770-488-7100. Read more(https://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/preview/mmwrhtml/mm5232a8.htm).

For non-emergency questions concerning botulism antitoxin, contact the CDC Drug Service.

Diethylcarbamazine (DEC)

DEC is an antihelminthic agent used for treatment of lymphatic filariasis (caused by infection with Wuchereria bancrofti, Brugia malayi, or Brugia timori), tropical pulmonary eosinophilia, and loiasis(https://www.cdc.gov/parasites/loiasis/); DEC also has prophylactic benefit for Loa loa infection. DEC has been used worldwide for more than 50 years. In the past, Wyeth-Ayerst Laboratories made DEC available as a licensed drug; in the late 1990s, because of unavailability of a bulk chemical supplier, Wyeth-Ayerst discontinued distribution of DEC in the United States.

More Information for Clinicians

Diagnostic assistance for filarial diseases is available through DPDx.

How to Request

Contact the CDC Drug Service for more information.

Questions regarding treatment of filarial diseases should be directed to CDC Parasitic Diseases Inquiries (404-718-4745; email parasites@cdc.gov) M-F 7:30am-4pm EST.

After-hours emergencies: 1-770-488-7100

Diphtheria Antitoxin (Equine)

Diphtheria antitoxin (DAT) is used to prevent or treat diphtheria by neutralizing the toxins produced by Corynebacterium diphtheriae. DAT is a sterile, aqueous solution of the refined and concentrated proteins, chiefly globulins, containing antibodies obtained from the serum of horses that have been immunized against diphtheria toxin. DAT is available under an IND protocol sponsored by CDC and is released only for actual or suspected cases of diphtheria(https://www.cdc.gov/diphtheria/about/index.html). The antitoxin is stored at CDC Quarantine Stations located in major airports around the nation, ensuring delivery to any location in the United States within hours.

More Information for Clinicians

CDC’s Vaccine-Related Topics: Diphtheria Antitoxin(https://www.cdc.gov/diphtheria/dat.html)

How to Request

Clinicians who suspect a diagnosis of respiratory diphtheria can obtain DAT by contacting the Emergency Operations Center at 770-488-7100. They will be connected with the diphtheria duty officer, who will provide clinical consultation and, if indicated, initiate the release of diphtheria antitoxin.

For non-emergency questions concerning diphtheria antitoxin, contact the CDC Drug Service.

Eflornithine

Eflornithine is an antitrypanosomal agent that inhibits the enzyme ornithine decarboxylase. Antitrypanosomal treatment is indicated for all persons diagnosed with African trypanosomiasis (sleeping sickness)(https://www.cdc.gov/parasites/sleepingsickness/); the choice of therapy depends on the infecting subspecies of the parasite and on the stage of the infection. Eflornithine is considered the drug of choice for the treatment of second-stage Trypanosoma brucei gambiense (West African) infection, with involvement of the central nervous system. It is not effective against T. b. rhodesiense (East African) infection (see melarsoprol). Although the manufacturer, Aventis, maintains its US licensure, eflornithine is not commercially available in the United States.

More Information for Clinicians

Human African trypanosomiasis, WHO

Diagnostic assistance for African trypanosomiasis is available through DPDx.

How to Request

Contact the CDC Drug Service for more information.

Questions regarding treatment of African trypanosomiasis should be directed to CDC Parasitic Diseases Inquiries (404-718-4745; email parasites@cdc.gov) M-F 7:30am-4pm EST.

For emergencies outside of regular business hours, call the CDC Emergency Operations Center (770-488-7100) and ask for the person on call for Parasitic Diseases.

Melarsoprol

Melarsoprol is an organoarsenic compound with trypanocidal effects that has been used outside the United States since 1949. Antitrypanosomal treatment is indicated for all persons diagnosed with African trypanosomiasis (sleeping sickness)(https://www.cdc.gov/parasites/sleepingsickness/); the choice of therapy depends on the infecting subspecies of the parasite and on the stage of the infection. Melarsoprol is used for the treatment of second-stage infection (involving the central nervous system). It is the only available therapy for second-stage Trypanosoma brucei rhodesiense (East African) infection, whereas eflornithine typically is used for second-stage T. b. gambiense (West African) infection.

More Information for Clinicians

Human African trypanosomiasis, WHO

Diagnostic assistance for African trypanosomiasis is available through DPDx.

How to Request

Contact the CDC Drug Service for more information.

Questions regarding treatment of African trypanosomiasis should be directed to CDC Parasitic Diseases Inquiries (404-718-4745; email parasites@cdc.gov) M-F 7:30am-4pm EST.

For emergencies outside of regular business hours, call the CDC Emergency Operations Center (770-488-7100) and ask for the person on call for Parasitic Diseases.

Nifurtimox

Nifurtimox is a nitrofuran analog that was introduced in 1965 for the treatment of Trypanosoma cruzi infection—i.e., Chagas disease, also known as American trypanosomiasis(https://www.cdc.gov/parasites/chagas/). Nifurtimox is one of two drugs available from CDC for the treatment of Chagas disease (the other is benznidazole). In the United States, the need to have drugs available for treating Chagas disease has been increasing, largely because of implementation of T. cruzi blood-donor screening in 2007, which has identified chronically infected persons (mainly Latin American immigrants) who might benefit from treatment and has heightened awareness of Chagas disease.

More Information for Clinicians

Diagnostic assistance for American trypanosomiasis is available through DPDx.

How to Request

Contact the CDC Drug Service for more information.

Questions regarding treatment of Chagas disease should be directed to CDC Parasitic Diseases Inquiries (404-718-4745; email chagas@cdc.gov) M-F 7:30am-4pm EST.

For emergencies (for example, acute Chagas disease with severe manifestations, Chagas disease in a newborn, or Chagas disease in an immunocompromised person) outside of regular business hours, call the CDC Emergency Operations Center (770-488-7100) and ask for the person on call for Parasitic Diseases.

Sodium Stibogluconate

Sodium stibogluconate (Pentostam®) is a pentavalent antimony compound used for treatment of leishmaniasis(https://www.cdc.gov/parasites/leishmaniasis). The three main clinical syndromes in humans are visceral, cutaneous, and mucosal leishmaniasis. Pentostam is a well-established antileishmanial agent that has been used in many countries of the world for more than half a century.

More Information for Clinicians

Diagnostic assistance for leishmaniasis is available through DPDx.

How to Request

Contact the CDC Drug Service for more information.

Questions regarding treatment of leishmaniasis should be directed to CDC Parasitic Diseases Inquiries (404-718-4745; email parasites@cdc.gov) M-F 7:30am-4pm EST.

After-hours emergencies: 1-770-488-7100

Suramin

Suramin is a negatively charged, high-molecular-weight sulfated naphthylamine. It was introduced in the 1920s for the treatment of African trypanosomiasis (sleeping sickness)(https://www.cdc.gov/parasites/sleepingsickness/). Suramin generally is considered the drug of choice for first-stage Trypanosoma brucei rhodesiense (East African) infection, without involvement of the central nervous system. Pentamidine typically is used for first-stage T. b. gambiense (West African) infection.

More Information for Clinicians

Human African trypanosomiasis, WHO

Diagnostic assistance for African trypanosomiasis is available through DPDx.

How to Request

Contact the CDC Drug Service for more information.

Questions regarding treatment of African trypanosomiasis should be directed to CDC Parasitic Diseases Inquiries (404-718-4745; email parasites@cdc.gov) M-F 7:30am-4pm EST.

For emergencies outside of regular business hours, call the CDC Emergency Operations Center (770-488-7100) and ask for the person on call for Parasitic Diseases.

Vaccinia Vaccine, “Smallpox Vaccine”

Smallpox vaccine is made of live vaccinia virus derived from plaque purification cloning of Dryvax® (calf lymph vaccine, New York City Board of Health Strain) and grown in African Green Monkey kidney (Vero) cells and tested to be free of adventitious agents. It contains approximately 2.5 – 12.5 x 105 plaque-forming units per dose.

Smallpox was declared globally eradicated in 1980. In 1982, Wyeth Laboratories, the only active manufacturer of licensed vaccinia vaccine in the United States, discontinued production; and, in 1983, distribution to the civilian population was discontinued. Since January 1982, smallpox vaccination has not been required for international travelers, and International Certificates of Vaccination no longer include smallpox vaccination. ACAM2000® is a new-generation smallpox vaccine that was licensed in 2010 for use as a medical countermeasure held by the Strategic National Stockpile.

CDC recommends vaccinia vaccine for laboratory workers who directly handle a) cultures or b) animals contaminated or infected with nonhighly attenuated vaccinia virus, recombinant vaccinia viruses derived from nonhighly attenuated vaccinia strains, or other orthopoxviruses that infect humans (e.g., monkeypox, cowpox, vaccinia, and variola). Other health-care workers (e.g., physicians and nurses) whose contact with nonhighly attenuated vaccinia viruses is limited to contaminated materials (e.g., dressings) and who adhere to appropriate infection control measures are at lower risk for inadvertent infection than laboratory workers. However, because a theoretical risk for infection exists, vaccination can be offered to this group. Read more[PDF – 930KB](https://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/pdf/rr/rr5010.pdf).

More Information for Clinicians

Full Prescribing Information for ACAM2000®[PDF – 11 pages]

ACAM2000® Medication Guide[PDF – 6 pages]

CDC’s Vaccine-Related Topics: Smallpox Vaccine

How to Request

Smallpox vaccine must be administered by or under the supervision of the physician who registers with CDC.

Ancillary supplies, such as bifurcated needles (for administration) and 1 mL tuberculin syringes with 25 gauge x 5/8″ needles (for reconstitution), are supplied with the vaccine.

Contact the CDC Drug Service for more information.

Requests for unapproved uses cannot be granted.

Products No Longer Supplied by Drug Service*

Botulinum Toxoid

Pentavalent (ABCDE) botulinum toxoid is a combination of aluminum phosphate-adsorbed toxoid derived from formalin-inactivated types A, B, C, D, and E botulinum toxins, with formaldehyde and thimerosal used as preservatives. Botulinum toxoid was distributed by CDC under an IND protocol for at-risk persons who were actively working or expected to be working with cultures of Clostridium botulinum or the toxins; in 2011, CDC discontinued its program to supply this vaccine. Read more(https://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/preview/mmwrhtml/mm6042a3.htm).

Botulinum Antitoxin Types AB & E

In March 2010, CDC announced the availability of a new heptavalent botulinum antitoxin (HBAT, Cangene Corporation). HBAT replaced the licensed bivalent botulinum antitoxin AB and an investigational monovalent botulinum antitoxin E (BAT-AB and BAT-E, Sanofi Pasteur), becoming the only botulinum antitoxin available in the United States for naturally occurring non-infant botulism. Read more(https://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/preview/mmwrhtml/mm5910a4.htm).

Vaccinia Immune Globulin (VIG)

Vaccinia immune globulin (VIG) is released from the CDC Strategic National Stockpile, if indicated, for the treatment of complications associated with vaccinia vaccination. Clinicians wishing to obtain VIG should contact the Emergency Operations Center (EOC) at 770-488-7100. They will be connected with CDC medical staff who can assist them in the diagnosis and management of patients with suspected complications of vaccinia vaccination.

*this list is not all-inclusive

Use of trade names is for identification only and does not imply endorsement by the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services.

WHO: New vector control response seen as game-changer

Friday, June 2nd, 2017The call came from the WHO Director-General in May 2016 for a renewed attack on the global spread of vector-borne diseases.

“What we are seeing now looks more and more like a dramatic resurgence of the threat from emerging and re-emerging infectious diseases,” Dr Margaret Chan told Member States at the Sixty-ninth World Health Assembly. “The world is not prepared to cope.”

Dr Chan noted that the spread of Zika virus disease, the resurgence of dengue, and the emerging threat from chikungunya were the result of weak mosquito control policies from the 1970s. It was during that decade that funding and efforts for vector control were greatly reduced.

‘Vector control has not been a priority’

Dr Ana Carolina Silva Santelli has witnessed this first-hand. As former head of the programme for malaria, dengue, Zika and chikungunya with Brazil’s Ministry of Health, she saw vector-control efforts wane over her 13 years there. Equipment such as spraying machines, supplies such as insecticides and personnel such as entomologists were not replaced as needed. “Vector control has not been a priority,” she said.

Today more than 80% of the world’s population is at risk of vector-borne disease, with half at risk of two or more diseases. Mosquitoes can transmit, among other diseases, malaria, lymphatic filariasis, Japanese encephalitis and West Nile; flies can transmit onchocerciasis, leishmaniasis and human African trypanosomiasis (sleeping sickness); and bugs or ticks can transmit Chagas disease, Lyme disease and encephalitis.

Together, the major vector-borne diseases kill more than 700 000 people each year, with populations in poverty-stricken tropical and subtropical areas at highest risk. Other vector-borne diseases, such as tick-borne encephalitis, are of increasing concern in temperate regions.

Rapid unplanned urbanization, massive increases in international travel and trade, altered agricultural practices and other environmental changes are fuelling the spread of vectors worldwide, putting more and more people at risk. Malnourished people and those with weakened immunity are especially susceptible.

A new approach

Over the past year, WHO has spearheaded a new strategic approach to reprioritize vector control. The Global Malaria Programme and the Department of Control of Neglected Tropical Diseases – along with the Special Programme for Research and Training in Tropical Diseases, have led a broad consultation tapping into the experience of ministries of health and technical experts. The process was steered by a group of eminent scientists and public health experts led by Dr Santelli and Professor Thomas Scott from the Department of Entomology and Nematology at the University of California, Davis and resulted in the Global Vector Control Response (GVCR) 2017–2030.

At its Seventieth session, the World Health Assembly unanimously welcomed the proposed response.

The GVCR outlines key areas of activity that will radically change the control of vector-borne diseases:

- Aligning action across sectors, since vector control is more than just spraying insecticides or delivering nets. That might mean ministries of health working with city planners to eradicate breeding sites used by mosquitoes;

- Engaging and mobilizing communities to protect themselves and build resilience against future disease outbreaks;

- Enhancing surveillance to trigger early responses to increases in disease or vector populations, and to identify when and why interventions are not working as expected; and

- Scaling-up vector-control tools and using them in combination to maximize impact on disease while minimizing impact on the environment.

Specifically, the new integrated approach calls for national programmes to be realigned so that public health workers can focus on the complete spectrum of relevant vectors and thereby control all of the diseases they cause.

Recognizing that efforts must be adapted to local needs and sustained, the success of the response will depend on the ability of countries to strengthen their vector-control programmes with financial resources and staff.

A call to pursue novel interventions aggressively

The GVCR also calls for the aggressive pursuit of promising novel interventions such as devising new insecticides; creating spatial repellents and odour-baited traps; improving house screening; pursuing development of a common bacterium that stops viruses from replicating inside mosquitoes; and modifying the genes of male mosquitoes so that their offspring die early.

Economic development also brings solutions. “If people lived in houses that had solid floors and windows with screens or air conditioning, they wouldn’t need a bednet,” said Professor Scott. “So, by improving people’s standard of living, we would significantly reduce these diseases.”

The call for a more coherent and holistic approach to vector control does not diminish the considerable advances made against individual vector-borne diseases.

Malaria is a prime example. Over the past 15 years, its incidence in sub-Saharan Africa has been cut by 45% – primarily due to the massive use of insecticide-treated bed nets and spraying of residual insecticides inside houses.

But that success has had a down side.

“We’ve been so successful, in some ways, with our control that we reduced the number of public health entomologists – the people who can do this stuff well,” said Professor Steve Lindsay, a public health entomologist at Durham University in Britain. “We’re a disappearing breed.”

The GVCR calls for countries to invest in a vector-control workforce trained in public health entomology and empowered in health care responses.

“We now need more nuanced control – not one-size-fits-all, but to tailor control to local conditions,” Professor Lindsay said. This is needed to tackle new and emerging diseases, but also to push towards elimination of others such as malaria, he said.

Dr Lindsay noted that, under the new strategic approach, individual diseases such as Zika, dengue and chikungunya will no longer be considered as separate threats. “What this represents is not three different diseases, but one mosquito – Aedes aegypti,” said Professor Lindsay.

GVCR dovetails with Sustainable Development Goals

The GVCR will also help countries achieve at least 6 of the 17 Sustainable Development Goals. Of direct relevance are goal 3 on good health and well-being, goal 6 on clean water and sanitation, and goal 11 on sustainable cities and communities.

The GVCR goals are ambitious – to reduce mortality from vector-borne diseases by at least 75% and incidence by at least 60% by 2030 – and to prevent epidemics in all countries.

The annual price tag is US$ 330 million globally, or about 5 cents per person – for workforce, coordination and surveillance costs. This is a modest additional investment in relation to insecticide-treated nets, indoor sprays and community-based activities, which usually exceed US$ 1 per person protected per year.

It also represents less than 10% of what is currently spent each year on strategies to control vectors that spread malaria, dengue and Chagas disease alone. Ultimately, the shift in focus to integrated and locally adapted vector control will save money.

‘A call for action’

Dr Santelli expressed optimism that the GVCR will help ministries of health around the world gain support from their governments for a renewed focus on vector control.

“Most of all, this document is a call for action,” said Dr Santelli, who now serves as deputy director for epidemiology in the Brasilia office of the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

It will not be easy, she predicts. The work to integrate vector-control efforts across different diseases will require more equipment, more people and more money as well as a change in mentality. “The risk of inaction is greater,” said Dr Santelli, “given the growing number of emerging disease threats.” The potential impact of the GVCR is immense: to put in place new strategies that will reduce overall burden and, in some places, even eliminate these diseases once and for all.

Chagas Disease: Approximately 300,000 people are living with this disease in the United States.

Sunday, April 23rd, 2017

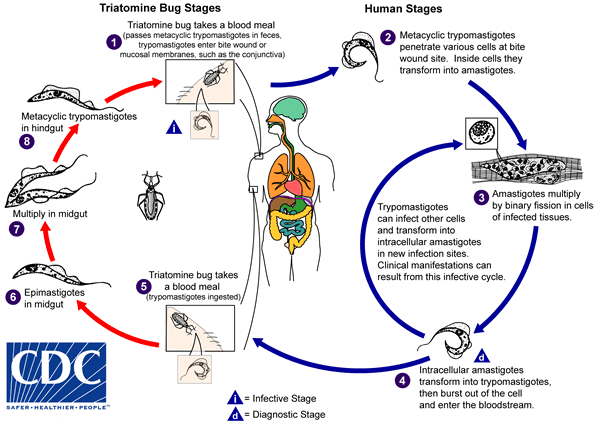

An infected triatomine insect vector (or “kissing” bug) takes a blood meal and releases trypomastigotes in its feces near the site of the bite wound. Trypomastigotes enter the host through the wound or through intact mucosal membranes, such as the conjunctiva  . Common triatomine vector species for trypanosomiasis belong to the genera Triatoma, Rhodnius, and Panstrongylus. Inside the host, the trypomastigotes invade cells near the site of inoculation, where they differentiate into intracellular amastigotes

. Common triatomine vector species for trypanosomiasis belong to the genera Triatoma, Rhodnius, and Panstrongylus. Inside the host, the trypomastigotes invade cells near the site of inoculation, where they differentiate into intracellular amastigotes  . The amastigotes multiply by binary fission

. The amastigotes multiply by binary fission  and differentiate into trypomastigotes, and then are released into the circulation as bloodstream trypomastigotes

and differentiate into trypomastigotes, and then are released into the circulation as bloodstream trypomastigotes  . Trypomastigotes infect cells from a variety of tissues and transform into intracellular amastigotes in new infection sites. Clinical manifestations can result from this infective cycle. The bloodstream trypomastigotes do not replicate (different from the African trypanosomes). Replication resumes only when the parasites enter another cell or are ingested by another vector. The “kissing” bug becomes infected by feeding on human or animal blood that contains circulating parasites

. Trypomastigotes infect cells from a variety of tissues and transform into intracellular amastigotes in new infection sites. Clinical manifestations can result from this infective cycle. The bloodstream trypomastigotes do not replicate (different from the African trypanosomes). Replication resumes only when the parasites enter another cell or are ingested by another vector. The “kissing” bug becomes infected by feeding on human or animal blood that contains circulating parasites  . The ingested trypomastigotes transform into epimastigotes in the vector’s midgut

. The ingested trypomastigotes transform into epimastigotes in the vector’s midgut  . The parasites multiply and differentiate in the midgut

. The parasites multiply and differentiate in the midgut  and differentiate into infective metacyclic trypomastigotes in the hindgut

and differentiate into infective metacyclic trypomastigotes in the hindgut  .

.

Trypanosoma cruzi can also be transmitted through blood transfusions, organ transplantation, transplacentally, and in laboratory accidents.

Chagas disease is caused by the parasite Trypanosoma cruzi, which is transmitted to animals and people by insect vectors that are found only in the Americas (mainly, in rural areas of Latin America where poverty is widespread). Chagas disease (T. cruzi infection) is also referred to as American trypanosomiasis.

It is estimated that as many as 8 million people in Mexico, Central America, and South America have Chagas disease, most of whom do not know they are infected. If untreated, infection is lifelong and can be life threatening.

The impact of Chagas disease is not limited to the rural areas in Latin America in which vectorborne transmission occurs. Large-scale population movements from rural to urban areas of Latin America and to other regions of the world have increased the geographic distribution and changed the epidemiology of Chagas disease. In the United States and in other regions where Chagas disease is now found but is not endemic, control strategies should focus on preventing transmission from blood transfusion, organ transplantation, and mother-to-baby (congenital transmission).

How do people get Chagas disease?

People can become infected in various ways. In Chagas disease-endemic areas, the main way is through vectorborne transmission. The insect vectors are called triatomine bugs. These blood-sucking bugs get infected by biting an infected animal or person. Once infected, the bugs pass T. cruzi parasites in their feces. The bugs are found in houses made from materials such as mud, adobe, straw, and palm thatch. During the day, the bugs hide in crevices in the walls and roofs. During the night, when the inhabitants are sleeping, the bugs emerge. Because they tend to feed on people’s faces, triatomine bugs are also known as “kissing bugs. ” After they bite and ingest blood, they defecate on the person. The person can become infected if T. cruzi parasites in the bug feces enter the body through mucous membranes or breaks in the skin. The unsuspecting, sleeping person may accidentally scratch or rub the feces into the bite wound, eyes, or mouth.

People also can become infected through:

- congenital transmission (from a pregnant woman to her baby);

- blood transfusion;

- organ transplantation;

- consumption of uncooked food contaminated with feces from infected bugs; and

- accidental laboratory exposure.

It is generally considered safe to breastfeed even if the mother has Chagas disease. However, if the mother has cracked nipples or blood in the breast milk, she should pump and discard the milk until the nipples heal and the bleeding resolves.

Chagas disease is not transmitted from person-to-person like a cold or the flu or through casual contact with infected people or animals.

If I have Chagas disease, should my family members be tested for the infection?

Possibly. They should be tested if they:

- could have become infected the same way that you did, for example, by vectorborne transmission in Latin America;

- received blood or organs that you donated after you already were infected;

- are your children and were born after you were infected; or if

- there are other reasons to think that they might have Chagas disease.

In what parts of the world is Chagas disease found?

People who have Chagas disease can be found anywhere in the world. However, vectorborne transmission is confined to the Americas, principally rural areas in parts of Mexico, Central America, and South America. In some regions of Latin America, vector-control programs have succeeded in stopping this type of disease spread. Vectorborne transmission does not occur in the Caribbean (for example, in Puerto Rico or Cuba). Rare vectorborne cases of Chagas disease have been noted in the southern United States.

What are the signs and symptoms of Chagas disease?

Much of the clinical information about Chagas disease comes from experience with people who became infected as children through vectorborne transmission. The severity and course of infection might be different in people infected at other times of life, in other ways, or with different strains of the T. cruzi parasite.

There are two phases of Chagas disease: the acute phase and the chronic phase. Both phases can be symptom free or life threatening.

The acute phase lasts for the first few weeks or months of infection. It usually occurs unnoticed because it is symptom free or exhibits only mild symptoms and signs that are not unique to Chagas disease. The symptoms noted by the patient can include fever, fatigue, body aches, headache, rash, loss of appetite, diarrhea, and vomiting. The signs on physical examination can include mild enlargement of the liver or spleen, swollen glands, and local swelling (a chagoma) where the parasite entered the body. The most recognized marker of acute Chagas disease is called Romaña’s sign, which includes swelling of the eyelids on the side of the face near the bite wound or where the bug feces were deposited or accidentally rubbed into the eye. Even if symptoms develop during the acute phase, they usually fade away on their own, within a few weeks or months. Although the symptoms resolve, if untreated the infection persists. Rarely, young children (<5%) die from severe inflammation/infection of the heart muscle (myocarditis) or brain (meningoencephalitis). The acute phase also can be severe in people with weakened immune systems.

During the chronic phase, the infection may remain silent for decades or even for life. However, some people develop:

- cardiac complications, which can include an enlarged heart (cardiomyopathy), heart failure, altered heart rate or rhythm, and cardiac arrest (sudden death); and/or

- intestinal complications, which can include an enlarged esophagus (megaesophagus) or colon (megacolon) and can lead to difficulties with eating or with passing stool.

The average life-time risk of developing one or more of these complications is about 30%.

What should I do if I think I have Chagas disease?

You should discuss your concerns with your health care provider, who will examine you and ask you questions (for example, about your health and where you have lived). Chagas disease is diagnosed by blood tests. If you are found to have Chagas disease, you should have a heart tracing test (electrocardiogram), even if you feel fine. You might be referred to a specialist for more tests and for treatment.

What if I’ve been diagnosed with Chagas disease but have a normal EKG?

If you have been diagnosed with Chagas disease, your doctor may perform an electrocardiogram (EKG or ECG) to check for any problems with the electrical activity of your heart. Even if this test is normal, you still may need to be given antiparasitic medication used to treat Chagas disease. Your physician may wish to review CDC’s recommendations for evaluation and treatment for more information.

How is Chagas disease treated?

There are two approaches to therapy, both of which can be life saving:

- antiparasitic treatment, to kill the parasite; and

- symptomatic treatment, to manage the symptoms and signs of infection.

Antiparasitic treatment is most effective early in the course of infection but is not limited to cases in the acute phase. In the United States, this type of treatment is available through CDC. Your health care provider can talk with CDC staff about whether and how you should be treated. Most people do not need to be hospitalized during treatment.

Symptomatic treatment may help people who have cardiac or intestinal problems from Chagas disease. For example, pacemakers and medications for irregular heartbeats may be life saving for some patients with chronic cardiac disease.

I plan to travel to a rural area of Latin America that might have Chagas disease. How can I prevent infection?

No drugs or vaccines for preventing infection are currently available. Travelers who sleep indoors, in well-constructed facilities (for example, air-conditioned or screened hotel rooms), are at low risk for exposure to infected triatomine bugs, which infest poor-quality dwellings and are most active at night. Preventive measures include spraying infested dwellings with residual-action insecticides, using bed nets treated with long-lasting insecticides, wearing protective clothing, and applying insect repellent to exposed skin. In addition, travelers should be aware of other possible routes of transmission, including bloodborne and foodborne.

Chagas disease fears along the Texas-Mexico border

Monday, November 14th, 2016Garcia MN, O’Day S, Fisher-Hoch S, Gorchakov R, Patino R, Feria Arroyo TP, et al. (2016) One Health Interactions of Chagas Disease Vectors, Canid Hosts, and Human Residents along the Texas-Mexico Border. PLoS Negl Trop Dis 10(11): e0005074. doi:10.1371/journal.pntd.0005074

Background

Chagas disease (Trypanosoma cruzi infection) is the leading cause of non-ischemic dilated cardiomyopathy in Latin America. Texas, particularly the southern region, has compounding factors that could contribute to T. cruzi transmission; however, epidemiologic studies are lacking. The aim of this study was to ascertain the prevalence of T. cruzi in three different mammalian species (coyotes, stray domestic dogs, and humans) and vectors (Triatoma species) to understand the burden of Chagas disease among sylvatic, peridomestic, and domestic cycles.

Methodology/Principal Findings

To determine prevalence of infection, we tested sera from coyotes, stray domestic dogs housed in public shelters, and residents participating in related research studies and found 8%, 3.8%, and 0.36% positive for T. cruzi, respectively. PCR was used to determine the prevalence of T. cruzi DNA in vectors collected in peridomestic locations in the region, with 56.5% testing positive for the parasite, further confirming risk of transmission in the region.

Conclusions/Significance

Our findings contribute to the growing body of evidence for autochthonous Chagas disease transmission in south Texas. Considering this region has a population of 1.3 million, and up to 30% of T. cruzi infected individuals developing severe cardiac disease, it is imperative that we identify high risk groups for surveillance and treatment purposes.