Archive for March, 2016

Alaska: Pavlof Volcano erupted about 4 p.m. Sunday, spitting out an ash cloud that rose to 37,000 feet.

Tuesday, March 29th, 2016The U.S.-led coalition said the chemicals ISIS has so far used include chlorine and a low-grade sulfur mustard.

Tuesday, March 29th, 2016March 28, 1979: The worst accident in the history of the U.S. nuclear power industry begins when a pressure valve in the Unit-2 reactor at Three Mile Island fails to close.

Monday, March 28th, 2016** The core eventually heated to over 4,000 degrees, just 1,000 degrees short of meltdown.

Pakistan: A bombing (suicide?) on Easter Sunday killed 65 people (mostly women and children) in a park in Lahore that was crowded with Christians

Monday, March 28th, 2016** over 300 wounded

Characteristics of 115 residents of U.S. states and the District of Columbia with laboratory evidence of Zika virus disease — January 1, 2015–February 26, 2016

Monday, March 28th, 2016Travel-Associated Zika Virus Disease Cases Among U.S. Residents — United States, January 2015–February 2016

Weekly / March 25, 2016 / 65(11);286–289

Summary

What is already known about this topic?Zika virus is an emerging mosquito-borne flavivirus. Recent outbreaks of Zika virus disease in the Pacific Islands and the Region of the Americas have identified new modes of transmission and clinical manifestations, including adverse pregnancy outcomes.

What is added by this report?During January 1, 2015–February 26, 2016, a total of 116 residents of U.S. states and the District of Columbia had laboratory evidence of recent Zika virus infection based on testing performed at CDC, including one congenital infection and 115 persons who reported recent travel to areas with active Zika virus transmission (n = 110) or sexual contact with such a traveler (n = 5).

What are the implications for public health practice?Health care providers should educate patients about the risks for Zika virus disease and measures to prevent Zika virus infection and other mosquito-borne infections. Zika virus disease should be considered in patients with acute onset of fever, rash, arthralgia, or conjunctivitis who traveled to areas with ongoing transmission or had unprotected sex with someone who traveled to those areas and developed compatible symptoms within 2 weeks of returning.

Zika virus is an emerging mosquito-borne flavivirus. Recent outbreaks of Zika virus disease in the Pacific Islands and the Region of the Americas have identified new modes of transmission and clinical manifestations, including adverse pregnancy outcomes. However, data on the epidemiology and clinical findings of laboratory-confirmed Zika virus disease remain limited. During January 1, 2015–February 26, 2016, a total of 116 residents of 33 U.S. states and the District of Columbia had laboratory evidence of recent Zika virus infection based on testing performed at CDC. Cases include one congenital infection and 115 persons who reported recent travel to areas with active Zika virus transmission (n = 110) or sexual contact with such a traveler (n = 5). All 115 patients had clinical illness, with the most common signs and symptoms being rash (98%; n = 113), fever (82%; 94), and arthralgia (66%; 76). Health care providers should educate patients, particularly pregnant women, about the risks for, and measures to prevent, infection with Zika virus and other mosquito-borne viruses. Zika virus disease should be considered in patients with acute onset of fever, rash, arthralgia, or conjunctivitis, who traveled to areas with ongoing Zika virus transmission (http://www.cdc.gov/zika/geo/index.html) or who had unprotected sex with a person who traveled to one of those areas and developed compatible symptoms within 2 weeks of returning.

Zika virus is primarily transmitted to humans by Aedes aegypti mosquitoes (1). Most infections are asymptomatic (2). When occurring, clinical illness is generally mild and characterized by acute onset of fever, maculopapular rash, arthralgia, or nonpurulent conjunctivitis. Symptoms usually last from several days to a week. Severe disease requiring hospitalization is uncommon, and deaths are rare.

In addition to mosquito-borne transmission, Zika virus infections have been reported through intrauterine transmission resulting in congenital infection, intrapartum transmission from a viremic mother to her newborn, sexual transmission, and laboratory exposure (3,4). Increasing evidence suggests that Zika virus infection during pregnancy can result in microcephaly, other congenital anomalies, and fetal losses (5). Guillain-Barré syndrome also has been associated with recent Zika virus disease (6). However, the frequency of these outcomes is not known. To characterize Zika virus disease among U.S. residents, CDC reviewed demographics, exposures, and reported symptoms of patients with laboratory-evidence of recent Zika virus infection in the United States.

Zika virus disease cases among residents of U.S. states with specimens tested at CDC’s Arboviral Diseases Branch during January 1, 2015–February 26, 2016 were identified. The cases included in this report had laboratory evidence of Zika virus infection based on the following findings in serum: 1) Zika virus RNA detected by reverse transcription-polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR); 2) anti-Zika virus immunoglobulin M (IgM) antibodies detected by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) with ≥4-fold higher neutralizing antibody titers against Zika virus compared with neutralizing antibody titers against dengue virus; or 3) anti-Zika virus IgM antibodies with <4-fold difference in neutralizing antibody titers between Zika and dengue viruses and a direct epidemiologic link to a person with laboratory evidence of recent Zika virus infection (i.e., vertical transmission from mother to baby or sexual contact). State and local health departments collected information on patient demographics, dates of travel, and clinical signs and symptoms.

During January 1, 2015–February 26, 2016, a total of 116 residents of 33 states and the District of Columbia with laboratory evidence of recent Zika virus infection were identified on the basis of testing at CDC. One case occurred in a full-term infant born with severe congenital microcephaly, whose mother had Zika virus disease in Brazil during the first trimester of pregnancy (5). Among the remaining 115 patients (including the infant’s mother), 24 (21%) had illness onset in 2015 and 91 (79%) in 2016. Seventy-five (65%) cases occurred in females (Table 1). The median age of patients was 38 years (range = 3–81 years); 11 (10%) cases occurred in children and adolescents aged <18 years. Of the 115 patients, 110 (96%) reported recent travel to areas of active Zika virus transmission and five (4%) did not travel but reported sexual contact with a traveler who had symptomatic illness. The most frequently reported countries with active Zika virus transmission visited by patients were Haiti (n = 27), El Salvador (16), Colombia (11), Honduras (11), and Guatemala (10).

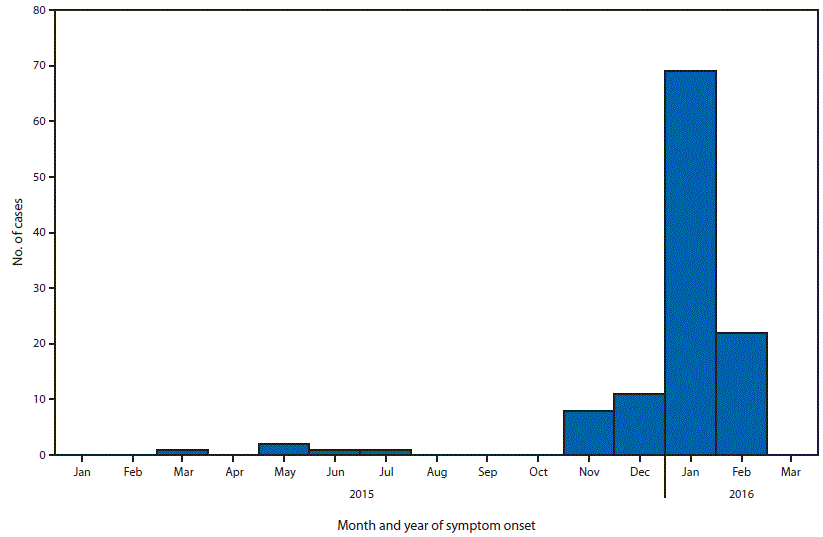

All 115 patients reported a clinical illness with onset during March 2015–February 2016 (Figure). The most commonly reported signs and symptoms were rash (98%), fever (82%), arthralgia (66%), headache (57%), myalgia (55%), and conjunctivitis (37%) (Table 2). Among all 115 patients, 110 (96%) reported two or more of the following symptoms: rash, fever, arthralgia, and conjunctivitis; 75 (65%) reported three or more of these signs or symptoms. Four (3%) patients were hospitalized; no deaths occurred. Among the 109 travelers who had known travel dates, patients reported becoming ill a median of 1 day after returning home (range = 37 days before return to 11 days after return).

Laboratory evidence of Zika virus infection included positive RT-PCR test results in 28 (24%) cases and positive serologic test results in 87 (76%) cases; two (2%) cases had serologic evidence of a recent unspecified flavivirus infection and were classified as Zika virus disease cases based on their epidemiologic link to a confirmed case (one vertical transmission and one sexual contact).

Discussion

Before 2015, Zika virus disease among U.S. travelers was uncommon. This likely was because of low levels of Zika virus transmission in travel destinations and limited disease recognition in the United States. Local mosquito-borne transmission of Zika virus has not been documented in U.S. states. With the recent outbreaks in the Americas, the number of Zika virus disease cases among travelers visiting or returning to the United States has increased and will likely continue to increase. These imported cases might result in local human-to-mosquito-to-human transmission of the virus in U.S. states that have the appropriate mosquito vectors.

This report increases the number of laboratory-confirmed sexually transmitted Zika virus disease cases reported in the United States; two cases included here were previously reported as probable cases and were confirmed through additional testing (4). Sexually transmitted cases will be increasingly recognized among contacts of returning travelers and there is risk for congenital, perinatal, or transfusion-associated transmission. CDC has issued guidelines to reduce the risk for travel-associated infections, especially among pregnant women and sexual contacts of travelers (4,7). Temporary deferral of blood donors with recent travel to Zika-affected areas also has been recommended to reduce the risk for transfusion-associated transmission (8).

The cases presented in this report have clinical findings similar to those of Zika virus disease cases previously reported from other countries. Most had fever and rash; however, rates of conjunctivitis are lower than those seen in previous outbreaks (2). The majority (95%) of cases occurred in travelers to areas with ongoing mosquito-borne Zika virus transmission.

This evaluation was limited to cases with testing performed at CDC through February 26, 2016. Zika virus RT-PCR and anti-Zika IgM antibody testing is now available at an increasing number of state, territorial, and local health departments, and additional cases have been diagnosed and reported from state and territorial health departments beyond those included in this report (http://www.cdc.gov/zika/geo/united-states.html). On February 26, 2016, the Council of State and Territorial Epidemiologists (CSTE) approved interim case definitions for Zika virus disease and Zika virus congenital infection and added them to the list of nationally notifiable conditions (9). Subsequent reports of Zika virus disease cases will include cases reported to ArboNET, the national arboviral surveillance system, using the interim CSTE case definitions.

Health care providers should educate patients about the risks for Zika virus disease and measures to prevent Zika virus infection and other mosquito-borne infections. Zika virus disease should be considered in patients with acute onset of fever, rash, arthralgia, or conjunctivitis who traveled to areas with ongoing transmission or had unprotected sex with someone who traveled to those areas and developed compatible symptoms within 2 weeks of returning. Until more is known about the effects of Zika virus infection on the developing fetus, pregnant women should postpone travel to areas where Zika virus transmission is ongoing. Pregnant women who do travel to one of these areas should talk to their health care provider before traveling and strictly follow steps to avoid mosquito bites (http://www.cdc.gov/features/stopmosquitoes/) during travel. Pregnant women who develop a clinically compatible illness during or within 2 weeks of returning from an area with Zika virus transmission should be tested for Zika virus infection; testing may also be offered to asymptomatic pregnant women 2–12 weeks after travel to an area with active Zika transmission (7). Fetuses and infants of women infected with Zika virus during pregnancy should be evaluated for possible congenital infection (10). CDC has established a registry to collect information on Zika virus infection during pregnancy and congenital infection.

Health care providers are encouraged to report suspected Zika virus disease cases to their state or local health departments to facilitate diagnosis and mitigate the risk for local transmission in areas where Aedes aegypti or Aedes albopictus mosquitoes are currently active. State health departments should report laboratory-confirmed cases of Zika virus disease to CDC (8).

References

- Hayes EB. Zika virus outside Africa. Emerg Infect Dis 2009;15:1347–50 . CrossRef PubMed

- Duffy MR, Chen TH, Hancock WT, et al. Zika virus outbreak on Yap Island, Federated States of Micronesia. N Engl J Med 2009;360:2536–43 . CrossRef PubMed

- European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control. Zika virus disease epidemic: potential association with microcephaly and Guillain-Barré syndrome. Stockholm, Sweden: European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control; 2016. http://ecdc.europa.eu/en/publications/Publications/zika-virus-rapid-risk-assessment-9-march-2016.pdf

- Hills SL, Russell K, Hennessey M, et al. Transmission of Zika virus through sexual contact with travelers to areas of ongoing transmission—continental United States, 2016. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2016;65:215–6 . CrossRef PubMed

- Meaney-Delman D, Hills SL, Williams C, et al. Zika virus infection among US pregnant travelers—August 2015–February 2016. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2016;65:211–4 . CrossRef PubMed

- Cao-Lormeau VM, Blake A, Mons S, et al. Guillain-Barré syndrome outbreak associated with Zika virus infection in French Polynesia: a case-control study. Lancet. Epub, March 2, 2016. CrossRef PubMed

- Oduyebo T, Petersen EE, Rasmussen SA, et al. Update: interim guidelines for health care providers caring for pregnant women and women of reproductive age with possible Zika virus exposure—United States, 2016. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2016;65:122–7 . CrossRef PubMed

- US Food and Drug Administration. Recommendations for donor screening, deferral, and product management to reduce the risk of transfusion-transmission of Zika virus. Washington, DC: US Food and Drug Administration; 2016. http://www.fda.gov/downloads/BiologicsBloodVaccines/GuidanceComplianceRegulatoryInformation/Guidances/Blood/UCM486360.pdf

- Council of State and Territorial Epidemiologists. Zika virus disease and congenital Zika virus infection interim case definition and addition to the Nationally Notifiable Disease List. Atlanta, GA: Council of State and Territorial Epidemiologists; 2016. https://www.cste2.org/docs/Zika_Virus_Disease_and_Congenital_Zika_Virus_Infection_Interim.pdf

- Fleming-Dutra KE, Nelson JM, Fischer M, et al. Update: interim guidelines for health care providers caring for infants and children with possible Zika virus infection—United States, February 2016. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2016;65:182–7 . CrossRef PubMed

TABLE 1. Characteristics of 115 residents of U.S. states and the District of Columbia with laboratory evidence of Zika virus disease — January 1, 2015–February 26, 2016*,†

TABLE 1. Characteristics of 115 residents of U.S. states and the District of Columbia with laboratory evidence of Zika virus disease — January 1, 2015–February 26, 2016*,†

| Characteristic | No. (%) |

|---|---|

| Female | 75 (65) |

| Age group (yrs) | |

| <10 | 4 (3) |

| 10–19 | 10 (9) |

| 20–29 | 23 (20) |

| 30–39 | 22 (19) |

| 40–49 | 19 (17) |

| 50–59 | 23 (20) |

| 60–69 | 13 (11) |

| ≥70 | 1 (1) |

| Region visited | |

| Central America | 42 (37) |

| Caribbean | 38 (33) |

| South America | 21 (18) |

| Southeast Asia and Pacific Islands | 7 (6) |

| North America (Mexico) | 2 (2) |

| No travel§ | 5 (4) |

| Hospitalized | 4 (3) |

| Died | 0 (0) |

* Testing performed at CDC’s Arboviral Diseases Branch laboratory.

† Excludes one infant born with severe congenital microcephaly after maternal infection in Brazil during the first trimester of pregnancy.

§ Sexual contacts of travelers.

FIGURE. Month of illness onset for 115 patients with laboratory evidence of Zika virus infection among residents of U.S. states and the District of Columbia — January 1, 2015–February 26, 2016*

FIGURE. Month of illness onset for 115 patients with laboratory evidence of Zika virus infection among residents of U.S. states and the District of Columbia — January 1, 2015–February 26, 2016*

*Testing performed at CDC’s Arboviral Diseases Branch laboratory.

TABLE 2. Clinical signs and symptoms reported by 115 residents of U.S. states and the District of Columbia with laboratory evidence of Zika virus disease — January 1, 2015–February 26, 2016*

TABLE 2. Clinical signs and symptoms reported by 115 residents of U.S. states and the District of Columbia with laboratory evidence of Zika virus disease — January 1, 2015–February 26, 2016*

| Yes† | No | Unknown | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sign/symptom | No. (%) | No. (%) | No. (%) |

| Rash | 113 (98) | 1 (1) | 1 (1) |

| Fever | 94 (82) | 20 (17) | 1 (1) |

| Arthralgia | 76 (66) | 33 (29) | 6 (5) |

| Headache | 65 (57) | 37 (32) | 13 (11) |

| Myalgia | 63 (55) | 38 (33) | 14 (12) |

| Conjunctivitis | 43 (37) | 53 (46) | 19 (17) |

| Diarrhea | 22 (19) | 63 (55) | 30 (26) |

| Vomiting | 6 (5) | 79 (69) | 30 (26) |

* Testing performed at CDC’s Arboviral Diseases Branch laboratory.

† Some patients had more than one sign and/or symptom.

Suggested citation for this article: Armstrong P, Hennessey M, Adams M, et al. Travel-Associated Zika Virus Disease Cases Among U.S. Residents — United States, January 2015–February 2016. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2016;65:286–289. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.15585/mmwr.mm6511e1.

Zika Virus: Puerto Rico & Contraceptives

Monday, March 28th, 2016Estimating Contraceptive Needs and Increasing Access to Contraception in Response to the Zika Virus Disease Outbreak — Puerto Rico, 2016

Naomi K. Tepper, MD; Howard I. Goldberg, PhD; Manuel I. Vargas Bernal, MD; et al.

MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2016;65(Early Release)

As of March 16, 2016, the highest number of Zika virus disease cases in the United States and U.S. territories were reported from Puerto Rico. Increasing evidence links Zika virus infection during pregnancy to adverse pregnancy and birth outcomes. High rates of unintended and adolescent pregnancies in Puerto Rico suggest access to contraception might need to be improved in the context of this outbreak

Men who have traveled to or reside in areas with active Zika virus transmission and their female or male sex partners: What to do?

Monday, March 28th, 2016Update: Interim Guidance for Prevention of Sexual Transmission of Zika Virus — United States, 2016

Alexandra M. Oster, MD; Kate Russell, MD; Jo Ellen Stryker, PhD; et al.

MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2016;65(Early Release)

CDC issued interim guidance for the prevention of sexual transmission of Zika virus on February 5, 2016. The following recommendations apply to men who have traveled to or reside in areas with active Zika virus transmission and their female or male sex partners. These recommendations replace the previously issued recommendations and are updated to include time intervals after travel to areas with active Zika virus transmission or after Zika virus infection for taking precautions to reduce the risk for sexual transmission

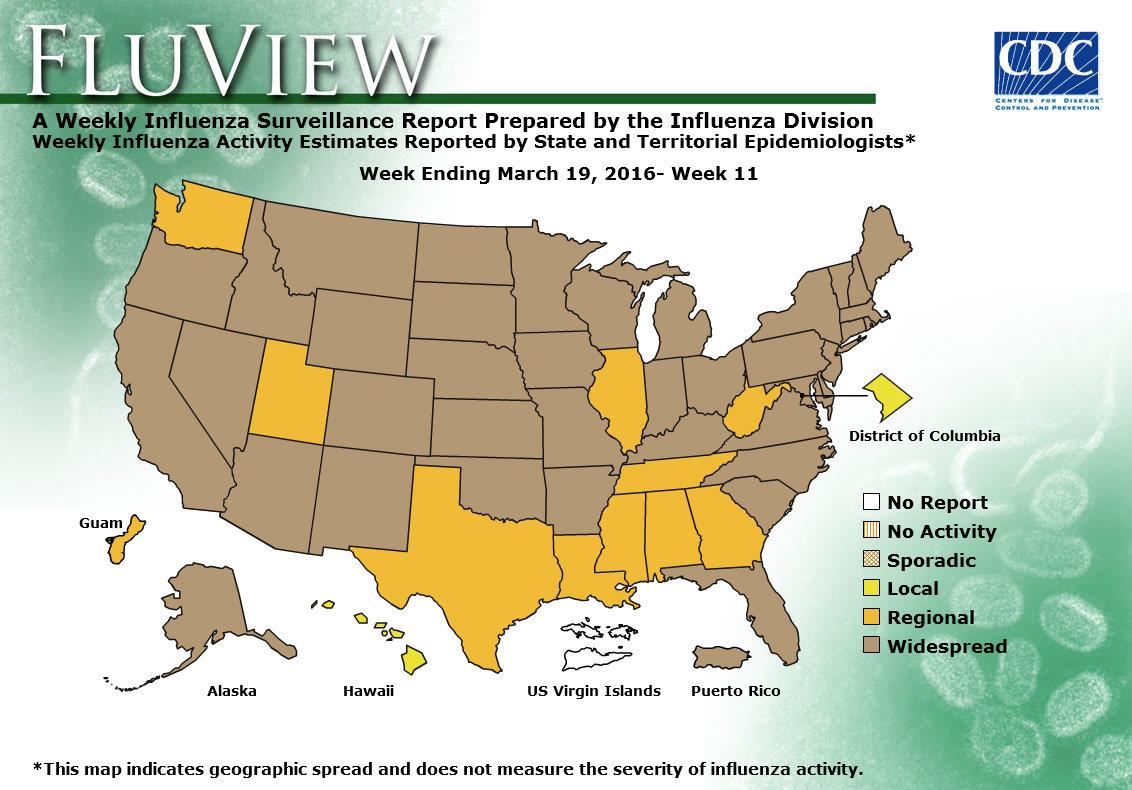

During week 11 (March 13-19, 2016), influenza activity decreased slightly, but remained elevated in the United States.

Sunday, March 27th, 2016

Synopsis:

During week 11 (March 13-19, 2016), influenza activity decreased slightly, but remained elevated in the United States.

- Viral Surveillance: The most frequently identified influenza virus type reported by public health laboratories during week 11 was influenza A, with influenza A (H1N1)pdm09 viruses predominating. The percentage of respiratory specimens testing positive for influenza in clinical laboratories decreased.

- Novel Influenza A Virus: One human infection with a novel influenza A virus was reported.

- Pneumonia and Influenza Mortality: The proportion of deaths attributed to pneumonia and influenza (P&I) was below the system-specific epidemic threshold in the NCHS Mortality Surveillance System and above the system-specific epidemic threshold in the 122 Cities Mortality Reporting System.

- Influenza-associated Pediatric Deaths: Two influenza-associated pediatric deaths were reported.

- Influenza-associated Hospitalizations: A cumulative rate for the season of 18.2 laboratory-confirmed influenza-associated hospitalizations per 100,000 population was reported.

- Outpatient Illness Surveillance: The proportion of outpatient visits for influenza-like illness (ILI) was 3.2%, which is above the national baseline of 2.1%. All 10 regions reported ILI at or above region-specific baseline levels. Puerto Rico and seven states experienced high ILI activity; New York City and eight states experienced moderate ILI activity; 20 states experienced low ILI activity; 15 states experienced minimal ILI activity; and the District of Columbia had insufficient data.

- Geographic Spread of Influenza: The geographic spread of influenza in Puerto Rico and 39 states was reported as widespread; Guam and 10 states reported regional activity; the District of Columbia and one state reported local activity; and the U.S. Virgin Islands did not report.

<!–

–>

* More than 86.7 million children under the age of 7 have spent their entire lives in conflict zones, putting them at risk of living in a state of toxic stress, a condition that inhibits brain cell connections — with significant life-long consequences to their cognitive, social and physical development.

Sunday, March 27th, 2016

NEW YORK, 24 March 2016 – More than 86.7 million children under the age of 7 have spent their entire lives in conflict zones, putting their brain development at risk, UNICEF said today.

During the first 7 years of life a child’s brain has the potential to activate 1,000 brain cells every second. Each one of those cells, known as neurons, has the power to connect to another 10,000 neurons thousands of times per second. Brain connections serve as the building blocks of a child’s future, defining their health, emotional well-being and ability to learn.

Children living in conflict are often exposed to extreme trauma, putting them at risk of living in a state of toxic stress, a condition that inhibits brain cell connections — with significant life-long consequences to their cognitive, social and physical development.

“In addition to the immediate physical threats that children in crises face, they are also at risk of deep-rooted emotional scars,” UNICEF Chief of Early Child Development Pia Britto said.

UNICEF figures show that globally one in 11 children aged 6 or younger has spent the most critical period of brain development growing up in conflict.

“Conflict robs children of their safety, family and friends, play and routine. Yet these are all elements of childhood that give children the best possible chance of developing fully and learning effectively, enabling them to contribute to their economies and societies, and building strong and safe communities when they reach adulthood,” Britto said.

“That is why we need to invest more to provide children and caregivers with critical supplies and services including learning materials, psychosocial support, and safe, child-friendly spaces that can help restore a sense of childhood in the midst of conflict.”

A child is born with 253 million functioning neurons, but whether the brain reaches its full adult capacity of around one billion connectable neurons depends in large part on early childhood development. This includes breastfeeding and early nutrition, early stimulation by caregivers, early learning opportunities and a chance to grow and play in a safe and healthy environment.

As part of our response in humanitarian emergencies and protracted crises, UNICEF works to keep children in child-friendly environments, providing emergency kits with learning and play materials. The emergency kits have supported more than 800,000 children living in emergency contexts in the past year alone.

A teenager who surrendered before carrying out a suicide bombing attack in northern Cameroon has told authorities she was one of the 276 girls abducted from a Nigerian boarding school by Islamic extremists nearly two years ago.

Sunday, March 27th, 2016

** “The girl looked tired, malnourished and psychologically tortured and could not give us more details about her stay in the forest and how her other mates were treated.”