Archive for February, 2017

China: Increasing rate of MCR-1 carriage in humans

Monday, February 13th, 2017High rates of human faecal carriage of mcr-1-positive multi-drug resistant isolates emerge in China in association with successful plasmid families

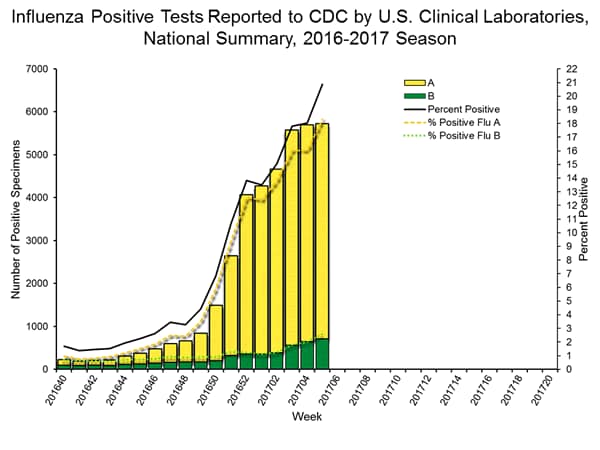

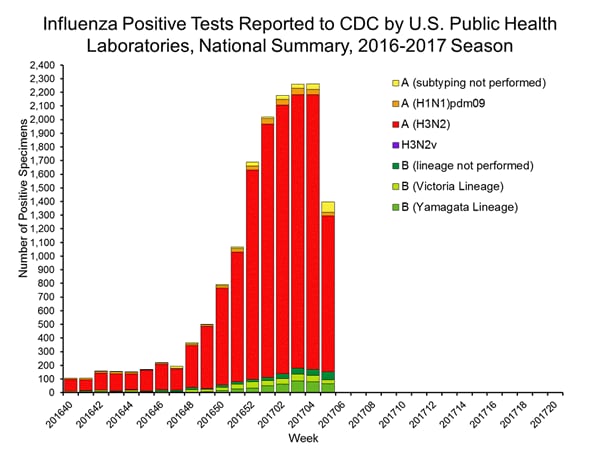

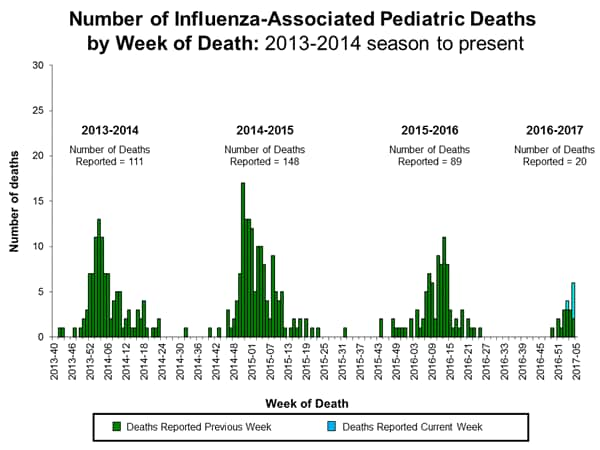

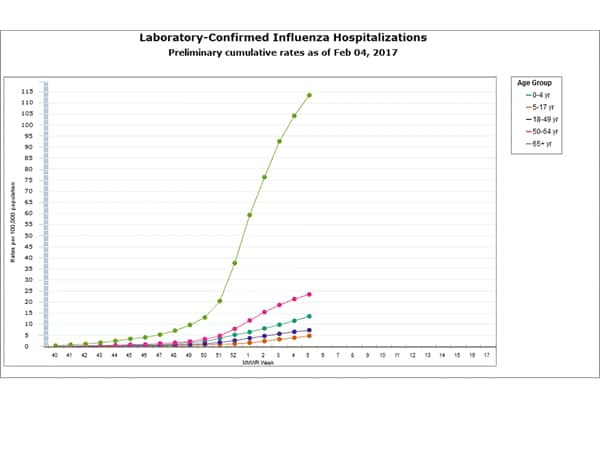

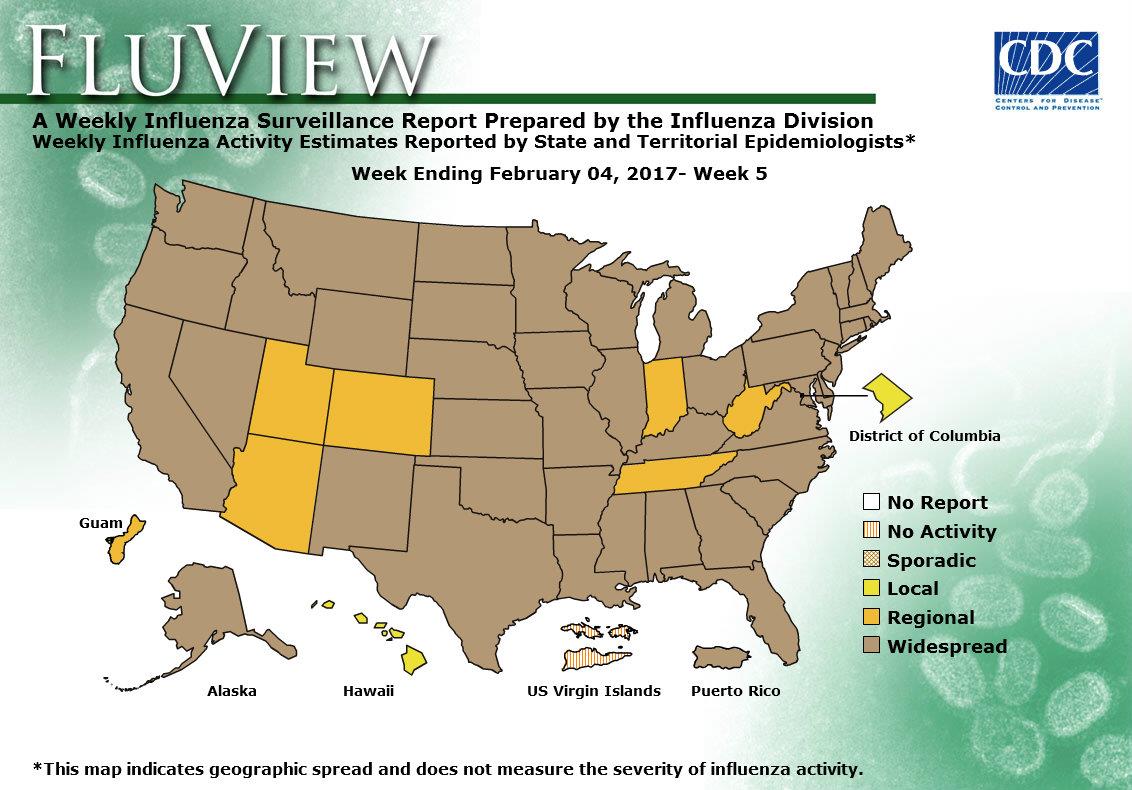

2016-2017 Influenza Season Week 5 ending February 4, 2017

Saturday, February 11th, 2017During week 5 (January 29-February 4, 2017), influenza activity increased in the United States.

- Viral Surveillance: The most frequently identified influenza virus subtype reported by public health laboratories during week 5 was influenza A (H3). The percentage of respiratory specimens testing positive for influenza in clinical laboratories increased.

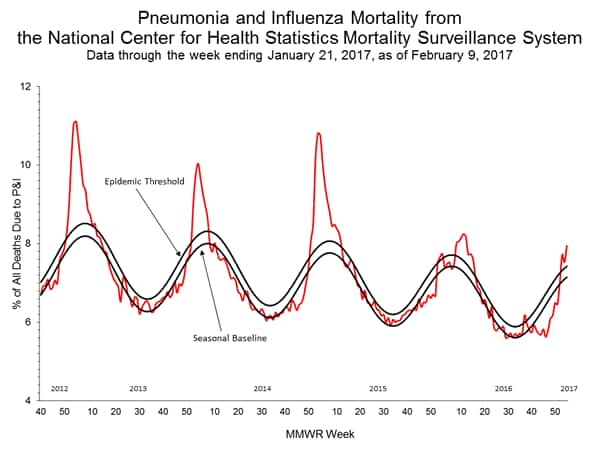

- Pneumonia and Influenza Mortality: The proportion of deaths attributed to pneumonia and influenza (P&I) was above the system-specific epidemic threshold in the National Center for Health Statistics (NCHS) Mortality Surveillance System.

- Influenza-associated Pediatric Deaths: Five influenza-associated pediatric deaths were reported.

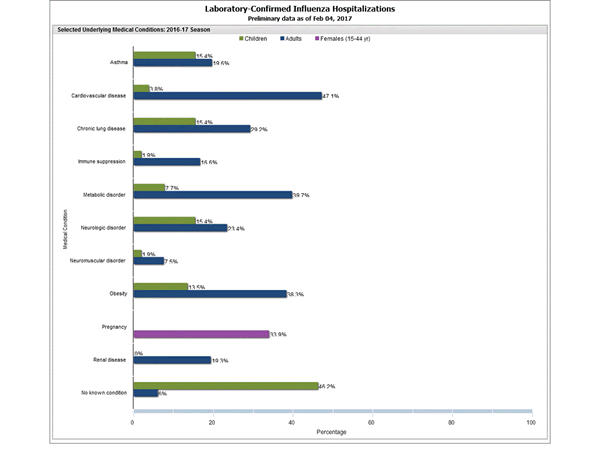

- Influenza-associated Hospitalizations: A cumulative rate for the season of 24.3 laboratory-confirmed influenza-associated hospitalizations per 100,000 population was reported.

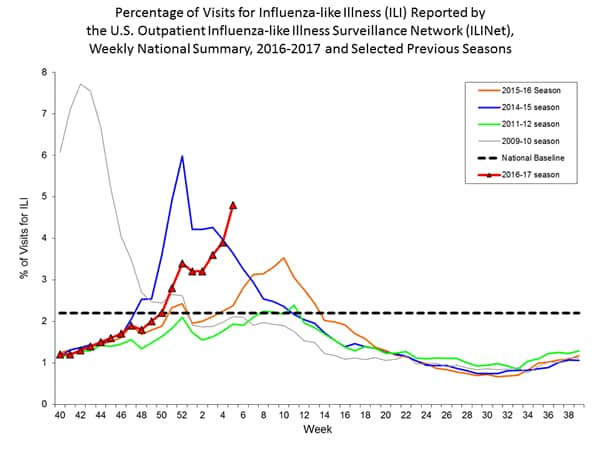

- Outpatient Illness Surveillance:The proportion of outpatient visits for influenza-like illness (ILI) was 4.8%, which is above the national baseline of 2.2%. All 10 regions reported ILI at or above their region-specific baseline levels. New York City and 23 states experienced high ILI activity; 10 states experienced moderate ILI activity; Puerto Rico and eight states experienced low ILI activity; nine states experienced minimal ILI activity; and the District of Columbia had insufficient data.

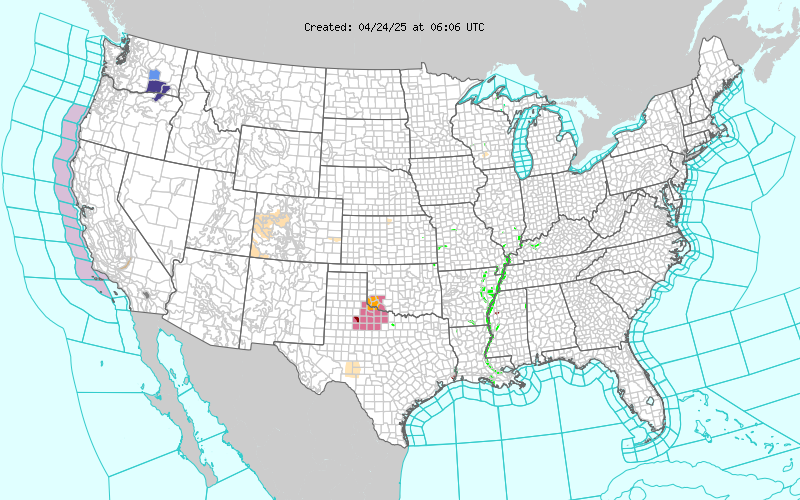

- Geographic Spread of Influenza: The geographic spread of influenza in Puerto Rico and 43 states was reported as widespread; Guam and six states reported regional activity; the District of Columbia and one state reported local activity; and the U.S. Virgin Islands reported no activity.

A powerful nighttime earthquake in the southern Philippines killed at least six people and injured more than 120 others.

Saturday, February 11th, 2017https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=qMlSJdWlA6M

Seismotectonics of the Philippine Sea and Vicinity

The Philippine Sea plate is bordered by the larger Pacific and Eurasia plates and the smaller Sunda plate. The Philippine Sea plate is unusual in that its borders are nearly all zones of plate convergence. The Pacific plate is subducted into the mantle, south of Japan, beneath the Izu-Bonin and Mariana island arcs, which extend more than 3,000 km along the eastern margin of the Philippine Sea plate. This subduction zone is characterized by rapid plate convergence and high-level seismicity extending to depths of over 600 km. In spite of this extensive zone of plate convergence, the plate interface has been associated with few great (M>8.0) ‘megathrust’ earthquakes. This low seismic energy release is thought to result from weak coupling along the plate interface (Scholz and Campos, 1995). These convergent plate margins are also associated with unusual zones of back-arc extension (along with resulting seismic activity) that decouple the volcanic island arcs from the remainder of the Philippine Sea Plate (Karig et al., 1978; Klaus et al., 1992).

South of the Mariana arc, the Pacific plate is subducted beneath the Yap Islands along the Yap trench. The long zone of Pacific plate subduction at the eastern margin of the Philippine Sea Plate is responsible for the generation of the deep Izu-Bonin, Mariana, and Yap trenches as well as parallel chains of islands and volcanoes, typical of circum-pacific island arcs. Similarly, the northwestern margin of the Philippine Sea plate is subducting beneath the Eurasia plate along a convergent zone, extending from southern Honshu to the northeastern coast of Taiwan, manifested by the Ryukyu Islands and the Nansei-Shoto (Ryukyu) trench. The Ryukyu Subduction Zone is associated with a similar zone of back-arc extension, the Okinawa Trough. At Taiwan, the plate boundary is characterized by a zone of arc-continent collision, whereby the northern end of the Luzon island arc is colliding with the buoyant crust of the Eurasia continental margin offshore China.

Along its western margin, the Philippine Sea plate is associated with a zone of oblique convergence with the Sunda Plate. This highly active convergent plate boundary extends along both sides the Philippine Islands, from Luzon in the north to the Celebes Islands in the south. The tectonic setting of the Philippines is unusual in several respects: it is characterized by opposite-facing subduction systems on its east and west sides; the archipelago is cut by a major transform fault, the Philippine Fault; and the arc complex itself is marked by active volcanism, faulting, and high seismic activity. Subduction of the Philippine Sea Plate occurs at the eastern margin of the archipelago along the Philippine Trench and its northern extension, the East Luzon Trough. The East Luzon Trough is thought to be an unusual example of a subduction zone in the process of formation, as the Philippine Trench system gradually extends northward (Hamburger et al., 1983). On the west side of Luzon, the Sunda Plate subducts eastward along a series of trenches, including the Manila Trench in the north, the smaller less well-developed Negros Trench in the central Philippines, and the Sulu and Cotabato trenches in the south (Cardwell et al., 1980). At its northern and southern terminations, subduction at the Manila Trench is interrupted by arc-continent collision, between the northern Philippine arc and the Eurasian continental margin at Taiwan and between the Sulu-Borneo Block and Luzon at the island of Mindoro. The Philippine fault, which extends over 1,200 km within the Philippine arc, is seismically active. The fault has been associated with major historical earthquakes, including the destructive M7.6 Luzon earthquake of 1990 (Yoshida and Abe, 1992). A number of other active intra-arc fault systems are associated with high seismic activity, including the Cotabato Fault and the Verde Passage-Sibuyan Sea Fault (Galgana et al., 2007).

Relative plate motion vectors near the Philippines (about 80 mm/yr) is oblique to the plate boundary along the two plate margins of central Luzon, where it is partitioned into orthogonal plate convergence along the trenches and nearly pure translational motion along the Philippine Fault (Barrier et al., 1991). Profiles B and C reveal evidence of opposing inclined seismic zones at intermediate depths (roughly 70-300 km) and complex tectonics at the surface along the Philippine Fault.

Several relevant tectonic elements, plate boundaries and active volcanoes, provide a context for the seismicity presented on the main map. The plate boundaries are most accurate along the axis of the trenches and more diffuse or speculative in the South China Sea and Lesser Sunda Islands. The active volcanic arcs (Siebert and Simkin, 2002) follow the Izu, Volcano, Mariana, and Ryukyu island chains and the main Philippine islands parallel to the Manila, Negros, Cotabato, and Philippine trenches.

Seismic activity along the boundaries of the Philippine Sea Plate (Allen et al., 2009) has produced 7 great (M>8.0) earthquakes and 250 large (M>7) events. Among the most destructive events were the 1923 Kanto, the 1948 Fukui and the 1995 Kobe (Japan) earthquakes (99,000, 5,100, and 6,400 casualties, respectively), the 1935 and the 1999 Chi-Chi (Taiwan) earthquakes (3,300 and 2,500 casualties, respectively), and the 1976 M7.6 Moro Gulf and 1990 M7.6 Luzon (Philippines) earthquakes (7,100 and 2,400 casualties, respectively). There have also been a number of tsunami-generating events in the region, including the Moro Gulf earthquake, whose tsunami resulted in more than 5000 deaths.

Diphtheria in Venezuela: Eliannys’ story is also one of misdiagnoses and missed signals worsened by government secrecy around the disease.

Saturday, February 11th, 2017Diphtheria once was a major cause of illness and death among children. The United States recorded 206,000 cases of diphtheria in 1921, resulting in 15,520 deaths. Starting in the 1920s, diphtheria rates dropped quickly due to the widespread use of vaccines. Between 2004 and 2015, 2 cases of diphtheria were recorded in the United States. However, the disease continues to cause illness globally. In 2014, 7,321 cases of diphtheria were reported worldwide to the World Health Organization, but many more cases likely go unreported.

The case-fatality rate for diphtheria has changed very little during the last 50 years. The overall case-fatality rate for diphtheria is 5%–10%, with higher death rates (up to 20%) among persons younger than 5 and older than 40 years of age. Before there was treatment for diphtheria, the disease was fatal in up to half of cases.

Clinical Features

The incubation period of diphtheria is 2–5 days (range: 1–10 days). Diphtheria can involve almost any mucous membrane. For clinical purposes, it is convenient to classify diphtheria into a number of manifestations, depending on the site of disease:

- Respiratory diphtheria

- Nasal diphtheria

- Pharyngeal and tonsillar diphtheria

- Laryngeal diphtheria

- Cutaneous diphtheria

Clinician Resources

Medical Management

After the provisional clinical diagnosis is made and appropriate cultures are obtained, persons with suspected diphtheria should be given antitoxin and antibiotics in adequate dosage and placed in isolation. Respiratory support and airway maintenance should also be administered as needed.

Diphtheria Antitoxin

In the United States, diphtheria antitoxin can be obtained from CDC on request.

Antibiotics

The recommended antibiotic treatment for diphtheria is erythromycin orally or by injection (40 mg/kg/day; maximum, 2 gm/day) for 14 days, or procaine penicillin G daily, intramuscularly (300,000 units every 12 hours for those weighing 10 kg or less, and 600,000 units every 12 hours for those weighing more than 10 kg) for 14 days. Oral penicillin V 250 mg 4 times daily is given instead of injections to persons who can swallow. The disease is usually not contagious 48 hours after antibiotics are instituted. Elimination of the organism should be documented by two consecutive negative cultures after therapy is completed.

Preventive Measures

For close contacts, especially household contacts, a diphtheria toxoid booster, appropriate for age, should be given. Contacts should also receive antibiotics—a 7- to 10-day course of oral erythromycin (40 mg/kg/day for children and 1 g/day for adults). For compliance reasons, if surveillance of contacts cannot be maintained, they should receive benzathine penicillin (600,000 units for persons younger than 6 years old and 1,200,000 units for those 6 years and older). Identified carriers in the community should also receive antibiotics. Contacts should be closely monitored and antitoxin given at the first sign(s) of illness.

Contacts of cutaneous diphtheria should be treated as described above; however, if the strain is shown to be nontoxigenic, investigation of contacts can be discontinued.

Challenges

Circulation of the bacteria appears to continue in some settings, even in populations with more than 80% childhood immunization rates. An asymptomatic carrier state can exist even among immune individuals.

Immunity wanes over time and a booster dose of vaccine should be administered every 10 years to maintain protective antibody levels. Large populations of older adults may be susceptible to diphtheria, in both developed as well as in developing countries.

In countries with low disease incidence, the diagnosis may not be considered by clinicians and laboratory scientists. Prior antibiotic treatment can prevent recovery of the organism. Because the disease is rarely seen in developed countries, most physicians will never have seen a case of diphtheria in their lifetime. There is limited epidemiologic, clinical, and laboratory expertise on diphtheria.

Surveillance

National surveillance is conducted through the National Notifiable Diseases Surveillance System. Cases are also identified by requests for diphtheria antitoxin (DAT); since 1997, DAT is available for U.S. healthcare professionals only through CDC.

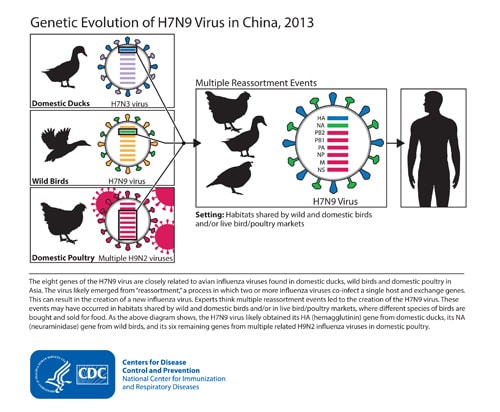

6 more H7N9 infections in 5 different provinces in China, signaling an ongoing surge of activity what will likely make the current fifth wave of illnesses the largest since the virus was first detected in humans in 2013.

Friday, February 10th, 2017H7N9 Outbreak Characterization

- H7N9 infections in people and poultry in China

- Sporadic infections in people; most with poultry exposure

- Rare limited person-to-person spread

- No sustained or community transmission

A new study indicates that the antiviral drug oseltamivir can reduce influenza infections and prevent deaths in a cost-saving manner under most pandemic scenarios.

Friday, February 10th, 2017British Journal of Clinical Pharmacology

“…..Results

Oseltamivir 75 mg relative to no treatment reduced the median number of infected patients, increased ΔQALY by deaths averted, and was cost-saving under all scenarios; 150 mg relative to 75 mg was not cost effective in low transmissibility scenarios but was cost saving in high transmissibility scenarios……”

Nepal: Almost all isolates of Acinetobacter baumannii were found to be resistant to multiple antibiotics

Friday, February 10th, 2017Co-existence of bla OXA-23 and bla NDM-1 genes of Acinetobacter baumannii isolated from Nepal: antimicrobial resistance and clinical significance

DOI: 10.1186/s13756-017-0180-5

“…..Nepalese researchers analyzed 44 isolates of A baumannii, an increasingly important pathogen. The found that 43 (98%) were resistant to carbapenems….. The same number of isolates were multidrug resistant, but all were susceptible to colistin. The bla-OXA-23 gene was detected in all of the isolates, while the New Delhi Metallo-beta-lactamase-1 (NDM-1) gene was identified in 6 (14%)……”

A new study describes a novel combination therapy that could serve as a weapon against a growing antibiotic resistance threat.

Thursday, February 9th, 2017Antimicrobial Agents and Chemotherapy

“….Ceftazidime/avibactam, which was approved in the United States in 2015, has been a valuable tool for treating certain multidrug-resistant gram-negative infections. It works by inhibiting class A and class C bacterial enzymes, such as extended-spectrum beta lactamases (ESBLs), Klebsiella pneumoniae producing carbapenemases (KPCs), and cephalosporinases, which confer resistance to beta-lactam antibiotics.

But ceftazidime/avibactam has a significant weakness: metallo-beta-lactamase enzymes, which have emerged as a significant global antibiotic resistance threat, particularly in Southeast Asia and parts of Europe. Aztreonam, on the other hand, is susceptible to the class A and C beta-lactamases but isn’t broken down by metallo-beta-lactamases.

What Bonomo and his team hypothesized was that if aztreonam were added to the ceftazidime/avibactam combination therapy, the duo would help free aztreonam to work against infection-causing bacteria by protecting it from the other beta-lactamase enzymes, like offensive lineman in football blocking for a running back…..”

Abstract

Based upon knowledge of the hydrolytic profile of major β-lactamases found in Gram negative bacteria, we tested the effectiveness of the combination of ceftazidime/avibactam (CAZ/AVI) with aztreonam (ATM) against carbapenem-resistant enteric bacteria possessing metallo-β-lactamases (MBLs). Disk-diffusion and agar based antimicrobial susceptibility testing were initially performed to determine the in vitro efficacy of a unique combination of CAZ/AVI and ATM against 21 representative Enterobacteriaceae isolates with a complex molecular background that included blaIMP, blaNDM, blaOXA-48, blaCTX-M, blaAmpC, and combinations thereof. Time-kill assays were conducted, and the in vivo efficacy of this combination was assessed in a murine neutropenic thigh infection model. By disk diffusion assay, all 21 isolates were resistant to CAZ/AVI alone, and 19/21 were resistant to ATM. The in vitro activity of CAZ/AVI in combination with ATM against diverse Enterobacteriaceae possessing MBLs was demonstrated in 17/21 isolates, where the zone of inhibition was ≥ 21 mm. All isolates demonstrated a reduction in CAZ/AVI agar dilution MICs with the addition of ATM. At 2 h, time-kill assays demonstrated a ≥ 4 log10 CFU decrease for all groups that had CAZ/AVI plus ATM (8 μg/ml) added, compared to the CAZ/AVI alone group. In the murine neutropenic thigh infection model, an almost 4 log10 reduction in CFUs was noted at 24 h for CAZ/AVI (32 mg/kg q8h) plus ATM (32 mg/kg q8h) vs. CAZ/AVI (32 mg/kg q8h) alone. The data presented herein, requires us to carefully consider this new therapeutic combination to treat infections caused by MBL-producing Enterobacteriaceae.

Terrorists Call for Attacks on Hospitals, Healthcare Facilities

Thursday, February 9th, 20178 February 2017

(U–FOUO) FL -Terrorists Call for__ Attacks on Hospitals, Healthcare Facil…

Recent calls over the past year for attacks on hospitals in the West by media outlets sympathetic to the Islamic State of

Iraq and ash-Sham (ISIS) highlight terrorists’ perception of hospitals as viable targets for attack. Targeting hospitals and healthcare facilities is consistent with ISIS’s tactics in Iraq and Syria, its previous calls for attacks on hospitals in the West, and the group’s calls for attacks in the West using “all available means.” While we have not seen any specific, credible threat against hospitals and healthcare facilities in the United States, we remain concerned that calls for such attacks may resonate with some violent extremists and lone offenders (DHS and the FBI define a lone offender as an individual motivated by one or more violent extremist ideologies who, operating alone, supports or engages in acts of violence in furtherance of that ideology or ideologies that may involve influence from a larger terrorist organization or a foreign actor.) in the Homeland because of their likely perceived vulnerabilities and value as targets.*

The pro-ISIS Nashir Media Foundation released a series of messages on 29 December 2016 encouraging lone

offenders in the West to conduct attacks on hospitals, cinemas, and malls.2

In early

June 2016, ISIS called for a “month of calamity,” encouraging followers in Europe and the

United States to attack schools and hospitals in an audio message released via Twitter.3

Additionally, in its January 2016 issue of Rumiyah magazine, ISIS provided tactical

guidance and encouraged lone offenders to conduct arson attacks on hospitals.4

» (U) ISIS, through its Amaq news agency in November 2016, took credit for an attack on

a hospital in Quetta, Pakistan that resulted in at least 74 deaths and 100 injuries.5,6,7 Aid

organizations and coalition governments have alleged since early 2015 that ISIS has

systematically targeted hospitals, healthcare facilities, patients, and healthcare workers in

Iraq and Syria, resulting in hundreds of deaths and injuries and reducing the overall

capacity of healthcare delivery infrastructure.8-12

Possible Indicators of the Targeting of Hospitals and Healthcare Facilities

(U//FOUO) Some of these activities may be constitutionally protected, and any determination of possible illicit intent should be supported by

additional facts justifying reasonable suspicion. These activities are general in nature and any one may be insignificant on its own, but when

observed in combination with other suspicious behaviors—particularly advocacy of violence—they may constitute a basis for reporting.

» (U//FOUO) Consumption and sharing of media glorifying violent extremist acts in attempting to mobilize others to violence;

» (U//FOUO) Loitering, parking, standing, or unattended vehicles in the same area over multiple days with no reasonable explanation, particularly in concealed locations with optimal visibility of potential targets or in conjunction with multiple visits;

» (U//FOUO) Photography or videography focused on security features, including cameras, security personnel, gates, and barriers;

» (U//FOUO) Unusual or prolonged interest in or attempts to gain sensitive information about security measures of personnel, entry points,

peak days and hours of operation, and access controls such as alarms or locks;

» (U//FOUO) Individuals wearing bulky clothing or clothing inconsistent with the weather or season, or wearing official uniforms or being in authorizedized areas without official credentials;

» (U//FOUO) Individuals presenting injuries consistent with the use of explosives or explosive material without a reasonable explanation; and

» (U//FOUO) Unattended packages, bags, and suitcases.

(U) Possible Mitigation Strategies

» (U//FOUO) Limit access in restricted areas and require employees to wear clearly visible identifications at all times;

» (U//FOUO) Ensure personnel receive training and briefings on active shooter preparedness, lockdown procedures, improvised explosive

device (IED) and vehicle-borne IED awareness and recognition, and suspicious activity reporting procedures; and

» (U//FOUO) Conduct law enforcement and security officer patrols in loading, waiting, and patient triage areas, and around drop-off and

pick-up points where there are large numbers of people concentrated in restricted spaces.

1 (U); Laura Connor; The Daily Mirror; “ISIS claims responsibility for Pakistan hospital bomb attack that killed at least 70 people”; 09 AUG 2016;

http://www.mirror.co.uk/news/uk-news/isis-claims-responsibility-pakistan-hospital-8592185; accessed on 27 JAN 2017.

2 (U); Julian Robinson; Daily Mail Online; “’We will make New Year mayhem’: ISIS supporters call for lone wolf attacks in cinemas, malls and

HOSPITALS as they release pictures of a knife-wielding fanatic chasing Santa Claus”; 29 DEC 2016; http://www.dailymail.co.uk/news/article-

4072998/We-make-New-Year-mayhem-ISIS-supporters-call-lone-wolf-attacks-cinemas-malls-HOSPITALS-release-pictures-knife-wieldingfanatic-

chasing-Santa-Claus.html; accessed on 04 JAN 2017.

3 (U); Thomas Burrows; Daily Mail Online; “Brussels is facing a wave of terror attacks on schools and hospitals during Ramadan, say security

services”; 14 JUN 2016; http://www.dailymail.co.uk/news/article-3640607/Brussels-facing-wave-terror-attacks-schools-hospitals-Ramadansay-

security-services.html; accessed on 04 JAN 2017.

4 (U); ISIS; Rumiyah Magazine, Issue 5; al-Hayyat Media; 06 JAN 2017; pgs. 9-10.

5 (U); Gul Yousafzai; Reuters; “Suicide bomber kills at least 70 at Pakistan hospital, IS claims responsibility”; 08 AUG 2016;

http://www.reuters.com/article/us-pakistan-blast-idUSKCN10J0I7; accessed on 29 DEC 2016.

6 (U); Samuel Osborne; The Independent; “Where are the hashtags for the Pakistan hospital attack? Lack of response to bombing criticised on

Twitter”; 09 AUG 2016; http://www.independent.co.uk/news/world/asia/pakistan-hospital-bomb-attack-isis-taliban-behind-death-tolla7180151.

html; accessed on 29 DEC 2016.

7 (U); Salman Masood; The New York Times; “Suicide Bomber Kills Dozens at Pakistani Hospital in Quetta”; 08 AUG 2016;

http://www.nytimes.com/2016/08/09/world/asia/quetta-pakistan-blast-hospital.html?_r=0; accessed on 04 JAN 2017.

8 (U); Roy Gutman; PBS; “In Recent Months, ISIS Targeted Hospitals, Doctors, Journalists”; 11 FEB 2014;

http://www.pbs.org/wgbh/frontline/article/in-recent-months-isis-targeted-hospitals-doctors-journalists/; accessed on 29 DEC 2016.

9 (U); Newsweek (Reuters); “ISIS Attacks Hospital in Dawn Raid on Syrian City”; 14 MAY 2016; http://www.newsweek.com/isis-attackshospital-

syrian-city-459961; accessed on 29 DEC 2016.

10 (U); WHO Regional Office for the Eastern Mediterranean; “WHO condemns attack on Jableh hospital in Syria”; 23 MAY 2016;

http://www.emro.who.int/media/news/who-condemns-attack-on-jableh-hospital-in-syria.html; accessed on 30 DEC 2016; (U); World Health

Organization website.

11 (U); CBC News (Thompson Reuters); “Syria bombings claimed by ISIS kill 148 at hospital, bus station”; 23 MAY 2016;

http://www.cbc.ca/news/politics/syria-isis-bombings-1.3596282; accessed on 30 DEC 2016.

12 (U); Sylvia Westall, Kara O’Neill; Mirror Online; “ISIS suicide bomber blows himself up in crowd just moments after detonating car bomb

near hospital”; 15 DEC 2015; http://www.mirror.co.uk/news/world-news/isis-suicide-bomber-blows-himself-7016256; accessed on 30 DEC

2016.

Significant winter storm possible from the Middle Atlantic to New England

Wednesday, February 8th, 2017Low pressure is forecast to develop into a coastal storm and bring significant impacts from portions of the Middle Atlantic to New England late Wednesday into Thursday. The potential exists for heavy snow and dangerous travel conditions including the major interstate 95 cities from Philadelphia to New York City and Boston.