Archive for March, 2017

Zika Virus continues in Florida

Monday, March 6th, 2017March 02, 2017

Department of Health Daily Zika Update

Contact:

Communications Office

NewsMedia@flhealth.gov

(850) 245-4111

Tallahassee, Fla. — In an effort to keep Florida residents and visitors safe and aware about the status of the Zika virus, the department issues a Zika virus update when there is a confirmed locally acquired case of Zika.

There are no new travel-related cases to report today. Please visit our website to see the full list of travel-related cases by county and year. The department updates the travel-related case chart online each weekday.

There are three locally acquired cases being reported today. Two are cases that had samples collected in October as part of our ongoing investigation and the department just received confirmatory testing back from CDC. These two cases have been added to the 2016 chart.

The third case reported no symptoms, but screening conducted after blood donation in January showed evidence of a past infection. The department concluded our investigation of this case yesterday. This individual had multiple exposures in Miami-Dade County and likely contracted Zika in 2016. Because the individual was asymptomatic, it is difficult to determine when infection occurred. Since the first positive sample was collected in January, this is considered our first locally reported case of Zika in 2017. Florida still does not have any identified areas with ongoing, active Zika transmission.

The total number of Zika cases reported in Florida for 2016 is 1,384. The total number of Zika cases reported in Florida for 2017 is 18.

2016

| Infection Type | Infection Count |

| Travel-Related Infections Of Zika | 1076 |

| Locally Acquired Infections Of Zika | 276 |

| Undetermined | 32 |

| . | |

| Pregnant Women With Lab-Evidence Of Zika | 264 |

2017

| Infection Type | Infection Count |

| Travel-Related Infections Of Zika | 13 |

| Locally Acquired Infections Of Zika | 1 |

| Undetermined | 0 |

| . | |

| Pregnant Women With Lab-Evidence Of Zika | 4 |

Florida no longer has any identified areas with active Zika transmission, but we will continue to see isolated cases of local transmission so it is important for residents and visitors in Miami-Dade County to remain vigilant about mosquito bite protection.

It is important for people to remember to take proper precautions to prevent mosquito bites while traveling to areas with widespread Zika transmission. The CDC list of these locations is available here.

One case does not mean ongoing active transmission is taking place. DOH conducts a thorough investigation by sampling close contacts and community members around each case to determine if additional people are infected. If DOH finds evidence that active transmission is occurring in an area, the media and the public will be notified.

The department has conducted Zika virus testing for more than 12,700 people statewide. Florida currently has the capacity to test 4,653 people for active Zika virus and 5,152 for Zika antibodies. At Governor Scott’s direction, all county health departments now offer free Zika risk assessment and testing to pregnant women.

The CDC advises pregnant women should consider postponing travel to Miami-Dade County. If you are pregnant and must travel or if you live or work in Miami-Dade County, protect yourself from mosquito bites by wearing insect repellent, long clothing and limiting your time outdoors.

According to CDC guidance, providers should test all pregnant women who lived in, traveled to or whose partner traveled to Miami-Dade County after Aug. 1, 2016. Pregnant women in Miami-Dade County can contact their medical provider or their local county health department to be tested and receive a Zika prevention kit. Additionally, the department is working closely with the Healthy Start Coalition of Miami-Dade County to identify pregnant women in Miami-Dade County to ensure they have access to resources and information to protect themselves. CDC recommends that a pregnant woman with a history of Zika virus and her provider should consider additional ultrasounds.

Pregnant women can contact their local county health department for Zika risk assessment and testing hours and information. A Zika risk assessment will be conducted by county health department staff and blood and/or urine samples may be collected and sent to labs for testing. It may take one to two weeks to receive results.

Florida has been monitoring pregnant women with evidence of Zika regardless of symptoms. The total number of pregnant women who have been or are being monitored is 264.

On Feb. 12, Governor Scott directed the State Surgeon General to activate a Zika Virus Information Hotline for current Florida residents and visitors, as well as anyone planning on traveling to Florida in the near future. The number for the Zika Virus Information Hotline is 1-855-622-6735.

The department urges Floridians to drain standing water weekly, no matter how seemingly small. A couple drops of water in a bottle cap can be a breeding location for mosquitoes. Residents and visitors also need to use repellents when enjoying the Florida outdoors.

For more information on DOH action and federal guidance, please click here.

For resources and information on Zika virus, click here.

About the Florida Department of Health

The department, nationally accredited by the Public Health Accreditation Board, works to protect, promote and improve the health of all people in Florida through integrated state, county and community efforts.

Follow us on Twitter at @HealthyFla and on Facebook. For more information about the Florida Department of Health please visit www.FloridaHealth.gov.

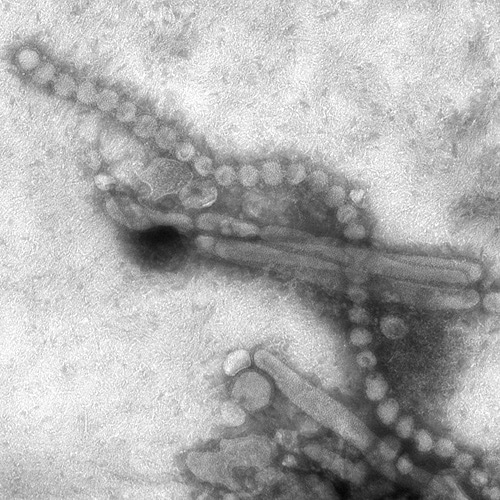

U.S. officials say of all emerging influenza viruses, H7N9 currently poses the greatest risk of a pandemic threat if it evolves to spread readily from human to human.

Sunday, March 5th, 2017“….Centers for Disease Control and Prevention officials are developing a vaccine that would target a newly evolving version of the virus….”

At least 110 people, most of them women and children, have died from starvation and drought-related illness in Somalia in the past 48 hours.

Sunday, March 5th, 2017CDC: Multistate STEC O157:H7 outbreak tied to nut butter

Saturday, March 4th, 2017

Highlights

- CDC, multiple states, and the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) are investigating a multistate outbreak of Shiga toxin-producing Escherichia coli(https://www.cdc.gov/ecoli/general/index.html) O157:H7 (STEC O157:H7) infections.

- Twelve people infected with the outbreak strain of STEC O157:H7 have been reported from five states.

- Six ill people have been hospitalized. Four people developed hemolytic uremic syndrome, a type of kidney failure, and no deaths have been reported.

- Eleven of the 12 ill people in this outbreak are younger than 18 years old.

- Epidemiologic evidence available at this time indicates that I.M. Healthy brand SoyNut Butter is a likely source of this outbreak. I.M. Healthy brand SoyNut Butter may be contaminated with E. coli O157:H7 and could make people sick.

- CDC recommends that consumers do not eat, and childcare centers, schools, and other institutions do not serve, any I.M. Healthy brand SoyNut Butter varieties and sizes, or I.M. Healthy brand granola coated with SoyNut Butter.

- Even if some of the SoyNut Butter or granola was eaten or served and no one got sick, throw the rest of the product away. Put it in a sealed bag in the trash so that children, pets, or other animals can’t eat it.

- This investigation is ongoing and quickly changing. CDC will provide updates as more information becomes available.

H7N9: 21 more fall ill in China over past week

Saturday, March 4th, 2017CHP notified of human cases of avian influenza A(H7N9) in Mainland

The Centre for Health Protection (CHP) of the Department of Health today (March 3) received notification from the National Health and Family Planning Commission that 21 additional human cases of avian influenza A(H7N9), including three deaths, were recorded from February 24 to March 2. The CHP strongly urges the public to maintain strict personal, food and environmental hygiene both locally and during travel.

The 17 male and four female patients, aged from 10 to 77, had their onset from February 10 to 27. The cases were from Guangdong (six cases), Anhui (four cases), Jiangsu (three cases), two cases each in Guangxi and Jiangxi, and one case each in Hubei, Hunan, Shanghai and Zhejiang. Among them, 18 were known to have exposure to poultry or poultry markets.

Of note, according to the surveillance of the Guangdong Provincial Center for Disease Control and Prevention, from February 22 to 28, among 855 environmental samples collected from 89 markets in various areas in Guangdong, 83 samples from 27 markets tested positive for H7 virus, i.e. about 30 per cent of the markets in Guangdong and 9.7 per cent of the samples were positive.

Travelers to the Mainland or other affected areas must avoid visiting wet markets, live poultry markets or farms. They should be alert to the presence of backyard poultry when visiting relatives and friends. They should also avoid purchase of live or freshly slaughtered poultry, and avoid touching poultry/birds or their droppings. They should strictly observe personal and hand hygiene when visiting any place with live poultry.

Travelers returning from affected areas should consult a doctor promptly if symptoms develop, and inform the doctor of their travel history for prompt diagnosis and treatment of potential diseases. It is essential to tell the doctor if they have seen any live poultry during travel, which may imply possible exposure to contaminated environments. This will enable the doctor to assess the possibility of avian influenza and arrange necessary investigations and appropriate treatment in a timely manner.

While local surveillance, prevention and control measures are in place, the CHP will remain vigilant and work closely with the World Health Organization and relevant health authorities to monitor the latest developments.

The CHP’s Port Health Office conducts health surveillance measures at all boundary control points. Thermal imaging systems are in place for body temperature checks on inbound travellers. Suspected cases will be immediately referred to public hospitals for follow-up.

The display of posters and broadcasting of health messages in departure and arrival halls as health education for travellers is under way. The travel industry and other stakeholders are regularly updated on the latest information.

The public should maintain strict personal, hand, food and environmental hygiene and take heed of the advice below while handling poultry:

- Avoid touching poultry, birds, animals or their droppings;

- When buying live chickens, do not touch them and their droppings. Do not blow at their bottoms. Wash eggs with detergent if soiled with faecal matter and cook and consume them immediately. Always wash hands thoroughly with soap and water after handling chickens and eggs;

- Eggs should be cooked well until the white and yolk become firm. Do not eat raw eggs or dip cooked food into any sauce with raw eggs. Poultry should be cooked thoroughly. If there is pinkish juice running from the cooked poultry or the middle part of its bone is still red, the poultry should be cooked again until fully done;

- Wash hands frequently, especially before touching the mouth, nose or eyes, before handling food or eating, and after going to the toilet, touching public installations or equipment such as escalator handrails, elevator control panels or door knobs, or when hands are dirtied by respiratory secretions after coughing or sneezing; and

- Wear a mask if fever or respiratory symptoms develop, when going to a hospital or clinic, or while taking care of patients with fever or respiratory symptoms.

The public may visit the CHP’s pages for more information: the avian influenza page, the weekly Avian Influenza Report, global statistics and affected areas of avian influenza, the Facebook Page and the YouTube Channel.

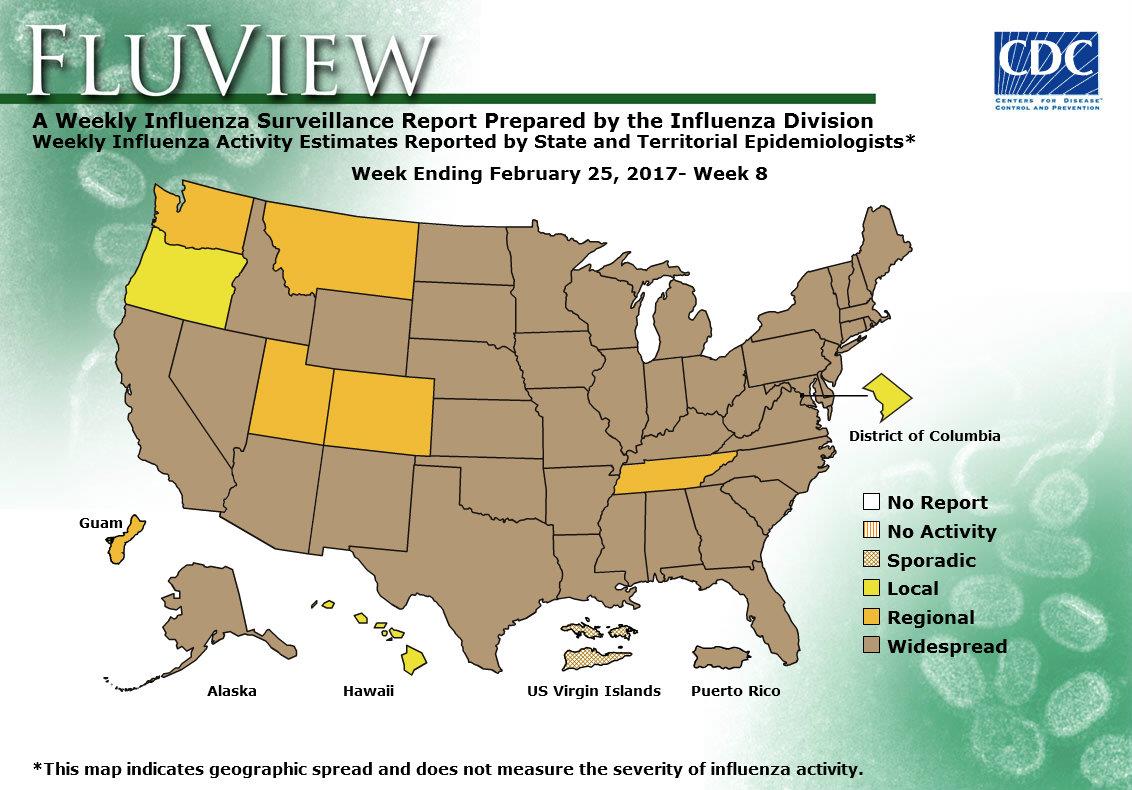

2016-2017 Influenza Season Week 8 ending February 25, 2017: Influenza activity remains elevated in the United States.

Saturday, March 4th, 2017During week 8 (February 19-25 2017), influenza activity remained elevated in the United States.

- Viral Surveillance: The most frequently identified influenza virus subtype reported by public health laboratories during week 8 was influenza A (H3). The percentage of respiratory specimens testing positive for influenza in clinical laboratories remained elevated.

- Pneumonia and Influenza Mortality: The proportion of deaths attributed to pneumonia and influenza (P&I) was above the system-specific epidemic threshold in the National Center for Health Statistics (NCHS) Mortality Surveillance System.

- Influenza-associated Pediatric Deaths: Six influenza-associated pediatric deaths were reported.

- Influenza-associated Hospitalizations: A cumulative rate for the season of 39.4 laboratory-confirmed influenza-associated hospitalizations per 100,000 population was reported.

- Outpatient Illness Surveillance: The proportion of outpatient visits for influenza-like illness (ILI) was 4.8%, which is above the national baseline of 2.2%. All 10 regions reported ILI at or above their region-specific baseline levels. 27 states experienced high ILI activity; four states experienced moderate ILI activity; New York City, Puerto Rico and six states experienced low ILI activity; 13 states experienced minimal ILI activity; and the District of Columbia had insufficient data.

- Geographic Spread of Influenza: The geographic spread of influenza in Puerto Rico and 43 states was reported as widespread; Guam and five states reported regional activity; the District of Columbia and two states reported local activity; and the U.S. Virgin Islands reported sporadic activity.

Response to a Large Polio Outbreak in a Setting of Conflict — Middle East, 2013–2015

Saturday, March 4th, 2017Chukwuma Mbaeyi, DDS1; Michael J. Ryan, MD2; Philip Smith, MD2; Abdirahman Mahamud, MD2; Noha Farag, MD, PhD1; Salah Haithami, MD2; Magdi Sharaf, MD2; Jaume C. Jorba, PhD3; Derek Ehrhardt, MPH, MSN1

Weekly / March 3, 2017 / 66(8);227–231

Summary

What is already known about this topic?Afghanistan, Nigeria, and Pakistan are the only three countries that have never interrupted endemic transmission of wild poliovirus (WPV). Continued WPV circulation in these countries poses a risk for polio outbreaks in polio-free regions of the world, especially in countries experiencing conflict and insecurity, with attendant disruption of health care and immunization services.

What is added by this report?A WPV outbreak occurred in Syria and Iraq during 2013–2014 after importation of a poliovirus strain circulating in Pakistan. The outbreak represented the first occurrence of polio cases in both countries in approximately a decade, and resulted in 38 polio cases, including 36 in Syria and two in Iraq. Development and implementation of an integrated response plan for strengthening acute flaccid paralysis surveillance and synchronized mass vaccination campaigns by eight national governments in the Middle East facilitated interruption of the outbreak within 6 months of its identification.

What are the implications for public health practice?Countries experiencing active conflict and chronic insecurity are at increased risk for polio outbreaks because of political instability and population displacement hindering delivery of immunization services. Adoption of a concerted approach to planning and implementing response activities, with involvement of more stable neighboring countries, could serve as a useful model for polio outbreak response in areas affected by conflict, as exemplified by the Middle East polio outbreak response.

As the world advances toward the eradication of polio, outbreaks of wild poliovirus (WPV) in polio-free regions pose a substantial risk to the timeline for global eradication. Countries and regions experiencing active conflict, chronic insecurity, and large-scale displacement of persons are particularly vulnerable to outbreaks because of the disruption of health care and immunization services (1). A polio outbreak occurred in the Middle East, beginning in Syria in 2013 with subsequent spread to Iraq (2). The outbreak occurred 2 years after the onset of the Syrian civil war, resulted in 38 cases, and was the first time WPV was detected in Syria in approximately a decade (3,4). The national governments of eight countries designated the outbreak a public health emergency and collaborated with partners in the Global Polio Eradication Initiative (GPEI) to develop a multiphase outbreak response plan focused on improving the quality of acute flaccid paralysis (AFP) surveillance* and administering polio vaccines to >27 million children during multiple rounds of supplementary immunization activities (SIAs).† Successful implementation of the response plan led to containment and interruption of the outbreak within 6 months of its identification. The concerted approach adopted in response to this outbreak could serve as a model for responding to polio outbreaks in settings of conflict and political instability.

Outbreak Detection and Epidemiology

Detection of the Middle East outbreak depended upon systems for AFP surveillance in the affected countries, including the World Health Organization’s (WHO’s) Early Warning, Alert and Response Network (EWARN)§, through which the outbreak was identified in October 2013. The nonpolio AFP (NPAFP) and stool adequacy rates served as indicators for assessing the ability of the affected countries to detect polio cases and also to determine when the outbreak had been interrupted.

Among countries that reported polio cases, the NPAFP rate in Syria in 2012 was 1.4 cases per 100,000 persons aged <15 years, below the recommended benchmark of ≥2. The NPAFP rate for Syria improved, increasing to 1.7 cases per 100,000 persons in 2013, the year the outbreak was detected, and to 4.0 and 3.0 in 2014 and 2015, respectively (Table). In Iraq, the NPAFP rate ranged from 3.1 to 4.0 during 2012–2015; estimates of NPAFP rates in Syria and Iraq might, however, be inaccurate because of the large-scale conflict-related displacement of persons and the attendant impact on target population estimates. Among countries at risk, NPAFP rates were suboptimal in Jordan at the onset, but improved over the course of the outbreak, increasing from 1.4 in 2013 to 3.2 in 2015. Despite incremental improvements, NPAFP rates remained <2 in Turkey over the course of the outbreak, and rates declined in Palestine from 2.2 in 2013 to 1.2 in 2014 before improving to 2.2 in 2015. All other countries involved in the response achieved recommended benchmarks.

Rates of stool specimen adequacy (i.e., receipt of two stool specimens collected at least 24 hours apart within 14 days of paralysis onset and properly shipped to the laboratory) in Syria increased from 68% in 2013 to 90% in 2015; in Iraq, rates of stool specimen adequacy exceeded the benchmark of ≥80% in each year during 2012–2015. Lebanon showed substantial gaps in stool specimen adequacy before and during the outbreak with rates ranging from 45% to 70% during 2012–2014, but the rate improved to 84% in 2015.

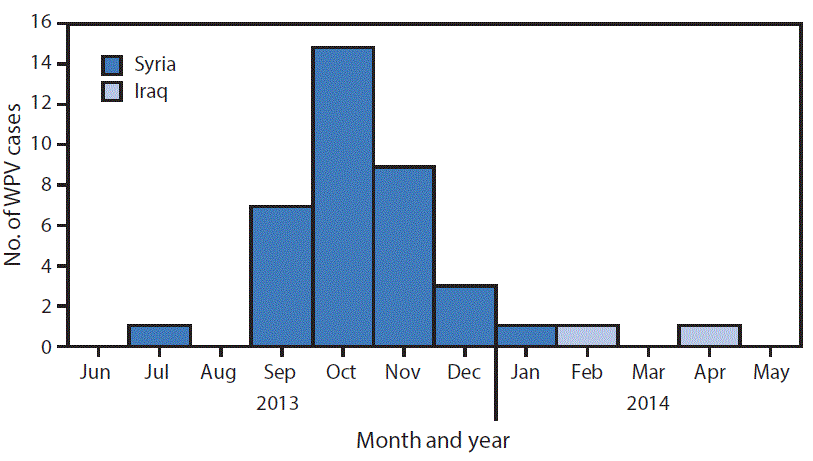

A total of 38 WPV type 1 cases were reported during the outbreak, with dates of paralysis onset ranging from July 14, 2013 for the index case (Aleppo, Syria) to April 7, 2014 for the last confirmed case (Baghdad, Iraq). The outbreak was virologically confirmed in October 2013. Of the 38 cases reported, 36 occurred in Syria and two occurred in Iraq (Figure 1). Approximately two thirds (24 of 38) of reported cases occurred in male children and 74% of cases occurred in children aged <2 years. Fifty-eight percent of children with polio had never received oral poliovirus vaccine (OPV) either through routine or supplementary immunization (i.e., zero-dose children), and an additional 37% of children with polio had received ≤3 OPV doses. The remaining 5% of children with polio had received 3 OPV doses.

Thirty-five of the 36 polio cases in Syria were reported during 2013 and the last identified case had paralysis onset in January 2014. A breakdown of cases by governorate (Figure 2) indicates that 25 (69%) cases were reported from Deirez-Zour, five from Aleppo, three from Edleb, two from Hasakeh, and one from Hama. The two cases reported from Iraq occurred in February and April 2014; both were from Baghdad-Resafa Governorate. Both cases were related by genetic sequencing and were closely linked to WPV circulating in Syria. Genetic sequencing indicated virus circulation might have begun a year earlier somewhere in the Middle East, coincident with identification of WPV-positive environmental samples in Egypt in December 2012 (5). The implicated viral strain was genetically linked to strains circulating in Pakistan (6).

Outbreak Response Plan Development

Eight countries in the region (Egypt, Iran, Iraq, Jordan, Lebanon, Palestine, Syria, and Turkey) developed a concerted Middle East polio outbreak response plan, which was updated during the course of the outbreak. Countries were grouped into two areas: 1) countries with poliovirus transmission (Syria and Iraq), and 2) countries at significant risk for poliovirus importation based on geographic proximity and influx of displaced persons from the outbreak zone (Egypt, Iran, Jordan, Lebanon, Palestine, and Turkey). The strategic response in these areas occurred in three phases. Phase I (October 2013–April 2014) focused on interrupting WPV transmission and halting spread of the virus beyond the affected countries. Phase II (May 2014–January 2015) identified areas at high risk for poliovirus importation and circulation based on stipulated criteria, including presence of refugees and mobile populations, security-compromised areas, districts with low vaccination coverage, and geographically hard-to-reach communities. These areas were prioritized for SIAs and intensified surveillance activities. Phase III (February–October 2015) was aimed at further boosting population immunity against polio through strengthened routine immunization systems and SIAs.

Immunization Coverage. Conflict in Syria and Iraq in the years preceding and following the outbreak led to steep declines in routine vaccination coverage among children in both countries, in contrast to most other countries in the Middle East where coverage remained high. Estimated national routine vaccination coverage of infants in Syria with 3 doses of oral poliovirus vaccine (OPV3) declined from preconflict levels of 83% in 2010 to 47%–52% during 2012–2014.¶ Estimates of coverage in Iraq were ≤70% and coverage in Lebanon was 75% during 2012–2014. All other countries involved in the response had coverage levels of >90% during 2012–2014.

In response to the Middle East polio outbreak, >70 SIAs were conducted during October 2013–December 2015. SIAs targeted approximately 27 million children aged <5 years in eight countries and were conducted using trivalent (types 1, 2, and 3) and bivalent (types 1 and 3) OPV. Strategies used during the campaigns included fixed-post (health facility), house-to-house visits, transit-point vaccination, and deployment of mobile teams to vulnerable populations and geographically hard-to-reach areas. Strategies were tailored to the unique sociocultural context of each country involved in the response.

Implementation of outbreak response plan. Following identification of the outbreak, Syria conducted two rounds of national immunization days (NIDs) in November and December 2013, eight NIDs and one round of subnational immunization days (SNIDs) in 2014, and four NIDs and two SNIDs in 2015 (Table). Postcampaign monitoring coverage estimates improved from 79% in December 2013 to 93% in March 2014, with coverage levels ≥88% during a majority of the campaigns. Iraq held 14 NIDs and four SNIDs as part of the response, with postcampaign monitoring coverage levels ranging from 86% to 94% during 2014. Egypt, Iran, Jordan, Lebanon, Palestine, and Turkey conducted two to 11 vaccination campaigns.

Active conflict in many parts of Syria and some parts of Iraq limited access for vaccination activities during the course of the response. Negotiations with local authorities and engagement of community leaders enabled implementation of a limited number of vaccination campaigns in some conflict-affected areas, but it was difficult to monitor these campaigns, or generate reliable data on the quality of response activities. Egypt, Iraq, Jordan, Lebanon, and Turkey received large numbers of Syrian refugees (7), which placed significant strain on their health care resources and increased costs of implementing outbreak response activities. Refugees aged <15 years living in camps in Jordan were vaccinated against polio upon registration and entry, and during special vaccination campaigns held in camps.

In assessing the effect of outbreak response activities, the vaccination status of nonpolio AFP cases in children aged 6–59 months in Syria and Iraq was reviewed. The proportion of NPAFP cases among children aged 6–59 months who were reported to have received ≥3 doses of OPV in Syria rose from 82% in 2013 to 94% in 2015, but remained at 93% among Iraqi children of the same age group during 2013–2015. The proportion of children aged 6–59 months with NPAFP who had never received OPV, or any other form of polio vaccination, decreased from 9% in 2013 to 2% in 2015 in Syria, but increased slightly from 1% to 3% in Iraq during the same period.

Discussion

The Middle East polio outbreak occurred within an extremely challenging setting, given the ongoing civil war in Syria and conflict in several parts of Iraq. The near collapse of the health care system in conflict-affected parts of Syria resulted in plummeting levels of routine vaccination coverage that left many children born after the start of the civil war unimmunized or underimmunized against polio, and set the stage for the spread of poliovirus following importation within this age group and beyond.

Actions were taken to mitigate the risk for a polio outbreak in Syria when WPV-positive environmental isolates were identified in Egypt late in 2012. AFP surveillance activities in Syria, including in opposition-controlled areas, were intensified through WHO’s EWARN system, and polio vaccination campaigns were conducted in all of Syria’s governorates by January 2013 (6). However, the cohort of children born during the conflict remained vulnerable to a polio outbreak because of steep declines in routine polio vaccination coverage.

After a cluster of WPV cases was detected in Deirez-Zour Governorate, the government of Syria immediately declared the outbreak a public health emergency. A multicountry response plan was developed to contain and interrupt the outbreak, which was effectively contained within 6 months from the time of its identification. Improvements in AFP surveillance performance indicators in the outbreak-affected countries provided a basis for WHO to declare the outbreak over in 2015. In addition to intensified surveillance and immunization activities, the response owed its success in large part to the level of collaboration and concerted approach adopted by eight national governments in the region. Another factor contributing to the success of the response was that high routine immunization coverage in many countries in the region, coupled with high prewar vaccination coverage in Syria, limited the population of vulnerable persons to mostly children born after the onset of the civil war.

With the attention of GPEI focused on the final push to interrupt indigenous WPV transmission in the remaining three polio-endemic countries (8–10), vigilance must be maintained in the Middle East and other conflict-affected areas to forestall the risk for new WPV outbreaks. In the event of a new outbreak, the Middle East polio outbreak response provides a model for an effective response within challenging settings.

* The quality of acute flaccid paralysis (AFP) surveillance is monitored by performance indicators that include 1) the detection rate of nonpolio AFP (NPAFP) cases, and 2) the proportion of AFP cases with adequate stool specimens. World Health Organization (WHO) operational targets for countries with endemic poliovirus transmission are an NPAFP detection rate of ≥2 cases per 100,000 population aged <15 years, and adequate stool specimen collection from ≥80% of AFP cases, in which two specimens are collected ≥24 hours apart, both within 14 days of paralysis onset, and shipped on ice or frozen packs to a WHO-accredited laboratory, arriving in good condition (without leakage or desiccation).

† Mass campaigns conducted for a brief period (days to weeks) in which 1 dose of oral poliovirus vaccine is administered to all children aged <5 years, regardless of vaccination history. Campaigns are conducted nationally or subnationally (i.e., in portions of the country).

§ http://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/10665/70812/1/WHO_HSE_GAR_DCE_2012_1_eng.pdf.

¶ http://apps.who.int/immunization_monitoring/globalsummary.

References

- Akil L, Ahmad HA. The recent outbreaks and reemergence of poliovirus in war- and conflict-affected areas. Int J Infect Dis 2016;49:40–6. CrossRef PubMed

- Arie S. Polio virus spreads from Syria to Iraq. BMJ 2014;348:g2481. CrossRef PubMed

- Ahmad B, Bhattacharya S. Polio eradication in Syria. Lancet Infect Dis 2014;14:547–8. CrossRef PubMed

- Aylward B. An ancient scourge triggers a modern emergency. East Mediterr Health J 2013;19:903–4. PubMed

- World Health Organization. Outbreak news. Poliovirus isolation, Egypt. Wkly Epidemiol Rec 2013;88:74–5. PubMed

- Aylward RB, Alwan A. Polio in syria. Lancet 2014;383:489–91. CrossRef PubMed

- United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees. Syria regional refugee response: inter-agency information sharing portal. Geneva, Switzerland: United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees; 2017. http://data.unhcr.org/syrianrefugees/regional.php

- Morales M, Tangermann RH, Wassilak SG. Progress toward polio eradication—worldwide, 2015–2016. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2016;65:470–3. CrossRef PubMed

- Hampton LM, Farrell M, Ramirez-Gonzalez A, et al. ; Immunization Systems Management Group of the Global Polio Eradication Initiative. Cessation of trivalent oral poliovirus vaccine and introduction of inactivated poliovirus vaccine—worldwide 2016. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2016;65:934–8. CrossRef PubMed

- Mbaeyi C, Shukla H, Smith P, et al. Progress toward poliomyelitis eradication—Afghanistan, January 2015‒August 2016. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2016;65:1195–9. CrossRef PubMed

TABLE. Acute flaccid paralysis (AFP) surveillance indicators and outbreak response activities by country and year — eight countries in the Middle East, 2012–2015

| Year/Activity | Country | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Egypt | Iran | Iraq | Jordan | Lebanon | Palestine | Syria | Turkey | |

| 2012 | ||||||||

| Nonpolio AFP rate* | 3.9 | 3.5 | 3.8 | 1.5 | 2.2 | 1.3 | 1.4 | 0.9 |

| AFP cases with adequate specimens (%) | 92 | 92 | 90 | 84 | 50 | 95 | 84 | 80 |

| 2013 | ||||||||

| Nonpolio AFP rate* | 3 | 4 | 3.1 | 1.4 | 2.2 | 2.2 | 1.7 | 1.2 |

| AFP cases with adequate specimens (%) | 92 | 96 | 84 | 91 | 45 | 95 | 68 | 76 |

| SIAs | 2 NIDs | —† | 2 NIDs | 2 NIDs | 2 NIDs | 1 NID | 2 NIDs | 2 SNIDs |

| 1 SNID | ||||||||

| 2014 | ||||||||

| Nonpolio AFP rate* | 2.9 | 4.2 | 4 | 2.5 | 2.7 | 1.2 | 4 | 1.5 |

| AFP cases with adequate specimens (%) | 93 | 96 | 89 | 97 | 70 | 90 | 84 | 77 |

| SIAs | 2 NIDs | 2 SNIDs | 7 NIDs | 3 NIDs | 4 NIDs | 1 NID | 8 NIDs | 5 SNIDs |

| 1 SNID | 3 SNIDs | 2 SNIDs | 3 SNIDs | 1 SNID | ||||

| 2015 | ||||||||

| Nonpolio AFP rate* | 3 | 4.3 | 3.6 | 3.2 | 5.2 | 2.2 | 3 | 1.7 |

| AFP cases with adequate specimens (%) | 94 | 97 | 82 | 97 | 84 | 92 | 90 | 82 |

| SIAs | 1 NID | 2 SNIDs | 5 NIDs | 1 SNID | 2 SNIDs | —† | 4 NIDs | 2 SNIDs |

| 2 SNIDs | 2 SNIDs | |||||||

Abbreviations: NIDs = national immunization days; SIAs = supplemental immunization activities; SNIDs = subnational immunization days.

* Cases per 100,000 children aged <15 years (target: ≥2 per 100,000).

† No NIDs or SNIDs conducted for the year.

FIGURE 1. Number of cases of wild poliovirus type 1 (WPV1), by month and year of paralysis onset — Syria and Iraq, 2013–2014

FIGURE 1. Number of cases of wild poliovirus type 1 (WPV1), by month and year of paralysis onset — Syria and Iraq, 2013–2014

FIGURE 2. Cases of wild poliovirus type 1 (WPV1) — Syria and Iraq, 2013–2014*

FIGURE 2. Cases of wild poliovirus type 1 (WPV1) — Syria and Iraq, 2013–2014*

* Each dot represents one case. Dots are randomly placed within second administrative units.

Suggested citation for this article: Mbaeyi C, Ryan MJ, Smith P, et al. Response to a Large Polio Outbreak in a Setting of Conflict — Middle East, 2013–2015. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2017;66:227–231. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.15585/mmwr.mm6608a6.

The mayor of Calais has banned the distribution of food to migrants as part of a campaign to prevent the establishment of a new refugee camp

Friday, March 3rd, 2017US officials charged with preparing the country for influenza pandemics conclude that the stored H7N9 vaccine doesn’t adequately protect against a new branch of this virus family, and a new vaccine is needed.

Friday, March 3rd, 2017“…the Biomedical Advanced Research and Development Authority, or BARDA, said the H7N9 vaccine in the [US Strategic National Stockpile (SNS)] would not fend off a new family of these viruses that has emerged in China, known as the eastern or Yangtze River Delta lineage of the viruses….”

- The H7N9 virus is evolving and has essentially split into two groups that are now different enough that vaccine for one might not protect very well against viruses from the other.

- The US stockpile currently contains enough vaccines to inoculate about 12 million people against the older lineage of H7N9, the southern or Pearl River Delta viruses.

- The vaccines in the pandemic flu stockpile are intended to protect first responders in the case one of the highest-risk bird flu viruses triggers a pandemic. BARDA’s policy is to maintain enough vaccine for each of these top threats to be able to vaccinate 20 million people. As each person would need both a primer and a booster dose, that means 40 million doses of vaccine for each viral threat.

“The World Health Organization’s (WHO’s) flu vaccine advisory group today recommended changing one strain—the 2009 H1N1 component—for the Northern Hemisphere’s 2017-18 flu season……Also, the advisors reviewed the latest genetic information about recent avian and other zoonotic flu viruses and recommended two new candidate vaccine viruses for H7N9 avian flu, plus three new ones for other potential pandemic threats….”

Friday, March 3rd, 2017“…..The WHO recommends the following for the Northern Hemisphere’s trivalent vaccines:

- For H1N1, an A/Michigan/45/2015-like virus

- For H3N2, an A/Hong Hong/4801/2014-like virus

- For B, Brisbane/60/2008-like virus (belonging to the Victoria lineage)

For quadrivalent versions that contain two influenza B strains, the WHO experts recommended adding Phuket/3073/2013-like virus, a Yamagata lineage virus that is the second B component of quadrivalent vaccines for both the Southern Hemisphere’s past and the Northern Hemisphere’s current season….”

“…..Today the group said that recent H7N9 viruses fall into the Yangtze River Delta (YRD) or Pearl River Delta (PRD) hemagglutinin lineages, and that two existing candidate vaccine viruses don’t seem to protect against recent YRD-lineage viruses. They proposed a new candidate vaccine virus to protect against those viruses.

Also, they said the newly identified highly pathogenic H7N9 viruses isolated from poultry and people are genetically and antigenically distinct from other H7N9 viruses, including recommended candidate strain, including the newly proposed one. Therefore, the group recommended a new candidate vaccine virus to protect against the highly pathogenic H7N9 strain.

The group also recommended three other candidate pandemic vaccine viruses, two against recent variant H1N1 strains and one against the recent H5N6 virus circulating in Japan and South Korea……”