Archive for April, 2017

The Los Angeles County Department of Public Health warns against consuming local deer- antler tea due to botulism risk.

Sunday, April 30th, 2017| For Immediate Release: April 28, 2017 |

For more information contact: Public Health Communications (213) 240-8144 media@ph.lacounty.gov |

| Public Health Warns Residents Not to Consume Local Deer – Antler Tea |

| LOS ANGELES – The Los Angeles County Department of Public Health (Public Health) warns against consuming local deer- antler tea due to botulism risk. Public Health has recently identified one confirmed and one suspected case of botulism occurring in adults. Preliminary investigation suggests that these cases may be associated with the consumption of a deer-antler tea product (photos attached) that was acquired during the month of March. Pending further investigation, Public Health recommends that all persons who purchased product similar to this (i.e., deer-antler tea provided in a sealed pouch similar to the attached photographs) during the month of March, immediately dispose of it.Public Health will provide more information as it becomes available.

Botulism is a rare but serious illness caused by a nerve toxin that is produced by the bacterium Clostridium. Classic symptoms of botulism include double vision, blurred vision, drooping eyelids, slurred speech, difficulty swallowing and weakness. These are all symptoms of muscle paralysis caused by the bacterial toxin. If untreated, these symptoms may progress to cause paralysis of the respiratory muscles, arms, legs, and trunk. In foodborne botulism, symptoms generally begin 18 to 36 hours after eating a contaminated food, but they can occur as early as 6 hours or as late as 10 days. The respiratory failure and paralysis that occur with severe botulism may require a patient to be on a breathing machine (ventilator) for weeks or months, plus intensive medical and nursing care. The paralysis slowly improves. People experiencing symptoms of botulism, who have recently drunk the tea, should seek immediate medical attention. For more information on botulism visit: https://www.cdc.gov/botulism/index.html Product pictures: https://t.co/e2TkWTWQpR The Los Angeles County Department of Public Health is committed to protecting and improving the health of over 10 million residents of Los Angeles County. Through a variety of programs, community partnerships and services, Public Health oversees environmental health, disease control, and community and family health. Nationally accredited by the Public Health Accreditation Board, the Los Angeles County Department of Public Health comprises nearly 4,000 employees and has an annual budget exceeding $900 million. To learn more about Los Angeles County Public Health, visit PublicHealth.LACounty.gov, and follow LA County Public Health on social media at twitter.com/LAPublicHealth, facebook.com/LAPublicHealth, and youtube.com/LAPublicHealth. ##### |

United Nations officials say at least 11 people have died from a mysterious illness in Liberia and tests have been negative for the Ebola virus.

Sunday, April 30th, 2017U.S.: There is a yellow fever vaccine shortage but there is a plan for providing safe vaccine at a limited number of clinics until the supply is replenished

Sunday, April 30th, 2017Addressing a Yellow Fever Vaccine Shortage — United States, 2016–2017

Early Release / April 28, 2017 / 66

Mark D. Gershman, MD1; Kristina M. Angelo, DO1; Julian Ritchey, MBA2; David P. Greenberg, MD2; Riyadh D. Muhammad, MD2; Gary Brunette, MD1; Martin S. Cetron, MD1; Mark J. Sotir, PhD1 (View author affiliations)

Summary

What is already known about this topic?Effective and safe yellow fever vaccines are available to prevent yellow fever disease among persons traveling to countries with yellow fever virus transmission and to comply with individual country yellow fever vaccination entry requirements; only one yellow fever vaccine (YF-VAX) is currently licensed for use in the United States. Periodic, temporary yellow fever vaccine shortages have occurred in the United States as a result of manufacturing problems, including a manufacturing complication in 2016 that resulted in the loss of a large number of U.S.-licensed yellow fever vaccine doses.

What is added by this report?To avoid a lapse in yellow fever vaccine availability to persons in the U.S. population for whom yellow fever vaccination is indicated, public health officials and private partners collaborated in pursuing an expanded access investigational new drug (eIND) application for the importation of Stamaril yellow fever vaccine into the United States. Stamaril is produced by Sanofi Pasteur, the manufacturer of the U.S.-licensed YF-VAX, and it uses the same vaccine substrain. A systematic, tiered process was developed to select clinics to participate in the eIND protocol, with the goal of reasonable accessibility to yellow fever vaccination for all U.S. residents, while assuring that clinic personnel could be adequately trained to participate in the protocol.

What are the implications for public health practice?Providers need to be aware that there is a yellow fever vaccine shortage and there is a plan for providing safe vaccine at a limited number of clinics until the supply is replenished. Domestic production of yellow fever vaccine in the United States should resume in 2018, and as the eIND protocol is implemented, CDC and Sanofi Pasteur will need to continue to collaborate throughout site recruitment and training, partner to resolve issues that arise, and maintain communication with health care providers and the general public.

Recent manufacturing problems resulted in a shortage of the only U.S.-licensed yellow fever vaccine. This shortage is expected to lead to a complete depletion of yellow fever vaccine available for the immunization of U.S. travelers by mid-2017. CDC, the Food and Drug Administration (FDA), and Sanofi Pasteur are collaborating to ensure a continuous yellow fever vaccine supply in the United States. As part of this collaboration, Sanofi Pasteur submitted an expanded access investigational new drug (eIND) application to FDA in September 2016 to allow for the importation and use of an alternative yellow fever vaccine manufactured by Sanofi Pasteur France, with safety and efficacy comparable to the U.S.-licensed vaccine; the eIND was accepted by FDA in October 2016. The implementation of this eIND protocol included developing a systematic process for selecting a limited number of clinic sites to provide the vaccine. CDC and Sanofi Pasteur will continue to communicate with the public and other stakeholders, and CDC will provide a list of locations that will be administering the replacement vaccine at a later date.

Yellow fever is an acute viral disease caused by infection with the yellow fever virus, a flavivirus primarily transmitted to humans through the bite of an infected mosquito and endemic to sub-Saharan Africa and tropical South America (1). Most infected persons are asymptomatic (1). However, the case-fatality ratio is 20%–50% among the approximately 15% of infected persons who develop severe disease (2). In recent years, multiple yellow fever outbreaks in Angola, the Democratic Republic of the Congo, and, most recently, Brazil, have underscored the ongoing and substantial global burden of this disease (3–5).

Yellow fever disease can be prevented by a live-attenuated virus vaccine that produces neutralizing antibodies in 80%–100% of vaccinees by 10 days after vaccination (2). For most travelers, only one lifetime dose is necessary (1). Vaccination is recommended for international travelers visiting areas with endemic or epidemic yellow fever virus transmission. In addition, proof-of-vaccination is required for entry into certain countries as permitted by the International Health Regulations 2015 (1,6). To provide proof of vaccination, practitioners at yellow fever vaccination clinics must validate a traveler’s vaccine record using a proof-of-vaccination stamp. CDC has regulatory authority over the designation of U.S. yellow fever vaccination clinics. For nonfederal yellow fever vaccination clinics, this authority to designate is generally delegated and overseen through a collaboration between CDC and state and territorial health departments. CDC maintains the online U.S. Yellow Fever Vaccination Center Registry of these designated clinics.

In 2015, approximately eight million U.S. residents traveled to 42 countries with endemic yellow fever virus transmission (1) (Data In, Intelligence Out [https://www.diio.net], unpublished data, 2016). Yellow fever virus can be exported by unimmunized travelers returning to countries where the virus is not endemic. Reports of yellow fever in at least 10 unimmunized returning U.S. and European travelers were recorded during 1970–2013 (1). Most recently, yellow fever virus was exported from Angola during the 2016 outbreak to three countries, with resulting local transmission in the Democratic Republic of the Congo (4). The Angola outbreak caused 965 confirmed cases from 2015 to 2017 (4). The ongoing outbreak in Brazil has resulted in 681 confirmed yellow fever cases from December 2016 through April 25, 2017 (7).

In the United States, only one yellow fever vaccine is licensed for use (YF-VAX; Sanofi Pasteur, Swiftwater, PA, 2017); approximately 500,000 doses are distributed annually to vaccinate military and civilian travelers. Approximately two thirds of these doses are distributed among approximately 4,000 civilian clinical sites (Sanofi Pasteur, unpublished data, 2017).

The current YF-VAX supply depletion began in November 2015 (8). Sanofi Pasteur was transitioning YF-VAX production from an older to a newer facility set to open in 2018, but a manufacturing complication resulted in the loss of a large number of doses. In response, Sanofi Pasteur instituted YF-VAX ordering restrictions to extend the existing supply while assessing options. In spring 2016, Sanofi Pasteur notified CDC of a probable complete depletion of YF-VAX later in the year. Sanofi Pasteur succeeded in producing additional doses of YF-VAX in late 2016; this additional supply has delayed the anticipated complete depletion until mid-2017 but remains insufficient to cover anticipated demand during the interval between permanent closure of the old facility and the 2018 opening of the new YF-VAX vaccine manufacturing facility.

Concerns about maintaining a continuous U.S. yellow fever vaccine supply, in conjunction with the large yellow fever outbreak that began in Angola, led to discussions among CDC, Sanofi Pasteur, FDA, and the U.S. Department of Defense in spring 2016. Although fractional yellow fever vaccine dosing was discussed, it was deemed a nonviable option based on limited efficacy data. Sanofi Pasteur submitted an eIND application for U.S. importation and civilian use of Stamaril, a yellow fever vaccine manufactured by Sanofi Pasteur France that is not licensed in the United States; the Department of Defense submitted its own eIND application. Stamaril uses the same vaccine substrain 17D-204 as YF-VAX, and has comparable safety and efficacy (9). Stamaril has been licensed and distributed in approximately 70 countries worldwide since 1986. Sanofi Pasteur France manufactures both multidose vials for use in global yellow fever outbreak responses and single-dose vials reserved for vaccination of international travelers living outside the United States. Sanofi Pasteur projects that importing Stamaril single-dose vials into the United States under the eIND application will not substantially affect the Stamaril supply intended for global use.

FDA accepted Sanofi Pasteur’s eIND application in October 2016. Implementation of the eIND protocol included a systematic process to select sites where Stamaril will be distributed; this process was important to manage the logistics involved in outreach and training of providers regarding adherence to the eIND protocol and FDA guidance. Sanofi Pasteur, in consultation with CDC, developed a two-tiered scheme for the selection of U.S. clinic sites to be invited to participate in the eIND protocol (Table). The primary goal was to recruit large-volume sites with adequate geographic range. Tier 1 sites were those that ordered at least 250 doses of yellow fever vaccine in 2016. Additional, smaller-volume sites were added to this tier to ensure access to Stamaril in all 50 states, the District of Columbia, and the three U.S. territories (Guam, Puerto Rico, and the U.S. Virgin Islands) with yellow fever vaccination centers. Sites were also added to guarantee vaccine access for civilian U.S. government employees needing yellow fever vaccination for official work-related travel, including critical public health response work. Tier 2 sites included multisite clinical organizations in which the aggregate number of doses ordered from their affiliated sites met the threshold of at least 250 doses in 2016. In these cases, the organization was invited to select one of its clinic sites to participate as a tier 2 site in implementing the Stamaril protocol. As of April 2017, approximately 250 clinics were targeted for inclusion. This is a sizable reduction from the estimated 4,000 civilian clinics currently providing YF-VAX.

The eIND protocol rollout began in April 2017. Sanofi Pasteur and CDC are collaborating to develop an effective communication plan. Sanofi Pasteur is recruiting and communicating with selected sites and will train personnel at participating sites by webinar in April and May 2017.

Discussion

CDC and Sanofi Pasteur have worked to assure a continuous yellow fever vaccine supply in the United States after the anticipated complete depletion of YF-VAX in mid-2017. As the eIND protocol rollout begins in April, Sanofi Pasteur will coordinate site recruitment and training, and CDC will help to resolve any problems that arise. Although the systematic site selection process for the distribution of Stamaril took into account site volume (giving preference to larger sites) and adequate geographic reach, accessibility difficulties for some international travelers might occur, because of the decrease in the number of clinics nationwide that provide yellow fever vaccination from 4,000 to 250. CDC and Sanofi Pasteur will monitor for critical gaps in vaccine access and collaborate to address any issues, including considering the possibility of recruiting additional clinics to participate as necessary.

CDC will notify state and territorial health department immunization programs about the Stamaril protocol. Information about which clinics will be eligible to receive Stamaril will be available to the public and other stakeholders, and discussed with the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices. CDC and Sanofi Pasteur continue to monitor the domestic yellow fever vaccine supply and will provide updates to health care providers and the public as new information becomes available.

Updates regarding yellow fever vaccine and the anticipated complete depletion of vaccine stock will be available on CDC’s Travelers’ Health website at https://wwwnc.cdc.gov/travel/ and Sanofi Pasteur’s website at http://www.sanofipasteur.us/vaccines/yellowfevervaccine. Once available, CDC will provide a complete list of clinics where travelers can receive Stamaril at https://wwwnc.cdc.gov/travel/yellow-fever-vaccination-clinics/search.

References

- Gershman MD, Staples JE. Yellow fever. In: Brunette GW; CDC, eds. CDC health information for international travel 2016. New York, NY: Oxford University Press; 2016.

- Staples JE, Gershman M, Fischer M. Yellow fever vaccine: recommendations of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP). MMWR Recomm Rep 2010;59(No. RR-7). PubMed

- World Health Organization. Emergency preparedness, response: yellow fever. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization; 2017. http://www.who.int/csr/don/archive/disease/yellow_fever/en/

- World Health Organization. Yellow fever outbreak Angola, Democratic Republic of the Congo and Uganda 2016–2017. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization; 2017. http://www.who.int/emergencies/yellow-fever/en/

- World Health Organization. Brazil works to control yellow fever outbreak, with PAHO/WHO support. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization; 2017. http://www2.paho.org/hq/index.php?option=com_content&view=article&id=13098%3Abrazil-control-yellow-fever-outbreak-paho-support&catid=740%3Apress-releases&Itemid=1926&lang=en

- World Health Organization. International health regulations, 2005. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization; 2008. http://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/10665/43883/1/9789241580410_eng.pdf

- Pan American Health Organization. Epidemiological update yellow fever. Washington, DC: Pan American Health Organization; 2017. http://www2.paho.org/hq/index.php?option=com_docman&task=doc_view&Itemid=270&gid=39639&lang=en

- CDC. Announcement: yellow fever vaccine shortage. Atlanta, GA: US Department of Health and Human Services, CDC; 2016. https://wwwnc.cdc.gov/travel/news-announcements/yellow-fever-vaccine-shortage-2016

- Plotkin S, Orenstein WA, Offit PA, eds. Vaccines. 6th ed. Philadelphia: Elsevier Saunders; 2013.

TABLE. Systematic tiered distribution plan for Stamaril yellow fever vaccine — United States, 2016

| Tier | Characteristic | No. of proposed sites |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Individual sites that ordered at least 250 doses in 2016 | 193 |

| Smaller sites to ensure coverage of all 50 states, DC, and U.S. territories | ||

| Sites that serve non-military U.S. government employees | ||

| 2 | Sites that are part of a multisite clinical organization whose aggregate number of orders was at least 250 doses in 2016 | 59 |

| Total | 252 | |

Abbreviation: DC = District of Columbia.

Suggested citation for this article: Gershman MD, Angelo KM, Ritchey J, et al. Addressing a Yellow Fever Vaccine Shortage — United States, 2016–2017. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. ePub: 28 April 2017. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.15585/mmwr.mm6617e2.

Serious and fatal bouts of malaria in the United States are a greater problem than has been previously reported

Sunday, April 30th, 2017The study was published Monday by The American Journal of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene.

The authors counted 22,000 patients hospitalized for malaria, about five times as many as were hospitalized, for example, for dengue fever….. Nearly 5,000 of them had serious complications like kidney failure or coma, and 182 died.

Liberia: 11 people have died and five are in hospital after contracting a mystery illness the World Health Organisation (WHO) said was linked to attendance at the funeral of a religious leader.

Saturday, April 29th, 2017

- The symptoms include fever, vomiting and diarrhea

- Hospital staff are wearing protective equipment

- Contacts of the sick are being traced in the community to see if they have fallen ill

- WHO, U.S. Centers for Disease Control and other partners are providing technical and logistical support to the rapid response team that has been activated at district and county levels

The world’s first vaccine against malaria will be introduced in three countries – Ghana, Kenya and Malawi – starting in 2018.

Monday, April 24th, 2017“….Despite huge progress, there are still 212 million new cases of malaria each year and 429,000 deaths…..”

Chagas Disease: Approximately 300,000 people are living with this disease in the United States.

Sunday, April 23rd, 2017

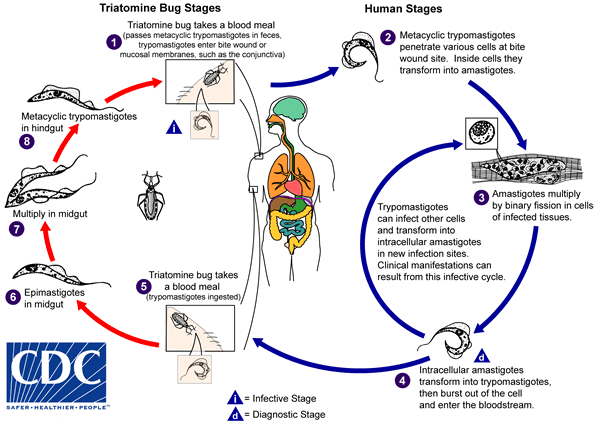

An infected triatomine insect vector (or “kissing” bug) takes a blood meal and releases trypomastigotes in its feces near the site of the bite wound. Trypomastigotes enter the host through the wound or through intact mucosal membranes, such as the conjunctiva  . Common triatomine vector species for trypanosomiasis belong to the genera Triatoma, Rhodnius, and Panstrongylus. Inside the host, the trypomastigotes invade cells near the site of inoculation, where they differentiate into intracellular amastigotes

. Common triatomine vector species for trypanosomiasis belong to the genera Triatoma, Rhodnius, and Panstrongylus. Inside the host, the trypomastigotes invade cells near the site of inoculation, where they differentiate into intracellular amastigotes  . The amastigotes multiply by binary fission

. The amastigotes multiply by binary fission  and differentiate into trypomastigotes, and then are released into the circulation as bloodstream trypomastigotes

and differentiate into trypomastigotes, and then are released into the circulation as bloodstream trypomastigotes  . Trypomastigotes infect cells from a variety of tissues and transform into intracellular amastigotes in new infection sites. Clinical manifestations can result from this infective cycle. The bloodstream trypomastigotes do not replicate (different from the African trypanosomes). Replication resumes only when the parasites enter another cell or are ingested by another vector. The “kissing” bug becomes infected by feeding on human or animal blood that contains circulating parasites

. Trypomastigotes infect cells from a variety of tissues and transform into intracellular amastigotes in new infection sites. Clinical manifestations can result from this infective cycle. The bloodstream trypomastigotes do not replicate (different from the African trypanosomes). Replication resumes only when the parasites enter another cell or are ingested by another vector. The “kissing” bug becomes infected by feeding on human or animal blood that contains circulating parasites  . The ingested trypomastigotes transform into epimastigotes in the vector’s midgut

. The ingested trypomastigotes transform into epimastigotes in the vector’s midgut  . The parasites multiply and differentiate in the midgut

. The parasites multiply and differentiate in the midgut  and differentiate into infective metacyclic trypomastigotes in the hindgut

and differentiate into infective metacyclic trypomastigotes in the hindgut  .

.

Trypanosoma cruzi can also be transmitted through blood transfusions, organ transplantation, transplacentally, and in laboratory accidents.

Chagas disease is caused by the parasite Trypanosoma cruzi, which is transmitted to animals and people by insect vectors that are found only in the Americas (mainly, in rural areas of Latin America where poverty is widespread). Chagas disease (T. cruzi infection) is also referred to as American trypanosomiasis.

It is estimated that as many as 8 million people in Mexico, Central America, and South America have Chagas disease, most of whom do not know they are infected. If untreated, infection is lifelong and can be life threatening.

The impact of Chagas disease is not limited to the rural areas in Latin America in which vectorborne transmission occurs. Large-scale population movements from rural to urban areas of Latin America and to other regions of the world have increased the geographic distribution and changed the epidemiology of Chagas disease. In the United States and in other regions where Chagas disease is now found but is not endemic, control strategies should focus on preventing transmission from blood transfusion, organ transplantation, and mother-to-baby (congenital transmission).

How do people get Chagas disease?

People can become infected in various ways. In Chagas disease-endemic areas, the main way is through vectorborne transmission. The insect vectors are called triatomine bugs. These blood-sucking bugs get infected by biting an infected animal or person. Once infected, the bugs pass T. cruzi parasites in their feces. The bugs are found in houses made from materials such as mud, adobe, straw, and palm thatch. During the day, the bugs hide in crevices in the walls and roofs. During the night, when the inhabitants are sleeping, the bugs emerge. Because they tend to feed on people’s faces, triatomine bugs are also known as “kissing bugs. ” After they bite and ingest blood, they defecate on the person. The person can become infected if T. cruzi parasites in the bug feces enter the body through mucous membranes or breaks in the skin. The unsuspecting, sleeping person may accidentally scratch or rub the feces into the bite wound, eyes, or mouth.

People also can become infected through:

- congenital transmission (from a pregnant woman to her baby);

- blood transfusion;

- organ transplantation;

- consumption of uncooked food contaminated with feces from infected bugs; and

- accidental laboratory exposure.

It is generally considered safe to breastfeed even if the mother has Chagas disease. However, if the mother has cracked nipples or blood in the breast milk, she should pump and discard the milk until the nipples heal and the bleeding resolves.

Chagas disease is not transmitted from person-to-person like a cold or the flu or through casual contact with infected people or animals.

If I have Chagas disease, should my family members be tested for the infection?

Possibly. They should be tested if they:

- could have become infected the same way that you did, for example, by vectorborne transmission in Latin America;

- received blood or organs that you donated after you already were infected;

- are your children and were born after you were infected; or if

- there are other reasons to think that they might have Chagas disease.

In what parts of the world is Chagas disease found?

People who have Chagas disease can be found anywhere in the world. However, vectorborne transmission is confined to the Americas, principally rural areas in parts of Mexico, Central America, and South America. In some regions of Latin America, vector-control programs have succeeded in stopping this type of disease spread. Vectorborne transmission does not occur in the Caribbean (for example, in Puerto Rico or Cuba). Rare vectorborne cases of Chagas disease have been noted in the southern United States.

What are the signs and symptoms of Chagas disease?

Much of the clinical information about Chagas disease comes from experience with people who became infected as children through vectorborne transmission. The severity and course of infection might be different in people infected at other times of life, in other ways, or with different strains of the T. cruzi parasite.

There are two phases of Chagas disease: the acute phase and the chronic phase. Both phases can be symptom free or life threatening.

The acute phase lasts for the first few weeks or months of infection. It usually occurs unnoticed because it is symptom free or exhibits only mild symptoms and signs that are not unique to Chagas disease. The symptoms noted by the patient can include fever, fatigue, body aches, headache, rash, loss of appetite, diarrhea, and vomiting. The signs on physical examination can include mild enlargement of the liver or spleen, swollen glands, and local swelling (a chagoma) where the parasite entered the body. The most recognized marker of acute Chagas disease is called Romaña’s sign, which includes swelling of the eyelids on the side of the face near the bite wound or where the bug feces were deposited or accidentally rubbed into the eye. Even if symptoms develop during the acute phase, they usually fade away on their own, within a few weeks or months. Although the symptoms resolve, if untreated the infection persists. Rarely, young children (<5%) die from severe inflammation/infection of the heart muscle (myocarditis) or brain (meningoencephalitis). The acute phase also can be severe in people with weakened immune systems.

During the chronic phase, the infection may remain silent for decades or even for life. However, some people develop:

- cardiac complications, which can include an enlarged heart (cardiomyopathy), heart failure, altered heart rate or rhythm, and cardiac arrest (sudden death); and/or

- intestinal complications, which can include an enlarged esophagus (megaesophagus) or colon (megacolon) and can lead to difficulties with eating or with passing stool.

The average life-time risk of developing one or more of these complications is about 30%.

What should I do if I think I have Chagas disease?

You should discuss your concerns with your health care provider, who will examine you and ask you questions (for example, about your health and where you have lived). Chagas disease is diagnosed by blood tests. If you are found to have Chagas disease, you should have a heart tracing test (electrocardiogram), even if you feel fine. You might be referred to a specialist for more tests and for treatment.

What if I’ve been diagnosed with Chagas disease but have a normal EKG?

If you have been diagnosed with Chagas disease, your doctor may perform an electrocardiogram (EKG or ECG) to check for any problems with the electrical activity of your heart. Even if this test is normal, you still may need to be given antiparasitic medication used to treat Chagas disease. Your physician may wish to review CDC’s recommendations for evaluation and treatment for more information.

How is Chagas disease treated?

There are two approaches to therapy, both of which can be life saving:

- antiparasitic treatment, to kill the parasite; and

- symptomatic treatment, to manage the symptoms and signs of infection.

Antiparasitic treatment is most effective early in the course of infection but is not limited to cases in the acute phase. In the United States, this type of treatment is available through CDC. Your health care provider can talk with CDC staff about whether and how you should be treated. Most people do not need to be hospitalized during treatment.

Symptomatic treatment may help people who have cardiac or intestinal problems from Chagas disease. For example, pacemakers and medications for irregular heartbeats may be life saving for some patients with chronic cardiac disease.

I plan to travel to a rural area of Latin America that might have Chagas disease. How can I prevent infection?

No drugs or vaccines for preventing infection are currently available. Travelers who sleep indoors, in well-constructed facilities (for example, air-conditioned or screened hotel rooms), are at low risk for exposure to infected triatomine bugs, which infest poor-quality dwellings and are most active at night. Preventive measures include spraying infested dwellings with residual-action insecticides, using bed nets treated with long-lasting insecticides, wearing protective clothing, and applying insect repellent to exposed skin. In addition, travelers should be aware of other possible routes of transmission, including bloodborne and foodborne.

WHO’s Global Hepatitis Report, 2017: Since 2000, deaths from viral hepatitis have increased by 22%.

Sunday, April 23rd, 2017