Bubonic Plague in History

September 27th, 2017Model-based analysis of an outbreak of bubonic plague in Cairo in 1801

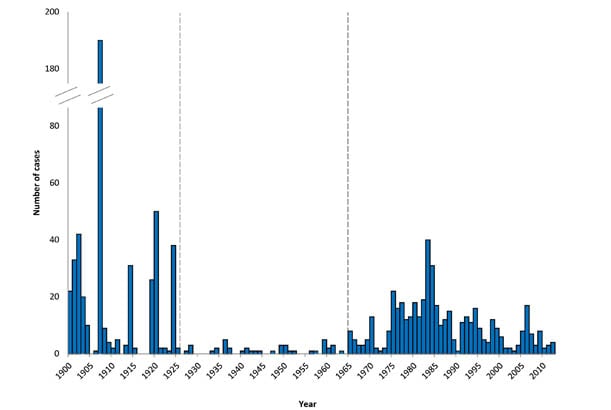

“….Bubonic plague is arguably the most devastating infectious disease that mankind has ever been confronted with. Its causative agent, Yersinia pestis, has recently been detected in several human remains dated from the third millennium BCE but at that time lacked the ability to cause epidemics of bubonic plague transmitted by ectoparasites [1,2]. Genetic adaptation to the flea-borne pathogenic lifestyle is estimated to have happened shortly before the beginning of the first millennium BCE [1,3,4], which coincides with some of the first historical descriptions of epidemics that have been putatively attributed to bubonic plague. Ancient historical descriptions are, however, typically insufficient to reach a clear verdict of plague. For example, the disease that struck the Philistines in the eleventh century BCE has been proposed to be the earliest known outbreak of bubonic plague, but could in fact have been caused by dysentery or tularaemia [5,6]. Likewise, the outbreak that ravaged Athens in 430 BCE could have been a number of infectious diseases other than plague, such as Ebola [7,8]. Although there would certainly have been earlier cases at least sporadically, the first human deaths that have been conclusively attributed to Y. pestis using DNA evidence occurred in the sixth century CE, during the so-called plague of Justinian [9,10]. This epidemic was first reported by the contemporary historian Procopius in Egypt in 541 CE, and it would have spread rapidly on ships carrying grain to Constantinople and throughout the Byzantine empire [11]. The first plague pandemic followed, which ravaged Mediterranean and European regions through several waves over the next 200 years [12]. The second plague pandemic started in 1347 with the so-called Black Death epidemic. Once again, DNA evidence has been used to incriminate Y. pestis as the infectious agent [13,14]. The epidemic originated in Central Asia before spreading throughout Europe via trade routes [15]. In Western Europe, the second pandemic lasted until the end of the seventeenth century, with the Marseilles plague of 1720 being an exceptionally late outbreak [16]. For example, in England, the last major outbreak took place in 1665 in London and a few secondary locations [17,18]. Finally, a third pandemic started around 1855 which ravaged China and India for almost a century, and during which the causative bacteria Y. pestis was discovered as well as its flea-borne mode of transmission [19].

Phylogenetic evidence indicates that the third pandemic was caused by a direct descendant from the lineage that had caused the second pandemic [10,15]. Between the end of the second and the beginning of the third pandemic, this lineage would have been restricted to the Middle East [10]. Outbreaks of bubonic plague were indeed regularly reported during the interpandemic period, for example, in Iraq [20], in Syria [21] and in Egypt [21–25]. A comprehensive survey of historical reports of epidemics shows that throughout the eighteenth century and the first half of the nineteenth century, plague was documented in Asia Minor in approximately 85% of years, in Lower Egypt in approximately 30% of years and in Syria in approximately 20% of years [26]. This recurrence of plague in the Middle East at a time when Europe was free of it significantly contributed to the weakening of the Ottoman Empire [22]. Several Western visitors were surprised by the lack of measures taken by the local population to try and protect itself from the disease [25,26]. Very high plague death tolls were recorded by contemporary writers, but many of these were exaggerated and the aetiology is often unclear [25,27]. Thus, although it is beyond doubt that the Middle East was frequently hit by plague between 1700 and 1850, little is known about this important connecting link between the second and third pandemics, and there are virtually no reliable data available for formal epidemiological investigation.

A notable exception concerns the short period from 1798 to 1801 during which a French revolutionary expedition into Ottoman Egypt was led by the future emperor Napoleon Bonaparte. Many French scientists accompanied this expedition, who studied many aspects of the Egyptian country they visited, such as its topography, climate, history, demography and languages. The expedition included a large number of medical officers headed by René Desgenettes who together collected a wealth of medical observations about the health of the Egyptian population [28,29]. Upon his return, Desgenettes reported his findings in a book entitled ‘Histoire médicale de l’armée d’Orient’ which includes a table of the daily number of deaths recorded among men, women and children living in Cairo [30]. This daily mortality statistical table covers an epidemic of plague that took place in early 1801 and which is briefly mentioned in Desgenettes’ book [30] as well as a few monographs written by other medical officers returning from the French expedition [31–33] and secondary sources [34–36]. These data present a unique opportunity to dissect how an outbreak of bubonic plague unfolded in interpandemic Egypt….”