Archive for February, 2018

M 6.4 – 22km NNE of Hualian, Taiwan

Tuesday, February 6th, 2018

Tectonic Summary

The February 6, 2018, M 6.4 earthquake north-northeast of Hualien, Taiwan, occurred as the result of oblique strike-slip faulting at shallow depth, near the plate boundary between the Philippine Sea and Eurasia plates at the northeast coast of Taiwan. Preliminary focal mechanism solutions for the earthquake indicate rupture occurred on a steep fault striking either east-southeast (right-lateral), or south-southwest (left-lateral). At the location of this earthquake, the Philippine Sea plate converges with the Eurasia plate at a velocity of approximately 75 mm/yr towards the northwest. The location, depth and mechanism of the February 6, 2018 earthquake are consistent with its occurrence on, or along a fault in close proximity and relation to, the complex plate boundary in this region.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=YibvTBty7jo

Taiwan lies in a region of complex tectonics near the intersection of three major tectonic plates – the Philippine Sea plate to the east and southeast, the Eurasia plate to the north and west, and the Sunda plate to the southwest. The location of the February 6, 2018 earthquake lies near the end of the Ryukyu subduction zone, which marks the plate boundary between the Philippine Sea and Eurasia plates in this region. The plate boundary in Taiwan itself is characterized by a zone of arc-continent collision; whereby the northern end of the Luzon (Philippines) island arc is colliding with the buoyant crust of the Eurasia continental margin offshore China. Along Taiwan’s west coast, and continuing south, this collision zone transitions into the eastward-oriented Manila subduction zone.

The February 6, 2018 earthquake is the largest in a sequence of events in the same region over the past several days. Beginning with a M 4.8 earthquake on February 3, 2018, there have been 19 earthquakes of M 4.5 and larger (as of February 6, 2018, 20:00 UTC). A M 6.1 earthquake occurred as a result of thrust-type faulting on February 4, 2018, just a few kilometers southeast of this M 6.4 earthquake on February 6th.

Because of its plate boundary location, Taiwan commonly experiences moderate-to-large earthquakes. The region within 250 km of today’s earthquake has hosted 184 other M 6+ earthquakes over the preceding century; 25 of these were M 7+. These include a M 7.1 earthquake in September 1922, 25 km to the northeast of the February 6, 2018 earthquake, and a M 7.1 event in March 2002, 55 km to the northeast. The 2002 event resulted in at least 5 fatalities, over 200 injuries, 3 collapsed buildings and the destruction of over 100 houses in the T’ai-pei area. The September 1999, M 7.7 Chi Chi earthquake occurred in central Taiwan, 81 km to the southwest of today’s earthquake. That earthquake resulted in at least 2,297 fatalities, and caused damage estimated at $14 billion.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=7CQrzj0Ptuc

After Maria, FEMA awarded Tiffany Brown, an Atlanta entrepreneur with no experience in large-scale disaster relief and at least five canceled government contracts in her past, $156 million for 30 million meals for Puerto Ricans. 50,000 were delivered.

Tuesday, February 6th, 2018“…..In November, The Associated Press found that after Hurricane Maria, FEMA awarded more than $30 million in contracts for emergency tarps and plastic sheeting to a company that never delivered the needed supplies…..”

WHO: Global Violence and Injury

Tuesday, February 6th, 2018Violence

Globally, some 470 000 homicides occur each year and millions of people suffer violence-related injuries. Beyond death and injury, exposure to violence can increase the risk of smoking, alcohol and drug abuse; mental illness and suicidality; chronic diseases like heart disease, diabetes and cancer; infectious diseases such as HIV, and social problems such as crime and further violence.

Road traffic injuries

Over 3 400 people die on the world’s roads every day and tens of millions of people are injured or disabled every year. Children, pedestrians, cyclists and older people are among the most vulnerable of road users.

Drowning

Drowning is a leading killer. The latest WHO Global Health Estimates indicate that almost 360 000 people lost their lives to drowning in 2015. Nearly 60% of these deaths occur among those aged under 30 years, and drowning is the third leading cause of death worldwide for children aged 5-14 years. Over 90% of drowning deaths occur in low- and middle-income countries.

Burns

A burn is an injury to the skin or other organic tissue primarily caused by heat but can also be due to radiation, radioactivity, electricity, friction or contact with chemicals. Skin injuries due to ultraviolet radiation, radioactivity, electricity or chemicals, as well as respiratory damage resulting from smoke inhalation, are also considered to be burns.

Globally, burns are a serious public health problem. An estimated 180 000 deaths occur each year from fires alone, with more deaths from scalds, electrical burns, and other forms of burns, for which global data are not available.

According to the 2015 Global Health Estimates, 95% of fatal fire-related burns occur in low- and middle-income countries. In addition to those who die, millions more are left with lifelong disabilities and disfigurements, often with resulting stigma and rejection.

The suffering caused by burns is even more tragic as burns are so eminently preventable.

Falls

A fall is an event which results in a person coming to rest inadvertently on the ground or floor or other lower level. Within the WHO database fall-related deaths and non-fatal injuries exclude those due to assault and intentional self-harm. Falls from animals, burning buildings and transport vehicles, and falls into fire, water and machinery are also excluded.

Globally, an estimated 391 000 people died due to falls in 2002, making it the 2nd leading cause of unintentional injury death globally after road traffic injuries. A quarter of all fatal falls occurred in the high-income countries. Europe and the Western Pacific region combined account for nearly 60 % of the total number of fall-related deaths worldwide

Males in the low- and middle-income countries of Europe have by far the highest fall-related mortality rates worldwide.

In all regions of the world, adults over the age of 70 years, particularly females, have significantly higher fall-related mortality rates than younger people. However, children account for the largest morbidity- almost 50% of the total number of DALYs lost globally to falls occur in children under 15 years of age.

Urban water demand will increase by 80% by 2050

Monday, February 5th, 2018Water competition between cities and agriculture driven by climate change and urban growth

Martina Flörke, Christof Schneider & Robert I. McDonald

Nature Sustainability 1, 51–58 (2018)

doi:10.1038/s41893-017-0006-8

“….We project an urban surface-water deficit of 1,386–6,764 million m³. More than 27% of cities studied, containing 233 million people, will have water demands that exceed surface-water availability. An additional 19% of cities, which are dependent on surface-water transfers, have a high potential for conflict between the urban and agricultural sectors, since both sectors cannot obtain their estimated future water demands. ….”

Drug Shortages Roundtable: Minimizing Impact on Patient Care

Sunday, February 4th, 2018Held November 6, 2017, at ASHP Headquarters, Bethesda, MD

Meeting Attendees: American Hospital Association American Medical Association American Society of Clinical Oncology American Society of Anesthesiologists American Society of Health-System Pharmacists American Society of Parenteral and Enteral Nutrition Institute for Safe Medication Practices Pew Charitable Trusts Society of Critical Care Medicine University of Utah Drug Information Services

Public Sector Meeting Attendees: Food and Drug Administration Department of Health and Human Services Office of the Assistant Secretary for Preparedness and Response

Background

Drug shortages are an ongoing public health concern in the United States. Although the numbers of newly reported drug shortages (170) are much lower than at the height of the shortage crisis in 2012 (305), clinicians continue to experience supply challenges of certain medications. These medications are typically injectable products that are off-patent and have few suppliers. Causes of these shortages do not appear to have changed: Drug shortages are largely the result of quality problems during the manufacturing process, which give rise to a halt in production in order to address the problem. In the case of a product with few competitors, this disruption in production cannot be absorbed by other companies, and demand outpaces supply, resulting in a shortage. In the case of a sole-source manufacturer, no alternatives for production exist, and clinicians must either struggle to obtain a supply of the drug, compound a drug when possible, or recommend an alternative therapy if one exists.

Since the height of the shortage crisis, legislation enacted in 2012 requires that drug manufacturers notify the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) “of any change in production that is reasonably likely to lead to reduction in supply” of a covered drug in the U.S. This advanced warning requirement has played a significant role in reducing the number of drug shortages, but it has not solved the problem.

Drug Shortages Roundtable: Minimizing Impact on Patient Care November 6, 2017 Page 2

A further complication occurred in late September 2017, as a major hurricane struck Puerto Rico, which houses significant drug manufacturing infrastructure. The result thus far has been a shortage of small-volume parenteral solution (SVP) products due to production and supply problems on the island. SVP products include saline bags, which are the foundation of basic intravenous (IV) compounding for hundreds of drugs that need further dilution, such as antibiotics, chemotherapy drugs, and electrolytes. They are also frequently used to start IV lines or administer blood.

Overview

In November 2017, ASHP (American Society of Health-System Pharmacists) convened a meeting of healthcare professional organizations — the American Hospital Association (AHA), the FDA, and the Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) office of the Assistant Secretary for Preparedness and Response (ASPR) — to review and identify new opportunities to address the ongoing supply chain and patient-care challenges associated with drug product shortages. The meeting served as an opportunity to examine how the FDA Safety and Innovation Act (FDASIA), enacted in 2012, has impacted shortages, and to address whether there is a need to build on the law with new recommendations. Held at ASHP headquarters, the meeting featured attendees that represented not only a large part of the clinician community, but also the AHA, the Pew Charitable Trusts, and the University of Utah Drug Information Services. At the meeting, representatives from the American Society of Anesthesiologists, the American Society of Clinical Oncology, the American Medical Association, the American Society of Parenteral and Enteral Nutrition, the Institute for Safe Medication Practices, and the Society of Critical Care Medicine discussed the ongoing challenges of drug shortages and their impact on patient care. In addition, the FDA and the ASPR’s Office of Emergency Management were in attendance.

FDA

The meeting began with a presentation by Captain Valerie Jensen of the FDA Drug Shortage program. Captain Jensen reported that the notification requirement enacted as part of FDASIA is generally being followed and that most companies do report to the agency when there is a production problem. This reporting enables the FDA to work with other manufacturers behind the scenes to ramp up production, to allow for expedited review of another company’s abbreviated new drug application (ANDA), or, in extreme cases, to begin the process of controlled importation of a drug to meet demand. Manufacturers are required to notify the FDA six months in advance or, if that is not possible, as soon as practicable thereafter but in no case later than five business days after the discontinuance or interruption in manufacturing. If a company fails to comply with the reporting requirement, the FDA sends a letter notifying the company that it is not in compliance with the law. Captain Jensen also noted that the requirement to notify the FDA does not obligate the manufacturer to disclose the problem that led to the interruption, its expected duration, or an estimated time frame for resolving the problem.

Drug Shortages Roundtable: Minimizing Impact on Patient Care November 6, 2017 Page 3

In recent years, the FDA has been working closely with international regulatory agencies to engage in controlled importation of drugs in short supply. This collaboration has not only resulted in more reliance on foreign inspection history, but has also bolstered agency relationships with foreign sources. The FDA noted that as other countries also experience shortages, controlled importation is not a longterm solution.

In the FDA’s presentation, it was also noted that while the FDA can require advance notification of supply disruptions and product discontinuations, the agency cannot require a company to manufacture a drug, no matter how critical or life-sustaining it is. The FDA believes that better reporting in terms of listing the actual production problems, as well as estimated timelines for resolution, would help. In addition, the FDA noted that while it encourages companies to develop drug shortage contingency plans, more could be done to incentivize companies to develop such plans, including providing for manufacturing redundancy to have a backup system in place should a production line be brought out of service.

University of Utah Drug Information Service

Erin Fox, PharmD., of the University of Utah Drug Information Service also presented on drug shortages. Dr. Fox noted that the current shortage trend includes IV antibiotics, IV fluids (including saline), and other widely used products such as emergency syringes, sodium bicarbonate, carpujects, amino acids, and parenteral nutrition (PN) products. One improvement is the significant decline over the past five years in the numbers of shortages of chemotherapy drugs. Dr. Fox emphasized, however, that current shortages are impacting all areas of the hospital, from specialties to acute care centers.

Dr. Fox also cited a Government Accountability Office report from 2016 that identified the key factors in drug shortages, including few suppliers, poor manufacturing processes, and typically low-margin generic products.

Many of the drugs in short supply are basic products needed to care for patients in hospitals, clinics and other patient care settings. Shortages of these types of medications are having a significant effect on patient care, as options to address the problem are limited or risky. Further, while increasing automation in hospitals has created efficiencies, these systems are often designed to use a certain product. When an alternative product must be used, due to a shortage, it creates a burdensome workload to make changes. Dr. Fox cited the use of smart pumps and the labor-intensive process for changing a drug in the electronic health record (EHR). Further exacerbating the problem are the FDA requirements that prohibit the storage of drugs in syringes, yet syringe pumps are approved for use.

Following the presentations, Allen Vaida of the Institute for Safe Medication Practices (ISMP) described the results of an August 2017 drug shortage survey. The ISMP survey revealed that 55% of respondents indicated experiencing a shortage of 21 or more drugs within the last six months. Roughly 27%

Drug Shortages Roundtable: Minimizing Impact on Patient Care November 6, 2017 Page 4

reported weekly shortages, and 66% reported daily shortages. According to the survey, 90% of respondents reported increasing inventory, hoarding, and rationing supplies of drugs in shortage. In addition, survey participants commented that other strategies being employed include re-deploying medications used for crash carts, reusing vials, extending hang times for IVs, and transitioning infusion devices to push IVs prepared and administered by nurses. Survey respondents also described delays resulting from labor-intensive re-entry of new drugs into computerized provider order entry (CPOE) systems.

New Compounding Outsourcer Category under Section 503B of the Drug Quality and Security Act

In 2013, legislation was enacted in the wake of the New England Compounding Center tragedy to provide more regulatory oversight of compounding. The law created a new category of compounder, called an outsourcing facility, which is regulated under Section 503B of the Food, Drug and Cosmetics Act. The new category allows firms that compound drugs without a prescription to be licensed and inspected by the FDA rather than by the state board of pharmacy. These firms are not classified as pharmacies but more closely resemble drug manufacturers. Given this new category, and the regulatory exception that allows compounding of drugs in short supply, the question was raised as to whether these 503B outsourcers could fill the gap and produce drugs in short supply.

The group discussed the challenges associated with the 503B market as a solution to the drug shortage problem. According to the group, the largest hurdle is the unpredictability of drug shortages. It is often not known ahead of time if a drug will be in short supply. Typically, it takes five to six weeks for 503B firms to ramp up production of a drug, and they can do so only when a product appears on the FDA shortage list. This makes the marketplace uncertain for products compounded by outsourcing facilities, because they cannot predict which products will be in short supply or how long the shortage will last. In addition, many 503B outsourcers are not equipped to produce drugs directly from active pharmaceutical ingredients (APIs).

The group noted that, with respect to the situation in Puerto Rico, 503B firms simply cannot make SVP solutions because the majority of empty bags needed to do so are manufactured in Puerto Rico. Additionally, extremely large volumes of these products are needed. For example, a 500-bed inpatient hospital can easily require 20,000, 100 mL bags of saline for a single month. In addition, many 503B outsourcing facilities have been issued an FDA Form 483, which is FDA’s inspection form used when a facility is reviewed. These are posted online by FDA, but no additional information is posted to denote whether or not the facility has fixed the findings outlined in the 483. This creates uncertainty for hospitals attempting to select a facility and prevents the 503B outsourcing facilities from playing a larger role in mitigating the impact of drug shortages.

Drug Shortages Roundtable: Minimizing Impact on Patient Care November 6, 2017 Page 5

Input from ASPR, Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) Dr. Laura Wolf, the Branch Chief of Critical Infrastructure Protection at the Office of the Assistant Secretary for Preparedness and Response (ASPR), Office of Emergency Management, described ASPR’s efforts to coordinate with other public and private sector organizations involved in disaster response, including the Department of Homeland Security (DHS). Dr. Wolf identified DHS’s list of critical infrastructure, which includes public health and healthcare, and noted that DHS may re-examine criteria for determining vulnerability of that infrastructure.

In addition, the suggestion was made that manufacturing locations be evaluated and considered as criteria for determining risk. The situation in Puerto Rico underscores the need to track critical drug products and their manufacturers, as well as evaluate the location of manufacturing. Dr. Wolf agreed that more timely information is needed in a disaster response regarding where drugs and other medical products are being produced and that currently such information is considered proprietary. She stated that ASPR would like to work more closely with major manufacturers to explain the benefits of sharing such information with HHS. That is, if manufacturers are identified as critical infrastructure, it would be safe to share this otherwise proprietary information with HHS/DHS because, by law, this information-sharing is protected from public disclosure and used only in the context of preparedness planning and response. In terms of benefits to drug manufacturers, Dr. Wolf noted that HHS works with DHS and can provide analytical tools to help manufacturers prepare for disasters and identify their dependencies (e.g., power and water) and how they can become more resilient.

Dr. Wolf also noted that HHS is working with other federal partners to help identify additional authorities who can support FDA’s drug shortage program efforts to prepare, prevent, and respond to shortages. She stated that HHS is convening discussions with the Department of Defense and the Veterans Administration, which purchase large amounts of drugs and other medical products. HHS is exploring whether such government customers can make changes in contracts to help support the resilience of these manufacturers.

Among other initiatives, due to predictions of an early and severe influenza season, the lack of saline is a national security challenge. HHS is exploring what potential authority it has and what assistance it can provide through its various programs within ASPR, HHS, and other government agencies. Finally, ASPR is exploring whether it can predict future shortages, determine where they might occur, and find ways to support manufacturers in implementing plans such as ensuring that drug shortage contingency plans and enhanced redundancies in production/distribution are in place.

The group also discussed the need to develop a list of critical medications, perhaps the top 10 or 20 most commonly used, life-sustaining therapies deemed most critical to patient care. This list of medications would be deemed a priority for the protection of public health, and special consideration could be given to maintaining the supply of these medications. The group noted the difficulty with this

Drug Shortages Roundtable: Minimizing Impact on Patient Care November 6, 2017 Page 6

approach, as many products can be considered critical when in short supply. Further, participants noted the challenge of developing a list of drugs from the 2010 drug shortages summit, a topic that was discussed during that meeting and later abandoned. One key difference between 2010 and 2017 is that the shortage of SVP products has generated significantly more panic among caregivers than other shortages. It appears evident that the magnitude and impact of this shortage is much more widespread than previous shortages. While consensus was not reached on developing a critical drug list, the group agreed that further discussion of this question may be warranted.

Key Questions 1. What has worked in the last four years, and what has changed? Early notification of discontinuances and interruptions has helped FDA mitigate the impact of drug shortages through behind-the-scenes work with manufacturers, some of them foreign sources, to expedite approval of new suppliers, increase production of alternative products, and arrange for importation of supplies during an impending shortage. The FDA reported that while most manufacturers notify the agency in advance, as required, a few companies have failed to meet the reporting requirements. The FDA suggested the need for additional manufacturer education regarding their responsibility to report.

In addition, many stakeholders question the accuracy of manufacturer reporting. There is a desire among the group to supplement existing law by requiring reporting of the actual manufacturing problem to the FDA, including an estimated timeline for resolution. The FDA reported that if a manufacturer is going to bring production down for a significant amount of time, such additional information would be useful to the agency as it examines controlled importation or expedited review of another company. Currently, this is not required under FDASIA. 2. Are there new trends with respect to shortages, new causes, or factors that have emerged? For the most part, drug shortages are still caused by manufacturing quality problems and primarily impact generic, sterile injectable products. But there have been a few differences in types of drug shortages from past years. First, the numbers of shortages of oncology products has declined significantly. The remaining drug classes experiencing shortages, including antibiotics, amino acids, and TPN products, are nothing new. The more troubling shortages, however, are occurring with the most widely used products, for which a large amount is needed, such as saline. Such shortages impact nearly every area of hospitals and acute care centers.

While most shortages involve sterile injectable products, it was noted that a few oral products also appear on the shortage list. These shortages are less likely to be a result of manufacturing quality issues and more likely to be based on marketplace factors, such as competitors withdrawing from the market. A related issue is how business decisions, such as mergers, impact drug shortages. The

Drug Shortages Roundtable: Minimizing Impact on Patient Care November 6, 2017 Page 7

purchase of Hospira by Pfizer, for example, brings into question whether the new parent company is continuing to invest in new production capacity and facilities. The group suggested that the Federal Trade Commission should consider an additional factor in its evaluations of buyouts or mergers, specifically the potential impact such an action may have on the supply of drugs. 3. What recommendations, including policy options, may be needed? Throughout the day, the group discussed potential policy options. Listed below, these options range from improving the requirements in Title X of FDASIA, to looking at new strategies and incentives to bolster the market, to providing some type of contingency planning. It is important to note that the recommendations were the result of discussion among the non-government groups and cannot be attributed to either HHS or the FDA.

Recommendations 1. Manufacturers should provide the FDA with more information on the causes of the shortages and their expected durations. Current law requires manufacturers to notify FDA when there is a discontinuance or interruption in manufacturing. However, manufacturers are not required to disclose the problem causing the interruption or to provide a timeline for resolution. This lack of information hinders the ability of healthcare providers to plan for shortages. Title X should be strengthened to require these notifications to include disclosure of the problem causing the interruption and an expected timeline to address the shortage.

2. Establish best practices for high-alert drugs. Best practices should be established for utilizing certain widely used and critical drugs. This will not only be helpful in the event of a shortage and, if widely applied, also will reduce waste throughout the healthcare system, thus helping to prevent shortage situations. Focus should specifically be placed on limiting IV fluid waste. Once best practices are established, a multidisciplinary educational component will need to be implemented to ensure that all medical professionals are trained and educated in these best practices for limiting IV fluid waste. 3. FDA should require manufacturers to establish contingency plans and/or redundancies. Manufacturers cannot always predict when a shortage will take place. Such shortages have negative impacts on patient safety and on access to care. Therefore, it is recommended that manufacturers establish contingency plans for a drug shortage, specifically when there are fewer than three manufacturers producing a drug.

Drug Shortages Roundtable: Minimizing Impact on Patient Care November 6, 2017 Page 8

4. FDA should establish incentives to encourage manufacturers to produce drugs in shortage. When a drug is in shortage, it is often difficult to find a manufacturer willing to increase or begin production of the drug. Therefore, the FDA should explore incentive options to encourage other manufacturers to begin producing drugs that are in shortage. Incentives should also be considered for outsourcing facilities that compound drugs, as provided under section 503B of the Food, Drug and Cosmetics Act. 5. FDA should provide more information on the quality of outsourcing facilities’ compounding. Although outsourcing facilities registered with the FDA under section 503B are able to compound drugs that are in shortage, it is difficult for pharmacies to evaluate the quality of a 503B facility. This is especially true for an outsourcing facility that has been issued an FDA Form 483, indicating that the company has a problem with quality. The recommendation is for FDA to include not only more disclosure on its website regarding why the 483 was issued, but also the timely removal of the 483 when the issue has been resolved. 6. Reconsider the purchasing process of saline. As saline is used more widely than most drugs, the group discussed having saline unbundled from the purchasing of other supplies. Additionally, the group proposes that an authoritative body such as the Federal Trade Commission look into the purchasing process to determine if it is stifling competition. 7. Manufacturers need to be more transparent. Title X of FDASIA could be strengthened to require more transparency. The recommendation is for manufacturers to disclose to the FDA the location of production, including situations where a contract manufacturer is used. Further, there may be situations, such as the hurricane in Puerto Rico, where FDA could release the names of products produced at certain locations to allow clinicians to make patient care plans in advance. In these situations, allocated purchasing could also be employed as a means to prevent hoarding. 8. Examine drug shortages as a national security initiative. When a drug is in shortage, it impacts all forms of medical care, from public and private hospitals to the U.S. military and VA medical centers. The group recommends that HHS and DHS identify ways that they can support manufacturers and the healthcare provider community in preparing and responding to future disasters and other supply disruptions in order to improve supply chain resilience. As part of these efforts, the group recommends exploring funding opportunities to support the continued flow of products needed during emergency situations should be examined.

Drug Shortages Roundtable: Minimizing Impact on Patient Care November 6, 2017 Page 9

9. Request electronic health records (EHR) vendors to employ changes to their systems to ease the burden of making drug product changes. In recent years, changes have been implemented across the healthcare system to improve patient safety, such as establishing more standardized practices. When a shortage occurs, however, it takes countless hours and staff-time to make a change to the EHR system. The group recommends a statement be crafted requesting that EHR vendors make changes to their systems to make it easier to switch products. 10. FDA should establish a quality manufacturing initiative. FDA should establish a manufacturing rating system where higher-quality manufacturing receives the higher rating. The FDA should consider incentives for manufacturers to participate in the program. The rating system should include factors such as whether the company has a contingency plan for interruptions/disasters and whether the company has a plan for redundancy in production. 11. FTC should include in its review of drug company merger proposals the potential risk for drug shortages. The number of drug companies making products widely used in hospitals and other healthcare settings is declining, particularly companies that produce generic sterile injectable products. This is due, in part, to continued consolidation among drug companies. We recommend that, among the factors the Federal Trade Commission considers in reviewing drug company mergers and acquisitions, it also consider the potential risk for drug shortages.

Conclusion

The group discussion largely focused on: (1) examining drug shortages over the past five years and assessing what has worked in terms of preventing and mitigating shortages as well as what could be improved, and (2) whether there have been notable changes in the causes of drug shortages, in the trends in the types of shortages, or in the marketplace dynamics that impact supply. In addition, the meeting provided an opportunity to hear from new potential stakeholders within ASPR on how the healthcare community can plan for future disasters and threats to critical infrastructure in order to minimize their impact on the supply of drugs. The recommendations listed above emerged out of these discussions.

Why was a railroad switch set in the wrong position sending an New York-to-Miami bound Amtrak train with more than 140 people aboard off the main line and onto a side track where it collided with an empty freight train early Sunday?

Sunday, February 4th, 2018Two people were killed and over 70 were injured in a crash involving a freight train and an Amtrak passenger train early Sunday in South Carolina.

Sunday, February 4th, 2018NASA: Precipitation in Western Europe from January 1 to 25, 2018.

Sunday, February 4th, 2018The animation below depicts satellite-based measurements of precipitation in Western Europe from January 1 to 25, 2018. The brightest areas reflect the highest precipitation amounts. The measurements are a product of the Global Precipitation Measurement (GPM) mission, which is a partnership between NASA, the Japan Aerospace Exploration Agency, and five other national and international partners.

These precipitation totals are regional, remotely-sensed estimates of precipitation (liquid and frozen mix); they do not reflect pure snowfall. Each pixel shows 0.1 degrees of the globe (about 7 miles at the equator), and the data are averaged across each pixel. Individual ground-based measurements within a pixel can be significantly higher or lower than the average.

In addition to the snowfall in the mountains, rainfall has been frequent and severe in the lowlands, particularly in France. The Seine River crested at nearly 6 meters (20 feet) in Paris in late January. The warm winter in Europe also means that a fair bit of snow has been melting off and running downstream, even as fresh snow is piling up in the hills.

-

References

- Meteo France (2018, January) Hiver 2018 : une pluviométrie exceptionnelle. Accessed January 31, 2018.

- The Washington Post (2018, January 23) Heavy snow and avalanches strand thousands at ski villages across the Alps. Accessed January 31, 2018.

- Weather.com (2018, January 23) Heavy Snow Buries Davos, Switzerland, During Meeting of World Leaders. Accessed January 31, 2018.

- Weather Underground (2018, January 27) Floods, Record Warmth, High Winds: It’s the Winter of 2018, European Edition. Accessed January 31, 2018.

NASA Earth Observatory images by Joshua Stevens, using MODIS data from LANCE/EOSDIS Rapid Response and IMERG data from the Global Precipitation Mission (GPM) at NASA/GSFC. Caption by Mike Carlowicz.

- Instrument(s):

- Terra – MODIS

- GPM

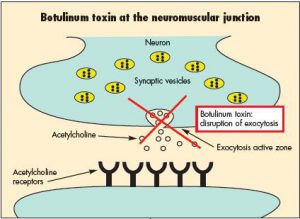

Researchers analyzing cow feces samples collected at a South Carolina farm discovered a strain of Enterococcus carrying a newtoxin similar to the one that causes botulism.

Sunday, February 4th, 2018“……“BoNT-like gene clusters have not previously been identified in any bacterial species outside of Clostridium and no toxins of E. faecium have been reported before now,” the authors said. “It is disconcerting to find a member of potent neurotoxins in this widely distributed gut microbe, which is a leading cause of hospital-acquired infections.”…..”

Outbreak of Seoul Virus Among Rats and Rat Owners — United States and Canada, 2017

Sunday, February 4th, 2018Kerins JL, Koske SE, Kazmierczak J, et al. Outbreak of Seoul Virus Among Rats and Rat Owners — United States and Canada, 2017. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2018;67:131–134. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.15585/mmwr.mm6704a5.

In December 2016, the Wisconsin Department of Health Services (WDHS) notified CDC of a patient hospitalized with fever, leukopenia, elevated transaminases, and proteinuria. The patient owned and operated an in-home rattery, or rat-breeding facility, with approximately 100 Norway rats, primarily bred as pets. A family member developed similar symptoms 4 weeks later, but was not hospitalized. Because both patients were known to have rodent contact, they were tested for hantavirus infections. In January 2017, CDC confirmed recent, acute Seoul virus infection in both patients. An investigation was conducted to identify additional human and rat infections and prevent further transmission. Ultimately, the investigation identified 31 facilities in 11 states with human and/or rat Seoul virus infections; six facilities also reported exchanging rats with Canadian ratteries. Testing of serum samples from 183 persons in the United States and Canada identified 24 (13.1%) with Seoul virus antibodies; three (12.5%) were hospitalized and no deaths occurred. This investigation, including cases described in a previously published report from Tennessee (1), identified the first known transmission of Seoul virus from pet rats to humans in the United States and Canada. Pet rat owners should practice safe rodent handling to prevent Seoul virus infection (2).

Seoul virus is an Old World hantavirus in the Bunyaviridae family. Its natural reservoir is the Norway rat (Rattus norvegicus). Rats infected with Seoul virus are asymptomatic, but can transmit the virus to humans through infectious saliva, urine, droppings, or aerosolization from contaminated bedding. Human signs and symptoms range from mild influenza-like illness to hemorrhagic fever with renal syndrome (HFRS). HFRS causes acute renal failure and can result in death; however, asymptomatic Seoul virus infections also occur. Wild Norway rats in the United States have been known to harbor Seoul virus infection (3), but transmission to humans is rare (4). Seoul virus is not known to spread from person to person. In the United Kingdom, Seoul virus transmission has occurred from pet rats to humans (5), but before this outbreak, infections had not been reported in pet rats in the United States or Canada.

Investigation and Results

After confirming Seoul virus infection in the Wisconsin patients, CDC and WDHS initiated investigations into rat shipments to (trace-back) and from (trace-forward) the rattery to identify suspected and confirmed facilities. Trace-back investigations initially extended back 2 months prior to onset of clinical disease, based on the known maximum incubation period for Seoul virus in humans. As additional confirmed facilities were identified, tracing focused instead on interactions with known infected facilities, sometimes as much as 1 year prior. Suspected facilities included ratteries, homes, or pet stores that sold rats to a confirmed facility (a facility where at least one human or rat tested positive for Seoul virus infection) or housed rats that lived at or comingled with rats from a confirmed facility. Once a suspected facility was identified, local or state health officials interviewed persons with a history of rodent contact associated with the facility about their rat exposure and health history. Additionally, the primary rodent caretaker was interviewed using a standardized questionnaire to identify movement of rats into and out of the facility, including dates and locations where the rats were obtained. Local or state health officials offered laboratory testing for Seoul virus infection to all persons with rodent contact. Officials recommended testing for persons with a history of febrile illness and exposure to rats from a confirmed facility and for rats at suspected and confirmed facilities. Trace-forward and trace-back investigations of rat shipments at confirmed facilities identified additional suspected facilities, which were similarly assessed.

A suspected human case of Seoul virus infection was defined as a febrile illness (recorded temperature >101°F [38.3°C] or subjective history of fever) or an illness clinically compatible with Seoul virus infection (myalgia, headache, renal failure, conjunctival redness, thrombocytopenia, or proteinuria) without laboratory confirmation in a person reporting contact with rats from a confirmed or suspected facility. Human Seoul virus infections were laboratory-confirmed by detection of Seoul virus-specific immunoglobulin M (IgM) and/or immunoglobulin G (IgG) (6) antibodies by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA). In the United States, Seoul virus infections in rats were confirmed through detection of viral RNA by reverse transcription–polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) and/or IgG ELISA at CDC, or by CDC-validated commercial IgG testing. In Canada, public health officials investigated rat breeding facilities that exported rats to and imported rats from affected U.S. facilities. Seoul virus infection was detected in Canadian rats from breeding facilities using the same serologic and molecular-based protocols described for United States facilities.

By March 16, 2017, trace-forward and trace-back investigations identified approximately 100 suspected facilities in 21 states. Among these, 31 facilities in 11 states* had laboratory-confirmed human or rat infections, including a previously reported household in Tennessee with two confirmed human infections (1). Six confirmed facilities in six states (Georgia, Illinois, Missouri, South Carolina, Tennessee, and Utah) reported exchanging rats with Canadian ratteries during their trace-forward and trace-back investigations. A total of 163 persons in the United States and 20 in Canada consented to serologic testing; 17 (10.4%) U.S. residents and one (5.0%) Canadian resident had detectable IgM and IgG antibodies, indicating recent infection, and four (2.5%) U.S. residents and two (10.0%) Canadian residents had only IgG antibodies, indicating past or convalescent infection. Among the 17 U.S. patients with recent Seoul virus infection, eight reported recent febrile illness. Three were hospitalized, but did not develop HFRS, and all recovered. Serious illness was not reported in any Canadian patients. All strains detected in Canada and the United States were indistinguishable from one another based on nucleotide sequencing (7), indicating that a single strain was responsible for the outbreak. No single facility was identified as the origin of the outbreak.

Public Health Response

On January 24, CDC issued a Health Alert Notice to notify health departments and health care providers of the Seoul virus investigations.† On February 20, the World Health Organization was notified of the U.S. and Canadian infections and investigations as required by International Health Regulations.§ On January 31 and May 9, 2017, CDC and the Pet Industry Joint Advisory Council hosted calls to provide updates on the Seoul virus outbreak and to answer questions for the pet industry and fancy rat community. CDC created a website with Seoul virus facts and frequently asked questions for the public.

Health departments notified suspected and confirmed facilities and placed those facilities under quarantine, allowing no rats to enter or leave. Rat contact was limited to as few persons as possible to reduce transmission. In suspected facilities, CDC recommended rat testing be performed under the supervision of a public health official or licensed veterinarian. The quarantine was lifted when at least 4 weeks had elapsed since the newest animal was introduced, and all rats subsequently tested negative. Rats belonging to owners who refused to test their animals could remain quarantined for life or be euthanized. CDC recommended euthanasia of all rats in confirmed facilities as the most effective method to prevent transmission, although control recommendations differed by state and country according to local policies and response capacities. If euthanasia was not possible, then owners could either quarantine all rats for life or pursue quarantine with testing and culling. The testing and culling strategy entailed testing all rats and euthanizing only infected rats. Testing and euthanasia were repeated at 4 week intervals until all rats tested negative and the quarantine was lifted. In Canada, public health officials opted for education and a voluntary testing and culling approach to control Seoul virus transmission.

Discussion

This outbreak report, in parallel to the previously described investigation in Tennessee (1), describes the first known cases of Seoul virus infection in humans attributable to contact with pet rats in the United States and Canada. Human hantavirus infections are nationally notifiable in the United States and suspected cases should be reported to state or local health departments. Health care providers should consider Seoul virus infection in patients with febrile illness who report rat exposure; CDC recommends testing for any person with compatible illness and rodent contact. Testing is available at CDC¶ and through some state and commercial laboratories. In Canada, testing is available for symptomatic persons with rat exposure, rattery owners associated with this investigation, and their rats through public health laboratories; for individually owned pet rats and ratteries not associated with the investigation, testing is available through a commercial laboratory.

Pet rat owners should be aware of the potential for Seoul virus infection. To keep themselves and their pets healthy, all persons with rodent contact should avoid bites or scratches and practice good hand hygiene, especially children and persons with compromised immune systems (2). CDC recommends hand washing after caring for rodents and before eating, drinking, or preparing food (2). If a pet rat is suspected of having Seoul virus, the person cleaning the rodent environment should wear a respirator, gloves, and cover any scratches or open wounds (8). An adult should routinely disinfect rat cages and accessories, including used bedding, with a 10% bleach solution or a commercial disinfectant (8). More information about rodent contact and disease prevention is available from CDC (8,9).

Rattery owners are encouraged to quarantine any newly acquired rats for 4 weeks and to test these rats for Seoul virus antibodies before allowing them to comingle with other rats. Commercial laboratories can perform Seoul virus testing of rodent blood samples, and comparisons of results from shared samples have been concordant with CDC’s ELISA and RT-PCR assays. To prevent transmission to humans, CDC recommends euthanasia of all rats in facilities with human or rat Seoul virus infections. Further guidance on methods to eradicate Seoul virus from infected ratteries should be obtained from local or state health departments.

References

- Fill MA, Mullins H, May AS, et al. Notes from the field: multiple cases of Seoul virus infection in a household with infected pet rats—Tennessee, December 2016–April 2017. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2017;66:1081–2. CrossRef PubMed

- CDC. Key messages about pet rodents. Atlanta, GA: US Department of Health and Human Services, CDC; 2017. https://www.cdc.gov/healthypets/pets/small-mammals/petrodents.html

- Childs JE, Korch GW, Smith GA, Terry AD, Leduc JW. Geographical distribution and age related prevalence of antibody to Hantaan-like virus in rat populations of Baltimore, Maryland, USA. Am J Trop Med Hyg 1985;34:385–7. CrossRef PubMed

- Knust B, Rollin PE. Twenty-year summary of surveillance for human hantavirus infections, United States. Emerg Infect Dis 2013;19:1934–7 . CrossRef PubMed

- Jameson LJ, Taori SK, Atkinson B, et al. Pet rats as a source of hantavirus in England and Wales, 2013. Euro Surveill 2013;18:20415. PubMed

- Ksiazek TG, West CP, Rollin PE, Jahrling PB, Peters CJ. ELISA for the detection of antibodies to Ebola viruses. J Infect Dis 1999;179(Suppl 1):S192–8. CrossRef PubMed

- Woods C, Palekar R, Kim P, et al. Domestically acquired Seoul virus causing hemorrhagic fever with renal syndrome—Maryland, 2008. Clin Infect Dis 2009;49:e109–12. CrossRef PubMed

- CDC. Cleaning up after pet rodents to reduce the risk of Seoul virus infection. Atlanta, GA: US Department of Health and Human Services, CDC; 2017. https://www.cdc.gov/hantavirus/outbreaks/seoul-virus/cleaning-up-pet-rodents.html

- CDC. Healthy pets healthy people. Atlanta, GA: US Department of Health and Human Services, CDC; 2017. https://www.cdc.gov/healthypets/