Archive for December, 2018

Pakistan: An ongoing outbreak of extensively drug resistant (XDR) typhoid fever

Monday, December 31st, 2018Typhoid fever – Islamic Republic of Pakistan

Pakistan Health Authorities have reported an ongoing outbreak of extensively drug resistant (XDR) typhoid fever that began in the Hyderabad district of Sindh province in November 2016. An increasing trend of typhoid fever cases caused by antimicrobial resistant (AMR) strains of Salmonella enterica serovar Typhi (or S. Typhi) poses a notable public health concern. In May 2018, the case definitions for non-resistant, multi-drug resistant (MDR) and XDR typhoid fever were formally agreed by the Regional Disease Surveillance and Response Unit (RDSRU) in Karachi, following a review by an expert group of epidemiologists, clinicians and microbiologists from Pakistan. All typhoid fever cases reported from 2016 to 2018 were reviewed and classified according to these case definitions (see Table 1).

Table 1. Classification of Typhoid Fever Cases by Drug Resistance Status, Pakistan, 2018

From 1 November 2016 through 9 December 2018, 5 274 cases of XDR typhoid out of 8 188 typhoid fever cases were reported by the Provincial Disease Surveillance and Response Unit (PDSRU) in Sindh province, Pakistan. Sixty-nine percent of cases were reported in Karachi (the capital city), 27% in Hyderabad district, and 4% in other districts in the province (Table 2). The circulating XDR strain of S. Typhi haplotype 58 was resistant to first and second-line antibiotics as well as third generation cephalosporins. Informal reports of XDR typhoid cases occurring in other parts of Pakistan were made and required further verification.

Table 2. Distribution of reported XDR typhoid fever cases in Sindh Province, Pakistan [1 November 2016 through 9 December 2018]

In addition, from January to October 2018, there were reports indicating international transmission of the XDR typhoid strain through persons who had travelled to Pakistan. Six travel-associated cases of XDR typhoid were reported; one in the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland, and five in the United States of America. Four of the travel-associated cases had visited or resided in Karachi (Sindh province), Lahore (Punjab province) and/or Islamabad in Pakistan. Details regarding these four cases are as follows:

- Two of the cases travelled to Karachi, Lahore, and Islamabad.

- One case travelled only to Karachi.

- One case pending confirmation, is a resident from Lahore with travel history to the US where he/she was diagnosed and treated. The case has since returned to Pakistan.

Limited information is available about their mechanism of exposure or the exact date of onset of illness for these cases but, there are evidence that all the travel-associated cases were successfully treated.

Public health response

In January 2017, the Government of Pakistan initiated a public health response to the increasing number of XDR typhoid fever cases in Sindh province. The resulting activities included:

- Community and school awareness campaigns on safe hygiene and sanitation practices were carried out in Hyderabad, including specific health education on hand hygiene, use of safe drinking water, and environmental sanitation.

- Water purification and sanitation activities were implemented, including distribution of chlorine tablets to affected communities in Hyderabad.

- General practitioners and clinicians in Hyderabad were sensitized on the rational use of antimicrobials for typhoid fever by the Department of Health and partners, with support from the WHO.

- A typhoid vaccination campaign was commenced on 5 August 2017 in Hyderabad with Vi-polysaccharide typhoid vaccine (ViPS). Approximately 6000 children aged 6 months to 10 years, were vaccinated. A subsequent mass vaccination campaign with typhoid conjugate vaccine (TCV) was launched in Hyderabad in January 2018, resulting in approximately 118 000 children, aged 6 months to 10 years being vaccinated to date. The government of Pakistan also applied for GAVI support for a three-year phased TCV introduction into the routine National Program on Immunization, starting from 2019. Prior to the introduction, phased catch-up campaigns in urban areas will be conducted. The target age group for this activity is children aged 9 months to 15 years.

- XDR National Taskforce was established in July 2018, and a joint WHO and United States Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (US CDC) mission was founded. Recommendations these collaborations are currently being translated into a draft national action plan in Pakistan.

- Updated surveillance tools and a line listing template for data collection on typhoid cases were shared with all the provincial departments of health on 7 September 2018. The purpose of this was to collect additional information and enhance surveillance, particularly about the occurrence and spread of XDR typhoid to other parts of Pakistan, and beyond.

WHO has been leading initiatives to make a sustained difference in the continuing problem of antimicrobial resistance (AMR). These initiatives include:

- The Global Antimicrobial Resistance Surveillance System (GLASS): A standardized approach to the collection, analysis and sharing of data related to antimicrobial resistance (AMR), including reports of emerging resistance via GLASS-EAR (Emerging Antimicrobial Resistance). The purpose of this activity was to inform decision-making and drive local, national and regional action.

- WHO supported the XDR National Task Force in Pakistan, chaired by the Director-General of Health, in the development of the National Action Plan on AMR1.

- Global Antibiotic Research and Development Partnership (GARDP): A joint initiative of WHO and Drugs for Neglected Diseases initiative (DNDi) which encourages public-private research partnerships, including on typhoid fever.

WHO risk assessment

The risk of XDR S. Typhi at the national level is considered high in Pakistan due to insufficient water, poor sanitation and hygiene (WASH) practices, low vaccination coverage and limited surveillance for typhoid fever. The fact that AMR S. Typhi confirmatory testing and antimicrobial susceptibility testing is only conducted by major laboratories and tertiary care hospitals are other priority considerations in terms of risk. These factors, coupled with sub-optimal antibiotic prescribing practices, have limited the ability to track the occurrence, spread, and containment of XDR S. Typhi.

Outbreaks of MDR typhoid and sporadic cases of infection with ceftriaxone-resistant S. Typhi have been reported in several countries. However, this is the first time a large outbreak caused by XDR S. Typhi has been observed in Pakistan.

The risk at regional level is considered moderate due to the similar environments and approaches to treatment of typhoid fever, as well as the widespread over-use of anti-microbials which is compounded by considerable levels of migration within the region.

Globally, the risk is considered low due to the availability of antimicrobials and rational prescribing practices. However, S. Typhi has a global distribution and the potential for travelers to spread this resistant clone, especially in countries with poor WASH infrastructure, cannot be eliminated. The high level of resistance to traditional first-line antibiotics in the H58 clonal strain identified to be circulating in parts of Pakistan increases the potential risk at all three levels.

WHO recommendations

This outbreak highlights the importance of public health measures to prevent the spread of resistant and non-resistant pathogens. While the emerging resistance in S. Typhi complicates treatment, typhoid fever remains common in places with poor sanitation and a lack of safe drinking water. Access to safe water and adequate sanitation, hygiene among food handlers, and typhoid vaccination are the main and most important recommendations.

WHO recommends typhoid vaccination in response to confirmed outbreaks of typhoid fever, and travelers to typhoid-endemic areas should consider vaccination. Further, where the TCV is licensed, WHO recommends TCV as the preferred typhoid vaccine. Typhoid vaccination should be implemented in combination with other efforts to control the disease.

In view of the observed capacity for S. Typhi to quickly acquire new resistance mechanisms, WHO recommends strengthening surveillance of typhoid fever, including surveillance of AMR to monitor known resistance, detect new and emerging resistance, and mitigate its spread. WHO also recommends that surveillance data is shared locally and internationally in a timely manner.

Currently, azithromycin is the only remaining reliable and affordable first-line oral therapeutic option to manage patients with XDR typhoid in low-resource settings. Patients with suspected typhoid fever should be tested microbiologically to detect S. Typhi and define antimicrobial susceptibility wherever possible to inform patient management and contribute to the surveillance efforts. Verification and advanced testing (including molecular methods) of S. Typhi strains with unusual resistance should be performed by designated expert laboratories that provide confirmatory testing, where such capacity exists within countries. In countries where no laboratory capacity currently exists, regional collaboration may be an option, whereby a neighbouring country’s reference laboratory or a WHO Collaborating Center can fulfill this role.

For more information:

- WHO recommends use of first typhoid conjugate vaccine

- Antimicrobial Resistance in Typhoid: implications for policy & immunization strategies

- Surveillance standards recently published by WHO “Typhoid and other invasive salmonellosis”

- Antimicrobial Resistance, National Action Plan, Pakistan

1 Chloramphenicol, ampicillin, trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole

2 Cefixime is recommended by the International Academy of the Philippines (IAP) for uncomplicated typhoid fever. Ceftriaxone is recommended for complicated typhoid fever.

3 Fluoroquinolones

4 First and second-line drugs, and third generation cephalosporins

5 http://www.nih.org.pk/wp-content/uploads/2018/08/AMR-National-Action-Plan-Pakistan.pdf

Ebola in DRC: case total climbs to 593

Monday, December 31st, 2018Ebola virus disease – Democratic Republic of the Congo

The Ministry of Health (MoH), WHO and partners continue to respond to the Ebola virus disease (EVD) outbreak in the Democratic Republic of the Congo. While communities in affected areas are generally supportive of the Ebola response, operations in some areas have been temporarily disrupted due to insecurity. On 27 December 2018, protests at government buildings in Beni spilled over to an Ebola transit centre, frightening people waiting for Ebola test results and the staff who were caring for them. Staff at the centre temporarily withdrew and most suspected cases were transferred to a nearby treatment centre. WHO is concerned about the negative effects that the current insecurity is having on efforts to control the outbreak. After an intensification of field activities, marked improvements in controlling the outbreak were observed in many areas, including a recent decrease in cases in Beni. These gains could be lost if we suffer a period of prolonged insecurity that results in increased Ebola virus transmission. While maintaining focus on ending the outbreak and resuming normal operations as soon as possible, all response partners remain committed to ensuring the safety of staff. WHO continues to monitor the situation closely and will adapt their response as needed.

As of 26 December 2018, a total of 591 EVD cases, including 543 confirmed and 48 probable cases, have been reported from 16 health zones in the two neighbouring provinces of North Kivu and Ituri (Figure 1). Of these cases, 54 were healthcare workers, of which 18 died. Overall, 357 cases have died (case fatality ratio 60%). In the past week, ten additional patients were discharged from Ebola treatment centres; overall, 203 patients have recovered to date. The highest number of cases were from age group 15‒49 years with 60% (355/589) of the cases, and of those, 228 were female. Highest attack rates have been observed in children aged more than one year (especially male infants) and females aged 15 years and older.

Trends in case incidence (Figure 2) reflect the continuation of the outbreak across these geographically dispersed areas. The general decrease in the weekly incidence observed in Beni since late October continued; however, the outbreak is intensifying in Butembo and Katwa, and new clusters have emerged in other health zones. Thirteen health zones reported a total of 109 confirmed cases in the last 21 days (5‒26 December 2018). The majority of which were concentrated in major urban centres and towns in Katwa (26), Komanda (21), Mabalako (15), Beni (14) and Butembo (10) health zones. An isolated case was also recently detected in Nyankunde Health Zone – a newly affected area in Ituri Province – whom likely acquired the infection in Komanda. This case, highlights the continued high risk of continued spread of the outbreak and the need to strengthen all aspects of the response in Ituri, North Kivu and surrounding provinces and countries.

The MoH, WHO and partners continue to monitor and investigate all alerts in affected areas, in other provinces in the Democratic Republic of the Congo, and in neighbouring countries. Since the last report was published, alerts were investigated in several provinces of the Democratic Republic of the Congo as well as in Uganda. To date, EVD has been ruled out in all alerts outside of the abovementioned outbreak affected areas.

Figure 1: Confirmed and probable Ebola virus disease cases by health zone in North Kivu and Ituri provinces, Democratic Republic of the Congo, data as of 26 December 2018 (n=591)

Figure 1: Confirmed and probable Ebola virus disease cases by health zone in North Kivu and Ituri provinces, Democratic Republic of the Congo, data as of 26 December 2018 (n=591)

Figure 2: Confirmed and probable Ebola virus disease cases by week of illness onset, data as of 26 December 2018 (n=591)*

*Data in recent weeks are subject to delays in case confirmation and reporting, as well as ongoing data cleaning – trends during this period should be interpreted cautiously.

Public health response

The MoH continues to strengthen response measures, with support from WHO and partners. Priorities include coordination, surveillance, contact tracing, laboratory capacity, infection prevention and control (IPC), clinical management of patients, vaccination, risk communication and community engagement, psychosocial support, safe and dignified burials (SDB), cross-border surveillance, and preparedness activities in neighbouring provinces and countries. Infection prevention and control practices in health care facilities, especially antenatal clinics, need to be further strengthened.

For detailed information about the public health response actions by WHO and partners, please refer to the latest situation reports published by the WHO Regional Office for Africa:

WHO risk assessment

This outbreak of EVD is affecting north-eastern provinces of the country bordering Uganda, Rwanda and South Sudan. Potential risk factors for transmission of EVD at the national and regional levels include: travel between the affected areas, the rest of the country, and neighbouring countries; the internal displacement of populations. The country is concurrently experiencing other epidemics (e.g. cholera, vaccine-derived poliomyelitis, malaria), and a long-term humanitarian crisis. Additionally, the security situation in North Kivu and Ituri at times limits the implementation of response activities. WHO’s risk assessment for the outbreak is currently very high at the national and regional levels; the global risk level remains low. WHO continues to advice against any restriction of travel to, and trade with, the Democratic Republic of the Congo based on currently available information.

As the risk of national and regional spread is very high, it is important for neighbouring provinces and countries to enhance surveillance and preparedness activities. The International Health Regulations (IHR 2005) Emergency Committee has advised that failing to intensify these preparedness and surveillance activities would lead to worsening conditions and further spread. WHO will continue to work with neighbouring countries and partners to ensure that health authorities are alerted and are operationally prepared to respond.

WHO advice

International traffic: WHO advises against any restriction of travel and trade to the Democratic Republic of the Congo based on the currently available information. There is currently no licensed vaccine to protect people from the Ebola virus. Therefore, any requirements for certificates of Ebola vaccination are not a reasonable basis for restricting movement across borders or the issuance of visas for passengers leaving the Democratic Republic of the Congo. WHO continues to closely monitor and, if necessary, verify travel and trade measures in relation to this event. Currently, no country has implemented travel measures that significantly interfere with international traffic to and from the Democratic Republic of the Congo. Travellers should seek medical advice before travel and should practice good hygiene.

For more information, see:

- Democratic Republic of the Congo begins first-ever multi-drug Ebola trial

- South Sudan set to vaccinate targeted healthcare and frontline workers operating in high risk states against Ebola

- Summary report for the SAGE meeting of October 2018

- Statement on the October 2018 meeting of the IHR Emergency Committee on the Ebola virus disease outbreak in the Democratic Republic of the Congo

- WHO Interim recommendation Ebola vaccines

- WHO recommendations for international travellers related to the Ebola Virus Disease outbreak in the Democratic Republic of the Congo

- Ebola virus disease in the Democratic Republic of the Congo – Operational readiness and preparedness in neighbouring countries

- Ebola virus disease fact sheet

1The number of cases is subject to change due to ongoing reclassification, retrospective investigation, and the availability of laboratory results.

Saudi Arabia: 8 MERS-CoV cases, two of them fatal, between Oct 31 and Nov 30.

Monday, December 31st, 2018Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus (MERS-CoV) – Saudi Arabia

From 31 October through 30 November 2018, the International Health Regulations (IHR 2005) National Focal Point of Saudi Arabia reported eight additional cases of Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus (MERS-CoV) infection, including two deaths. Details of these cases can be found in a separate document (see link below).

From 2012 through 30 November 2018, the total number of laboratory-confirmed MERS-CoV cases reported globally to WHO under IHR (2005) is 2274 with 806 associated deaths. The total number of deaths includes the deaths that WHO is aware of to date through follow-up with affected member states.

WHO risk assessment

Infection with MERS-CoV can cause severe disease resulting in high mortality. Humans are infected with MERS-CoV from direct or indirect contact with dromedary camels. MERS-CoV has demonstrated the ability to transmit between humans. So far, the observed non-sustained human-to-human transmission has occurred mainly in health care settings.

The notification of additional cases does not change the overall risk assessment. WHO expects that additional cases of MERS-CoV infection will be reported from the Middle East, and that cases will continue to be exported to other countries by individuals who might acquire the infection after exposure to animals, animal products (for example, following contact with camels), or humans (for example, in a health care setting). WHO continues to monitor the epidemiological situation and conducts risk assessment based on the latest available information.

WHO advice

Based on the current situation and available information, WHO encourages all Member States to continue their surveillance for acute respiratory infections and to carefully review any unusual patterns.

Infection prevention and control measures are critical to prevent the possible spread of MERS-CoV in health care facilities. It is not always possible to identify patients with MERS-CoV early because like other respiratory infections, the early symptoms of MERS-CoV are non-specific. Therefore, healthcare workers should always apply standard precautions consistently with all patients, regardless of their diagnosis. Droplet precautions should be added to the standard precautions when providing care to patients with symptoms of acute respiratory infection; contact precautions and eye protection should be added when caring for probable or confirmed cases of MERS-CoV infection; airborne precautions should be applied when performing aerosol generating procedures.

MERS-CoV appears to cause more severe disease in people with diabetes, renal failure, chronic lung disease, and immunocompromised persons. Therefore, these people should avoid close contact with animals, particularly camels, when visiting farms, markets, or barn areas where the virus is known to be potentially circulating. General hygiene measures, such as regular hand washing before and after touching animals and avoiding contact with sick animals, should be adhered to. Food hygiene practices should be observed. People should avoid drinking raw camel milk or camel urine, or eating meat that has not been properly cooked.

WHO does not advise special screening at points of entry with regard to this event nor does it currently recommend the application of any travel or trade restrictions.

12/30/1903, the deadliest theater fire in U.S. history: A fire in the Iroquois Theater in Chicago, Illinois, kills more than 600 people.

Sunday, December 30th, 2018Influenza activity in the United States is increasing. Influenza A(H1N1)pdm09, influenza A(H3N2), and influenza B viruses continue to co-circulate.

Sunday, December 30th, 2018Synopsis:

Influenza activity in the United States is increasing. Influenza A(H1N1)pdm09, influenza A(H3N2), and influenza B viruses continue to co-circulate. Below is a summary of the key influenza indicators for the week ending December 22, 2018:

- Viral Surveillance: Influenza A viruses have predominated in the United States since the beginning of October. Influenza A(H1N1)pdm09 viruses have predominated in most areas of the country, however influenza A(H3) viruses predominated in the southeastern United States (HHS Region 4). The percentage of respiratory specimens testing positive for influenza viruses in clinical laboratories is increasing.

- Virus Characterization: The majority of influenza viruses characterized antigenically and genetically are similar to the cell-grown reference viruses representing the 2018–2019 Northern Hemisphere influenza vaccine viruses. A comparison of gene sequences of recent influenza A(H1N1)pdm09 viruses from the U.S. and Mexico/Central America showed them to be similar.

- Antiviral Resistance: All viruses tested show susceptibility to the neuraminidase inhibitors (oseltamivir, zanamivir, and peramivir).

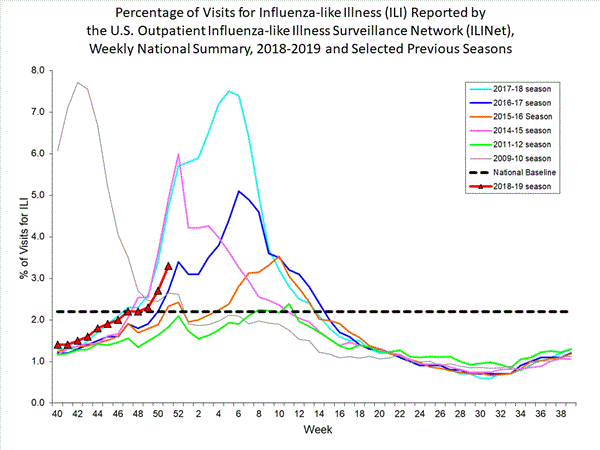

- Influenza-like Illness Surveillance:The proportion of outpatient visits for influenza-like illness (ILI) increased to 3.3%, which is above the national baseline of 2.2%. Nine of 10 regions reported ILI at or above their region-specific baseline level.

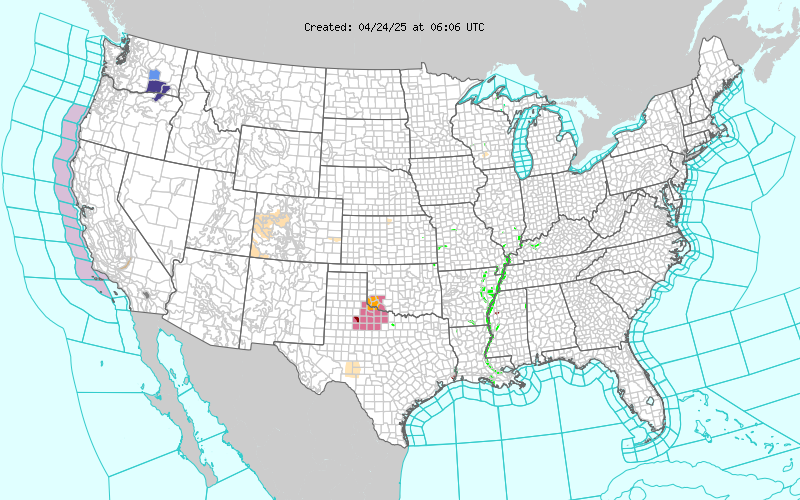

- ILI State Activity Indictor Map: New York City and nine states experienced high ILI activity; Puerto Rico and seven states experienced moderate ILI activity; 11 states experienced low ILI activity; the District of Columbia and 22 states experienced minimal ILI activity; and one state had insufficient data. Among the four states along the southern U.S. border, ILI activity increased to moderate in Arizona and high in New Mexico.

- Geographic Spread of Influenza: The geographic spread of influenza in Guam and 11 states was reported as widespread; Puerto Rico and 19 states reported regional activity; 15 states reported local activity; the District of Columbia, the U.S. Virgin Islands and three states reported sporadic activity; and two states did not report.

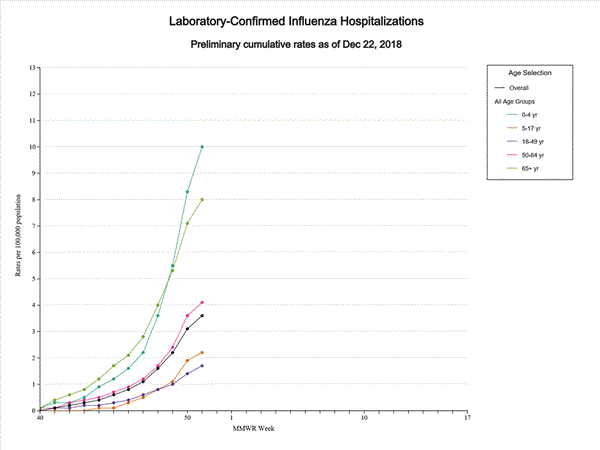

- Influenza-associated Hospitalizations A cumulative rate of 3.6 laboratory-confirmed influenza-associated hospitalizations per 100,000 population was reported. The highest hospitalization rate is among children younger than 5 years (10.0 hospitalizations per 100,000 population).

- Pneumonia and Influenza Mortality: The proportion of deaths attributed to pneumonia and influenza (P&I) was below the system-specific epidemic threshold in the National Center for Health Statistics (NCHS) Mortality Surveillance System.

- Influenza-associated Pediatric Deaths: Four influenza-associated pediatric deaths were reported to CDC during week 51.

The hump-nosed pit viper (Hypnale hypnale)

Sunday, December 30th, 2018

Kumar KS, Narayanan S, Udayabhaskaran V, Thulaseedharan NK.

Clinical and epidemiologic profile and predictors of outcome of poisonous snake bites – an analysis of 1,500 cases from a tertiary care center in Malabar, North Kerala, India. Int J Gen Med. 2018;11:209-216. Published 2018 Jun 5. doi:10.2147/IJGM.S136153

- No antidote available for its deadly venom.

- Also called the hump-nosed moccasin for its pointed and upturned snout

- A major killer endemic to the Western Ghats, a mountain range of South India, and Sri Lanka.

- The standard polyvalent antivenom used for the four most poisonous snakes of the region — the Indian cobra (Naja naja), Indian krait (Bangarus caeruleus), Russell’s viper (Daboia russelii) and saw-scaled viper (Echis carinatus) — does not work on hump-nosed pit viper venom.

- Hump-nosed pit viper envenomation typically brings on acute kidney injury leading to corticoid necrosis and death

Black mamba: One of the most feared snake species of the African savanna.

Sunday, December 30th, 2018In vivo neutralization of dendrotoxin-mediated neurotoxicity of black mamba venom by oligoclonal human IgG antibodies

Nature Communications volume 9, Article number: 3928 (2018)

“…..The black mamba (Dendroaspis polylepis) is one of the most feared snake species of the African savanna. It has a potent, fast-acting neurotoxic venom comprised of dendrotoxins and α-neurotoxins associated with high fatality in untreated victims. Current antivenoms are both scarce on the African continent and present a number of drawbacks as they are derived from the plasma of hyper-immunized large mammals…..”

- “…Snakebite envenoming exacts a death toll of 80–150,000 victims each year, leaves approximately four times as many maimed for life1, and has recently been recognized as a Neglected Tropical Disease by the World Health Organization (WHO)….”

- “:…..The notorious black mamba (Dendroaspis polylepis) from sub-Saharan Africa is a particularly dangerous species due to its size, defensive nature, and fast-acting neurotoxic venom. Life threatening clinical manifestations of D. polylepis envenoming include flaccid paralysis due to blockade of neuromuscular transmission resulting from inhibition of nicotinic acetylcholine receptors in the peripheral nervous system caused by α-neurotoxins (both short-chain and long-chain types) of the three-finger toxin superfamily….”