Archive for the ‘Anaplasmosis’ Category

At a crossroads for Lyme and other serious tick-borne diseases in the U.S.

Wednesday, August 21st, 2019“…….In 2017, mosquito-borne West Nile virus, which currently infects about 2,000 people annually in the U.S. received $42 million in support from the U.S. National Institutes of Health. Lyme disease, with 20 times the number of reported cases, got half as much, a figure that has changed little in a decade. ……..Lyme disease from black-legged ticks is only a part of the problem. Cases of anaplasmosis and ehrlichiosis have soared, increasing sixfold since 2004. Malaria-like babesiosis, once limited to coastal islands, has been reported in 27 states; it makes Lyme disease far worse. The lone star tick, common in the South, has migrated to vast tracts of new territory as the climate has warmed, its bite causing a potentially severe meat allergy unheard of a decade ago. In 2017 the Asian longhorned tick became the first new tick species in the U.S. in 80 years. Now in 11 states, the ticks so infested five cows in North Carolina recently that they died of anemia from blood loss. The implications for agriculture could be dire because female longhorned ticks can clone themselves, vastly increasing birthrates. …..”

Where found: Widely distributed east of the Rocky Mountains. Also occurs in limited areas on the Pacific Coast.

Transmits: Tularemia and Rocky Mountain spotted fever.

Comments: The highest risk of being bitten occurs during spring and summer. Dog ticks are sometimes called wood ticks. Adult females are most likely to bite humans.

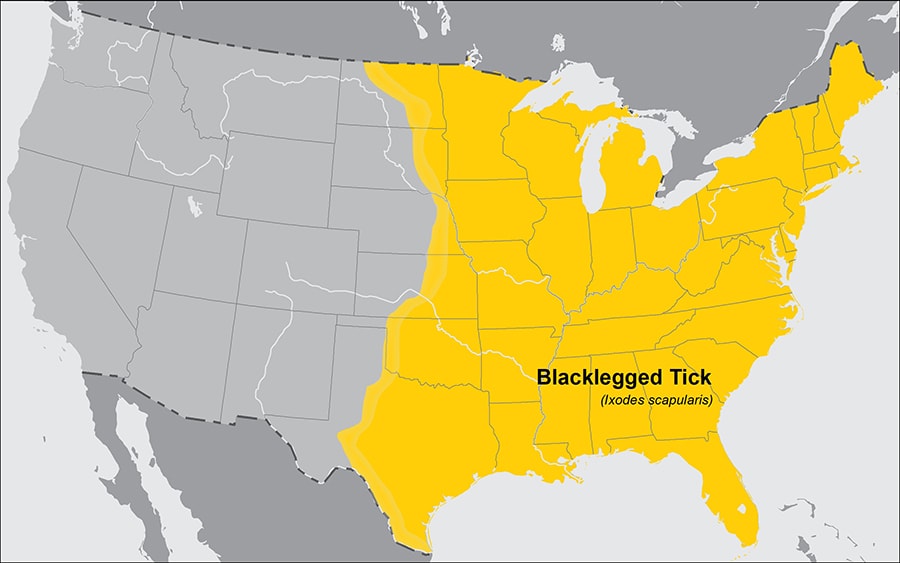

Where found: Widely distributed across the eastern United States.

Transmits: Borrelia burgdorferi and B. mayonii (which cause Lyme disease), Anaplasma phagocytophilum (anaplasmosis), B. miyamotoi disease (a form of relapsing fever), Ehrlichia muris eauclairensis (ehrlichiosis), Babesia microti (babesiosis), and Powassan virus (Powassan virus disease).

Comments: The greatest risk of being bitten exists in the spring, summer, and fall. However, adults may be out searching for a host any time winter temperatures are above freezing. Stages most likely to bite humans are nymphs and adult females.

Where found: Worldwide.

Where found: Worldwide.

Transmits: Rocky Mountain spotted fever (in the southwestern U.S. and along the U.S.-Mexico border).

Comments: Dogs are the primary host for the brown dog tick in each of its life stages, but the tick may also bite humans or other mammals.

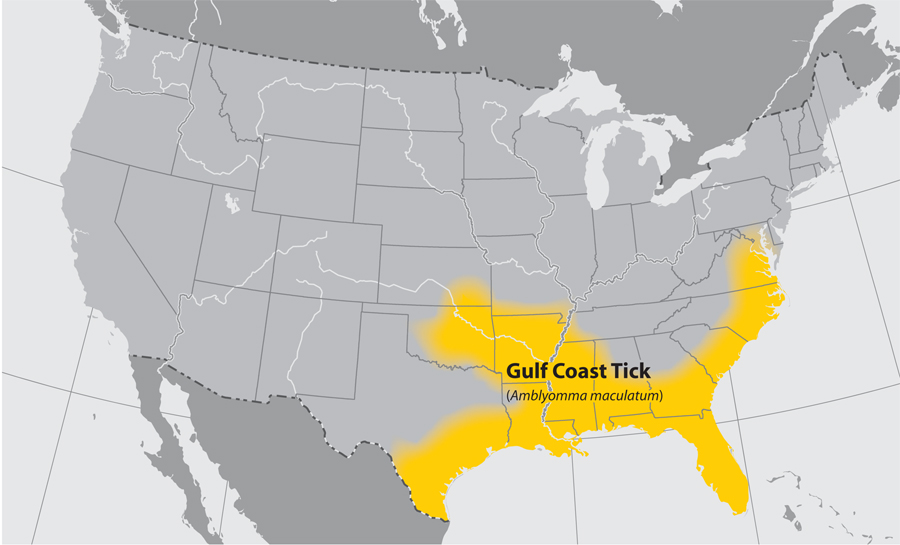

Where found: Coastal areas of the U.S. along the Atlantic coast and the Gulf of Mexico.

Transmits: Rickettsia parkeri rickettsiosis, a form of spotted fever.

Comments: Larvae and nymphs feed on birds and small rodents, while adult ticks feed on deer and other wildlife. Adult ticks have been associated with transmission of R. parkeri to humans.

Where found: Widely distributed in the southeastern and eastern United States.

Transmits: Ehrlichia chaffeensis and Ehrlichia ewingii (which cause human ehrlichiosis), Heartland virus, tularemia, and STARI.

Comments: A very aggressive tick that bites humans. The adult female is distinguished by a white dot or “lone star” on her back. Lone star tick saliva can be irritating; redness and discomfort at a bite site does not necessarily indicate an infection. The nymph and adult females most frequently bite humans and transmit disease.

Where found: Rocky Mountain states and southwestern Canada from elevations of 4,000 to 10,500 feet.

Where found: Rocky Mountain states and southwestern Canada from elevations of 4,000 to 10,500 feet.

Transmits: Rocky Mountain spotted fever, Colorado tick fever, and tularemia.

Comments: Adult ticks feed primarily on large mammals. Larvae and nymphs feed on small rodents. Adult ticks are primarily associated with pathogen transmission to humans.

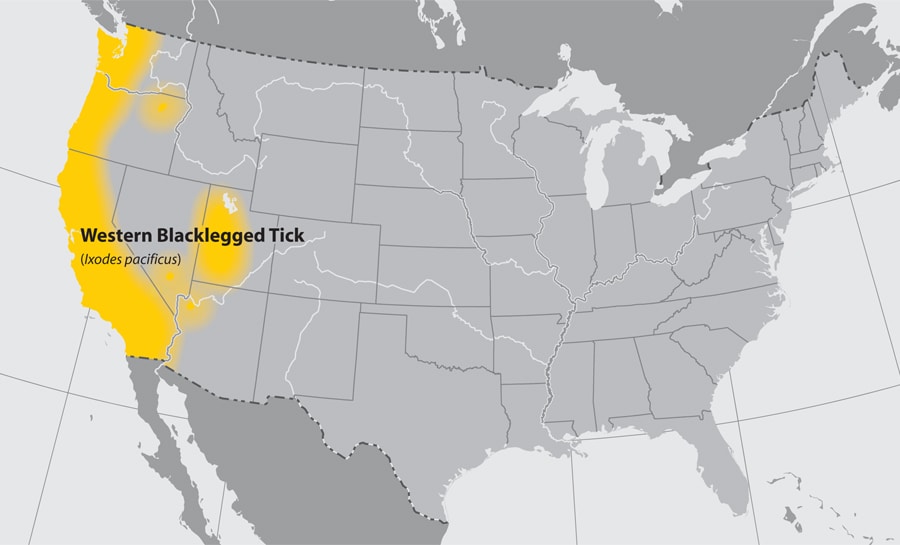

Where found: Along the Pacific coast of the U.S., particularly northern California.

Where found: Along the Pacific coast of the U.S., particularly northern California.

Transmits: Anaplasmosis and Lyme disease.

Comments: Nymphs often feed on lizards, as well as other small animals. As a result, rates of infection are usually low (~1%) in adults. Stages most likely to bite humans are nymphs and adult females.

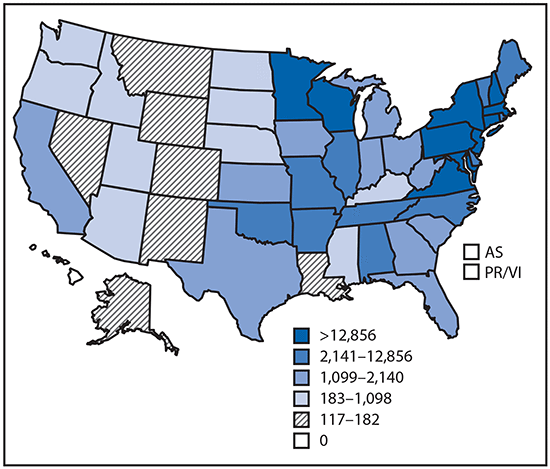

U.S. trends in occurrence of nationally reportable vectorborne diseases during 2004–2016.

Wednesday, May 2nd, 2018Rosenberg R, Lindsey NP, Fischer M, et al. Vital Signs: Trends in Reported Vectorborne Disease Cases — United States and Territories, 2004–2016. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. ePub: 1 May 2018. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.15585/mmwr.mm6717e1.

Key Points

•A total of 642,602 cases of 16 diseases caused by bacteria, viruses, or parasites transmitted through the bites of mosquitoes, ticks, or fleas were reported to CDC during 2004–2016. Indications are that cases were substantially underreported.

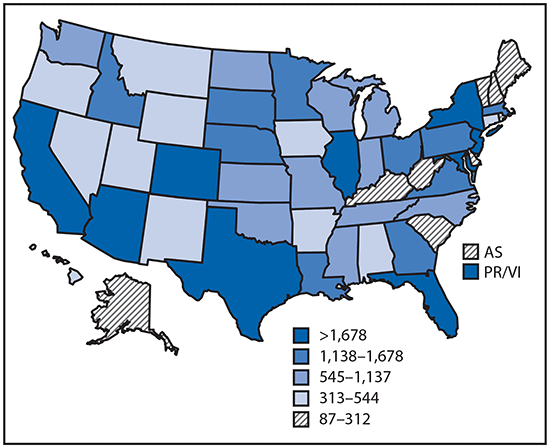

•Tickborne diseases more than doubled in 13 years and were 77% of all vectorborne disease reports. Lyme disease accounted for 82% of all tickborne cases, but spotted fever rickettsioses, babesiosis, and anaplasmosis/ehrlichiosis cases also increased.

•Tickborne disease cases predominated in the eastern continental United States and areas along the Pacific coast. Mosquitoborne dengue, chikungunya, and Zika viruses were almost exclusively transmitted in Puerto Rico, American Samoa, and the U.S. Virgin Islands, where they were periodically epidemic. West Nile virus, also occasionally epidemic, was widely distributed in the continental United States, where it is the major mosquitoborne disease.

•During 2004–2016, nine vectorborne human diseases were reported for the first time from the United States and U.S. territories. The discovery or introduction of novel vectorborne agents will be a continuing threat.

•Vectorborne diseases have been difficult to prevent and control. A Food and Drug Administration–-approved vaccine is available only for yellow fever virus. Many of the vectorborne diseases, including Lyme disease and West Nile virus, have animal reservoirs. Insecticide resistance is widespread and increasing.

•Preventing and responding to vectorborne disease outbreaks are high priorities for CDC and will require additional capacity at state and local levels for tracking, diagnosing, and reporting cases; controlling vectors; and preventing transmission.

Reported cases* of tickborne disease — U.S. states and territories, 2004–2016

Reported cases* of mosquitoborne disease — U.S. states and territories, 2004–2016

Reported nationally notifiable mosquitoborne,* tickborne, and fleaborne† disease cases — U.S. states and territories, 2004–2016

Vermont: 133 cases of anaplasmosis have been reported so far this year

Saturday, October 1st, 2016Anaplasmosis is a disease caused by infection of the bacterium, Anaplasma phagocytophilum. In the eastern United States, the disease is spread by the bite of an infected black-legged tick, Ixodes scapularis. This is the same tick that can transmit Lyme disease. Anaplasmosis is also known as human granulocytic anaplasmosis (HGA) and can be similar to another tick-borne disease, ehrlichiosis. However, these are distinct diseases that are transmitted by different ticks.