Archive for the ‘CDC’ Category

CDC adds new destinations to the Zika virus travel alerts: Barbados, Bolivia, Ecuador, Guadeloupe, Saint Martin, Guyana, Cape Verde, and Samoa.

Saturday, January 23rd, 2016CDC adds countries to interim travel guidance related to Zika virus

As more information becomes available, CDC travel alerts will be updated. Travelers to areas where cases of Zika virus infection have been recently confirmed are at risk of being infected with the Zika virus. Travelers to these areas may also be at risk of being infected with dengue or chikungunya viruses. Mosquitoes that spread Zika, chikungunya, and dengue are aggressive daytime biters, prefer to bite people, and live indoors and outdoors near people. There is no vaccine or medicine available for Zika virus. The best way to avoid Zika virus infection is to prevent mosquito bites.

Some travelers to areas with ongoing Zika virus transmission will become infected while traveling but will not become sick until they return home. Symptoms include fever, rash, joint pain, and red eyes. Other commonly reported symptoms include muscle pain, headache, and pain behind the eyes. The illness is usually mild with symptoms lasting from several days to a week. Severe disease requiring hospitalization is uncommon and case fatality is low. Travelers to these areas should monitor for symptoms or illness upon return. If they become ill, they should tell their healthcare professional where they have traveled and when.

Until more is known, and out of an abundance of caution, CDC continues to recommend that pregnant women and women trying to become pregnant take the following precautions:

- Pregnant women in any trimester should consider postponing travel to the areas where Zika virus transmission is ongoing. Pregnant women who must travel to one of these areas should talk to their doctor or other healthcare professional first and strictly follow steps to avoid mosquito bites during the trip.

- Women trying to become pregnant should consult with their healthcare professional before traveling to these areas and strictly follow steps to prevent mosquito bites during the trip.

Guillain-Barré syndrome (GBS) has been reported in patients with probable Zika virus infection in French Polynesia and Brazil. Research efforts will also examine the link between Zika and GBS.

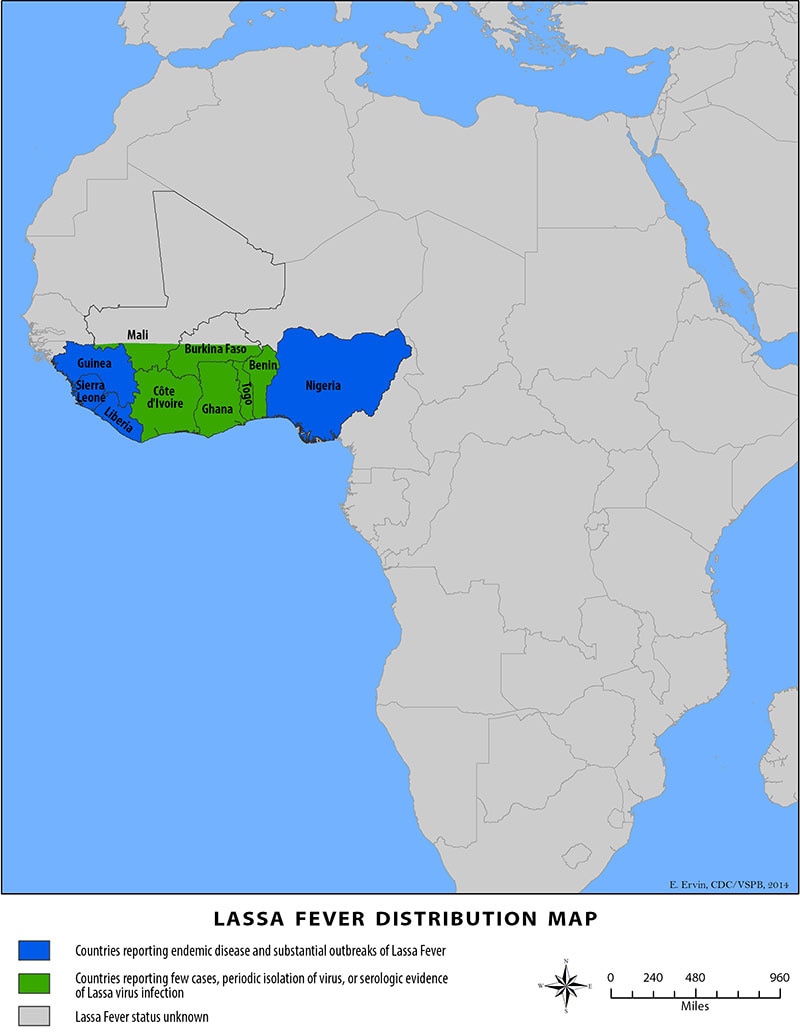

** Nigeria: Lassa Fever has claimed 63 lives out of 212 suspected cases reported from 62 local government areas in affected states.

Saturday, January 23rd, 2016

“…The reservoir, or host, of Lassa virus is a rodent known as the “multimammate rat” (Mastomys natalensis). Once infected, this rodent is able to excrete virus in urine for an extended time period, maybe for the rest of its life. Mastomys rodents breed frequently, produce large numbers of offspring, and are numerous in the savannas and forests of west, central, and east Africa. In addition, Mastomys readily colonize human homes and areas where food is stored. All of these factors contribute to the relatively efficient spread of Lassa virus from infected rodents to humans.

Transmission of Lassa virus to humans occurs most commonly through ingestion or inhalation. Mastomys rodents shed the virus in urine and droppings and direct contact with these materials, through touching soiled objects, eating contaminated food, or exposure to open cuts or sores, can lead to infection……..

Signs and symptoms of Lassa fever typically occur 1-3 weeks after the patient comes into contact with the virus. For the majority of Lassa fever virus infections (approximately 80%), symptoms are mild and are undiagnosed. Mild symptoms include slight fever, general malaise and weakness, and headache. In 20% of infected individuals, however, disease may progress to more serious symptoms including hemorrhaging (in gums, eyes, or nose, as examples), respiratory distress, repeated vomiting, facial swelling, pain in the chest, back, and abdomen, and shock. Neurological problems have also been described, including hearing loss, tremors, and encephalitis. Death may occur within two weeks after symptom onset due to multi-organ failure.

The most common complication of Lassa fever is deafness. Various degrees of deafness occur in approximately one-third of infections, and in many cases hearing loss is permanent. As far as is known, severity of the disease does not affect this complication: deafness may develop in mild as well as in severe cases.

Approximately 15%-20% of patients hospitalized for Lassa fever die from the illness. However, only 1% of all Lassa virus infections result in death. The death rates for women in the third trimester of pregnancy are particularly high. Spontaneous abortion is a serious complication of infection with an estimated 95% mortality in fetuses of infected pregnant mothers.

Because the symptoms of Lassa fever are so varied and nonspecific, clinical diagnosis is often difficult. Lassa fever is also associated with occasional epidemics, during which the case-fatality rate can reach 50% in hospitalized patients….”

CDC HEALTH ADVISORY on Zika virus, travel, and pregnant women

Saturday, January 16th, 2016Recognizing, Managing, and Reporting Zika Virus Infections in Travelers Returning from Central America, South America, the Caribbean, and Mexico

This is an official

CDC HEALTH ADVISORY

Distributed via the CDC Health Alert Network

Friday, January 15, 2016, 19:45 EST (7:45 PM EST)

CDCHAN-00385

Summary

In May 2015, the World Health Organization reported the first local transmission of Zika virus in the Western Hemisphere, with autochthonous (locally acquired) cases identified in Brazil. As of January 15, 2016, local transmission had been identified in at least 14 countries or territories in the Americas, including Puerto Rico (See Pan American Health Organization [PAHO] link below for countries and territories in the Americas with Zika virus transmission). Further spread to other countries in the region is likely.

Local transmission of Zika virus has not been documented in the continental United States. However, Zika virus infections have been reported in travelers returning to the United States. With the recent outbreaks in the Americas, the number of Zika virus disease cases among travelers visiting or returning to the United States likely will increase. These imported cases may result in local spread of the virus in some areas of the continental United States, meaning these imported cases may result in human-to-mosquito-to-human spread of the virus.

Zika virus infection should be considered in patients with acute onset of fever, maculopapular rash, arthralgia or conjunctivitis, who traveled to areas with ongoing transmission in the two weeks prior to illness onset. Clinical disease usually is mild. However, during the current outbreak, Zika virus infections have been confirmed in several infants with microcephaly and in fetal losses in women infected during pregnancy. We do not yet understand the full spectrum of outcomes that might be associated with infection during pregnancy, nor the factors that might increase risk to the fetus. Additional studies are planned to learn more about the risks of Zika virus infection during pregnancy.

Healthcare providers are encouraged to report suspected Zika virus disease cases to their state health department to facilitate diagnosis and to mitigate the risk of local transmission. State health departments are requested to report laboratory-confirmed cases to CDC. CDC is working with states to expand Zika virus laboratory testing capacity, using existing RT-PCR protocols.

This CDC Health Advisory includes information and recommendations about Zika virus clinical disease, diagnosis, and prevention, and provides travel guidance for pregnant women and women who are trying to become pregnant.

Until more is known and out of an abundance of caution, pregnant women should consider postponing travel to any area where Zika virus transmission is ongoing.

Pregnant women who do travel to these areas should talk to their doctors or other healthcare providers first and strictly follow steps to avoid mosquito bites during the trip. Women trying to become pregnant should consult with their healthcare providers before traveling to these areas and strictly follow steps to avoid mosquito bites during the trip.

Background

Zika virus is a mosquito-borne flavivirus transmitted primarily by Aedes aegypti. Aedes albopictus mosquitoes might also transmit the virus. Outbreaks of Zika virus disease have been reported previously in Africa, Asia, and islands in the Pacific.

Clinical Disease

About one in five people infected with Zika virus become symptomatic. Characteristic clinical findings include acute onset of fever, maculopapular rash, arthralgia, or conjunctivitis. Clinical illness usually is mild with symptoms lasting for several days to a week. Severe disease requiring hospitalization is uncommon and fatalities are rare. During the current outbreak in Brazil, Zika virus RNA has been identified in tissues from several infants with microcephaly and from fetal losses in women infected during pregnancy. The Brazil Ministry of Health has reported a marked increase in the number of babies born with microcephaly. However, it is not known how many of the microcephaly cases are associated with Zika virus infection and what factors increase risk to the fetus. Guillain-Barré syndrome also has been reported in patients following suspected Zika virus infection.

Diagnosis

Zika virus infection should be considered in patients with acute onset of fever, maculopapular rash, arthralgia, or conjunctivitis who recently returned from affected areas. To confirm evidence of Zika virus infection, RT-PCR should be performed on serum specimens collected within the first week of illness. Immunoglobulin M and neutralizing antibody testing should be performed on specimens collected ≥4 days after onset of illness. Zika virus IgM antibody assays can be positive due to antibodies against related flaviviruses (e.g., dengue and yellow fever viruses). Virus-specific neutralization testing provides added specificity but might not discriminate between cross-reacting antibodies in people who have been previously infected with or vaccinated against a related flavivirus.

There is no commercially available test for Zika virus. Zika virus testing is performed at the CDC Arbovirus Diagnostic Laboratory and a few state health departments. CDC is working to expand laboratory diagnostic testing in states, using existing RT-PCR protocols. Healthcare providers should contact their state or local health department to facilitate testing.

Treatment

No specific antiviral treatment is available for Zika virus disease. Treatment is generally supportive and can include rest, fluids, and use of analgesics and antipyretics. Because of similar geographic distribution and symptoms, patients with suspected Zika virus infections also should be evaluated and managed for possible dengue or chikungunya virus infection. Aspirin and other non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) should be avoided until dengue can be ruled out to reduce the risk of hemorrhage. In particular, pregnant women who have a fever should be treated with acetaminophen. People infected with Zika, chikungunya, or dengue virus should be protected from further mosquito exposure during the first few days of illness to reduce the risk of local transmission.

Prevention

No vaccine or preventive drug is available. The best way to prevent Zika virus infection is to:

- Avoid mosquito bites.

- Use air conditioning or window and door screens when indoors.

- Wear long sleeves and pants, and use insect repellents when outdoors. Most repellents, including DEET, can be used on children older than two months. Pregnant and lactating women can use all Environmental Protection Agency (EPA)-registered insect repellents, including DEET, according to the product label.

Recommendations for Health Care Providers and Public Health Practitioners

- Zika virus infection should be considered in patients with acute fever, rash, arthralgia, or conjunctivitis, who traveled to areas with ongoing transmission in the two weeks prior to onset of illness.

- All travelers should take steps to avoid mosquito bites to prevent Zika virus infection and other mosquito-borne diseases.

- Until more is known and out of an abundance of caution, pregnant women should consider postponing travel to any area where Zika virus transmission is ongoing. Pregnant women who do travel to one of these areas should talk to their doctors or other healthcare providers first and strictly follow steps to avoid mosquito bites during the trip. Women trying to become pregnant should consult with their healthcare providers before traveling to these areas and strictly follow steps to avoid mosquito bites during the trip.

- Fetuses and infants of women infected with Zika virus during pregnancy should be evaluated for possible congenital infection and neurologic abnormalities.

- Healthcare providers are encouraged to report suspected Zika virus disease cases to their state or local health department to facilitate diagnosis and to mitigate the risk of local transmission.

- Health departments should perform surveillance for Zika virus disease in returning travelers and be aware of the risk of possible local transmission in areas where Aedes species mosquitoes are active.

- State health departments are requested to report laboratory-confirmed Zika virus infections to CDC.

For More Information

- General information about Zika virus and disease: http://www.cdc.gov/zika/

- Zika virus information for clinicians: http://www.cdc.gov/zika/hc-providers/index.html

- Protection against mosquitoes: http://wwwnc.cdc.gov/travel/yellowbook/2016/the-pre-travel-consultation/protection-against-mosquitoes-ticks-other-arthropods

- Travel notices related to Zika virus: http://wwwnc.cdc.gov/travel/notices

- Information about Zika virus for travelers and travel health providers: http://wwwnc.cdc.gov/travel/yellowbook/2016/infectious-diseases-related-to-travel/zika

- Pan American Health Organization (PAHO): http://www.cdc.gov/ncbddd/birthdefects/microcephaly.html

- Approximate distribution of Aedes aegypti and Ae. albopictus mosquitoes in the United States: http://www.cdc.gov/chikungunya/resources/vector-control.html

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) protects people’s health and safety by preventing and controlling diseases and injuries; enhances health decisions by providing credible information on critical health issues; and promotes healthy living through strong partnerships with local, national and international organizations.

Department of Health and Human Services

CDC: Motor vehicle crashes are the #1 killer of healthy US citizens in foreign countries.

Wednesday, January 13th, 2016CDC: International Road Safety

Follow these tips to minimize your risk of being injured in a car crash while you’re on vacation.

Most people think about travel vaccines when they’re planning an international trip, but few people consider the possibility that they might be involved in a car crash. Motor vehicle crashes are the leading cause of death among healthy travelers, and no vaccine can prevent a car wreck. Fortunately, a little bit of knowledge and awareness can go a long way toward keeping you safe.

Just the Stats

Each year, 1.3 million people are killed and 20–50 million are injured in motor vehicle crashes worldwide. Most (85%) of these casualties occur in low- or middle-income countries, and 25,000 of the deaths are among tourists. Nearly half of medical evacuations back to the United States are the result of a car crash, and a medical evacuation can cost upward of $100,000.

Why Are Car Crashes a Risk for Travelers?

More and more people are driving cars and riding motorcycles in developing countries, and these countries are an increasingly common destination for US tourists. Roads in these countries may be poorly maintained, and traffic laws may be haphazardly followed or enforced. A crash in a developing country is more likely to be fatal because emergency care may not be readily available. It may take a long time to get to a center that can provide appropriate care, and care, where available, may not be up to US standards.

Tourists may get behind the wheel in a foreign country without being adequately informed of local traffic laws, they may not be accustomed to driving on the left, or they may be driving vehicles (such as rented motorcycles or scooters) that they do not know how to properly operate. In addition, the excitement of being on vacation may encourage travelers to engage in risky behaviors, such as drinking and driving, that they would never do at home.

What Can I Do to Avoid a Crash?

Take the following steps to minimize your risk of being injured in a crash while you’re on vacation:

- Always wear seatbelts and put children in car seats.

- When possible, avoid riding in a car in a developing country at night.

- Don’t ride motorcycles. If you must ride a motorcycle, wear a helmet.

- Know local traffic laws before you get behind the wheel.

- Don’t drink and drive.

- Ride only in marked taxis that have seatbelts.

- Avoid overcrowded, overweight, or top-heavy buses or vans.

- Be alert when crossing the street, especially in countries where people drive on the left.

Following these tips is the best way you can keep from getting in a motor vehicle crash and ensure a safe and healthy vacation. (But don’t forget your travel vaccines, either!)

More Information

- Global Road Safety

- Motor Vehicle Safety

- The Association for Safe International Road Travel

- Make Roads Safe: The Campaign for Global Road Safety

- CDC Travelers’ Health

- Injuries and Safety from CDC Health Information for International Travel 2012 (Yellow Book)

Weekly U.S. Influenza Surveillance Report: 2015-2016 Influenza Season Week 52 ending January 2, 2016

Monday, January 11th, 2016Synopsis:

During week 52 (December 26, 2015-January 2, 2016), influenza activity increased slightly in the United States.

- Viral Surveillance: The most frequently identified influenza virus type reported by public health laboratories during week 52 was influenza A, with influenza A (H1N1)pdm09 viruses predominating. The percentage of respiratory specimens testing positive for influenza in clinical laboratories was low.

- Novel Influenza A Virus: One human infection with a novel influenza A virus was reported.

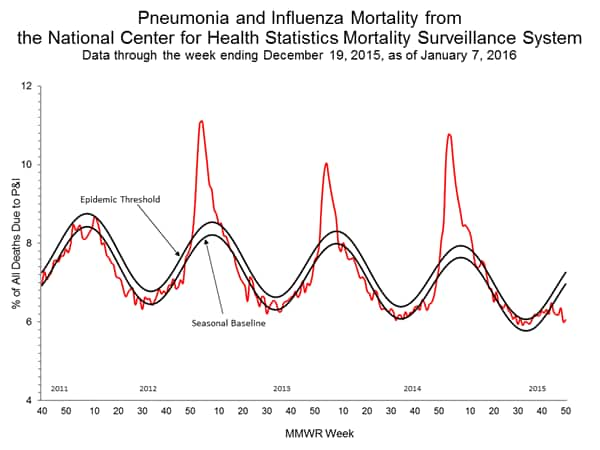

- Pneumonia and Influenza Mortality: The proportion of deaths attributed to pneumonia and influenza (P&I) was below their system-specific epidemic threshold in both the NCHS Mortality Surveillance System and the 122 Cities Mortality Reporting System.

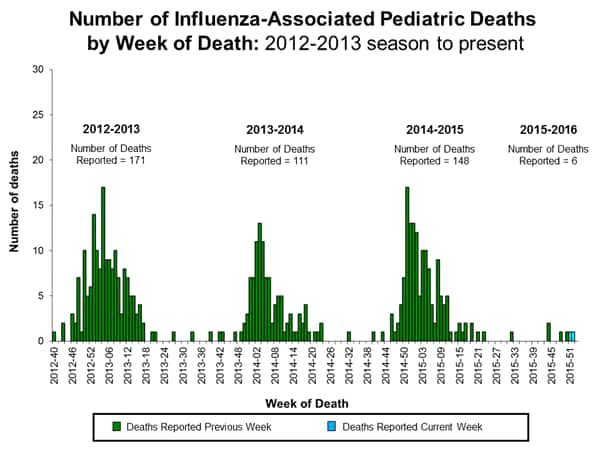

- Influenza-associated Pediatric Deaths: Two influenza-associated pediatric deaths were reported.

<!–

- Influenza-associated Hospitalizations: A cumulative rate for the season of 65.5 laboratory-confirmed influenza-associated hospitalizations per 100,000 population was reported.

–>

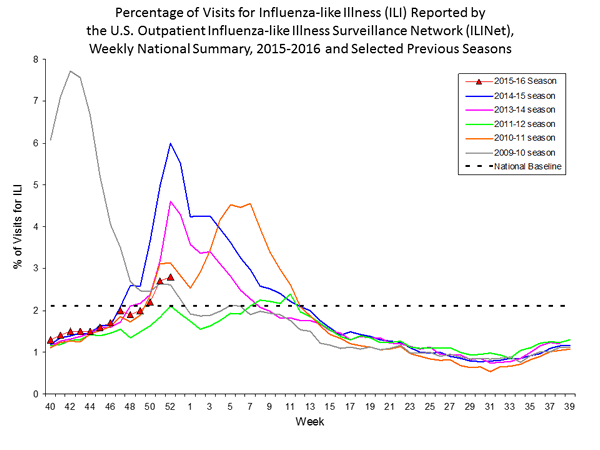

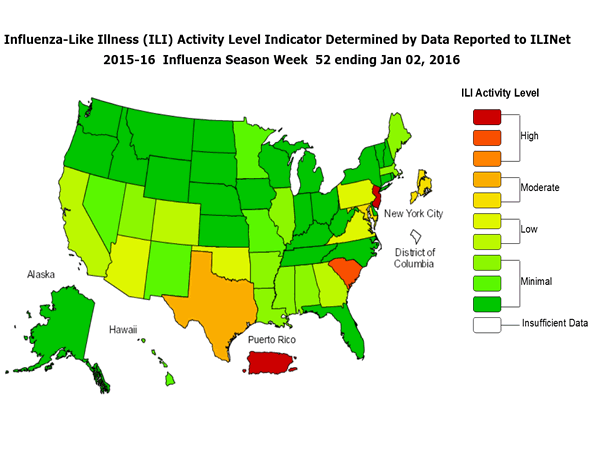

- Outpatient Illness Surveillance: The proportion of outpatient visits for influenza-like illness (ILI) was 2.8%, which is above the national baseline of 2.1%. Seven of 10 regions reported ILI at or above region-specific baseline levels. Puerto Rico and two states experienced high ILI activity; New York City and two states experienced moderate ILI activity; seven states experienced low ILI activity; 39 states experienced minimal ILI activity; and the District of Columbia had insufficient data.

- Geographic Spread of Influenza: The geographic spread of influenza in Guam and two states were reported as widespread; six states reported regional activity; 13 states reported local activity; the U.S. Virgin Islands and 27 states reported sporadic activity; the District of Columbia and two states reported no influenza activity; and Puerto Rico did not report.

Global Disease Detection: Advancing the Science of Global Public Health

Thursday, December 31st, 2015Did You Know

Three of the top 10 causes of death globally are from infectious diseases? 1

Most of these deaths are occurring in low- and middle-income countries? 2

About 2/3 of the world’s countries remain unprepared to prevent, detect, and respond to infectious disease threats? 3

How We Help

CDC’s Global Disease Detection program rapidly detects, accurately identifies, and promptly contains emerging infectious diseases and bioterrorist threats to promote global health security. We track outbreaks and deploy staff through the Global Disease Detection Operations Center.

Where We Are

Bangladesh, Central America (Guatemala), Central Asia (Kazakhstan), China, Egypt, India, Kenya, South Africa, South Caucasus (country of Georgia), and Thailand.

By the Numbers

Ten GDD Centers have extended support to nearly 50 countries

Discovered 12 pathogens new to the world

75M+ people under surveillance for key infectious diseases and syndromes

30-40 GDD Operations Center monitors 30 – 40 public health threats daily

Who We Are

- Health Scientists

- Public Health Advisors

- Laboratorians

- Field Epidemiologists

- Medical Officers

- Health Communicators

How We Do It

Outbreak Response:

- Respond to disease outbreaks and other public health emergencies

Impact

- Responded to 1,700 disease outbreaks

- Nearly 2/3 of outbreaks responded to within 24 hours

- Comprehensive response: 85% of outbreaks that involved lab support were given a confirmed cause

Pathogen Discovery:

- Identify disease threats before they spread

- Conduct innovative research into the epidemiology and biology of emerging infections

Impact

- Discovered 12 pathogens new to the world

- Increased capacity to identify pathogens, through 289 diagnostic tests, leading to faster response times worldwide

Training:

- Build a global health workforce

- Improve the quality of epidemiology and laboratory science

Impact

- Trained ~100K participants on epidemiology, laboratory, all hazards preparedness, risk communication and other topics

Surveillance:

- Strengthen systems to detect, assess, and monitor infectious disease threats

Impact:

- Over 75 million people under surveillance for key infectious diseases and syndromes

- Data is used to detect outbreaks, make policy recommendations, evaluate interventions, and measure public health impact

Build network capacity:

- Enhance collaboration through shared resources and cooperation

Impact

With WHO and local ministries of health:

- Worked to control the spread of infections, including antibiotic resistance, in healthcare settings

With WHO and other partners:

- Assessed countries’ ability to meet International Health Regulations (IHR)

Cumulative data from 2006 – 2014

“The U.S. and the world are at a greater risk today than ever before from biological organisms. In today’s globalized world, an outbreak anywhere is a threat everywhere.”

– CDC Director Tom Frieden, MD, MPH

To learn more: http://www.cdc.gov/globalhealth/healthprotection/gdd/index.html

CDC- Ebola Response: Year in Review

Sunday, December 20th, 2015Ebola Response: Year in Review

Posted on December 14, 2015 by

Throughout the month of December, Public Health Matters is conducting a series of year-in-review posts of some of the most impactful disease outbreaks of 2015. These posts will give you a glimpse of the work CDC is doing to prevent, identify, and respond to public health threats.

Getting to Zero

Getting to Zero was a theme and goal that dominated much of CDC’s attention in 2015. In January 2015, The World Health Organization reported that the Ebola epidemic had reached a turning point with the most impacted countries, Liberia, Guinea and Sierra Leone, seeing declines in the number of new cases of Ebola. This turning point came after a year of battling the worst Ebola outbreak in history—resulting in over 20,000 cases by December 2014.

While the spread of the disease and U.S. media attention was at its peak in 2014, some of CDC’s most impactful and important work took place in 2015. This year’s response to the Ebola epidemic was marked with many challenges and accomplishments, new discoveries, and continuous hard work by hundreds of CDC staff. The dedication of CDC and its partners throughout the year has also led to the successful end of widespread Ebola transmission in Liberia and Sierra Leone.

Ebola Vaccine Trials

In April 2015, CDC, in partnership with The College of Medicine and Allied Health Sciences, University of Sierra Leone, and the Sierra Leone Ministry of Health and Sanitation, began a clinical trial to test the potential of a new vaccine to protect against the Ebola virus. This vaccine trial, known as Sierra Leone Trial to Introduce a Vaccine against Ebola (STRIVE), is designed to help protect against Zaire ebolavirus, the virus that is causing the current outbreak in West Africa.

“A safe and effective vaccine would be a very important tool to stop Ebola in the future, and the front-line workers who are volunteering to participate are making a decision that could benefit health care professionals and communities wherever Ebola is a risk,” said CDC Director Tom Frieden, M.D., M.P.H. “We hope this vaccine will be proven effective but in the meantime we must continue doing everything necessary to stop this epidemic —find every case, isolate and treat, safely and respectfully bury the dead, and find every single contact.”

“A safe and effective vaccine would be a very important tool to stop Ebola in the future, and the front-line workers who are volunteering to participate are making a decision that could benefit health care professionals and communities wherever Ebola is a risk,” said CDC Director Tom Frieden, M.D., M.P.H. “We hope this vaccine will be proven effective but in the meantime we must continue doing everything necessary to stop this epidemic —find every case, isolate and treat, safely and respectfully bury the dead, and find every single contact.”

This vaccine trial, along with a series of other vaccine trials taking place in West Africa, represents an important step in the response to the Ebola epidemic. In addition to the tireless efforts being made to completely eliminate Ebola cases, efforts to discover a vaccine could prevent an outbreak of this size in the future.

Leaving Lasting Infrastructures for Health

Programs like STRIVE seek to contribute not only to the future of Ebola prevention research, but also to the future of health care capabilities in the areas impacted by the Ebola epidemic. The STRIVE study is strengthening the existing research capacity of institutions in Sierra Leone by providing training and research experience to hundreds of staff to use now and for future studies.

CDC is leaving behind newly created emergency operation centers (EOC) in countries affected by widespread Ebola outbreaks. The ministries of health will fully lead these new EOCs, which will provide a place to train healthcare workers to be better prepared to conduct outbreak surveillance and response.

Additionally, 2015 brought the official announcement of plans to create the African Centres for Disease Control and Prevention (African CDC). First proposed in 2013, the African CDC will seek ongoing collaboration with other public health entities across the continent and the world to elevate health outcomes for all citizens. Partners will assist by implementing activities, supporting the establishment of regional collaborating centers, advising the African CDC leadership and staff, and providing technical assistance.

Celebrate the Successes, Look to the Future

2015 brought significant progress in the Ebola response. Yet, while the successes and improvements made to public health infrastructure in West Africa are important to celebrate, the work continues to get to zero and end the largest Ebola outbreak in history.

As we draw closer to our goal of zero cases of Ebola, we are reminded of how critical it is to identify, prevent, and respond to outbreaks to prevent future epidemics of this magnitude.

Posted on December 14, 2015 by

CDC: Zoonotic Diseases in South Africa

Friday, December 18th, 2015Global Disease Detection Stories: Tracking and Taming Zoonotic Diseases in South Africa

A One Health program in South Africa connects physicians and veterinarians to better understand causes of human disease by looking at animals in a new light.

Collecting samples from African buffalo in Kruger National Park.

How do you tonsil swab a wild African buffalo? More importantly, why? The answer is that buffaloes are reservoirs for certain “zoonotic” diseases, or diseases that can be passed from animals to humans. Many infectious diseases (such as rabies and Rift Valley Fever) are transmitted through animals, which is why tracking animal diseases that could potentially jump to humans is a crucial aspect of public health. Early detection means spotting these diseases in animals before they make people sick.

Tracking disease in a national park

Dr. Marietjie Venter of the Global Disease Detection program in South Africa, visited Kruger National Park along with Jumari Steyn, a PhD student from the University of Pretoria. As part of a wildlife surveillance program, a skilled group of veterinarians sampled 30 buffalo in three hours. They swabbed tonsils and collected blood, fecal, and stomach content to investigate foot and mouth disease (FMD), which can cause major outbreaks in cattle if they come into contact with infected buffalo.

“Early detection means spotting diseases in animals before they make people sick.”

While buffalo are natural reservoirs for FMD, they are also thought to carry Rift Valley Fever, bovine tuberculosis, and other bacteria and viruses that could potentially spread to humans. The University’s research unit will use the collected samples to investigate for these zoonotic diseases which have been detected in wildlife, farm animals and humans.

An expanded partnership between the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) South Africa and the University’s research unit improves surveillance capacity to include priority zoonotic diseases in the region: anthrax, brucellosis, rodent- and bat-borne pathogens, and many others. It also adds additional data collection sites and enhances reporting.

Bridging animal health and human health

Tracking diseases in domestic animals and wildlife has been happening for a long time, but linking that information to humans who are sick or could become sick has not. South Africa has strong surveillance systems; CDC’s role has been to support and expand them through its One Health program.

Buffalo are natural reservoirs for foot and mouth disease.

While it makes sense to get human and animal experts together, this is not an easy task. The One Health initiative has programs all over the world and builds bridges between people who may not otherwise work together. The success of the program lies in the regularity of the exchanges. One Health programs explores connections between human health, animal health, and the environment, bringing together experts in fields as diverse as climate change, farming practices, and wildlife management. According to Dr. Wanda Markotter, the Principal Investigator for CDC’s original agreement with the University of Pretoria, “This new project will significantly enhance the collaboration between the Health and Veterinary faculties to develop joint surveillance and diagnostic programs on zoonotic disease in South Africa and provide feedback to the Ministries of Health and Agriculture in South Africa.”

So back to that buffalo. Are you curious about how those specimens are collected?

Step 1: Tranquilizer dart.

Step 2: Apply blindfold.

Step 3: Drag with tractor to recovery area.

Step 4: Collect sample.

Step 5: Provide tranquilizer antidote.

Step 6: Run! Doctors treating humans may want to count their blessings.

A cooperative agreement between CDC and the University of Pretoria’s Zoonoses Research Unit is expanding zoonotic disease surveillance in South Africa. This work is coordinated through the GDD Center in South Africa, which is part of CDC’s country office.

CDC: In India, acute diarrheal diseases and food poisoning routinely account for over 40% of infectious disease outbreaks.

Friday, December 18th, 2015Global Disease Detection Stories: Coordinated Outbreak Response Puts Diarrhea on the Run

Globally, there are nearly 1.7 billion cases of diarrheal disease every year.

In India, the problem is widespread: acute diarrheal diseases and food poisoning routinely account for over 40% of infectious disease outbreaks.

An India EIS officer helps the district rapid response team take interviews after a food poisoning outbreak in Gujarat. Photo courtesy of Mayank Dwivedi.

People think of their wedding day as the happiest day of their lives. In India, weddings often include several days of festivities with friends and family. Symptoms like “abdominal pain,” and “vomiting” are unwanted guests, but they crashed one wedding party in Gujarat State.

Fortunately, India is committed to strengthening outbreak response and surveillance for acute diarrheal and foodborne diseases. Within 24 hours, four people were deployed to conduct an investigation to find the cause of the wedding outbreak. Two investigators were Indian EIS Officers and two were from the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Combining forces, they surveyed households to track down nearly 400 wedding guests from four villages to identify potential cases and get more information about foods the sick guests ate. Ninety-two people reported symptoms and eight were hospitalized.

Spoiled milk

The culprit? The team traced the likely source of the outbreak to basundi, a dessert made of condensed milk topped with dry fruit and served cold. The officers discovered there was a 10-hour power outage two days before the wedding that affected the dairy where the milk was purchased.

Practice makes perfect

Laboratorian receives training through the Global Acute Diarrheal Disease pilot project.

Solving foodborne outbreaks is not easy. It takes training, patience, practice, and many partners. Thanks to a longstanding scientific collaboration known as the Global Foodborne Infections Network, countries, including India, are getting the tools and relationships they need to solve outbreaks. Epidemiologists, microbiologists, lab technicians, and healthcare staff are trained and mentored on procedures for stool specimen collection, transport, laboratory testing, and reporting.

The key to cracking foodborne outbreaks is testing stool specimens from sick people. In two years, as part of a pilot project, over 30 outbreaks have been detected and reported in four districts; 2000 samples have been properly collected, transported, and tested. Clinical specimens were tested in 75% of those outbreaks—results that are on par with the best standards in the world.

Plans are being discussed to double the number of districts and add activities. With better ability to track, test for, and prevent foodborne illnesses, gatherings all over India could turn away uninvited bacterial guests.

Progress in tracking and responding to acute diarrheal disease and outbreaks in India is thanks to the Global Acute Diarrheal Disease Pilot Project in partnership with CDC’s Division of Foodborne, Waterborne, and Environmental Disease, The Global Foodborne Infections Network, and India’s National Centre for Disease Control’s Integrated Disease Surveillance Program. This work is coordinated through the GDD Center in India, which is part of CDC’s country office. India is one of 30 U.S. partner countries named in the Global Health Security Agenda.

CDC: Eliminating Hepatitis C in the Country of Georgia

Friday, December 18th, 2015Global Disease Detection Stories: Going Above and Beyond to Eliminate Hepatitis C in the Country of Georgia

Georgia is the first country to take on the challenge of completely eliminating Hepatitis C (HCV) – a serious viral infection – and they’re using a team of international disease detectives to find out how it’s spreading.

To stop a disease in its tracks, you need to get ahead of it. Sometimes this means going off the beaten path, into remote villages where your GPS doesn’t work, into people’s homes and businesses. Sometimes the people there speak your language, sometimes they don’t. But when the disease you’re tracking doesn’t know any boundaries, neither can you.

In the country of Georgia, the culprit is Hepatitis C (HCV). HCV is a serious viral infection that, over time, can cause liver damage and even liver cancer. Almost 7% of Georgia’s population is affected by this disease — the third highest rate in the world. As part of an ongoing collaboration, epidemiologist Dr. Stephanie Salyer, who is based at the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) in Atlanta, and her team have been in the field conducting a door-to-door survey to find out how HCV is spreading.

A unique set of challenges

Particularly in the country of Georgia, language barriers can present a challenge. In some areas, Georgian citizens speak Armenian and Azerbaijani languages, but little to no Georgian. To address this, a diverse group of 45 field staff from Georgia’s National Center for Disease Control (NCDC), joined by Field Epidemiology Training Program residents from Georgia, Armenia and Azerbaijan, were selected and trained to conduct the survey.

Each team surveyed 25 households per day, which is harder than it sounds. Teams used GPS units and Google maps to locate homes to survey, but, particularly in rural areas, navigation proved challenging. More than once, teams – which included interviewers, nurses, and drivers — ended up hiking in the middle of nowhere past abandoned houses. The teams worked long hours and became “like a family,” said Salyer.

Perhaps the most difficult challenge was “hearing heartbreaking stories from people in the field with Hepatitis C. A lot of team members personally knew people impacted by this disease. That is why we were so invested in this project. This really highlights the tragedy of Hepatitis C in Georgia: it has touched almost everybody in the country,” said Salyer.

Putting data to work

Teams in the field used smart phone technology to enter the survey responses, automatically uploading the data into the cloud. Survey participants benefited by learning their HCV status, receiving health education materials in their preferred language, and getting their BMI and blood pressure measured. Public health nurses on the survey teams referred participants to local health care facilities and national information hotlines if needed.

Survey results are already informing national strategy. Experts assumed that HCV in Georgia could be traced back to intravenous drug use, reusing syringes, or being previously incarcerated. New information may indicate that transmission could also be associated with lack of infection control surrounding medical and dental procedures, and even tattoo parlors and manicure salons. Data is making researchers look in a new direction.

A strong commitment

The team locates survey households in Georgia. Georgia’s survey teams really went above and beyond.

The results from this survey will inform where to target prevention messages and who can benefit from treatment and screening. A remarkable public-private partnership with pharmaceutical manufacturer Gilead Sciences is supporting the program by providing 5,000 courses of the medication Sovaldi for the initial phase, followed by 20,000 courses of Harvoni free annually.

Several factors make HCV elimination a possibility in Georgia: the availability of effective diagnostics and treatment; the country’s small size and population; experience with HIV prevention and control programs; and strong political will and public support. Despite this, limitations exist in Georgia’s ability to track cases, reduce transmission, and provide care and treatment. Most infected people remain untested and unaware of their infection.

The principal investigator and one of the team’s phlebotomists even appeared on a local talk show to educate the public about Hepatitis C and encourage survey participation in cities.

Salyer recalls the commitment of the survey teams: “They went above and beyond. I would have to force them to come back at the end of the day.”

Progress in eliminating HCV in Georgia is a product of strong collaboration with the U.S. CDC’s Division of Viral Hepatitis in Atlanta and Georgia’s National Center for Disease Control. This work is coordinated through the GDD Regional Center for Georgia and the South Caucasus, which is part of CDC’s country office. Georgia is one of 30 U.S. partner countries named in the Global Health Security Agenda.