Archive for the ‘CDC’ Category

CDC video on Candida auris-2019

Tuesday, August 6th, 2019

Candida auris (C. auris) is an emerging fungus that presents a serious global health threat. CDC is concerned about C. auris for 3 main reasons:

- It is often multidrug-resistant, meaning multiple antifungal drugs are less or not at all effective in treating C. auris.

- It is difficult to identify with standard laboratory methods, and it can be misidentified in labs without specific technology. Misidentification may lead to inappropriate management.

- It has caused outbreaks in healthcare settings. It is important to quickly identify C. auris in a hospitalized patient so that healthcare facilities can take special precautions to stop its spread.

Most C. auris cases in the United States have been detected in the New York City area, New Jersey, and the Chicago area. Clusters of cases have also recently been described in Florida, Texas, and California. C. auris cases in the United States are originally a result of inadvertent introduction into the United States from a patient who had received healthcare in a country where C. auris has been reported. Most cases now are a result of local spread after such an introduction.

CDC: Personal provisions, supplies, and equipment necessary to protect the health and safety of your family in an emergency.

Tuesday, April 9th, 2019The Basics

- Water

- Store at least 1 gallon of water per day for each person and each pet. You should consider storing more water than this for hot climates, for pregnant women, and for persons who are sick.

- Store at least a 3-day supply of water for each person and each pet. Try to store a 2-week supply, if possible.

- Observe the expiration date for store-bought water. Replace non-store bought water every 6 months.

- Store a bottle of unscented liquid household chlorine bleach (label should say it contains between 5-6% and 8.25% of sodium hypochlorite) to disinfect your water, if necessary, and to use for general cleaning and sanitizing.

- Nonperishable and ready-to-eat food, including special foods—such as nutrition drinks and ready-to-feed formula—for infants, people with dietary restrictions, food sensitivities and allergies, and medical conditions such as diabetes.

- Prescription eyeglasses, contact lenses, and contact lens solution.

- Assistive technologies, such as hearing aids and picture boards.

- Medical alert identification bracelet or necklace

- Health protection supplies, including insect repellentExternal, water purification tablets, and sunscreen.

- A change of clothes

- Medical equipment including:

- Canes, crutches, walkers, and wheelchairs

- Nebulizers

- Oxygen equipment

- Blood sugar monitors

- Medical supplies, including:

- Antibacterial wipes

- Catheters

- Syringes

- Nasal cannulas

- Blood test strips

- First aid supplies, including:

- First aid reference

- Non-latex gloves

- Digital thermometer

- Waterproof bandages and gauze

- Tweezers and scissors

- A Stop the Bleed kit, including a tourniquet

- Sanitation and hygiene items, including:

- Soap

- Hand sanitizer

- Sanitizing wipes

- Garbage bags and plastic ties

- Toilet paper

- Feminine hygiene supplies

- Pet supplies

- Childcare supplies

- Baby supplies

CDC: How to prepare for and respond to a smallpox emergency with smallpox vaccination how-to videos.

Monday, February 25th, 2019

Where will the US public go for antivirals in a pandemic?

Friday, January 25th, 2019CDC: Prepare Your Vehicle for Winter Weather

Wednesday, December 19th, 2018

Prepare for extremely cold weather every winter—it’s always a possibility. You can avoid many dangerous winter travel problems by planning ahead.

There are steps you can take in advance for greater wintertime safety in your car.

Have maintenance service on your vehicle as often as the manufacturer recommends. In addition, every fall, do the following:

- Have the radiator system serviced or check the antifreeze level yourself with an antifreeze tester. Add antifreeze as needed.

- Replace windshield-wiper fluid with a wintertime mixture.

- Replace any worn tires, make sure the tires have adequate tread, and check the air pressure in the tires.

During winter, keep the gas tank near full to help avoid ice in the tank and fuel lines.

Checklist

Keep your car fueled and in good working order. Be sure to check the following:

- Antifreeze

- Windshield wiper fluid (wintertime mixture)

- Heater

- Defroster

- Brakes

- Brake fluid

- Ignition

- Emergency flashers

- Exhaust

- Tires (air pressure and wear)

- Fuel

- Oil

- Battery

- Radiator

Summary of Process for Emergency Use Authorization (EUA) Issuance

Thursday, December 6th, 2018The flow chart below provides a summary of the process for Emergency Use Authorization (EUA) issuance.

Description of chart:

Issuance of an EUA by the FDA Commissioner requires several steps under section 564 of the FD&C Act. First, one of the four following determinations must be in place:

- The Department of Defense (DoD) Secretary issues a determination of military emergency or significant potential for military emergency

- The Department of Homeland Security (DHS) Secretary issues a determination of domestic emergency or significant potential for domestic emergency.

- The Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) Secretary issues a determination of public health emergency or significant potential for public health emergency

- The DHS Secretary issues a material threat determination

After one of the above four determinations is in place, the HHS Secretary can issue a declaration that circumstances exist to justify issuing the EUA. This declaration is specific to EUAs and is not linked to other types of emergency declarations.

The FDA Commissioner, in consultation with the HHS Assistant Secretary for Preparedness and Response (ASPR), Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), and the National Institutes of Health (NIH), can then issue the EUA, if criteria for issuance under the statute are met. FDA publishes public notice of each EUA that is issued in the Federal Register.

The last step in the process is termination of declaration and EUA, if appropriate and needed.

Interim Updated Planning Guidance on Allocating and Targeting Pandemic Influenza Vaccine during an Influenza Pandemic

Tuesday, November 6th, 2018“Effective allocation and administration of pandemic influenza vaccine will play a critical role in preventing influenza and reducing its effects on health and society during a future pandemic. Although the timing and severity of a future pandemic and characteristics of the next pandemic influenza virus strain are not known, it is important to plan and prepare. The overarching aim of the national pandemic influenza vaccination program is to vaccinate all persons in the United States (U.S.) who choose to be vaccinated, prior to the peak of disease. The U.S. government’s goal is to have sufficient pandemic influenza vaccine available for an effective domestic response within four months of a pandemic declaration. Additionally, plans are to have first doses available within 12 weeks of the President or the Secretary of Health and Human Services declaring a pandemic 1. To meet these timelines, the U.S. government is investing significant resources to create and evaluate new vaccine development approaches and production technologies. Pre-pandemic influenza vaccine stockpiles of bulk vaccine against viruses with pandemic potential are also being established and maintained.

Despite these investments, there are other issues to consider. Stockpiled pandemic vaccine availability will depend on the degree to which they match the circulating pandemic strain and other properties, and manufacturing capacity. In a pandemic, a novel virus has not circulated in humans, and it is assumed that the majority of the population may not have immunity to the virus, causing more people to become ill. Rates of severe illness, complications, and death may be much higher than seasonal flu and more widely distributed. The greater frequency and severity of disease will increase the burden on the health care system, the risk of ongoing transmission in the community, and may increase rates of absenteeism and disruptions in the availability of critical products and services in health care and other sectors. Similarly, homeland and national security and critical infrastructure (e.g., transportation and power supply) could be threatened if illness among critical personnel reduces their capabilities.

Given that influenza vaccine supply will increase incrementally as vaccine is produced during a pandemic, targeting decisions may have to be made. Such decisions should be based on vaccine supply, pandemic severity and impact, potential for disruption of community critical infrastructure, operational considerations, and publicly articulated pandemic vaccination program objectives and principles. The overarching objectives guiding vaccine allocation and use during a pandemic are to reduce the impact of the pandemic on health and minimize disruption to society and the economy. Specifically, the targeting strategy aims to protect those who will: maintain homeland and national security, are essential to the pandemic response and provide care for persons who are ill, maintain essential community services, be at greater risk of infection due to their job, and those who are most medically vulnerable to severe illness such as young children and pregnant women.

Recognizing that demand may exceed supply at the onset of a pandemic, federal, state, tribal, and local governments, communities, and the private sector have asked for updated planning guidance on who should receive vaccination early in a pandemic. This document uses pandemic severity categories based on the current CDC Pandemic Severity Assessment Framework1. Several new elements have been incorporated into the 2018 guidelines to update and provide interim guidance for planning purposes, and to provide the rationale for a new vaccination program during a pandemic allowing for local adjustment where appropriate. These guidelines replace the 2008 Guidance on Allocating and Targeting Pandemic Influenza Vaccine.”

CDC: After Hurricane Florence—Clinical Guidance for Carbon Monoxide Poisoning

Tuesday, September 18th, 2018CDC Health Alert Network (HAN) Health Advisory: Hurricane Florence—Clinical Guidance for Carbon Monoxide (CO) Poisoning

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) sent this bulletin at 09/16/2018 02:56 PM EDT

| CDC issued the following Health Alert Network (HAN) Health Advisory on September 16, 2018. You are receiving this information because you subscribe to COCA email updates. If a colleague forwarded this email to you, yet you would like to receive future updates directly from COCA, click here.

If you have any questions about this or other clinical issues, please e-mail coca@cdc.gov On behalf of the Clinician Outreach and Communication Activity (COCA) |

|||||

|

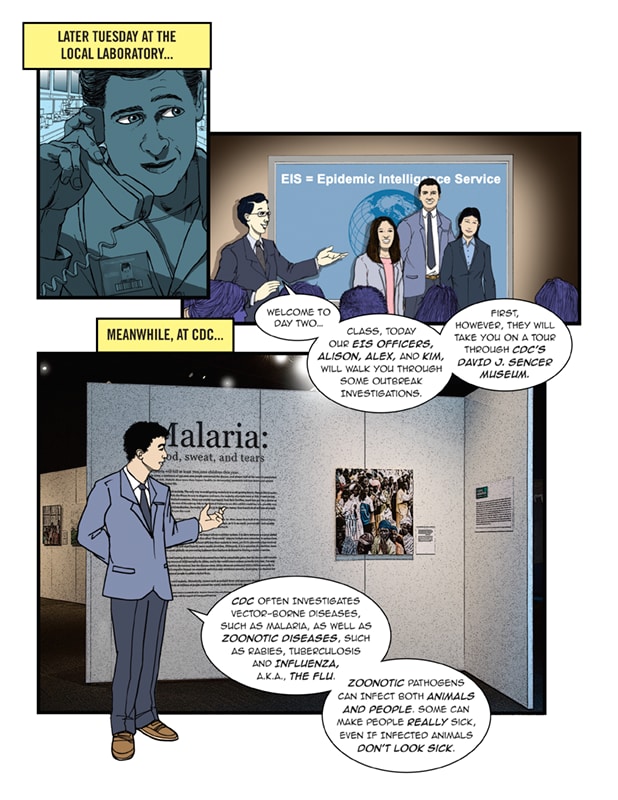

The Junior Disease Detectives: Operation Outbreak Graphic Novel

Tuesday, August 14th, 2018The Junior Disease Detectives: Operation Outbreak Graphic Novel

Download the Graphic Novel

CDC has partnered with the U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) and 4-H to develop “The Junior Disease Detectives: Operation Outbreak,” a graphic novel intended to educate youth audiences about variant flu and the real disease detective work conducted by public and animal health experts when outbreaks of infectious diseases occur.

This graphic novel follows a group of teenage 4-H members who participate in a state agricultural fair and later attend CDC’s Disease Detective Camp in Atlanta. When one of the boys becomes sick following the fair, the rest of the group use their newly-acquired disease detective knowledge to help a team of public and animal health experts solve the mystery of how their friend became ill.

Educational Activities for the Classroom

CDC has partnered with teachers participating in its Science Ambassador Fellowship to develop educational activities to accompany the graphic novel for use in middle and high school science, technology, engineering and mathematics (STEM) classrooms. The activities highlight themes in the graphic novel to teach youth about public health science, epidemiology, biology, outbreak investigations and associated career skills. The graphic novel and its associated educational activities are part of a broader CDC initiative with USDA and other agricultural partners to raise awareness, knowledge and understanding of a One Health approach to zoonotic disease prevention and response. The activities below are available for free download and use, and additional classroom activities will be developed and posted to this site throughout the 2018-2019 school year.

- Educational Overview (COMING SOON): This document describes the learning objectives associated with the graphic novel and also topics related to influenza (flu) epidemiology, flu biology, zoonotic diseases, variant flu, novel flu and pandemic flu.

- Activity 1 – The Operation Outbreak Team (COMING SOON): In this activity, students learn the various roles and responsibilities of the professionals involved in an outbreak response.

- Additional classroom activities will be in the summer and fall of 2018