Archive for the ‘CDC’ Category

CDC: 1918 Pandemic Flu Partner Webinar

Sunday, August 5th, 2018Transcript: 1918 Pandemic Partner Webinar — Commemorating 100 Years Since the 1918 Flu Pandemic

MODERATOR: Good Afternoon and thank you for joining us today. I’m Nancy Messonnier, Director of the National Center for Immunization and Respiratory Diseases at CDC. And I am delighted to have you join us today for our partner webinar entitled, Commemorating 100 Years Since the 1918 Flu Pandemic. The 1918 Flu Pandemic was a historic global event that killed more people than World War I, II and the Korean and Vietnam Wars combined. It is one of the most devastating health events in recorded world history. Next year marks 100 years since this historic event and we at CDC would like to take this opportunity to recognize just how far we have come in our understanding of the influenza virus, our ability to monitor and track circulating viruses in development of a vaccine and our nation’s preparedness capabilities. We also know that there is much more work that can be done to make us better able to respond to the next pandemic. And we know that it is not a question of if we will have another pandemic, but a question of when. Today’s webinar speaker is Dr. Dan Jernigan, Director of the Influenza Division at NCIRD, CDC. Dr. Jernigan will provide a brief historic overview of the pandemic and highlight achievements over the past 100 years. And also, identify opportunities to improve our ability to detect and respond to pandemic influenza. Dr. Jernigan will also share information on CDC’s commemoration objectives and resources to hopefully facilitate your organization’s involvement in commemorating 2018 as the century of the 1918 pandemic should you be interested in doing so. Most importantly, we’re interested in hearing from you, our partners, on ideas for highlighting this historic event. We look forward to hearing from you and working with you over the coming year. Thank you and now I’ll turn it over to Dr. Jernigan.

DR. DANIEL JERNIGAN: Thank you very much Dr. Messonnier. So it’s a great opportunity for me to talk with so many partners who have been with us for so many other activities. And I think this one in particular, is an opportunity to talk about something that was terrible that happened many years ago that could happen again maybe. We’re trying to predict that, trying to forecast that better, but at this point, I think it’s good to see what happened, understand it and see where we are now and figure out are we ready really now to respond something as devastating as happened in 1918. Even if it were half as bad, are we there right now? So what I’d like to do is go to the next slide and talk about a couple of things today; I want to talk about the 1918 pandemic first and then also talk about some of the current influenza threats that we’re seeing, especially from Asia right now, the influenza H7N9. And then talk a little bit about where we are with pandemic readiness like Dr. Messonnier mentioned and then get input from you on the 1918 commemoration activities that are being planned, but also ways that the information that we talk about today can be incorporated into influenza messages and into the activities that you’re doing with regard to pandemic and other readiness and preparedness issues. If you go to the next slide here, to talk a little bit about influenza, there is a significant annual burden of influenza in humans. Off on the left side you can see the total numbers that we have from the United States, on the right, the global numbers. Really, in a severe season, you can have upwards of 56,000 deaths, 710,000 hospitalizations in the U.S. along, 35 million cases and that’s translated to many more cases, of course, globally. These estimates globally are a little hard to get at, but some recent studies that have come out from Dr. Iuliano in our Influenza Division actually have estimated upwards of 600,000 deaths occurring per year just from seasonal influenza alone. On this slide you can actually see the problem that we’re talking about. Influenza, of course as most folks know, is constantly changing; the reason that it’s able to change is because the inside of the virus has separate genes that can be switched from one virus to another. And those inside genes actually code for the proteins that you can see on the outside of these viruses here that are constantly changing to evade the human immunity. That’s the reason why the virus can keep coming back each season and causing influenza in the population. So, human adapted viruses that are on the right can, in certain settings, be in the presence of other viruses that are from avian or swine origin and at that point, can actually exchange their genes and develop a whole new type of influenza virus. And so that’s really what can prompt a pandemic and that is a virus that is not been seen in the human population or has been not seen for a very long time and which is able to transmit from person-to-person in a very sustained way, meaning it can go from person to person to person and in an efficient way. It can go from one person to more than one person. So once it achieves that, you can then have the transmission of a brand new virus within the population. And we’ve had four of those in the last 100 years and I’ll talk a little bit about those pandemics when they’ve occurred. On this slide, you can actually see the lineages of the influenza A viruses that have been happening since 1918. Off to the left you can see when this 1918 H1N1 first showed up with, perhaps, 675,000 deaths reported in the United States. It was with us for a number of years. Around 1947 there were some changes that the H1N1 underwent that actually made it a little bit different than what was there previously and in 1957 it was completely replaced by the H2N2 during the 1957 pandemic with around 116,000 deaths at that time. That virus was with us for around ten years and then in 1968, H3N2 showed up and so we are commemorating not only the 100th anniversary of 1918, we’re also commemorating the 50th anniversary of the 1968 pandemic with around 100,000 deaths at that time. H3N2 has been with us for those 50 years and has continued to change and continued to be the virus that is more likely to cause severe cases, hospitalizations, deaths, and etcetera, relative to H1N1. So H1N1 actually showed back up in 1977 for reasons that aren’t exactly clear and was with us in the form that it was up until 2009 when H1N1…but a H1N1 that was actually much more similar to what was happening back in 1918 reappeared in the U.S. population. And the reason it came was that it came from humans in the 1930’s, went into the pig population, was in pigs for a number of years changing and reasserting and then came back out probably in North America, in Mexico, and then began going around the world very rapidly with the 2009 pandemic. So going to the next slide, let me talk a little bit about the first of those and that of course is the 1918 pandemic that we’re commemorating at the 100 years right now. So one thing that facilitated the transmission was crowding and so these pictures, I think, really demonstrate what was happening, especially in urban areas where people were moving to cities so that they could get jobs and assist with the war efforts that were really starting around that time. People were living in very close quarters, sometimes sleeping during the day and then going to work at night and somebody else sleeping in the beds; it was a very crowded situation because of industrialization in the war response. And in addition, because of that World War I response, soldiers were also in very crowded conditions; sometimes 100,000 were in tents at one point, especially over the winter in 1917-18 where there was a very cold winter. So overcrowding, cold winter and these are, you know, young men that were brought from say, Kansas, all the way across the U.S. and then put together; so a bunch of naïve, young men that were actually then able to spread easily, different kinds of infections, not just flu but also measles and other things as well. Other things that were aiding transmission were the wartime movement. These pictures, I think, tell a lot, especially the lower picture I think really is the one that describes exactly the issues that were there. There was massive troop movement. They were moving from towns, like I said in maybe Kansas or elsewhere, to training bases and then to Europe. There were, for a period of time in the summer of 1918, 10,000 men being shipped to France every day. This was an unprecedented troop movement that allowed infection to move from camp to camp and it also allowed the virus to have opportunities for quickly getting around the globe in naïve populations that just probably weren’t there in the previous century. Where were the first cases? There’s actually a lot of controversy around where the cases of flu actually started. Some actually believe, the historians believe, that it may have actually started in the United States, in Kansas; the first reports were in March 30th of 1918. We were able to pull up one of those reports and put it here. So it is possible that it started from a swine source or an avian source that had also some swine associated with it. But the funny thing is that the pandemic is often referred to as the Spanish Flu and it’s not the Spanish Flu because it came from Spain; it was called the Spanish Flu because they were the first ones to talk about it. And I think that’s actually an important point about the communications about infectious diseases during that time during the war. All those countries that were combatants in World War I were not willing to mention that their troops might be decimated by an emerging pandemic and so we’re not talking about it. Spain was actually a non-combatant and because of that, they were ones that did not refuse to admit having cases and then got the moniker then of Spanish Flu. Other things happening at that time, it was the dawn of modern medicine, of viruses that had not been discovered yet, there was no flu treatment or prevention, flu transmission was also poorly understood. There’s a picture of a doctor down to the lower right, Dr. Pfeiffer, who had identified a bacillus, which later was called Haemophilus influenzae because it was considered to be a cause of influenza. It later turned out to be likely a secondary bacterial cause. But during the pandemic, this was considered to be one of the sources of the pandemic. There were very few vaccines. There were only palliative therapies including things like turpentine and beef tea, things that may have caused more harm than actually helping. And one in important point was that greater than 30% of doctors and nurses were working for the military, so hospitals and clinics were greatly short staffed because a lot of the medical group were actually trying to support the war effort. Some signs and symptoms of the 1918 pandemic, I think the picture to the right really shows graphically what was actually happening per person. This was a drawing put together so that they could quickly explain to people the phases of the illness. Most people, of course, had classic flu symptoms. In about 10 to 20% of cases there was pneumonia, but they described what was called Purple Death, where the quotes that are listed here, “They very rapidly developed the most vicious type of pneumonia that has ever been seen.”; “Cyanosis extending from their ears and spreading all over the face until it’s hard to distinguish the coloured men from the white.”; “It takes special trains to carry away the dead. For several days there were no coffins and the bodies piled up something fierce.”; and then “Bodies stacked in the morgue from floor to ceiling like cord wood.” So this was a terrible situation and in fact, a young physician was asked what he should do to prepare to go and assist with the treating pandemic for the war effort and he was told that you should learn how to build coffins. So this was a terrible time with the significant amount of illness, especially in the younger individuals. The graph here at the top shows the three pandemic waves that came pretty quickly, one after another with high fatality. There were an estimated 50, some say upwards of 100 million deaths globally. There were five times the military losses of World War I were due to the pandemic. And the graph to the…the lower graph there shows that the depressed overall average life expectancy of 12 years because of what was happening in terms of the increased deaths during the 1918 pandemic. How do we know why it was so severe? An interesting activity that happened in 1951 was with a researcher named Johan Hultin, who you can see in the picture there to the upper left, was with some other researchers in Brevig Mission, Alaska where they decided they would exhume some frozen bodies from Brevig Mission who had all died from pandemic flu in 1918. They were able to find those bodies, get the appropriate approvals from the tribe and then recover lung tissue. In 1951, in that upper middle picture, you can see where Hultin was actually trying to grow the virus, but was not able to. And then, in 1997, the same man heard about what was happening with Jeffery Taubenberger, who was with the Armed Forces Institute of Pathology, at the time, where they were sequencing the virus from tissues directly. And so he decided to go back to the gravesite, get the appropriate approvals and recover additional frozen lung tissue. so he was able to do that, provide that to Jeffery Taubenberger, who began doing all of the sequencing on that and then those sequences of the virus were provided to Terry Tumpey that is here at CDC, who was able to actually reconstruct and rescue the 1918 virus in the high containment lab there. And then, do studies with that virus with mice and with other mammals to determine what were the reasons why it was so severe and he identified that there were some changes in the outer surface protein, the hemagglutinin and with one of the polymerase genes inside the virus that was associated with causing more severe disease. So this rescuing of the virus really was using the latest technology at the time, which has continued to improve and is now able to let us see what was happening with that virus even though it was 100 years ago. So of the three pandemics that are listed here, the H1 in 1918, the H2 in ’57 and the H3 in ’68, all three of these had hemagglutinin genes, that is the outer surface proteins, that were of avian origin and that’s important because of what we’re seeing right now with some of the emerging new influenza viruses. One of them, let me spend a little time talking about, because it’s of concern to CDC and to WHO and others, of the H7N9 in Asia. This is a virus that if you want more information on it, you can actually look at this report from September 8th, there are others that are out there as well since that time, from the MMWR where we described what happened during the fifth wave, which was just last year, the ’16-’17 season. If you want to get a shorthand for H7N9, it’s basically…the risk factors are old men in bird markets and so it tends to happen more in men, those that are over age 65 and definitely those that have had exposure in the bird markets in China. This graph shows the cumulative number of cases of H5N1, which is a concerning virus that we’ve been following for a number of years, as well as the H7N9, which appeared in 2013. And so as you can see, the H7N9 cases have really increased dramatically, upwards of 1,500 and have outpaced the other most concerning virus that we had at the time, the H5. And so this rapid increase in the numbers of cases and the distribution of the virus throughout China has made it of great concern to us to monitor very closely. The H7N9 in humans has about 90% of them develop pneumonia, 70% of them are admitted to the ICU and 40% of the cases have died; so of around 1,500 cases, 40% have died. There have been clusters of infection, through the China CDC and other partners have investigated 35 of those and there’s not been any sustained or efficient human-to-human transmission. The fifth wave viruses, the ones from 2016-17 are certainly increasing in number; they are increasing in the numbers of provinces where they are causing disease in China, they’ve been changing such that we now have to have a new pre-pandemic vaccine that the Federal government has developed for use in first responders in the United States and the subset of viruses are now actually causing significant disease in poultry, so almost 100% die-off of certain flocks due to this virus now. So this is a bad virus. It raises the question then, if something like the H7N9 were to appear and were able to actually change, there’s a study that actually just came out not too long ago showing that just three changes to the genes in the H7N9 could make it more transmissible between mammals and humans. So, if that were to happen, are we ready for a pandemic like that? There was a lot of discussion about this in the past, especially renewed interest in pandemic during the mid-2000s, and there are a lot of factors that are associated with the potential for pandemic. The world is, of course, more crowded, it’s more connected and the worlds of humans and animals are increasingly converging. And if the 1918 pandemic were to occur today, it could result in tens of millions, some say upwards of 100 million deaths globally and would infect probably around 20 to 30 % of the global population for the first couple of waves. It would likely be potentially disruptive of transportation and supply chains. A lot of our food, a lot of our pharmaceutical supplies, a lot of our energy actually comes from outside the United States so it could be disruptive in that way. And it certainly would be disruptive of healthcare services. This season there’s a lot of folks going into the emergency departments, going into hospitals because of this year’s seasonal flu and you can see the impact that that’s having in certain parts of the U.S. right now, you can imagine what would happen in the U.S. if we were to have a much more fatal, more transmissible infection due to a pandemic. The potential costs are also high. It’s been estimated of around $181 billion dollars for pandemic, influenza pandemic. And then also, looking back at SARS with the total amount that it costs was around $30 billion in only four months. And so that’s what we might expect. So what is the Federal government doing? We’ve had planning tools and other tools out there, but this year, in April, there was a release of the 2017 Health and Human Services Pandemic Influenza Plan and it goes through the different activities that are listed here on this one page. And so this actually helps us to say this is what we should be working on, it’s a strategy, but there’s still a lot that needs to be done in terms of specific influenza pandemic planning at the state level and certainly in other countries as well. So, looking at different parts of that document and just asking the question, are we ready? What are the strengths that we have that have occurred in the last few years and what are our gaps? From the standpoint of surveillance and diagnostic readiness, the strengths are clearly that there’s much greater global surveillance and reagent distribution for influenza. We currently distribute through our international reagent resource, PCR testing reagents for 143 different laboratories around the globe that helps us to identify these novel viruses. We’ve had greatly improved domestic flu surveillance in the United States as well. And there are new technologies like next generation sequencing that’s being performed at CDC for all the flu viruses that we receive, including a recent development that we have, in that picture at the bottom there, of a handheld next generation sequencer that we can take into the field and actually test people and get results very quickly to help determine what the risk is and make decisions quickly about what to do. However, there are still lots of gaps. We clearly have inadequate surveillance in birds and swine and there are places where we don’t have information about what’s happening with flu. Some have referred to those at data deserts, especially in Africa and in other developing countries. With regard to treatment and clinical care, some strengths are that we [23:30-24:16 TECHNICAL DIFFICULTY]…okay, sorry about that. So in terms of treatment and clinical care, you’ve had a lot of opportunity to read this slide I take it, there are more antivirals, of course, they’re listed there, including Peramivir, which is a new antiviral drug that’s not available for intravenous use in children. There are also stockpiles maintained, certainly in the U.S. and in other countries that are available for use, but it’s clearly not going to be enough in those stockpiles. But there are gaps, we need better performing antivirals. The current ones we have that are the neuraminidase inhibitors are just not as effective as they should be; they have to be used early in the course of illness. And so, there’s promise in the development of these new antivirals, but they’re just not where they are now. We also need to have reusable respiratory protective devices and better ventilator access if we were to have a significant pandemic that impacted the healthcare system. And many, I think, would indicate, especially those that are dealing with flu right now, that the healthcare system could get easily overwhelmed in a severe pandemic. In terms of vaccine readiness, we have better forecasting for which viruses are actually the ones that should be put into the vaccine. We have new technologies like the ability to make the viruses to put in the vaccines. We can make vaccines in cells now instead of in eggs. We can have vaccines that are made from proteins only, not requiring the eggs as well. And there’s more manufacturing capacity available and there are new programs like what’s listed here, the PIVI Program, for introducing vaccine for low and middle income nations. However, it just takes too long to have vaccine available for a pandemic response and so things need to happen to make the current system more efficient and more able to respond quickly to making a vaccine. And of course, it would be wonderful if we could have a better truly universal vaccine that we could give once or twice in life and have it cover all types of influenza, but that’s going to be many years away. So, improving the current vaccines so that we can be better responding for pandemics, but also for treating flu, is critical. In terms of pandemic planning and response, that we have better tools for responding to a pandemic, there’s new frameworks and new mitigation guidance that you can find on the web at CDC website. However, most countries don’t have robust pandemic plans and very few exercise their response efforts. And an important issue that’s been identified is that only a third of all countries are prepared to meet global health security for WHO readiness targets. So, in conclusion, regarding the 1918 and whether we’re ready, influenza viruses are constantly changing requiring ongoing surveillance and frequent vaccine virus changes. Pandemics can vary in severity, the 1918 pandemic was exceptionally severe and if a similar pandemic were to happen today with that level of severity, it certainly would cause a significant illness and death. The number of detected emerging novel influenza viruses is increasing, requiring ongoing laboratory and epidemiologic investigations for risk assessments. And efforts to improve pandemic readiness and response are underway, however, many gaps remain. So let me talk then a little bit about some commemoration objectives and some resources that are available for many of the partners to use as they would like. The communication objectives for this effort are to underscore the continued threat of pandemic influenza, to highlight the public health achievements in influenza preparedness and response, to identify pandemic flu preparedness gaps in areas in need of further investment and empower people to act in order to decrease their risk of seasonal and pandemic influenza. The importance of vaccination of course and those actions that they can take, that an individual can take, to help to protect themselves, but also to protect their loved ones during a pandemic. So those are the objectives. What can the partners do? I think the use of the 1918 commemoration as a platform for collective public health preparedness messaging is important. And how can that be done? Through communications; collaborating with CDC and other agencies and other academic facilities and collaborating with each other on creative communications activities, having events; incorporating 1918 messaging into conferences or meetings and press events, some of those are already becoming…you can see them on the web, but I think there’s an opportunity for a lot more of these other events that could incorporate 1918 into the presentation. And then other creative ideas, we would love to hear from you to share with us what you would think would be useful for spreading the word about what happened in 1918, but also about how we can become more prepared and how we can also take measures now for seasonal influenza as well. So what are some of the resources for the partners? There is a 1918 commemoration webpage that will be available to folks that is currently nearing the end of development, but that will be available to folks. There are master key points and messaging that is available, specifically on this topic, that helps bridge to other preparedness and influenza issues. Infographics will be available and a digital timeline from 1918 to the present. It would be nice to have your support and we would love to hear your ideas on ways the commemoration can be incorporated into communications and events and other activities. Some CDC examples of some activities include a symposium that we’re planning with Emory University Rollins School of Public Health. There are other things like this from other academic institutions that are happening and integrating 1918 into conferences and presentations and plenary sessions and publications. So, at this point, I think it would be great to follow-up with folks on what your ideas are. You can contact us at that email address that’s at the top there with your follow-up questions, with your 1918 events that you might want to add to your calendars and requesting any CDC support if you would like, in terms of connecting with partners or resources or event assistance, etcetera. So we would love to have that information from you. I’m going to actually skip to a couple of slides here just since I have everyone captive on the phone and we’re having a pretty significant season. Just to point out that this season is a H3N2 year; I’ve just put up what’s called the ILINet graph, which just shows the numbers of people going to outpatient facilities for influenza-like illness. The red line with the triangles is this year, the pink line or purple line, whatever that is, is the 2014-15 season and you can see that they are tracking right on top of each other. So the earliest of the ’14-’15 season is what we’re seeing this year as well. Both of those seasons were H3N2 seasons, a predominant H3N2 season; 2014-15 many of you remember to being a very severe season and this year, although it’s hard to say exactly, but the severity of this year may turn out to be somewhat similar to what we had in 2014-15. It’s going to take a little time for that information to completely come in. On the last slide here, like I said, it is occurring earlier, it’s similar to 2014-15, most of the viruses are influenza A and most of those are H3N2 so far. There’s no significant drift that we’ve seen of any of the four circulating viruses, however, for the influenza A(H3N2) component of the vaccine, there are some egg-based changes that we’ve seen in the last few years when H3 is circulating that make that egg-based vaccine virus less similar to what’s circulating than the non-egg-based vaccines like the FLUBLOK or the FLUCELVAX and that are an unfortunate problem with the H3 virus trying to grow in eggs; it’s something that people just cannot get around. Recent seasons where A(H3N2) has been predominating, there have been higher hospitalizations and the vaccine effectiveness tends to be lower. So with that, I’m going to head back to the slide here and I think, at this point, folks have been putting their questions up. The first question that came through the text part of the webinar is from Amy [33:59]; it says one of the issues with the 1918 flu pandemic was the health and public officials refused to acknowledge it was happening. In their denial, they encouraged people to do things like attend mass events that worsened the situation. Are we in a place today where officials would be more likely to quickly acknowledge and act on a pandemic? It’s a great question. I think really pointing out the issue that was mentioned earlier in the talk about the war effort and so there were so many factors then that were leading to perhaps poor communication messaging and poor decisions around communication. And so because of that, the description of what was happening just was not…people were not willing to admit that. And I think it’s clear from a number of the historical records and from the reports that we have from back then that people were more interested in getting war bonds than there were in communicating about a rapidly spreading severe pandemic. I would hope that we are in a very different place now. I think our experience through 2009 really demonstrated that being out front communicating that something was happening, also communicating the uncertainty of what was happening and letting folks know that there are things that they can do that would help mitigate things and there are things that both the Federal government, the clinicians and others are also doing to try and mitigate the problem. So, I’m hoping we’re in a much better place than we were back then. The next question comes from Peter [35:42]. I guess I’m not supposed to read all of this, but excellent presentation, thank you very much. He states the 2014 Ebola outbreak produced incidents where the U.S. health care system did not provide the expected standard of care, perhaps out of fear or confusion. What is being done and should be done to prevent the recurrence of this behavior should a pandemic occur? You raise a very important issue. And Ebola and flu are different in many ways; if Ebola had taken off, I think, and some were concerned about, it would’ve been a person-to-person transmission, but much more of what we would call contact transmission; much slower moving thing that you can actually use more traditional methods to prevent. Even so, in areas where they did have that cases, there was a considerable amount of concern of course, in the population, but also there were questions about the capability of healthcare workers to appropriately protect themselves against it. This question is really getting at, if we had a severe pandemic we would actually not just have pockets of cases like Ebola, it would be happening everywhere and therefore, the system would get overwhelmed. Because of that, there are efforts to look at what are called Alternative Standards of Care, there are also ways that we can take existing materials like for instance, a t-shirt, we’re actually looking at CDC to figure out how can use t-shirt material, fold it over several times and use it as a mask for protecting one’s self in the community. So there’s efforts around trying to find some alternative ways in the community that people can protect themselves and then in healthcare settings, there’s a lot of efforts to try to have better respiratory protective devices, ones that could be reused, things like that. But ultimately, I think the…if we had a significant, severe pandemic, it could be devastating to the healthcare system and so there has been discussion about alternatives of care, that is determining who cares, etcetera. It’s a very complicated topic, but there are ethicists and others that are working on that and some efforts have been put into that as well. But clearly, we need to have that articulated prior to us ever having something as severe as the 1918 again.

MODERATOR: And we’ve been asked, we’re summarizing some questions here, but who decides what is considered a pandemic?

DR. DANIEL JERNIGAN: So, a pandemic, just by definition, like we’ve mentioned, is where you have a novel influenza virus for which the population has either no immunity or have very little immunity to and which can transmit efficiently from one person to more than one person and can be sustained. So that’s the simple definition of it. during 2009, the actual global determination, the call, was made by WHO; prior to that though, many countries…we all knew what was actually happening, but I think to have it called a pandemic, the WHO, actually the Emergency Committee is the one I think that makes the final call. However, whether it’s called or not, doesn’t really matter, the activities that the CDC and the Federal government will be doing in order to begin that mitigation cascade of activities will happen. In fact, even with the emergence of a novel influenza virus, in China where there may be two or three cases, we begin that pandemic response by characterizing the virus, developing vaccines, making sure the diagnostics can pick it up and determining whether the antivirals will be effective or not. so, responding to potential pandemics occurs all the time; whether it’s called a pandemic is, from the global standpoint, we work with WHO on that, but from the response standpoint, the U.S. government acts much quicker than that.

MODERATOR: Can you also describe the infrastructure, the importance of infrastructure, in public health in responding to a pandemic?

DR. DANIEL JERNIGAN: So in the United States, a mantra is that our seasonal activities are the infrastructure for our pandemic activities. And so whether they are adequate or not or whether they can scale up is a different question, but our belief is that the best way to be prepared is by having systems that are routinely doing that kind of work. And so, for 2009 we were able to move from weekly reporting up to daily reporting, we added new surveillance systems, we had a whole series of new communication activities, a number of mitigation and community mitigation activities. All of that was done, built on existing infrastructures, at least from the CDC’s standpoint. The vaccine was even delivered using the existing vaccine contracts and the vaccine systems that we have with vaccines for children; all of that, we feel that having the existing infrastructure used for pandemic is important. Is it sufficient? That’s a good question and one way that we look into that is by having exercises so that we check to see is the system that we think going to be used for pandemic able to do it and so we can do that through exercises. And frankly, through the 2009 pandemic, which was sort of the biggest exercise for a bad pandemic.

MODERATOR: Another question we have is what do we think is needed to actually improve flu vaccine?

DR. DANIEL JERNIGAN: So what do we think is needed to improve flu vaccines? I’ll refer to the current vaccines that are out there and so currently, we are able to monitor what’s happening with influenza viruses and we can say what the currently circulating viruses are, what are the predominant ones and we’re even using forecasting now with mathematical modelers and others to try and tick those viruses that are on their way up, the emerging viruses. So that activity, I think, can tell us what’s happening. The issue right now is that the vaccine requires about six months for it to be prepared. And so from a time that a decision is made to start making the vaccine until when it can be injected into people, can be six months. And so in that time, you can see changes in the viruses that are circulating; is what happened in 2014-15. In addition, we are seeing for one component, the H3N2 component, that when they grow in eggs, which is what’s required for the majority of the vaccines out there, there can be changes, there are changes that occur in that virus in order for it to grow in the manufacturing process that make it less similar than what’s actually circulating. And for that reason, having technologies that may not use eggs or finding ways to get viruses that look the same but can grow in eggs, that would be one factor that would be helpful. Things that we are seeing right now though are increased antigen dose, like in those that are over age 65 with the high dose vaccine and also the use of adjuvants, FLUAD and other products that are out there now that use adjuvants. So all of these technologies could possibly make incremental improvements in the vaccine; we’d love to see that. If you can get the vaccine effectiveness just a little bit better, you can actually save significant numbers of cases and deaths, just with improvements in the vaccine effectiveness, of just even 5%. So we look forward to seeing those things, they are happening now as we speak with the high dose, the adjuvanted, the new technologies that are being use; we would love to see more of that to make better vaccines. There’s a question from Michael Parker saying that I heard this flu season has been more severe, is there a mismatch or is it just because H3N2 is the predominant strain this year? So, the main answer to that is it’s the H3N2 because any year we have H3N2 we will have more hospitalizations, more cases, more deaths and it clearly disproportionately impacts those that are at higher risk, those that are over age 65 and the very young. So H3N2 is the primary driver. When we look at the H3N2 viruses that are actually causing disease this year, they don’t look that different than what was with us last year based on the testing that we perform of looking at the outside proteins on the virus. However, we do see that those viruses, when they have to grow in eggs, which is the majority of the vaccine, they are less similar to what’s actually circulating. And so for that reason, there may be an associated lower vaccine effectiveness. We do see in H3 predominant years a vaccine effectiveness of around mid-30’s, 30%, that happens whenever we’re having, that’s the overall vaccine effectiveness over ten years for H3N2. So when we get H3N2, it’s a worse bug and the vaccine effectiveness is not as good and that might be because of some of the egg changes.

MODERATOR: We’ve got a question about what businesses can do to prepare and help people from… keep people from going to work sick and things like that in the event of a pandemic.

DR. DANIEL JERNIGAN: Right, I think both in the pandemic, but also with seasonal flu; one thing is just to allow workers to stay home if they are ill. We know that people want to work and the worst ones are probably the doctors and nurses that come in. And so making it possible for people to be able to telework, making it possible for them to stay home and not infect others, also even allowing them to be in a place at work where maybe they are separated. Those are things that definitely can help in terms of social distancing, that is getting them away from each other so that they are not transmitting as easily. That’s hard, but that’s something that can be encouraged, especially teleworking, to help people to do that. Doing vaccine campaigns at work is very helpful because then it makes it easy for people to get vaccinated and that impact from a vaccine can also help mitigate the issues with seasonal flu. And then there are on the CDC website and also on the CDC Foundation website, tools for businesses that you can access for making sure that businesses are thinking about pandemic and how to respond to them and including influenza seasonal, there’s checklists and other things like that and tools to help folks that are in occupational health and that are over those kinds of issues at large corporations. So thank you very much for the questions that you have given. We would love to hear from folks regarding what you would like to see with the use of 1918; it was a significant period of time historically. It had an impact on our survivability; it actually is something that you can see clearly the amount of impact from deaths due to the 1918 pandemic. Remembering that 100 years later, I think is important. It makes it clear to us that there are things that we can do to get ready. Influenza is a severe disease and so we want to take it seriously and make sure that if something like this were to happen again, that we would be more prepared than we are. So with that, thank you very much and I look forward to hearing from you all.

END.

CDC Pandemic Flu Fighters

Thursday, June 28th, 2018Influenza poses one of the world’s greatest infectious disease challenges. The 1918 flu pandemic is a stark reminder of the devastation that can result from a global flu pandemic. CDC and its public health partners around the world work diligently to monitor and prepare for the next flu pandemic. Highlighted below are some of CDC’s flu fighters, dedicated public health professionals contributing to pandemic flu prevention and response at home and around the world.

Amra Uzicanin, MD, MPH, Team Lead, CDC’s Community Interventions for Infection Control Unit

As Lead of CDC’s Community Interventions for Infection Control Unit (CI-ICU), Dr. Amra Uzicanin is dedicated to developing the scientific evidence base and policies for use of nonpharmaceutical interventions (NPIs), for infectious disease control in community settings with a focus on pandemic flu. NPIs, also known as community mitigation measures, are the first line of defense to help slow the spread of pandemic influenza (flu). NPIs are readily available everywhere and can be used before a pandemic vaccine is available. CI-ICU works hard to prevent and reduce the spread of infectious diseases in communities by empowering people and communities to take action grounded in evidence-based knowledge of NPIs. Dr. Uzicanin says the 1918 flu pandemic “was a pandemic where ordinary people and communities as well as government authorities, public health officials, and healthcare professionals were striving to find new ways to fight off the flu and prevent its impact worldwide.”

Anita Patel, PharmD, MS, Team Lead, CDC’s Pandemic Medical Care and Countermeasures

Dr. Anita Patel is one of CDC’s key problem solvers working to protect the United States from a future influenza pandemic. Her responsibilities include making sure the nation has strategies in place for medical countermeasures to be able to treat sick patients and protect health care workers. Dr. Patel says the 1918 flu pandemic is a sobering reminder of the dangers of flu. “Learning from history allows us to plan for the possible range of impacts, and move the needle in preparedness.”

Anne Schuchat, MD (RADM, USPHS) CDC Principal Deputy Director

Principal Deputy Director of CDC, Dr. Anne Schuchat, is one of the many veterans of CDC’s fight on flu. Combatting influenza is a hallmark of Dr. Schuchat’s 30 years at CDC. In reflecting on the 1918 influenza pandemic, Dr. Schuchat says studying what happened can help us to better prepare the nation and the world for similar scenarios in the future.

Daniel Jernigan, MD, MPH (CAPT, USPHS), Director, Influenza Division

Dr. Dan Jernigan, a captain in the United States Public Health Service (USPHS), serves as director of the Influenza Division in CDC’s National Center for Immunization and Respiratory Diseases. In this role, Jernigan is always working to prepare for the next influenza pandemic. “We are determined to intervene where we can to stop the spread of disease—that’s public health,” he says. For CDC’s Influenza Division, stopping the spread of disease means, “tracking influenza viruses and human illness with influenza viruses worldwide – be it from seasonal, avian, swine, or other novel flu viruses. We track illness, study the virus, assess the risk posed by the virus, make vaccine viruses that are then used to manufacture flu vaccines and help make policies for influenza prevention and treatment.”

James Stevens, Ph.D., Associate Director, Laboratory Sciences in CDC’s Influenza Division

CDC’s influenza laboratories play a leading role in the ongoing global task of looking for new flu viruses, assessing the risk they pose to people, and supporting efforts to proactively prepare for the emergence of flu viruses considered to have pandemic potential. This includes everything from conducting surveillance on novel influenza viruses, to developing the viruses that are used to mass-produce flu vaccines, which are called “candidate vaccine viruses” or “CVVs”. As Associate Director for Laboratory Sciences in CDC’s Influenza Division, Dr. James Stevens oversees and coordinates CDC’s influenza laboratory operations. He says the 1918 flu pandemic “is the deadliest we’ve seen in modern times. We have to remember it because it is the worst-case scenario situation, and we don’t want it to happen again.”

Lisa Koonin, DrPH, MN, MPH, Deputy Director, Influenza Coordination Unit

Martin Cetron, MD, Director, Division of Global Migration and Quarantine (DGMQ)

Air travel today can easily facilitate the spread of diseases around the world with each flight. CDC’s Division of Global Migration and Quarantine (DGMQ) helps protect the health of our communities in a globally mobile world. As director of DGMQ, Dr. Martin (Marty) Cetron is a leader in global health and migration with a focus on emerging infections, tropical diseases, and vaccine-preventable diseases in mobile populations. He says the 1918 influenza (flu) pandemic was “monumental, and as an unprecedented event in human history, it taught us some really important lessons.

Stephen Redd, MD (RADM, USPHS) Director, Office of Public Health Preparedness and Response

CDC’s Dr. Stephen Redd has deep and diverse experiences in responding to public health emergencies, including the 2009 H1N1 influenza pandemic during which he served as incident commander for the CDC’s response. For the past four years, Dr. Redd has directed CDC’s Office of Public Health Preparedness and Response, the group responsible for ensuring CDC is prepared to respond to a public health emergency.

Terrence Tumpey, Ph.D., Chief, Influenza Immunology and Pathogenesis Branch

Dr. Terrence Tumpey is a microbiologist and chief of the Immunology and Pathogenesis Branch (IPB) in the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s Influenza Division. He’s perhaps best known for his groundbreaking work reconstructing the 1918 pandemic influenza virus. In 1918, this virus was responsible for the pandemic that is estimated to have killed at least 50 million people worldwide. In 2004, Dr. Tumpey was the first to physically reconstruct, or “rescue” the 1918 virus, using reverse genetics to build an H1N1 virus with all the same genes as the pandemic virus. After the reconstruction was completed, Dr. Tumpey was the first person to study the live 1918 H1N1 virus in the laboratory.

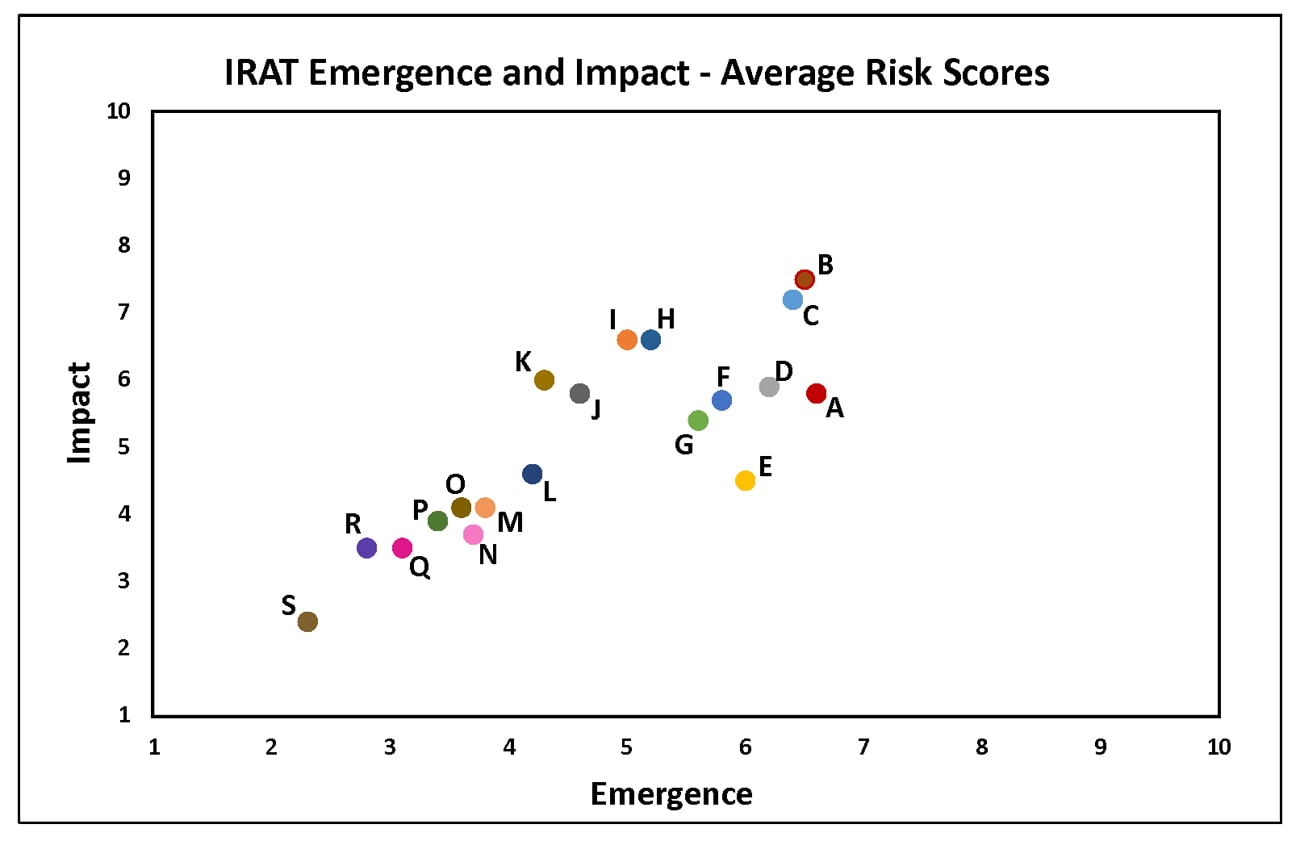

Summary of Influenza Risk Assessment Tool (IRAT) Results: 2018

Tuesday, June 5th, 2018The Influenza Risk Assessment Tool (IRAT) is an evaluation tool conceived by CDC and further developed with assistance from global animal and human health influenza experts. The IRAT is used to assess the potential pandemic risk posed by influenza A viruses that are not currently circulating in people. Input is provided by U.S. government animal and human health influenza experts. Information about the IRAT is available at Influenza Risk Assessment Tool (IRAT) Questions and Answers(https://www.cdc.gov/flu/pandemic-resources/national-strategy/risk-assessment.htm).

| Virus | Most Recent Date Evaluated | Potential Emergence Risk(https://www.cdc.gov/flu/pandemic-resources/tools/risk-assessment.htm#emergence-risk) | Potential Impact Risk(https://www.cdc.gov/flu/pandemic-resources/tools/risk-assessment.htm#impact-risk) | Overall Summary |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| H1N1 [A/duck/New York/1996] | Nov 2011 | 2.3 | 2.4 | Low |

| H3N2 variant [A/Indiana/08/2011] | Dec 2012 | 6.0 | 4.5 | Moderate |

| H3N2 [A/canine/Illinois/12191/2015] | June 2016 | 3.7 | 3.7 | Low |

| H5N1 Clade 1 [A/Vietnam/1203/2004] | Nov 2011 | 5.2 | 6.6 | Moderate |

| H5N1 [A/American green-winged teal/Washington/1957050/2014] | Mar 2015 | 3.6 | 4.1 | Low-Moderate |

| H5N2 [A/Northern pintail/Washington/40964/2014] | Mar 2015 | 3.8 | 4.1 | Low-Moderate |

| H5N6 [A/Yunnan/14564/2015] – like | Apr 2016 | 5.0 | 6.6 | Moderate |

| H5N8 [A/gyrfalcon/Washington/41088/2014] | Mar 2015 | 4.2 | 4.6 | Low-Moderate |

| H7N7 [A/Netherlands/219/2003] | Jun 2012 | 4.6 | 5.8 | Moderate |

| H7N8 [A/turkey/Indiana/1573-2/2016] | July 2017 | 3.4 | 3.9 | Low |

| H7N9 [A/chicken/Tennessee/17-007431-3/2017] | Oct 2017 | 3.1 | 3.5 | Low |

| H7N9 [A/ chicken/Tennessee /17-007147-2/2017] | Oct 2017 | 2.8 | 3.5 | Low |

| H7N9 [A/Hong Kong/125/2017] | May 2017 | 6.5 | 7.5 | Moderate-High |

| H7N9 [A/Shanghai/02/2013] | Apr 2016 | 6.4 | 7.2 | Moderate-High |

| H9N2 G1 lineage [A/Bangladesh/0994/2011] | Feb 2014 | 5.6 | 5.4 | Moderate |

| H10N8 [A/Jiangxi-Donghu/346/2013] | Feb 2014 | 4.3 | 6.0 | Moderate |

H1N1: [North American avian H1N1 [A/duck/New York/1996]

Avian influenza A viruses are designated as highly pathogenic avian influenza (HPAI) or low pathogenic avian influenza (LPAI) based on molecular characteristics of the virus and the ability of the virus to cause disease and death in chickens in a laboratory setting. North American avian H1N1 [A/duck/New York/1996] is a LPAI virus and in the context of the IRAT serves as an example of a low risk virus.

Summary: The summary average risk score for the virus to achieve sustained human-to-human transmission was in the low risk category (less than 3). Similarly the average risk score for the virus to significantly impact public health if it were to achieve sustained human-to-human transmission also falls into the low risk range (less than 3).

H3N2 Variant:[A/Indiana/08/11]

Swine-origin flu viruses do not normally infect humans. However, sporadic human infections with swine-origin influenza viruses have occurred. When this happens, these viruses are called “variant viruses.” Influenza A H3N2 variant viruses (also known as “H3N2v” viruses) with the matrix (M) gene from the 2009 H1N1 pandemic virus were first detected in people in July 2011. The viruses were first identified in U.S. pigs in 2010. In 2011, 12 cases of H3N2v infection were detected in the United States. In 2012, 309 cases of H3N2v infection across 12 states were detected. The latest risk assessment for this virus was conducted in December 2012 and incorporated data regarding population immunity that was lacking a year earlier.

Summary: The summary average risk score for the virus to achieve sustained human-to-human transmission was in the moderate risk category (less than 6). The summary average risk score for the virus to significantly impact public health if it were to achieve sustained human-to-human transmission was in the low-moderate risk category (less than 5).

H3N2: [A/canine/Illinois/12191/2015]

The H3N2 canine influenza virus is an avian flu virus that adapted to infect dogs. This virus is different from human seasonal H3N2 viruses. Canine influenza A H3N2 virus was first detected in dogs in South Korea in 2007 and has since been reported in China and Thailand. It was first detected in dogs in the United States in April 2015(https://www.cdc.gov/flu/news/canine-influenza-update.htm). H3N2 canine influenza has reportedly infected some cats as well as dogs. There have been no reports of human cases.

Summary: The average summary risk score for the virus to achieve sustained human-to-human transmission was low risk (less than 4). The average summary risk score for the virus to significantly impact public health if it were to achieve sustained human-to-human transmission was in the low risk range (less than 4). For a full report, click here[186 KB, 4 pages](https://www.cdc.gov/flu/pandemic-resources/pdf/cdc-irat-virus-canine-h3n2.pdf).

H5N1 clade 1: [A/Vietnam/1203/2004]

The first human cases of highly pathogenic avian influenza (HPAI) H5N1 virus were reported from Hong Kong in 1997. Since 2003, highly pathogenic H5N1 avian influenza viruses have caused over 850 laboratory-confirmed human cases; mortality among these cases was high. A risk assessment of this H5N1 clade 1 virus was conducted in 2011 soon after the IRAT was first developed and when 12 hemagglutinin (HA) clades were officially recognized.

Summary: The summary average risk score for the virus to achieve sustained human-to-human transmission was in the moderate risk category (less than 6). The summary average risk score for the virus to significantly impact public health if it were to achieve sustained human-to-human transmission was in the high-moderate risk category (less than 7).

H5N1: [A/American green winged teal/Washington/1957050/2014]

In December 2014, an H5N1 highly pathogenic avian influenza virus was first isolated from an American green-winged teal in the state of Washington. This virus is a recombinant virus containing four genes of Eurasian lineage (PB2, HA, NP and M) and four genes of North American lineage (PB1, PA, NA and NS).In February 2015, the Canadian government reported isolating this virus from a backyard flock in the Fraser Valley. When this risk assessment was conducted in 2015, these were the only reported isolations of this virus. There have been no reports of human cases.

Summary: The summary average risk score for the virus to achieve sustained human-to-human transmission was in the low risk category (less than 4). The summary average risk score for the virus to significantly impact public health if it were to achieve sustained human-to-human transmission was in the low-moderate risk category (less than 5).

H5N2: [A/Northern pintail/Washington/40964/2014]

In December 2014, an H5N2 highly pathogenic avian influenza virus was first reported by the Canadian government from commercial poultry in the Fraser Valley.Subsequently this virus was isolated from wild birds, captive wild birds, backyard flocks and commercial flocks in the United States.This virus is a recombinant virus composed of five Eurasian lineage (PB2, PA, HA, M and NS) genes and three North American lineage (PB1, NP and NA) genes. There have been no reports of human cases.

Summary: The average summary risk score for the virus to achieve sustained human-to-human transmission was low risk (less than 4).The average summary risk score for the virus to significantly impact public health if it were to achieve sustained human-to-human transmission was in the low-moderate risk range (less than 5).

H5N6: [A/Yunnan/14564/2015 (H5N6-like)]

Between January 2014 and March 2016, there have been 10 human cases of H5N6 highly pathogenic avian influenza reported. Nine reportedly experienced severe disease and six died. Avian outbreaks of this virus were first reported from China in 2013. Subsequently avian outbreaks have been reported in at least three countries (China, Vietnam and Lao PDR) through 2015.

Summary: The summary average risk score for the virus to achieve sustained human-to-human transmission was in the moderate range (less than 6).The average summary risk score for the virus to significantly impact on public health if it were to achieve sustained human-to-human transmission fell in the moderate range (less than 7).

H5N8: [A/gyrfalcon/Washington/41088/2014]

In December 2014, an H5N8 highly pathogenic avian influenza virus was first isolated from a sample collected in the United States from a captive gyrfalcon.Subsequently this virus was isolated from wild birds, captive wild birds, backyard flocks and commercial flocks in the United States.This virus (clade 2.3.4.4) is similar to Eurasian lineage H5N8 viruses that have been isolated in South Korea, China, Japan, the Netherlands, the United Kingdom and Germany in late 2014-early 2015.There have been no reports of human cases.

Summary: The average risk score for the virus to achieve sustained human-to-human transmission was in the low-moderate range< (less than 5). The average summary risk score for the virus to significantly impact public health if it were to achieve sustained human-to-human transmission fell in the low-moderate range (less than 5).

In 2003 the Netherlands reported highly pathogenic avian influenza (HPAI) in approximately 255 commercial flocks.Coinciding with human activities around these infected flocks, 89 human cases of H7N7 were identified.Cases primarily reported conjunctivitis, although a few also reported mild influenza-like illness.There was one death.

Summary: The summary average risk score for this virus to achieve sustained human-to-human transmission was in the low-moderate risk range (less than 5). The summary average risk score for this virus to significantly impact the public’s health if it were to achieve sustained human-to-human transmission fell in the moderate risk range (less than 7).

H7N8: [A/turkey/Indiana/1573-2/2016]

In January 2016, a highly pathogenic avian influenza (HPAI) virus of North American lineage was identified in a turkey flock in Indiana. Putative low pathogenic avian influenza (LPAI) viruses similar to A/turkey/Indiana/1573-2/2016 were subsequently isolated from 9 other turkey flocks in the area. There were no reports of human cases associated with this virus at the time of the IRAT scoring.

Summary: A risk assessment of this LPAI virus was conducted in July 2017. The overall IRAT risk assessment score for this virus falls into the low risk category (< 4). The summary average risk score for the virus to achieve sustained human-to-human transmission is in the low risk category (3.4). The summary average risk score for the virus to significantly impact public health if it were to achieve sustained human-to-human transmission was also in the low risk category (3.9).

Low pathogenic avian influenza (LPAI) H7N9 viruses were first reported from China in March 2013. These viruses were first scored using the IRAT in April 2013, and then annually in 2014, 2015, and 2016 with no change in overall risk scores. Between October 2016 and May 2017 evidence of two divergent lineages of these viruses was detected – the Pearl River Delta lineage and the Yangtze River Delta lineage. The IRAT was used to assess LPAI H7N9 [A/Hong Kong/125/2017], a representative of the Yangtze River Delta viruses.

Summary: A risk assessment of H7N9 [A/Hong Kong/125/2017] was conducted in May 2017. The overall IRAT risk assessment score for this virus falls into the moderate-high risk category and is similar to the scores for the previous H7N9 viruses. The summary average risk score for the virus to achieve sustained human-to-human transmission is in the moderate risk category (less than 7). The summary average risk score for the virus to significantly impact public health if it were to achieve sustained human-to-human transmission was in the moderate-high risk category (less than 8).

H7N9: Avian H7N9 [A/Shanghai/02/2013]

On 31 March 2013, the China Health and Family Planning Commission notified the World Health Organization (WHO) of three cases of human infection with influenza H7N9. As of August 2016, the WHO has received reports of 821 cases, 305 have died. This low pathogenic avian influenza virus was rescored most recently in April 2016 with no substantive change in risk scores since May 2013.

Summary: The summary average risk score for the virus to achieve sustained human-to-human transmission was in the moderate risk category (less than 7). The average risk score for the virus to significantly impact public health if it were to achieve sustained human-to-human transmission fell in the high-moderate risk range (less than 8).

H7N9: Low Pathogenic North American avian [A/chicken/Tennessee/17-007431-3/2017]

Surveillance conducted in March 2017 during the investigation of a highly pathogenic avian influenza (HPAI) A(H7N9) virus in commercial poultry in Tennessee revealed the contemporaneous presence of North American lineage low pathogenic avian influenza (LPAI) A(H7N9) virus in commercial and backyard poultry flocks in Tennessee and three other states. The outbreak in poultry appeared limited with no further detections in subsequent surveillance. There were no reports of human cases associated with this virus.

Summary: A risk assessment this North American lineage LPAI A(H7N9) virus was conducted in October 2017. The overall IRAT risk assessment score for this virus falls into the low risk category (< 4). The summary average risk score for the virus to achieve sustained human-to-human transmission was in the low risk category (score 3.1). The average risk score for the virus to significantly impact public health if it were to achieve sustained human-to-human transmission was between the low to low-moderate range (score 3.5). For a full report, click here[228 KB, 4 pages](https://www.cdc.gov/flu/pandemic-resources/pdf/cdc-irat-virus-lpai.pdf).

H7N9: High Pathogenic North American avian [A/chicken/Tennessee/17-007147-2/2017]

In March 2017, the U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) reported the detection of a highly pathogenic avian influenza (HPAI) A(H7N9) virus in 2 commercial poultry flocks in Tennessee. Full genome sequence analysis indicated that all eight gene segments of the virus were of North American wild bird lineage and genetically distinct from the lineage of influenza A(H7N9) viruses infecting poultry and humans in China since 2013. The outbreak investigation revealed that a related North American low pathogenic avian influenza A(H7N9) was circulating in poultry prior to the detection of the HPAI A(H7N9). There were no reports of human cases associated with this virus.

Summary: A risk assessment this North American lineage HPAI A(H7N9) virus was conducted in October 2017. The overall IRAT risk assessment score for this virus falls into the low risk category (< 4). The summary average risk score for the virus to achieve sustained human-to-human transmission is in the low risk category (2.8). The summary average risk score for the virus to significantly impact public health if it were to achieve sustained human-to-human transmission was also in the low risk category (3.5). For a full report, click here[225 KB, 4 pages](https://www.cdc.gov/flu/pandemic-resources/pdf/cdc-irat-virus-hpai.pdf).

H9N2: Avian H9N2 G1 lineage [A/Bangladesh/0994/2011]

Human infections with influenza AH9N2 virus have been reported sporadically, cases reportedly exhibited mild influenza-like illness. Historically these low pathogenic avian influenza viruses have been isolated from wild and domestic birds. In response to these reports, a risk assessment of this H9N2 influenza virus was conducted in 2014.

Summary: The summary average risk score for the virus to achieve sustained human-to-human transmission was in the moderate risk category (less than 6). The summary average risk score for the virus to significantly impact public health if it were to achieve sustained human-to-human transmission also fell in the moderate risk range (less than 6).

H10N8: Avian H10N8 [A/Jiangxi-Donghu/346/2013]

Two human infections with influenza A(H10N8) virus were reported by the China Health and Family Planning Commission in 2013 and 2014 (one each year). Both cases were hospitalized and one died. Historically low pathogenic avian influenza H10 and N8 viruses have been recovered from birds. A risk assessment of the H10N8 influenza was conducted in 2014.

Summary: The summary average risk score for the virus to achieve sustained human-to-human transmission was low-moderate (less than 5). The average risk score for the virus to significantly impact public health if it were to achieve sustained human-to-human transmission was in the moderate risk range (less than 7).

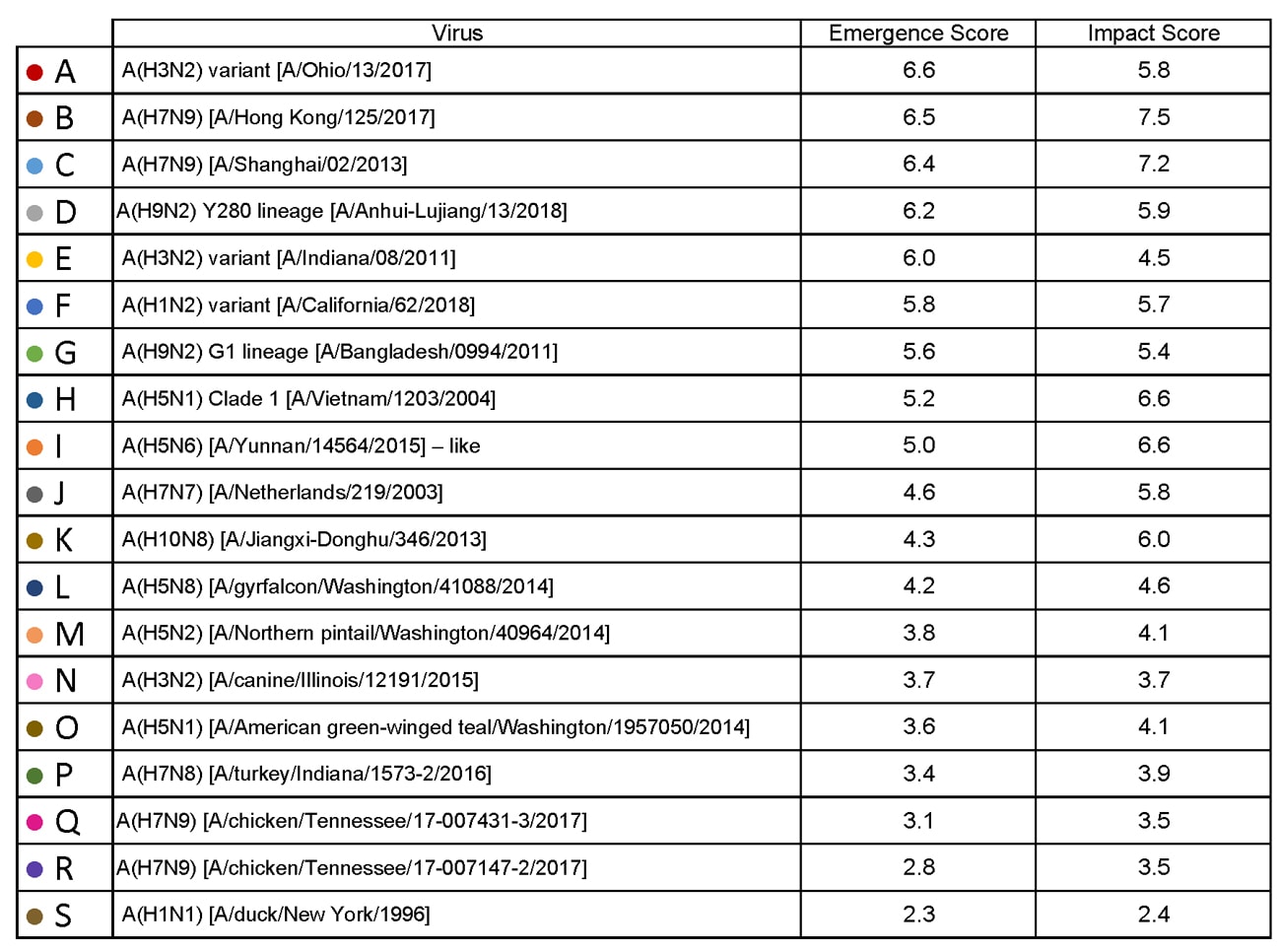

CDC has now confirmed 132 cases in 32 states tied to the use of kratom, an herbal alternative to opioids.

Saturday, April 7th, 2018What’s New?

- Forty-five more ill people from 19 states were added to this investigation since the last update on March 15, 2018.

- Three additional states have reported ill people: Connecticut, Iowa, and Idaho.

Highlights

- At this time, CDC recommends that people not consume any brand of kratom in any form because it could be contaminated with Salmonella.

- Kratom products from several companies have been recalled because they might be contaminated with Salmonella. The list of recalled kratom products is available on the U.S. Food and Drug Administration website.

- Kratom is also known as Thang, Kakuam, Thom, Ketom, and Biak.

- Kratom is a plant consumed for its stimulant effects and as an opioid substitute.

- CDC, public health and regulatory officials in several states, and the U.S. Food and Drug Administration are investigating a multistate outbreak of Salmonella infections.

- Epidemiologic and laboratory evidence indicates that kratom is the likely source of this multistate outbreak.

- No common brands or suppliers of kratom products have been identified at this time.

- Because no common source of Salmonella-contaminated kratom has been identified, CDC is recommending against consuming any kratom.

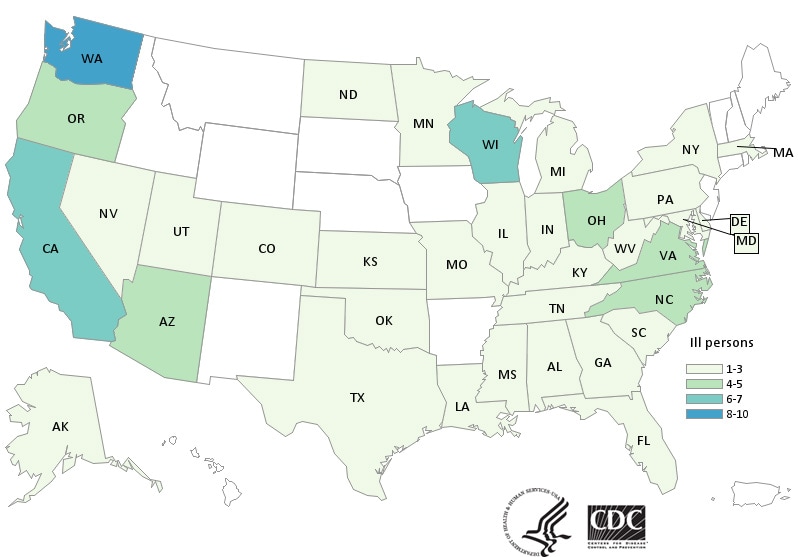

- A total of 132 people infected with outbreak strains of Salmonella I 4,[5],12:b:- (61), Salmonella Javiana (15), Salmonella Okatie (21), or Salmonella Thompson (35) have been reported from 38 states.

- Forty percent of ill people have been hospitalized, and no deaths have been reported.

- This investigation is ongoing. CDC will provide updates when more information is available.

A multistate Salmonella outbreak linked to kratom supplements has sickened 47 more people and expanded to 8 more states, raising the total to 87 cases from 35 states,

Tuesday, March 20th, 2018Multistate Outbreak of Salmonella I 4,[5],12:b:- Infections Linked to Kratom

Sunday, March 4th, 2018CDC is dramatically downsizing its epidemic prevention activities in 39 out of 49 countries because money is running out

Friday, February 2nd, 2018“…..The CDC plans to narrow its focus to 10 “priority countries,” starting in October 2019, the official said. They are India, Thailand and Vietnam in Asia; Jordan in the Middle East; Kenya, Uganda, Liberia, Nigeria and Senegal in Africa; and Guatemala in Central America.

Countries where the CDC is planning to scale back include some of the world’s hot spots for emerging infectious disease, such as China, Pakistan, Haiti, Rwanda and Congo……”

CDC plans to scale back or discontinue its work to prevent infectious-disease epidemics and other health threats in 39 foreign countries because it expects funding for the work to end

Saturday, January 20th, 2018“….The CDC currently works in 49 countries as part of an initiative called the global health security agenda, to prevent, detect and respond to dangerous infectious disease threats. It helps expand surveillance for new viruses and drug-resistant bacteria, modernize laboratories to detect dangerous pathogensand train workers who respond to epidemics.The package included $582 million in funds to work with countries around the world after the Ebola crisis in 2014 and 2015. But that funding runs out at the end of fiscal 2019……..[T]he CDC said it anticipates that if its funding situation remains the same, it will have to narrow activities to 10 “priority countries” starting in October 2019……..

The 10 countries where global health security activities will remain are India, Thailand, Vietnam, Kenya, Uganda, Liberia, Nigeria, Senegal, Jordan and Guatemala, according to the email—countries of strategic or regional importance for the CDC….”

January 7-13: Folic Acid Awareness week

Wednesday, January 10th, 2018Facts About Folic Acid

CDC urges women to take 400 mcg of folic acid every day, starting at least one month before getting pregnant, to help prevent major birth defects of the baby’s brain and spine.

About folic acid

Folic acid is a B vitamin. Our bodies use it to make new cells. Everyone needs folic acid.

Why folic acid is so important

Folic acid is very important because it can help prevent some major birth defects(https://www.cdc.gov/ncbddd/birthdefects/index.html) of the baby’s brain and spine (anencephaly(https://www.cdc.gov/ncbddd/birthdefects/anencephaly.html) and spina bifida(https://www.cdc.gov/ncbddd/spinabifida)).

How much folic acid a woman needs

400 micrograms (mcg) every day.

&amp;lt;div class=”noscript”&amp;gt;&amp;lt;a href=”//www.youtube-nocookie.com/embed/kPtCoBSmisE?autohide=0&amp;amp;amp;enablejsapi=1&amp;amp;amp;playerapiid=41053&amp;amp;amp;modestbranding=1&amp;amp;amp;rel=0&amp;amp;amp;origin=https://www.cdc.gov&amp;amp;amp;famp;wmode=opaque” target=”_blank”&amp;gt;Folic Acid and You: Your Healthy Pregnancy&amp;lt;/a&amp;gt;&amp;lt;/div&amp;gt;

When to start taking folic acid

For folic acid to help prevent some major birth defects, a woman needs to start taking it at least one month before she becomes pregnant and while she is pregnant.

Every woman needs folic acid every day, whether she’s planning to get pregnant or not, for the healthy new cells the body makes daily. Think about the skin, hair, and nails. These – and other parts of the body – make new cells each day.

How a woman can get enough folic acid

There are two easy ways to be sure to get enough folic acid each day:

- Take a vitamin that has folic acid in it every day.

- Most multivitamins sold in the United States have the amount of folic acid women need each day. Women can also choose to take a small pill (supplement) that has only folic acid in it each day.

- Multivitamins and folic acid pills can be found at most local pharmacy, grocery, or discount stores. Check the label to be sure it contains 100% of the daily value (DV) of folic acid, which is 400 micrograms (mcg).

- Eat a bowl of breakfast cereal that has 100% of the daily value of folic acid every day.

- Not every cereal has this amount. Check the label on the side of the box, and look for one that has “100%” next to folic acid.

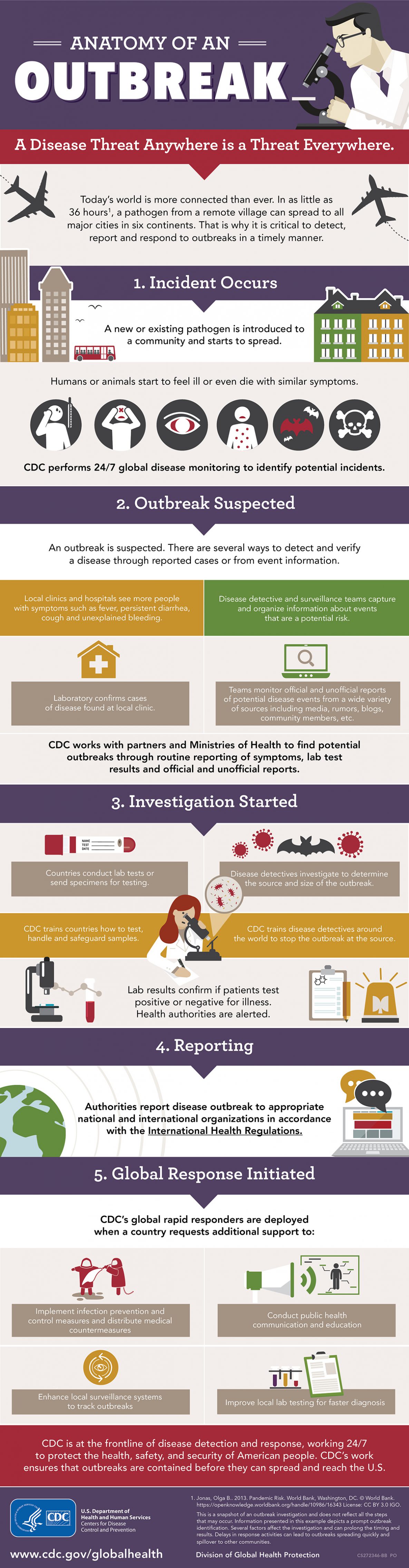

CDC :: Anatomy of an Outbreak: A Disease Threat Anywhere is a Threat Everywhere.

Monday, January 1st, 2018

NATOMY OF AN OUTBREAK

A Disease Threat Anywhere is a Threat Everywhere.

Today’s world is more connected than ever. In as little as 36 hours1, a pathogen from a remote village can spread to all major cities in six continents. That is why it is critical to detect, report and respond to outbreaks in a timely manner.

- Incident Occurs

A new or existing pathogen is introduced to a community and starts to spread.

Humans or animals start to feel ill or even die with similar symptoms.

CDC performs 24/7 global disease monitoring to identify potential incidents.

- Outbreak Suspected

An outbreak is suspected. There are several ways to detect and verify a disease through reported cases or from event information.

Local clinics and hospitals see more people with symptoms such as fever, persistent diarrhea, cough and unexplained bleeding.

Laboratory confirms cases of disease found at local clinic.

Disease detective and surveillance teams capture and organize information about events that are a potential risk.

Teams monitor official and unofficial reports of potential disease events from a wide variety of sources including media, rumors, blogs, community members, etc.

CDC works with partners and Ministries of Health to find potential outbreaks through routine reporting of symptoms, lab test results and official and unofficial reports.

- Investigation Started

Countries conduct lab tests or send specimens for testing.

CDC trains countries how to test, handle and safeguard samples.

Disease detectives investigate to determine the source and size of the outbreak.

CDC trains disease detectives around the world to stop the outbreak at the source.

Lab results confirm if patients test positive or negative for illness.

Health authorities are alerted.

- Reporting

Authorities report disease outbreak to appropriate national and international organizations in accordance with the International Health Regulations.

- Global Response Initiated

CDC’s global rapid responders are deployed when a country requests additional support to:

Implement infection prevention and control measures and distribute medical countermeasures

Conduct public health communication and education

Enhance local surveillance systems to track outbreaks

Improve local lab testing for faster diagnosis

CDC is at the frontline of disease detection and response, working 24/7 to protect the health, safety, and security of American people. CDC’s work

ensures that outbreaks are contained before they can spread and reach the U.S.

- Jonas, Olga B.. 2013. Pandemic Risk. World Bank, Washington, DC. © World Bank. https://openknowledge.worldbank.org/handle/10986/16343 License: CC BY 3.0 IGO.

This is a snapshot of an outbreak investigation and does not reflect all the steps that may occur. Information presented in this example depicts a prompt outbreak identification. Several factors affect the investigation and can prolong the timing and results. Delays in response activities can lead to outbreaks spreading quickly and spillover to other communities.

![People infected with the outbreak strain of Salmonella I 4,[5],12:b:-, by state of residence, as of February 28, 2018](https://www.cdc.gov/salmonella/kratom-02-18/images/map/big-map-2-28-18.jpg)

![People infected with the outbreak strain of Salmonella I 4,[5],12:b:- by date of illness onset as of February 28, 2018*](https://www.cdc.gov/salmonella/kratom-02-18/images/epi-curve/big-epi-2-28-18.jpg)