Archive for the ‘CDC’ Category

October 15: Global Handwashing Day

Saturday, October 15th, 2016

Keeping your hands clean is one of the most important steps you can take to avoid getting sick and spreading germs to the people around you. Many diseases and conditions are spread by not cleaning your hands properly. Here are five important things you might not know about washing your hands and why it matters.

- Soap is key. Washing your hands with soap removes germs much more effectively than using water alone.[i] The compounds, called surfactants, in soap help remove soil and microbes from your skin. You also tend to scrub your hands more thoroughly when you use soap, which also helps to removes germs.[ii]

- It takes longer than you might think. The optimal length of time to wash your hands depends on many factors, including the type and amount of soil on your hands. Evidence suggests that washing your hands for about 15–30 seconds removes more germs than washing for shorter periods.[iii] CDC recommends washing your hands for about 20 seconds, or the time it takes to hum the “Happy Birthday” song twice from beginning to end.

- It’s all about technique. Make sure to clean the spots on your hands that people miss most frequently. Pay particular attention to the backs of your hands, in between your fingers, and under your nails. Lathering and scrubbing your hands creates friction, which helps to remove dirt, grease, and germs from your skin.

- Don’t forget to dry. Germs can be transferred more easily to and from wet hands, so you should dry your hands after washing.[iv] Studies suggest that using a clean towel or letting your hands air dry are the best methods to get your hands dry.[v],[vi],[vii]

- Hand sanitizer is an option. If you can’t get to a sink to wash your hands with soap and water, use an alcohol-based hand sanitizer that contains at least 60% alcohol. Make sure you use enough to cover all surfaces of your hands. Do not rinse or wipe off the hand sanitizer before it is dry.[viii]

Note: Hand sanitizer may not kill all germs, especially if your hands are visibly dirty or greasy,[ix] so it is important to wash hands with soap and water as soon as possible after using hand sanitizer.

Why it Matters

Remember, clean hands save lives. Diarrheal diseases and pneumonia are the top two killers of young children around the world, killing 1.8 million children under the age of five every year.[x] Among young children, handwashing with soap prevents 1 out of every 3 diarrheal illnesses [xi] and 1 out of 5 respiratory infections like pneumonia worldwide.[xii],[xiii]

October 15th is Global Handwashing Day

Handwashing is for everyone…everywhere. Global Handwashing Day is an opportunity to support a global and local culture of handwashing with soap and water, shine a spotlight on the state of handwashing in each country, and raise awareness about the benefits of washing your hands with soap. Although people around the world clean their hands with water, very few use soap to wash their hands because soap and water for handwashing might be less accessible in developing countries.

Get Involved!

- Organize or participate in a handwashing event in your school or community. Find educational resources and materials and planning tools.

- Celebrate virtually on Twitter and Facebook. Look for and use the hashtag #GlobalHandwashingDay, download pre-drafted educational social media messages, and share CDC’s Global Handwashing Day digital button.

- Make sure you and your family know when and how to wash your hands properly.

- Share the science behind handwashing.

References

[i] Burton M, Cobb E, Donachie P, Judah G, Curtis V, Schmidt WP. The effect of handwashing with water or soap on bacterial contamination of hands. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2011 Jan;8(1):97-104.

[ii] Burton M, Cobb E, Donachie P, Judah G, Curtis V, Schmidt WP. The effect of handwashing with water or soap on bacterial contamination of hands. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2011 Jan;8(1):97-104.

[iii] Jensen D, Schaffner D, Danyluk M, Harris L. Efficacy of handwashing duration and drying methods. Int Assn Food Prot. 2012 July.

[iv] Patrick DR, Findon G, Miller TE. Residual moisture determines the level of touch-contact-associated bacterial transfer following hand washing. Epidemiol Infect. 1997 Dec;119(3):319-25.

[v] Gustafson DR, Vetter EA, Larson DR, Ilstrup DM, Maker MD, Thompson RL, Cockerill FR 3rd. Effects of 4 hand-drying methods for removing bacteria from washed hands: a randomized trial. Mayo Clin Proc. 2000 Jul;75(7):705-8.

[vi] Huang C, Ma W, Stack S. The hygienic efficacy of different hand-drying methods: a review of the evidence. Mayo Clin Proc. 2012 Aug;87(8):791-8.

[vii] Jensen D, Schaffner D, Danyluk M, Harris L. Efficacy of handwashing duration and drying methods. Int Assn Food Prot Annual Meeting. 2012 July 22-25.

[viii] Widmer, A. F., Dangel, M., & RN. (2007). Introducing alcohol-based hand rub for hand hygiene: the critical need for training. Infection Control and Hospital Epidemiology, 28(1), 50-54.

[ix] Pickering AJ, Davis J, Boehm AB. Efficacy of alcohol-based hand sanitizer on hands soiled with dirt and cooking oil. J Water Health. 2011 Sep;9(3):429-33.

[x] Liu L, Johnson HL, Cousens S, Perin J, Scott S, Lawn JE, Rudan I, Campbell H, Cibulskis R, Li M, Mathers C, Black RE; Child Health Epidemiology Reference Group of WHO and UNICEF. Global, regional, and national causes of child mortality: an updated systematic analysis for 2010 with time trends since 2000. Lancet. 2012 Jun 9;379(9832):2151-61.

[xi] Ejemot RI, Ehiri JE, Meremikwu MM, Critchley JA. Hand washing for preventing diarrhoea. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2008;1:CD004265.

[xii] Rabie T and Curtis V. Handwashing and risk of respiratory infections: a quantitative systematic review.Trop Med Int Health. 2006 Mar;11(3):258-67.

[xiii] Aiello AE, Coulborn RM, Perez V, Larson EL. Effect of hand hygiene on infectious disease risk in the community setting: a meta-analysis. Am J Public Health. 2008;98(8):1372-81.

Posted on October 14, 2016 by

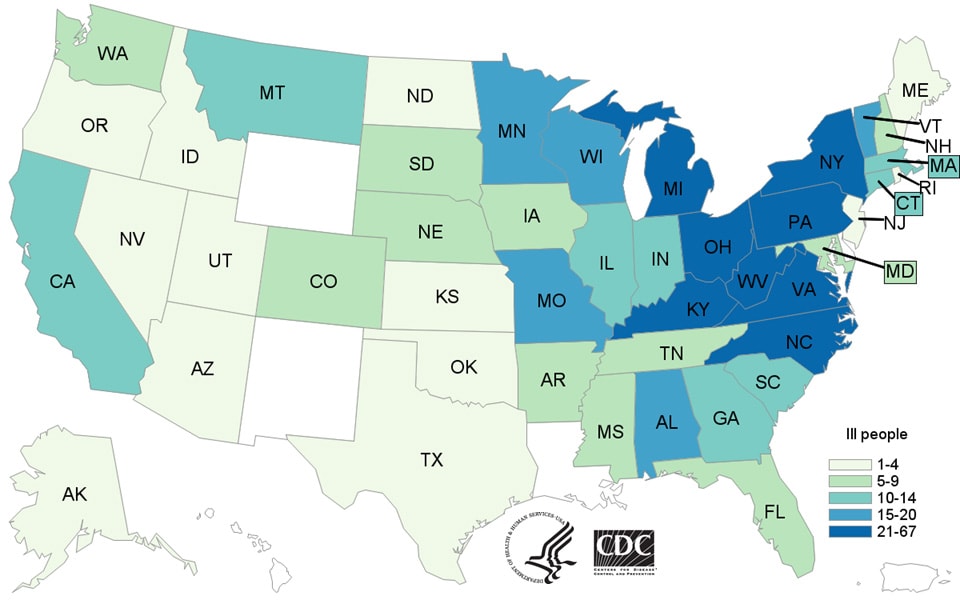

From January 1 to August 31, 2016, a total of 50 people in 24 states across the country were confirmed to have AFM (Acute flaccid myelitis)

Wednesday, October 5th, 2016AFM in the United States

Acute flaccid myelitis (AFM) is a rare illness that anyone can get. It affects a person’s nervous system, specifically the spinal cord. AFM can result from a variety of causes, including viral infections.

Beginning in August 2014, CDC received an increase in reports of people across the United States with AFM for which no cause could be found. Since then, CDC has been actively investigating this illness. We continue to receive reports of sporadic cases of AFM. From January 1 to August 31, 2016, a total of 50 people in 24 states across the country were confirmed to have AFM.

Updated October 3, 2016

^ Cases reported as of September 30, 2016. The case counts are subject to change. CDC updates the case counts monthly with a one month lag to allow the time needed for case review.

* The data shown from August 2014 to July 2015 are based on the AFM investigation case definition: onset of acute limb weakness on or after August 1, 2014, and a magnetic resonance image (MRI) showing a spinal cord lesion largely restricted to gray matter in a patient age ≤21 years.

† The data shown from August 2015 to present are based on a revised AFM case definition adopted by CSTE: acute onset of focal limb weakness and an MRI showing spinal cord lesion largely restricted to gray matter and spanning one or more spinal segments, regardless of age.

For more information on AFM case definitions, visit the Case Definitions(https://www.cdc.gov/acute-flaccid-myelitis/hcp/case-definition.html) page.

What This Graph Shows

- From January 1 to August 31, 2016, 50 people were confirmed to have AFM. (Note: The cases occurred in 24 states across the U.S.)

- In 2015, 21 people were confirmed to have AFM. (Note: The cases occurred in 16 states across the U.S.)

- From August to December 2014, 120 people were confirmed to have AFM. (Note: The cases occurred in 34 states across the U.S.)

- The case counts represent only those cases reported to and confirmed by CDC.

- There has been an increase in reports of confirmed AFM cases in 2016 compared with 2015 (21 cases in 16 states).

The graph shows reports of cases confirmed by CDC as of September 30, 2016.

It is currently difficult to interpret trends of the AFM data since reporting only started in 2014 and is voluntary in most states. Also, since AFM reporting is relatively new, there may initially be more variability in the data from year to year making it difficult to interpret or compare case counts between years. One possible reason for the differences in annual reporting is more awareness among and reporting by healthcare providers and health departments.

To protect patient confidentiality, CDC is not specifying the states with confirmed AFM cases. We defer to the states to release information as they choose.

Number of confirmed AFM cases by year of illness onset, 2014-2016

| Year | Number confirmed cases | Number of states reporting confirmed cases |

|---|---|---|

| 2014 (Aug-Dec) | 120 | 34 |

| 2015 | 21 | 16 |

| 2016* (Jan-Aug) | 50 | 24 |

*The case counts are subject to change.

What We Know

What we know about the AFM cases reported since August 2014:

- The patients’ symptoms have been most similar to those caused by certain viruses, including poliovirus, non-polio enteroviruses, adenoviruses, and West Nile virus. See a list of viruses associated with AFM(https://www.cdc.gov/acute-flaccid-myelitis/about-afm.html#germs).

- Enteroviruses can cause neurologic illness, including meningitis. However, more severe disease, such as encephalitis and AFM, is not common. Rather, they most commonly cause mild illness.

- CDC has tested many different specimens from the patients for a wide range of pathogens (germs) that can cause AFM. To date, we have not consistently detected a pathogen (germ) in the patients’ spinal fluid; a pathogen detected in the spinal fluid would be good evidence to indicate the cause of AFM since this illness affects the spinal cord.

- The increase in AFM cases in 2014 coincided with a national outbreak of severe respiratory illness among people caused by enterovirus D68 (EV-D68). Among the people with AFM, CDC did not consistently detect EV-D68 in the specimens collected from them. In 2015 there were no cases of EV-D68 detected and so far in 2016, only limited sporadic cases of EV-D68(https://www.cdc.gov/non-polio-enterovirus/about/ev-d68.html) have been detected in the United States.

What We Don’t Know

What we don’t know about the AFM cases reported since August 2014:

- Despite extensive testing, CDC does not yet know the cause of the AFM cases.

- It is unclear what pathogen (germ) or immune response is causing the disruption of signals sent from the nervous system to the muscles causing weakness in the arms and legs.

- CDC has not yet determined who is at higher risk for developing AFM, or the reasons why they may be at higher risk.

See Prevention(https://www.cdc.gov/acute-flaccid-myelitis/about-afm.html#prevention) for information about how to protect your family from viral infections that may cause AFM

What CDC Is Doing

CDC is actively investigating the AFM cases and monitoring disease activity. We are working closely with healthcare providers and state and local health departments to increase awareness and reporting for AFM, and investigate the AFM cases, risk factors, and possible causes of this illness.

CDC activities include:

- encouraging healthcare providers to be vigilant for AFM among their patients, and to report suspected cases to their health departments

- verifying reports of suspected AFM cases submitted by health departments using a case definition adopted by the Council of State and Territorial Epidemiologists (CSTE)

- testing specimens, including stool, blood, respiratory and cerebrospinal fluid, from people confirmed to have AFM

- working with clinicians and state and local health departments to investigate and better understand the AFM cases, including potential causes and how often the illness occurs

- providing new and updated information to clinicians, health departments, policymakers, the public, and partners in various formats, such as the Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report, the AFM website, and CDC social media

- pursuing an approach that uses multiple research methods to further explore the potential association of AFM with possible causes as well as risk factors for AFM. This includes collaborating with several medical institutions to review MRI scans of people from the past 10 years to determine how many AFM cases occurred before 2014.

For more information, see COCA Clinical Reminder (August 27, 2015) – Notice to Clinicians: Continued Vigilance Urged for Cases of Acute Flaccid Myelitis.

The 2014 investigation summary is available here: Acute Flaccid Myelitis in the United States—August – December 2014: Results of Nation-Wide Surveillance.

October: National Preparedness Month: Radiation Emergencies

Monday, October 3rd, 2016National Preparedness Month: Radiation Emergencies

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) sent this bulletin at 09/30/2016 02:18 PM EDT

National Preparedness Month: Radiation Emergencies

Protect Yourself and Your Family in a Radiation Emergency

Get Inside. Stay Inside. Stay Tuned.

In support of National Preparedness Month in September, CDC’s Radiation Studies Branch (RSB) is highlighting information on the Radiation Emergencies website to help the public, public health, and medical communities prepare for a radiation emergency.

The focus for this month is Radiation Emergencies: Protect Yourself, Your Family and Your Community. A different topic is highlighted throughout the month:

- Preparedness Starts in Your Community–Talk with your family and friends about what to do in a radiation emergency.

- Community Preparedness is the Key to Your Health and Safety—Preparedness starts at home, in your community, workplaces and schools. Ask questions about sheltering in place and other actions you can take in a radiation emergency.

- Protect Yourself, Your Family and Your Community—Work together with community members to promote awareness of available resources for radiation emergencies.

Be Prepared for a Radiation Emergency

What can you do before a radiation emergency happens so that you are prepared? At home, put together an emergency kit that would be appropriate for any emergency. A battery-powered or hand crank emergency radio, preferably a National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) weather radio is important to have for any emergency situation.

Check with your community leaders, child’s school, the nursing home of a family member, and your employer to see what their plans are for dealing with a radiation emergency.

School District Crisis Preparedness, Response, and Recovery Plans — United States, 2012

Thursday, September 22nd, 2016KidSchoolDisasterPrep: MMWR Document

Weekly / September 16, 2016 / 65(36);949–953

Brenda Silverman, PhD1; Brenda Chen, MBBS1; Nancy Brener, PhD2; Judy Kruger, PhD1; Nevin Krishna, MS, MPH1; Paul Renard Jr, MS1; Sandra Romero-Steiner, PhD3; Rachel Nonkin Avchen, PhD1

Summary

What is already known about this topic?Children represent nearly one fourth of the U.S. population, have unique vulnerabilities, and might be in a school setting, separated from families, when a disaster occurs. The U.S. Department of Education recommends that schools develop and exercise crisis preparedness plans in collaboration with community partners.

What is added by this report?Data from the 2012 School Health Policies and Practices Study indicated that 79.9% of school districts required schools to have a comprehensive plan that includes provisions for students and staff members with special needs, whereas 67.8% to 69.3% of districts required plans that addressed family reunification procedures, procedures for responding to pandemic influenza or other infectious disease outbreaks, and provision of mental health services for students, faculty, and staff members, after a crisis. On average, urban districts required schools to include more of the four selected topics in their plans than nonurban districts. Across all districts, >90% collaborated on plans with staff members from individual schools within the district, local fire departments, and local law enforcement agencies.

What are the implications for public health practice?The deficiencies found in some census regions show a need to strengthen school district–based disaster preparedness planning. These deficiencies need to be addressed to meet the four Healthy People 2020 preparedness objectives (PREP-5).

The unique characteristics of children dictate the need for school-based all-hazards response plans during natural disasters, emerging infectious diseases, and terrorism (1–3). Schools are a critical community institution serving a vulnerable population that must be accounted for in public health preparedness plans; prepared schools are adopting policies and plans for crisis preparedness, response, and recovery (2–4). The importance of having such plans in place is underscored by the development of a new Healthy People 2020 objective (PREP-5) to “increase the percentage of school districts that require schools to include specific topics in their crisis preparedness, response, and recovery plans” (5). Because decisions about such plans are usually made at the school district level, it is important to examine district-level policies and practices. Although previous reports have provided national estimates of the percentage of districts with policies and practices in place (6), these estimates have not been analyzed by U.S. Census region* and urbanicity.† Using data from the 2012 School Health Policies and Practices Study (SHPPS), this report examines policies and practices related to school district preparedness, response, and recovery. In general, districts in the Midwest were less likely to require schools to include specific topics in their crisis preparedness plans than districts in the Northeast and South. Urban districts tended to be more likely than nonurban districts to require specific topics in school preparedness plans. Southern districts tended to be more likely than districts in other regions to engage with partners when developing plans. No differences in district collaboration (with the exception of local fire department engagement) were observed by level of urbanicity. School-based preparedness planning needs to be coordinated with interdisciplinary community partners to achieve Healthy People 2020 PREP-5 objectives for this vulnerable population.

SHPPS is a national survey conducted every 6 years by CDC to assess school health policies and practices at state, district, school, and classroom levels. This report uses school district–level data from the 2012 survey (6). A two-stage sample design was used to generate a nationally representative sample of public school districts in the United States. Seven district-level questionnaires (each assessing different aspects of school policies and practices) were administered in each sampled district; this report provides results from the healthy and safe school environment questionnaire. Respondents were asked whether their school district required schools to have a comprehensive plan to address crisis preparedness, response, and recovery that included four specific topics identified in PREP-5: family reunification procedures, procedures for responding to pandemic influenza or other infectious disease outbreaks, provisions for students and staff members with special needs, and provision of mental health services for students and staff members after a crisis. Respondents also were asked whether the district collaborated with specified categories of partners (e.g., local fire department or local mental health or social services agency) in developing crisis preparedness plans.

A single respondent identified by the district as the most knowledgeable on the topic responded to each questionnaire module. During October 2011–August 2012, respondents completed questionnaires via a secure data collection website or paper-based questionnaires. Among eligible districts, 697 (66.5%) completed the healthy and safe school environment questionnaire. Additional data regarding SHPPS methods are available online (6). Data were weighted to provide national estimates and analyzed using statistical software that accounted for the complex sample design. School districts were categorized by geographic location into one of the four U.S. Census regions (Midwest, Northeast, South, and West) and by level of urbanicity (urban or nonurban). Prevalence estimates and 95% confidence intervals were computed for all point estimates. Significant differences were evaluated by census region and urbanicity by t-test, with significance set at p<0.05.

District requirements for school plans varied by specific topic and region, ranging from 87.8% in the South for provisions for students and staff members with special needs to 57.9% in the Midwest for procedures for responding to pandemic influenza or other infectious disease outbreaks (Table 1). Overall, 79.9% of school districts required provisions for students and staff members with special needs; 67.8% required plans that addressed family reunification procedures, 69.0% required procedures for responding to pandemic influenza or other infectious disease outbreaks, and 69.3% required plans for provision of mental health services for students, faculty, and staff members after a crisis. For all four of the topics, the percentage of school districts requiring schools to address the topic was lowest in the Midwest.

By urbanicity, on average, urban districts required schools to include more of the four topics in their preparedness plans than did nonurban districts (3.1 versus 2.7 specific topics, p<0.05). Urban districts also were significantly (p<0.05) more likely than nonurban districts to require schools to include family reunification, provisions for students and staff members with special needs, and provision of mental health services in their plans (Table 1).

Analysis of responses regarding district collaboration with community partners found differences in practices for preparedness planning by census region, although only one significant difference was found by urbanicity (Table 2). Across all districts, >90% worked with 1) staff members from individual schools within the district, 2) local fire departments, and 3) local law enforcement agencies. In contrast, 16.6% of districts (range = 12.0%–20.8%) worked with a local public transportation department§ (Table 2).

Discussion

Children represent approximately one fourth of the U.S. population and are separated from their caregivers while attending school. They have unique physiological, psychological, and developmental attributes that make them at heightened risk during disasters (1–3). Particular challenges for school-based preparedness are planning for children with special needs (e.g., disabilities or functional or medical needs), chronic conditions, or limited English proficiency (1,2,4,7). Effective readiness can be hampered by compartmentalized planning that overlooks the unique vulnerabilities of children in and following public health disasters (8). Broader community participation in school-based disaster planning can ensure that relevant stakeholders have a common framework and understanding to support response and recovery following a disaster.

Although SHPPS found that more than two thirds of districts require schools to include specified topics in their crisis plans, these requirements do not necessarily exist at the state level. A 2014 National Report Card evaluated state-level standards for preparedness planning for children and found that only 29 states met the basic standards for safety of children during an event (9). However, the National Report Card focused primarily on disaster planning standards for children in child care facilities with only one standard specific to K-12. A state level approach to disaster preparedness planning is needed for both child care facilities and schools.

The findings in this report are subject to at least three limitations. First, the “yes or no” responses do not provide insight into the relevance of the specific topics in the preparedness plan or whether plans were exercised or evaluated to identify areas for improvement. Second, SHPPS data are collected every 6 years, and the most recent district data are from 2012. It is possible that some districts have updated their policies and practices related to preparedness since the data were collected. Finally, SHPPS data are self-reported and as such there might be opportunity for misclassification because of respondent interpretation of a particular question.

The U.S. Department of Education’s Practical Information on Crisis Planning: a Guide for Schools and Communities recommends that school crisis plans be developed in partnership with other community stakeholders (4). In this report, percentages of districts collaborating with school staff members and law enforcement, fire department, and emergency medical services were high across all census regions and levels of urbanicity, although other partnerships need improvement. The American Academy of Pediatrics suggests that additional efforts are needed to address deficiencies in partner engagement for school disaster planning and to address the unique vulnerabilities of children (3). School-based and community-based preparedness planning, training, exercises, and drills to improve emergency response, recovery, and overall community resilience are needed (7).

National and district-specific information on school crisis preparedness planning is required to identify and address critical gaps in preparedness, response, and recovery policies and plans for children. Findings from this report can strengthen school and community preparedness through multi-organizational, transdisciplinary partnerships engaged in preparedness planning (7). Disaster planning is a shared responsibility (2). The Children and Youth Task Force, Office of Human Services Emergency Preparedness and Response, is promoting a coordinated planning approach involving governmental and nongovernmental organizations and health care providers to improve outcomes and minimize the consequences of disasters on this vulnerable population (7).

Acknowledgments

Tim McManus, MS, Denise Bradford, MS, Division of Adolescent and School Health, National Center for HIV/AIDS, Viral Hepatitis, STD, and TB Prevention, CDC.

Corresponding author: Brenda Silverman, bsilverman@cdc.gov, 404-639-4342.

References

- Bartenfeld MT, Peacock G, Griese SE. Public health emergency planning for children in chemical, biological, radiological, and nuclear (CBRN) disasters. Biosecur Bioterror 2014;12:201–7. CrossRef PubMed

- National Commission on Children and Disasters. 2010 report to the president and Congress. AHRQ Publication No. 10-M037. Rockville, MD: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality; 2010.

- Council on School Health. Disaster planning for schools. Pediatrics 2008;122:895–901. CrossRef PubMed

- US Department of Education, Office of Safe and Drug-free Schools. Practical information on crisis planning: a guide for schools and communities, 2007. Washington, DC: US Department of Education; 2007. http://www2.ed.gov/admins/lead/safety/emergencyplan/crisisplanning.pdf

- US Department of Health and Human Services. Healthy people 2020. Washington, DC: US Department of Health and Human Services; 2016. https://www.healthypeople.gov/2020/topics-objectives/topic/preparedness/objectives

- CDC. Results from the School Health Policies and Practices Study 2012. Atlanta, GA: US Department of Health and Human Services, CDC; 2013. http://www.cdc.gov/healthyyouth/shpps/2012/pdf/shpps-results_2012.pdf

- US Administration for Children & Families, Office of Human Services Emergency Preparedness and Response. Children and Youth Task Force in Disasters: guidelines for development. 2013. http://www.acf.hhs.gov/sites/default/files/ohsepr/childrens_task_force_development_web_0.pdf

- Hinton CF, Griese SE, Anderson MR, et al. CDC grand rounds: addressing preparedness challenges for children in public health emergencies. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2015;64:972–4. CrossRef PubMed

- Save the Children. 2014 national report card on protecting children in disasters. Fairfield, CT: Save the Children; 2014. http://www.savethechildren.org/atf/cf/%7B9def2ebe-10ae-432c-9bd0-df91d2eba74a%7D/SC-2014_disasterreport.pdf

* https://www.census.gov/geo/reference/gtc/gtc_census_divreg.html.

† http://www.census.gov/geo/reference/urban-rural.html.

§ Sixty two percent of districts did not have public transportation departments.

TABLE 1. Percentage of school districts that require schools to have a comprehensive plan to address crisis preparedness, response, and recovery* that includes specific topics, by U.S. Census region and urbanicity — School Health Policies and Practices Study, United States, 2012

TABLE 1. Percentage of school districts that require schools to have a comprehensive plan to address crisis preparedness, response, and recovery* that includes specific topics, by U.S. Census region and urbanicity — School Health Policies and Practices Study, United States, 2012

| Specific topic | Census region† % (95% CI) | Urbanicity % (95% CI) | Total % (95% CI) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Midwest | Northeast | South | West | Urban | Nonurban | ||

| Family reunification procedures | 60.2§ (52.8–67.3) | 72.0¶ (62.3–80.0) | 71.6 (63.7–78.4) | 73.6** (63.1–82.1) | 78.0†† (71.5–83.4) | 61.5 (55.8–66.8) | 67.8 (63.5–71.9) |

| Procedures for responding to pandemic influenza or other infectious disease outbreaks | 57.9§ (50.2–65.3) | 75.2¶ (67.7–81.5) | 79.4 (72.5–84.9) | 68.5 (56.3–78.6) | 72.9 (66.1–78.8) | 66.5 (60.6–71.8) | 69.0 (64.7–73.1) |

| Provisions for students and staff members with special needs | 72.2§ (64.3–79.0) | 87.6¶ (80.9–92.1) | 87.8§§ (82.4–91.7) | 73.0¶¶ (63.9–80.5) | 85.8†† (80.6–89.7) | 76.3 (70.8–81.1) | 79.9 (76.0–83.3) |

| Provision of mental health services for students, faculty, and staff members after a crisis occurred*** | 60.1§ (52.7–67.1) | 80.4¶ (72.6–86.4) | 72.7 (65.7–78.6) | 71.6 (60.7–80.4) | 77.1†† (70.6–82.5) | 64.4 (59.0–69.4) | 69.3 (65.2–73.2) |

Abbreviation: CI = confidence interval.

* In the event of a natural disaster or other emergency or crisis situation.

† https://www.census.gov/geo/reference/gtc/gtc_census_divreg.html.

§ Significant difference (p<0.05) between Midwest and South districts.

¶ Significant difference (p<0.05) between Northeast and Midwest districts.

** Significant difference (p<0.05) between West and Midwest districts.

†† Significant difference (p<0.05) between urban and nonurban districts.

§§ Significant difference (p<0.05) between South and West districts.

¶¶ Significant difference (p<0.05) between West and Northeast districts.

*** For example, to treat post-traumatic stress disorder.

TABLE 2. Percentage of school districts that collaborated with school or community partners to develop preparedness, response, and recovery plans,* by planning partner type, U.S. Census region, and urbanicity — School Health Policies and Practices Study, United States, 2012

TABLE 2. Percentage of school districts that collaborated with school or community partners to develop preparedness, response, and recovery plans,* by planning partner type, U.S. Census region, and urbanicity — School Health Policies and Practices Study, United States, 2012

| Partners engaged | Census region† % (95% CI) | Urbanicity % (95% CI) | Total§ % (95% CI) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Midwest | Northeast | South | West | Urban | Nonurban | ||

| Staff members from individual schools within district | 93.0 (88.3–95.9) | 97.4 (92.3–99.1) | 96.9 (92.7–98.7) | 95.7 (87.6–98.6) | 97.1 (94.0–98.6) | 94.3 (91.1–96.5) | 95.4 (93.2–96.9) |

| Students or their families | 33.5¶ (27.4–40.1) | 47.0** (36.7–57.6) | 50.9 (43.5–58.2) | 43.8 (34.2–53.8) | 42.8 (36.2–49.8) | 43.0 (39.9–48.3) | 42.8 (38.7–46.9) |

| Local fire department | 90.9 (86.2–94.1) | 95.8 (90.3–98.2) | 91.7 (86.4–95.0) | 89.3 (80.8–94.4) | 94.7†† (90.8–97.0) | 90.1 (86.6–92.7) | 91.9 (89.4–93.9) |

| Local law enforcement agency | 93.8 (89.4–96.5) | 100**, §§ (100–100) | 94.0 (89.0–96.8) | 91.7¶¶ (83.1–96.1) | 96.7 (93.5–98.3) | 93.7 (90.4–95.9) | 94.8 (92.6–96.4) |

| Local emergency medical services | 80.0 (73.6–85.2) | 86.0 (78.4–91.2) | 87.4 (81.0–91.9) | 75.6 (63.2–84.8) | 82.3 (76.0–87.2) | 83.2 (78.6–86.9) | 82.8 (79.2–85.9) |

| Local public transportation department | 12.0¶ (8.1–17.4) | 20.6 (13.4–30.4) | 20.8 (15.5–27.4) | 13.7 (8.2–22.1) | 20.7 (15.4–27.2) | 14.0 (10.7–18.2) | 16.6 (13.7–20.0) |

| Local health department | 62.4 (55.4–69.1) | 69.1 (58.9–77.8) | 69.1 (61.5–75.7) | 60.9 (49.5–71.3) | 68.9 (61.9–75.2) | 63.5 (58.1–68.7) | 65.6 (61.3–69.6) |

| Local mental health or social services agency | 41.0 (34.5–47.9) | 51.8 (43.3–60.2) | 48.5 (40.7–56.4) | 46.1 (34.3–58.4) | 49.9 (43.1–56.7) | 43.8 (38.4–49.3) | 46.1 (41.9–50.4) |

| Local hospital | 39.7 (32.5–47.3) | 36.7§§ (27.6–46.8) | 50.3*** (42.4–58.2) | 32.1 (23.3–42.3) | 42.8 (35.7–50.1) | 40.1 (34.8–45.7) | 41.2 (36.9–45.6) |

| Local homeland security office or emergency management agency | 36.9¶ (29.8–44.6) | 51.6** (41.9–61.3) | 58.0*** (49.6–66.0) | 29.4¶¶ (20.7–39.8) | 49.2 (42.2–56.2) | 41.8 (36.0–47.9) | 45.1 (40.6–49.7) |

| Other community members | 61.4¶ (54.5–67.9) | 70.8 (61.6–78.5) | 76.7*** (69.0–83.0) | 58.6 (47.6–68.9) | 66.1 (59.5–72.2) | 67.7 (62.2–72.7) | 67.4 (63.2–71.3) |

Abbreviation: CI = confidence interval.

*Among districts that had a preparedness plan or required schools to have a plan.

† https://www.census.gov/geo/reference/gtc/gtc_census_divreg.html.

§Total refers to the total number of districts that responded to the evaluated question on the healthy and safe school environment module. Districts with missing data were not included in the denominator.

¶ Significant difference (p<0.05) between Midwest and South districts.

** Significant difference (p<0.05) between Northeast and Midwest districts.

†† Significant difference (p<0.05) between urban and nonurban districts.

§§ Significant difference (p<0.05) between Northeast and South districts.

¶¶ Significant difference (p<0.05) between West and Northeast districts.

*** Significant difference (p<0.05) between South and West districts.

Suggested citation for this article: Silverman B, Chen B, Brener N, et al. School District Crisis Preparedness, Response, and Recovery Plans — United States, 2012. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2016;65:949–953. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.15585/mmwr.mm6536a2.

Outcomes of Pregnancies with Laboratory Evidence of Possible Zika Virus Infection in the United States, 2016

Monday, July 25th, 2016Outcomes of Pregnancies with Laboratory Evidence of Possible Zika Virus Infection in the United States, 2016

Pregnancy Outcomes in the United States and the District of Columbia

Liveborn infants with birth defects*

12

Includes aggregated data reported to the US Zika Pregnancy Registry as of July 14, 2016

Pregnancy losses with birth defects**

6

Includes aggregated data reported to the US Zika Pregnancy Registry as of July 14, 2016

Pregnancy Outcomes in the United States Territories

Liveborn infants with birth defects*

0

Includes aggregated data from the US territories reported to the US Zika Pregnancy Registry and data from Puerto Rico reported to the Zika Active Pregnancy Surveillance System as of July 14, 2016

Pregnancy losses with birth defects**

1

Includes aggregated data from the US territories reported to the US Zika Pregnancy Registry and data from Puerto Rico reported to the Zika Active Pregnancy Surveillance System as of July 14, 2016

What these numbers show

- These numbers reflect poor outcomes among pregnancies with laboratory evidence of possible Zika virus infection reported to the US Zika Pregnancy Registry.

- The number of live-born infants and pregnancy losses with birth defects are combined for the 50 US states, the District of Columbia, and the US territories. To protect the privacy of the women and children affected by Zika, CDC is not reporting individual state, tribal, territorial or jurisdictional level data.

- The poor birth outcomes reported include those that have been detected in infants infected with Zika before or during birth, including microcephaly, calcium deposits in the brain indicating possible brain damage, excess fluid in the brain cavities and surrounding the brain, absent or poorly formed brain structures, abnormal eye development, or other problems resulting from damage to brain that affects nerves, muscles and bones, such as clubfoot or inflexible joints.

What these new numbers do not show

- These numbers are not real time estimates. They will reflect the outcomes of pregnancies reported with any laboratory evidence of possible Zika virus infection as of 12 noon every Thursday the week prior; numbers will be delayed one week.

- These numbers do not reflect outcomes among ongoing pregnancies.

- Although these outcomes occurred in pregnancies with laboratory evidence of Zika virus infection, we do not know whether they were caused by Zika virus infection or other factors.

Where do these numbers come from?

- These data reflect pregnancies reported to the US Zika Pregnancy Registry. CDC, in collaboration with state, local, tribal and territorial health departments, established this registry for comprehensive monitoring of pregnancy and infant outcomes following Zika virus infection.

- The data collected through this system will be used to update recommendations for clinical care, to plan for services and support for pregnant women and families affected by Zika virus, and to improve prevention of Zika virus infection during pregnancy.

These registries are covered by an assurance of confidentiality. This protection requires us to safeguard the information collected for the pregnant women and infants in the registries.

* Includes microcephaly, calcium deposits in the brain indicating possible brain damage, excess fluid in the brain cavities and surrounding the brain, absent or poorly formed brain structures, abnormal eye development, or other problems resulting from damage to the brain that affects nerves, muscles and bones, such as clubfoot or inflexible joints.

**Includes miscarriage, stillbirths, and terminations with evidence of the birth defects mentioned above

CDC: Eight Multistate Outbreaks of Human Salmonella Infections Linked to Live Poultry in Backyard Flocks

Wednesday, July 20th, 2016

“….In the eight outbreaks, 611 people infected with the outbreak strains of Salmonella were reported from 45 states…..”

A CDC Emergency Response Team (CERT) comes to Utah to investigate an unusual Zika case.

Tuesday, July 19th, 2016CDC is assisting in the investigation of a case of Zika in a Utah resident who is a family contact of the elderly Utah resident who died in late June. The deceased patient had traveled to an area with Zika and lab tests showed he had uniquely high amounts of virus—more than 100,000 times higher than seen in other samples of infected people—in his blood. Laboratories in Utah and at the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) reported evidence of Zika infection in both Utah residents.

State and local public health disease control specialists, along with CDC, are investigating how the second resident became infected. The investigation includes additional interviews with and laboratory testing of family members and health care workers who may have had contact with the person who died and trapping mosquitoes and assessing the risk of local spread by mosquitoes.

A CDC Emergency Response Team (CERT) is in Utah at the request of the Utah Department of Health. The team includes experts in infection control, virology, mosquito control, disease investigation, and health communications.

“The new case in Utah is a surprise, showing that we still have more to learn about Zika,” said Erin Staples, MD, PhD, CDC’s Medical Epidemiologist on the ground in Utah. “Fortunately, the patient recovered quickly, and from what we have seen with more than 1,300 travel-associated cases of Zika in the continental United States and Hawaii, non-sexual spread from one person to another does not appear to be common.”

As of July 13, 2016, 1,306 cases of Zika have been reported in the continental United States and Hawaii; none of these have been the result of local spread by mosquitoes. These cases include 14 believed to be the result of sexual transmission and one that was the result of a laboratory exposure.

Since early 2016, CDC has worked with state, local, and territorial public health officials to protect pregnant women from Zika infection, through these activities:

- Alerts to pregnant women to avoid travel to an area with active Zika transmission, to women in these areas to take steps to prevent mosquito bites, and to partners of pregnant women to use a condom to prevent sexual transmission during pregnancy.

- Development and distribution of PCR and IgM testing kits to confirm Zika virus infection.

- Establishment of CDC Emergency Response Teams to rapidly deploy to assist with Zika-related preparedness and response activities in the United States.

- Deployment of experts to assist in enhancement of mosquito surveillance and testing.

- Collaboration with FDA, blood collection centers, and other entities in the public and private sectors on enhancement of surveillance of blood donations.

- Guidance to prevent sexual transmission, particularly to women who are pregnant.

- Guidance for clinicians on the care of pregnant women who may have been exposed to Zika.

Studies in collaboration with Brazil, Colombia, and other countries to better understand the link between Zika infection and birth defects, including microcephaly.

For more information about Zika: http://www.cdc.gov/zika/.

Summary: CDC’s Detailed History of the 2014-2016 Ebola Response

Tuesday, July 19th, 2016Global Health Security: How is the U.S. doing?

Thursday, July 14th, 2016The Story Behind the Snapshot

At first glance, this photo taken on a set of concrete steps in Washington, D.C., may look like an ordinary group shot—but it took an extraordinary series of events to make it happen.

The photo shows colleagues from U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) and U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) standing alongside a team of 15 international experts from 13 different countries, known as the Joint External Evaluation Team. The team had been invited by the U.S. government to assess how well the country is prepared to prevent, detect, and respond to major public health threats. The goal was to receive an independent and unbiased evaluation of our capabilities.

We would never have arrived at this moment without these things: a wake-up call, a historic agreement, and a renewed commitment to work together to protect the world’s health.

Leading up to now: A brief timeline

Near the turn of this century, the emergence of diseases like severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS) and H5N1 influenza was a big wake-up call and showed the world more clearly than ever that a health threat anywhere is a threat everywhere — what affects one country affects us all.

Eleven years ago, countries came together to sign the International Health Regulations (IHR), a historic agreement which gave the world a new framework for stopping the spread of diseases across borders. The IHR obligates every country to prepare for, and report on, public health events that could have an international impact.

However, five years after the IHR went into effect, nearly 2/3 of countries were still unprepared to handle a public health emergency.

Two years ago, the Global Health Security Agenda (GHSA) gave countries common targets they can work toward to stop infectious disease in its tracks. This led to the need for the Joint External Evaluation Team, an independent group that travels to countries to report on how well public health systems are working to meet global health security goals.

Last October, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) and the Office of the Assistant Secretary for Preparedness and Response (ASPR) began working together to arrange for the team to visit the U.S.

In May, the team’s five-day visit took place. Two days were spent in Washington, D.C., assessing federal response capabilities. The remaining three days were spent at CDC, because the agency works in nearly all of the 19 technical areas included in the evaluation.

On the final day of their visit in Atlanta, the evaluation team shared their preliminary results.

What the team found

They recognized the high level of scientific expertise within CDC and other federal agencies, and the excellent reporting mechanisms managed by the federal government.

They also identified opportunities for improvement in some areas, such as:

- Combining and utilizing data from multiple surveillance systems, including systems that monitor human, animal, environmental, and plant health

- Conducting triage and long-term medical follow-up during major radiological disasters

- Communicating risks quickly and consistently with communities across the country

They specifically recognized the challenges any federal public health system faces, and advised the U.S. to continue improving the understanding of the IHR among different federal and state agencies. Their observations will help drive improvements for programs throughout CDC and the nation.

The U.S. requested this unbiased review of its response capabilities and hopes that the entire world will do the same. Like other countries who have undergone this process, the U.S. will soon share the final report of the Joint External Evaluation with the public.

For More Information

- Global Health Security Agenda: https://ghsagenda.org/

- Joint External Evaluation: https://ghsagenda.org/assessments.html

- CDC and the Global Health Security Agenda: http://www.cdc.gov/globalhealth/security/ghsagenda.htm

- Global Health Security: http://www.cdc.gov/globalhealth/healthprotection/ghs/index.html

- International Health Regulations: http://www.cdc.gov/globalhealth/healthprotection/ghs/ihr/index.html

CDC Releases Detailed History of the 2014-2016 Ebola Response in MMWR

Monday, July 11th, 2016The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) today will release a detailed account of the agency’s work on the largest, longest outbreak response in the agency’s history: the Ebola epidemic of 2014-2016. The series of articles, in a special supplement to CDC’s Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report (MMWR), comes on the second anniversary of the official activation of the agency’s emergency response to Ebola.

“The Ebola epidemic in West Africa killed thousands and directly or indirectly harmed millions of people living in the region,” said CDC Director Tom Frieden, M.D., M.P.H. “The resilience of those affected; the hard work by ministries of health and international partners; and the dedication, hard work, and expertise of mission-driven CDC employees helped avoid a global catastrophe. We must work to ensure that a preventable outbreak of this magnitude never happens again.”

The 2014-2016 Ebola epidemic was the first and largest epidemic of its kind, with widespread urban transmission and a massive death count of more than 11,300 people in Guinea, Liberia, and Sierra Leone. The epidemic took a devastating toll on the people of West Africa. Ending it took an extraordinary international effort in which the U.S. government played a major role.

CDC’s response was directed simultaneously at controlling the epidemic in West Africa and strengthening preparedness for Ebola in the United States. The new MMWR Ebola special supplement primarily focuses on the agency’s work during the first year and a half of the response. CDC activated its Emergency Operations Center (EOC) for the Ebola response on July 9, 2014. On August 5, 2014, CDC elevated the EOC to a Level 1 activation, its highest level. On March 31, 2016, CDC officially deactivated the EOC for the 2014-2016 Ebola response.

“The world came together in an unprecedented way—nations, organizations, and individuals—to respond to this horrible epidemic,” said Inger Damon, M.D., Ph.D., who served as incident manager for the CDC Ebola response during its first eight months. “CDC staff performed heroically and were an integral part of the U.S. all-government response, which involved many other agencies and branches of government.”

By the end of the CDC 2014-2016 Ebola response on March 31, 2016, more than 3,700 CDC staff, including all 158 Epidemic Intelligence Service Officers, had participated in international or domestic response efforts. There were 2,292 total deployments to Guinea, Liberia, and Sierra Leone and 3,544 total deployments overall (domestic and international) to support the response. Approximately 1,558 CDC responders have deployed to Guinea, Liberia, and Sierra Leone since the start of the response in July 2014 to the close of the response at the end of March 2016 – including 454 responders with repeat deployments. Even after the deactivation of the CDC 2014-2016 Ebola response, CDC continues its work to better understand and combat the Ebola virus and to assist Guinea, Liberia and Sierra Leone in the aftermath of the 2014-2016 Ebola epidemic; currently, CDC staff remain in CDC country offices in Guinea, Liberia, and Sierra Leone to help support the Global Health Security Agenda.

Experience responding to approximately 20 Ebola outbreaks since 1976 provided CDC and other international responders with an understanding of the disease and how to stop its spread. But unlike those shorter, self-limited outbreaks, the 2014-2016 Ebola epidemic in West Africa presented new and formidable challenges.

“This outbreak is a case study in why the Global Health Security Agenda is so important,” said Beth Bell, M.D., M.P.H., director of CDC’s National Center for Emerging and Zoonotic Infectious Diseases. “By the time the world understood there was an outbreak, it was already widespread – and had ignited the world’s first urban Ebola epidemic, with devastating results.”

This supplement tells the story of CDC’s contributions and shows the importance of partnerships among the international community. Some of the key CDC key activities detailed in this supplement include:

- In West Africa

- Establishing CDC teams in Guinea, Liberia, and Sierra Leone that transitioned into permanent CDC country offices in support of the Global Health Security Agenda and supporting the incident management systems in each of the affected countries

- Improving case detection and contact tracing; maintaining infection control in Ebola treatment units and general health care facilities; conducting detailed epidemiologic analyses of Ebola trends and transmission patterns

- Promoting the use of safe and dignified burial services to help stop spread of Ebola

- Fostering hope for a long-term solution for Ebola, including rollout of the STRIVE (Sierra Leone Trial to Introduce a Vaccine against Ebola) trial

- Strengthening surveillance and response capacities in surrounding, at-risk countries, and working with international partners to establish exit and entry risk assessment procedures at borders

- In the United States

- Reducing the likelihood of spread of Ebola through travel, including working with federal and state health officials to establish entry risk assessment procedures

- Establishing entry screening and monitoring of all travelers entering the U.S. from Ebola-affected areas

- Assisting state health departments in responding to domestic Ebola concerns

- Establishing trained and ready hospitals in the United States capable of safely caring for possible Ebola patients

- Forming CDC Rapid Ebola Preparedness (REP) response teams that could provide assistance within 24 hours to a health care facility managing a patient with Ebola.

- Identifying and distributing to state and local public health laboratories a laboratory assay that could reliably detect infection with the Ebola virus strain circulating in West Africa, and working with the Food and Drug Administration, the U.S. Department of Defense, and the Association of Public Health Laboratories to rapidly introduce and validate the assay in public health laboratories across the United States

- At CDC

- Modeling, in real time, predictions for the course of the epidemic that helped galvanize international support and generated estimates on various topics related to the response in West Africa and the risk for importation of cases into the United States

- Providing logistics support for the most ambitious CDC deployment in history

- Supporting laboratory needs at CDC’s Atlanta headquarters and transferring CDC laboratory expertise to the field

- Creating risk communication materials designed to help change behavior, decrease rates of transmission, and confront stigma, in West Africa and the United States

“This outbreak highlighted how much more we have to learn about Ebola, and it demonstrated that all countries are connected. An outbreak in one country is not just a national emergency, but a global one. This supplement’s detailed review of the 2014-2016 Ebola epidemic and CDC’s response, with many partners, shows the importance of preparedness. It is vital that countries are ready to quickly detect and respond to infectious disease outbreaks, and the international community is committed to increasing that readiness through the Global Health Security Agenda,” Dr. Frieden said. “Through our newly established country offices in Guinea, Liberia, and Sierra Leone, CDC will continue to help West Africa prevent an outbreak of this magnitude from happening again.”

The full MMWR Supplement on the response to the 2014-2016 Ebola virus disease epidemic and related information on the individual chapters available at http://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/ind2016_su.html.

###