Archive for the ‘Chikungunya’ Category

The World’s Deadliest Animal: Aedes Albopictus Mosquito

Monday, December 16th, 2019The meager, long-legged insect that annoys, bites, and leaves you with an itchy welt is not just a nuisance―it’s one of the world’s most deadly animals. Spreading diseases such as malaria, dengue, West Nile, yellow fever, Zika, chikungunya, and lymphatic filariasis, the mosquito kills more people than any other creature in the world.

In 2018, the number of severe cases of West Nile virus was nearly 25% higher in the Continental U.S. than the average incidence from 2008 to 2017.

In the past 30 years, the worldwide incidence of dengue has risen 30-fold. Forty percent of the world’s population, about 3 billion people, live in areas with a risk of dengue. Dengue is often a leading cause of illness in areas of risk.

Lymphatic filariasis (LF), a parasitic disease transmitted through repeated mosquito bites over a period of months, affects more than 120 million people in 72 countries

In 2017, 435,000 people died from malaria and millions become ill each year including about 2,000 returning travelers in the United States. Nearly half of the world’s population is at risk of this preventable disease.

You can protect yourself from these diseases by avoiding bites from infected mosquitoes.

CDC is committed to providing scientific leadership in fighting these diseases, at home and around the world. From its origins, CDC played a critical role in eliminating malaria from the U.S.

CDC Entomologist, Seth Irish, examines a discarded water bottle for the presence of mosquito larvae, during a training exercise in Dhaka, Bangladesh

Since 2001, global health action has cut the number of malaria deaths in half―saving almost 7 million lives. CDC co-implements the President’s Malaria Initiative in 24 countries and leads Malaria Zero efforts to eliminate malaria from Haiti and efforts to eliminate lymphatic filariasis from Haiti and America Samoa. Haiti is an example of how Mass Drug Administration can reduce spread of LF.

Today, CDC works to eliminate the global burden of malaria and other mosquito-borne diseases. From conducting research to developing tools and approaches to better prevent, detect, and control mosquito-borne diseases, to mitigating drug and insecticide resistance, to accelerating progress towards disease elimination, CDC scientists are working around the world to protect people from mosquito-borne diseases.

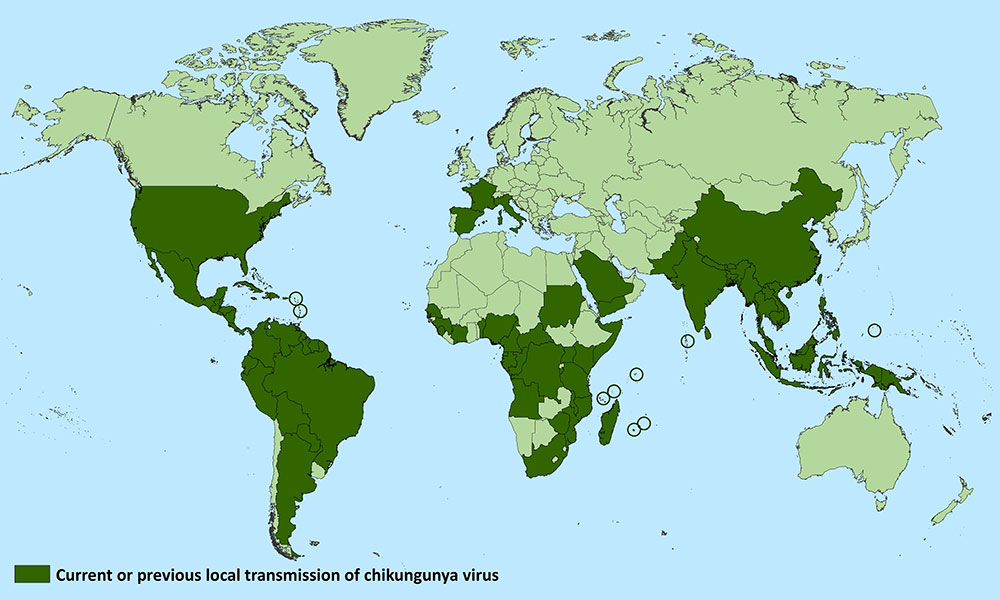

New research shows that the geographical range of vector-borne diseases such as chikungunya, dengue fever, leishmaniasis, and tick-borne encephalitis (TBE) is expanding rapidly.

Tuesday, April 16th, 2019“……..Global warming has allowed mosquitoes, ticks and other disease-carrying insects to proliferate, adapt to different seasons, and invade new territories across Europe over the past decade–with accompanying outbreaks of dengue in France and Croatia, malaria in Greece, West Nile Fever in Southeast Europe, and chikungunya virus in Italy and France. …….”

Results from a phase 2 trial of a live-attenuated, measles-vectored chikungunya vaccine (MV-CHIK) showed the vaccine to be safe, well-tolerated, and immunogenic.

Sunday, November 11th, 2018Immunogenicity, safety, and tolerability of the measles-vectored chikungunya virus vaccine MV-CHIK: a double-blind, randomised, placebo-controlled and active-controlled phase 2 trial

DOI:https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(18)32488-7

CDC

Symptoms

- Most people infected with chikungunya virus will develop some symptoms.

- Symptoms usually begin 3–7 days after being bitten by an infected mosquito.

- The most common symptoms are fever and joint pain.

- Other symptoms may include headache, muscle pain, joint swelling, or rash.

- Chikungunya disease does not often result in death, but the symptoms can be severe and disabling.

- Most patients feel better within a week. In some people, the joint pain may persist for months.

- People at risk for more severe disease include newborns infected around the time of birth, older adults (≥65 years), and people with medical conditions such as high blood pressure, diabetes, or heart disease.

- Once a person has been infected, he or she is likely to be protected from future infections.

Diagnosis

- The symptoms of chikungunya are similar to those of dengue and Zika, diseases spread by the same mosquitoes that transmit chikungunya.

- See your healthcare provider if you develop the symptoms described above and have visited an area where chikungunya is found.

- If you have recently traveled, tell your healthcare provider when and where you traveled.

- Your healthcare provider may order blood tests to look for chikungunya or other similar viruses like dengue and Zika.

Treatment

- There is no vaccine to prevent or medicine to treat chikungunya virus.

- Treat the symptoms:

- Get plenty of rest.

- Drink fluids to prevent dehydration.

- Take medicine such as acetaminophen (Tylenol®) or paracetamol to reduce fever and pain.

- Do not take aspirin and other non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDS until dengue can be ruled out to reduce the risk of bleeding).

- If you are taking medicine for another medical condition, talk to your healthcare provider before taking additional medication.

- If you have chikungunya, prevent mosquito bites for the first week of your illness.

- During the first week of infection, chikungunya virus can be found in the blood and passed from an infected person to a mosquito through mosquito bites.

- An infected mosquito can then spread the virus to other people.

More detailed information can be found on CDC’s chikungunya web page for healthcare providers

India, 2016: Severe Manifestations of Chikungunya Fever in Kids

Saturday, August 18th, 2018“……A total of 49 children had chikungunya fever; 36 had nonsevere disease and 13 had severe disease. All patients with severe disease were admitted to the PICU; 11 had illness consistent with the case definition of severe sepsis and septic shock, and 2 had acute liver failure. Of the 36 patients with nonsevere disease, 16 were admitted to the PICU (11 had seizures, 4 had fluid-responsive shock, 1 had peripheral cyanosis and mottling) and 20 were admitted to the pediatric high-dependency unit (3 had bleeding manifestations, 4 had severe abdominal pain, 2 had underlying cyanotic congenital heart disease, 2 had body temperature >40.3°C with irrelevant talking, 7 had dehydration, and 2 had severe rash). The median age was 12 years for patients with severe disease and 6.5 years for patients with nonsevere disease; male sex predominated in both groups (Table). Frequency of fever, body ache, arthralgia, and vomiting were similar for both groups. Peripheral cyanosis, along with mottling of skin and encephalopathy, was significantly higher in the group with severe disease. Serum albumin was significantly lower in the group with severe disease (3 vs. 3.75 g/dL). Of the 11 children with septic shock, 8 were admitted to the hospital within 24 hours of developing fever; 9 had hypotensive shock, and 2 had compensated shock. In this group, 6 children required 1 vasoactive agent, 3 children required 2 vasoactive agents, and 2 children required 3 vasoactive agents. Dopamine was used in 8 patients, dobutamine in 5 patients, epinephrine in 2 patients, and norepinephrine in 2 patients. The median duration of vasoactive support was 56 hours (range 31–114 hours), and the median vasoactive inotropic score in the first 24 hours was 10 (range 5–90; score >15–20 is considered serious). A vasoactive inotropic score >20 was seen in 2 children. Mean pH was 7.26 (reference range 7.35–7.45), mean lactate 5.1 mmol/L (reference range <2 mmol/L), mixed venous saturation 55% (reference range 70%–80%), and mean base excess at admission –7.7 mEq (reference range –2 to 2 mEq). Of the 2 children with acute liver failure with encephalopathy, 1 had dengue virus (positive dengue IgM by enzyme immunoassay) and the other had hepatitis E virus (reactive anti–hepatitis E IgM by enzyme immunoassay) co-infection…..”

| Sharma PK, Kumar M, Aggarwal GK, Kumar V, Srivastava R, Sahani A, et al. Severe Manifestations of Chikungunya Fever in Children, India, 2016. Emerg Infect Dis. 2018;24(9):1737-1739. https://dx.doi.org/10.3201/eid2409.180330

|

Sterile Insect Technique on Aedes aegypti mosquitoes

Monday, July 16th, 2018In an international partnership between CSIRO, Verily and James Cook University, scientists used specialised technology to release millions of sterilised male Aedes aegypti mosquitoes across the Cassowary Coast in Queensland in a bid to combat the global pest.

CSIRO Director of Health and Biosecurity Dr Rob Grenfell said the results were a major win in the fight against diseases-spreading mosquitoes.

“The invasive Aedes aegypti mosquito is one of the world’s most dangerous pests, capable of spreading devastating diseases like dengue, Zika and chikungunya and responsible for infecting millions of people with disease around the world each year,” Dr Grenfell said.

“Increased urbanisation and warming temperatures mean that more people are at risk, as these mosquitoes which were once relegated to areas near the equator forge past previous climatic boundaries.

“Although the majority of mosquitoes don’t spread diseases, the three mostly deadly types the Aedes, Anopheles and Culex are found almost all over the world and are responsible for around 17 per cent of infectious disease transmissions globally.”

From November 2017 to June this year, non-biting male Aedes aegypti mosquitoes sterilised with the natural bacteria Wolbachia were released in trial zones along the Cassowary Coast in North Queensland.

They mated with local female mosquitoes, resulting in eggs that did not hatch and a significant reduction of their population.

“Our heartfelt thanks goes out to the Innisfail community who literally opened their doors to our team, letting us install mosquito traps around their homes and businesses – we couldn’t have done this without your support,” Dr Grenfell said.

The process, known as the Sterile Insect Technique, has been successfully used since the 1950s but the challenge in making it work for mosquitoes like the Aedes aegypti has been rearing enough mosquitoes, removing biting females, identifying the males and then releasing the huge numbers needed to suppress a population.

To address this challenge, Verily, an affiliate of Alphabet Inc, developed a mosquito rearing and sex sorting and release technology as part of its global Debug project.

“We’re very pleased to see strong suppression of these dangerous biting female Aedes aegypti mosquitoes,” Verily’s Nigel Snoad said.

“We are particularly thankful to the people of Innisfail for their strong support, which has been incredible.

“We came to Innisfail with CSIRO and JCU to see how this approach worked in a tropical environment where these mosquitoes thrive, and to learn what it was like to operate our technology with research collaborators as we work together to find new ways to tackle these dangerous mosquitoes.”

Scientists compared the number of Aedes aegypti mosquitoes trapped in release sites and control zones to monitor and track populations.

The millions of mosquitoes needed for the trial were reared at James Cook University in Cairns.

To produce the three million male mosquitoes needed for the trial, researchers at James Cook University (JCU) in Cairns set out to raise almost 20 million Aedes aegypti.

“We allowed for the possibility of deaths during the process, as well as the need to sift out the female half of the population,” Dr Kyran Staunton from James Cook University said.

“Verily’s technology enabled us to do the sex sorting faster and with much higher accuracy.

“We learnt a lot from collaborating on this first tropical trial and we’re excited to see how this approach might be applied in other regions where Aedes aegypti poses a threat to life and health.”

“The health of our nation is paramount as we help Australia achieve its vision to become one of the healthiest nations on earth,” CSIRO Chief Executive Dr Larry Marshall said.

“By enabling industry partners like Verily to leverage the world-leading health capability we have built in CSIRO we can deliver this moonshot and tackle some of the world’s most wicked challenges with science.”

Scientists have identified a molecule found on human cells and some animal cells that could be a useful target for drugs against chikungunya virus infection

Sunday, May 27th, 2018“Scientists have identified a molecule found on human cells and some animal cells that could be a useful target for drugs against chikungunya virus infection and related diseases, according to new research published in the journal Nature. A team led by scientists at Washington University School of Medicine in St. Louis conducted the research, which was funded in part by the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (NIAID), part of the National Institutes of Health.

Chikungunya, an alphavirus, is transmitted to humans by the bite of an infected mosquito. Currently no specific treatment is available for chikungunya virus infection, which can cause fever and debilitating joint pain and arthritis. Small, sporadic outbreaks of chikungunya occurred in Africa, Asia, Europe, and the Indian and Pacific Oceans after the virus was identified in the 1950s. In 2013, the virus spread to the Americas and has since caused a widespread and ongoing epidemic.

In this study, scientists aimed to better understand which traits make humans susceptible to chikungunya virus infection. Using the gene-editing tool CRISPR-Cas9, they performed a genome-wide screen that identified the molecule Mxra8 as a key to the entry of chikungunya virus and related viruses into host cells. In the laboratory, scientists were able to reduce the ability of chikungunya virus to infect cells by editing the human and mouse genes that encode Mxra8. The researchers also administered anti-Mxra8 antibodies to mice and infected the mice with chikungunya virus or O’nyong-nyong virus, another alphavirus. The antibody-treated mice had significantly lower levels of virus infection and related foot swelling as compared with a control group.

These findings, along with future studies to better understand how chikungunya virus interacts with Mxra8, could help inform development of drugs to treat diseases caused by alphaviruses, according to the authors.

Article

R Zhang et al. Mxra8 is a receptor for multiple arthritogenic alphaviruses. Nature DOI: 10.1038/s41586-018-0121-3 (2018).

Who

NIAID Director Anthony S. Fauci, M.D., is available for comment. Patricia M. Repik, Ph.D., program officer for Emerging Viral Diseases in the Virology Branch of NIAID’s Division of Microbiology and Infectious Diseases, is also available for comment.

Contact

To schedule interviews, please contact Jennifer Routh, (301) 402-1663, NIAIDNews@niaid.nih.gov (link sends e-mail).

This press release describes a basic research finding. Basic research increases our understanding of human behavior and biology, which is foundational to advancing new and better ways to prevent, diagnose, and treat disease. Science is an unpredictable and incremental process — each research advance builds on past discoveries, often in unexpected ways. Most clinical advances would not be possible without the knowledge of fundamental basic research.

NIAID conducts and supports research — at NIH, throughout the United States, and worldwide — to study the causes of infectious and immune-mediated diseases, and to develop better means of preventing, diagnosing and treating these illnesses. News releases, fact sheets and other NIAID-related materials are available on the NIAID website.

About the National Institutes of Health (NIH): NIH, the nation’s medical research agency, includes 27 Institutes and Centers and is a component of the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. NIH is the primary federal agency conducting and supporting basic, clinical, and translational medical research, and is investigating the causes, treatments, and cures for both common and rare diseases. For more information about NIH and its programs, visit www.nih.gov.

NIH…Turning Discovery Into Health®”

U.S. trends in occurrence of nationally reportable vectorborne diseases during 2004–2016.

Wednesday, May 2nd, 2018Rosenberg R, Lindsey NP, Fischer M, et al. Vital Signs: Trends in Reported Vectorborne Disease Cases — United States and Territories, 2004–2016. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. ePub: 1 May 2018. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.15585/mmwr.mm6717e1.

Key Points

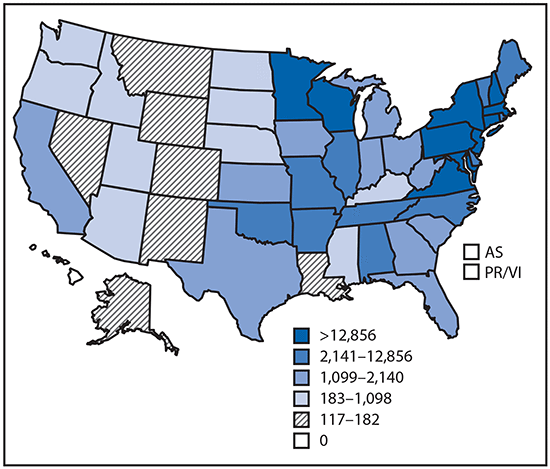

•A total of 642,602 cases of 16 diseases caused by bacteria, viruses, or parasites transmitted through the bites of mosquitoes, ticks, or fleas were reported to CDC during 2004–2016. Indications are that cases were substantially underreported.

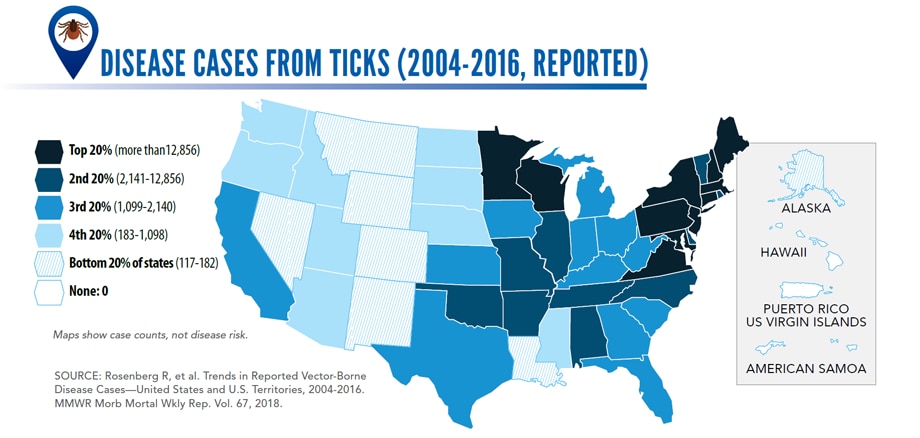

•Tickborne diseases more than doubled in 13 years and were 77% of all vectorborne disease reports. Lyme disease accounted for 82% of all tickborne cases, but spotted fever rickettsioses, babesiosis, and anaplasmosis/ehrlichiosis cases also increased.

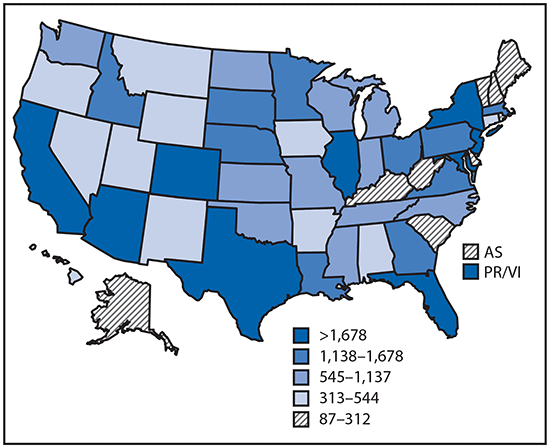

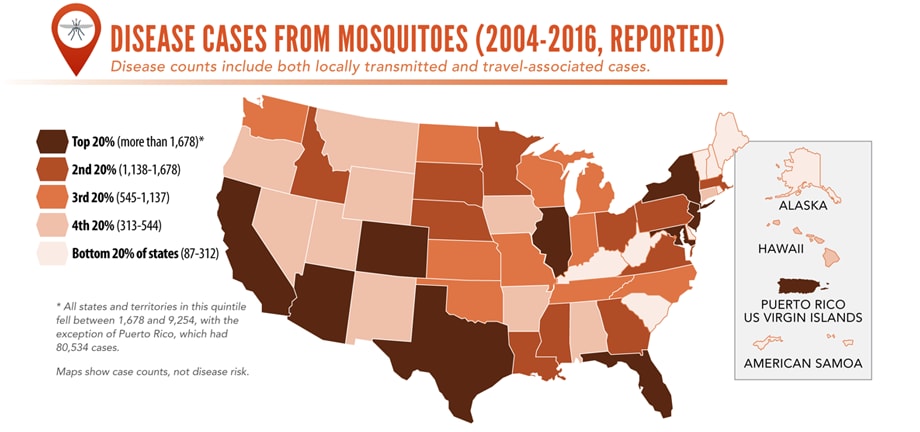

•Tickborne disease cases predominated in the eastern continental United States and areas along the Pacific coast. Mosquitoborne dengue, chikungunya, and Zika viruses were almost exclusively transmitted in Puerto Rico, American Samoa, and the U.S. Virgin Islands, where they were periodically epidemic. West Nile virus, also occasionally epidemic, was widely distributed in the continental United States, where it is the major mosquitoborne disease.

•During 2004–2016, nine vectorborne human diseases were reported for the first time from the United States and U.S. territories. The discovery or introduction of novel vectorborne agents will be a continuing threat.

•Vectorborne diseases have been difficult to prevent and control. A Food and Drug Administration–-approved vaccine is available only for yellow fever virus. Many of the vectorborne diseases, including Lyme disease and West Nile virus, have animal reservoirs. Insecticide resistance is widespread and increasing.

•Preventing and responding to vectorborne disease outbreaks are high priorities for CDC and will require additional capacity at state and local levels for tracking, diagnosing, and reporting cases; controlling vectors; and preventing transmission.

Reported cases* of tickborne disease — U.S. states and territories, 2004–2016

Reported cases* of mosquitoborne disease — U.S. states and territories, 2004–2016

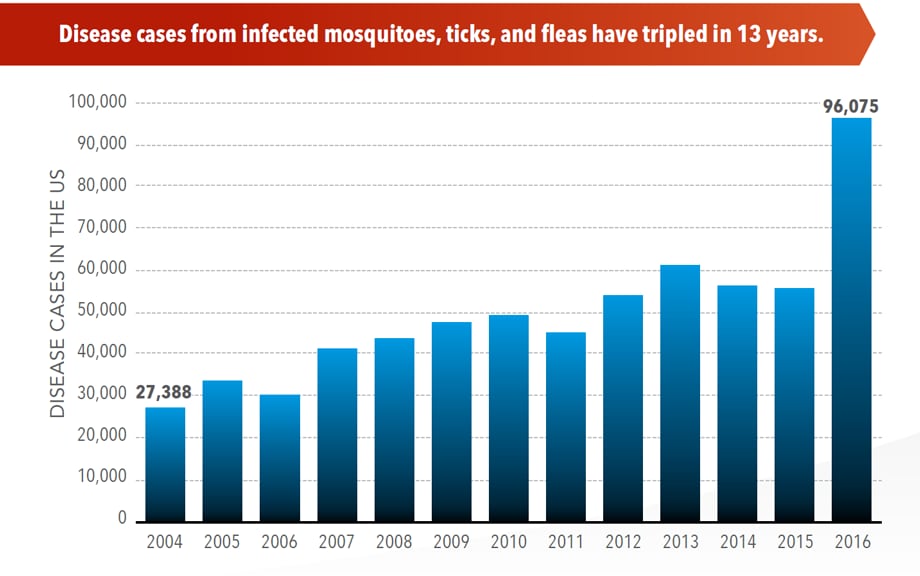

Reported nationally notifiable mosquitoborne,* tickborne, and fleaborne† disease cases — U.S. states and territories, 2004–2016

The number of reported cases of disease from mosquito, tick, and flea bites has more than tripled in the USA (2004-2016)

Wednesday, May 2nd, 2018More cases in the US (2004-2016)

- The number of reported cases of disease from mosquito, tick, and flea bites has more than tripled.

- More than 640,000 cases of these diseases were reported from 2004 to 2016.

- Disease cases from ticks have doubled.

- Mosquito-borne disease epidemics happen more frequently.

More germs (2004-2016)

- Chikungunya and Zika viruses caused outbreaks in the US for the first time.

- Seven new tickborne germs can infect people in the US.

More people at risk

- Commerce moves mosquitoes, ticks, and fleas around the world.

- Infected travelers can introduce and spread germs across the world.

- Mosquitoes and ticks move germs into new areas of the US, causing more people to be at risk.

The US is not fully prepared

- Local and state health departments and vector control organizations face increasing demands to respond to these threats.

- More than 80% of vector control organizations report needing improvement in 1 or more of 5 core competencies, such as testing for pesticide resistance.

- More proven and publicly accepted mosquito and tick control methods are needed to prevent and control these diseases.

Vector-Borne Diseases Reported by States to CDC

Mosquito-borne diseases

- California serogroup viruses

- Chikungunya virus

- Dengue viruses

- Eastern equine encephalitis virus

- Malaria plasmodium

- St. Louis encephalitis virus

- West Nile virus

- Yellow fever virus

- Zika virus

Tickborne diseases

- Anaplasmosis/ehrlichiosis

- Babesiosis

- Lyme disease

- Powassan virus

- Spotted fever rickettsiosis

- Tularemia

Fleaborne disease

- Plague

For more information: https://wwwn.cdc.gov/nndss/

Chikungunya – Mombasa, Kenya

Wednesday, February 28th, 2018From mid-December 2017 through 3 February 2018, the Ministry of Health (MoH) of Kenya reported 453 cases, including 32 laboratory-confirmed cases and 421 suspected cases, of chikungunya from Mombasa County.

The outbreak was detected due to an increase in the number of patients presenting to health facilities in Mombasa Country with high grade fever, joint pain and general body weakness.

On 13 December 2017, eight blood samples from two private hospitals were collected and submitted to the Kenya Medical Research Institute (KEMRI) arbovirus laboratory in Nairobi. Of the eight samples tested, four were positive for chikungunya and four were positive for dengue by polymerase chain reaction (PCR) analysis. On 4 January 2018, blood samples were collected from 32 additional suspected cases and sent to the KEMRI laboratory. Of these, 27 samples tested positive and five samples tested negative for chikungunya by PCR.

A large proportion, approximately 70%, of cases reported severe joint pain and high grade fever. The scale of this outbreak has likely been underestimated given the under-reporting of cases and low levels of health-seeking behaviors among the affected population. The large mosquito breeding sites in affected areas and inadequate vector control mechanisms also represent major propagating factors.

Based on reports from peripheral health facilities, the outbreak has spread to the six sub-counties (Changamwe, Jomvu, Kisauni, Likoni, Mvita and Nyali) of Mombasa and one in Kilifi: with the majority of suspected cases reported from Mvita and Likoni in Mombasa.

Public health response

The following public health measures are ongoing:

- WHO is supporting the MoH in drafting a chikungunya response plan for Mombasa County;

- WHO is supporting the National Emergency Operations Centre with analyzing data and developing situation reports;

- Vector control activities, including eliminating mosquito breeding sites, fogging and indoor residual spraying;

- Chikungunya outbreak alert and fact sheet were issued to all health facilities, including private hospitals, in the affected areas;

- Information, education and communication materials were developed and distributed to households by the community health volunteers.

WHO risk assessment

Based on the available information, the risk of continued transmission in affected areas and spread to unaffected areas cannot be ruled out.

Mombasa is the second largest city in Kenya with approximately 1.2 million inhabitants. The city has a rapidly growing population, and some areas experience overcrowding, numerous open dump sites, inadequate drainage, stagnant water and ample breeding sites for mosquitoes. These factors make Mombasa particularly vulnerable to vector-borne diseases. Mombasa County is also a popular tourist destination and a sub-regional transportation hub with connections to Rwanda, Tanzania and Ethiopia. This is the first time that active circulation of chikungunya has been laboratory confirmed in Mombasa. Further sequencing of the circulating virus is therefore needed to better assess the current epidemiologic situation.

WHO advice

Personal protection

Basic precautions should be taken by people living in and travelling to Mombasa County. These precautions include the use of repellents, wearing long sleeves and pants and ensuring rooms are fitted with screens to prevent mosquitoes from entering.

Clothing which minimizes skin exposure to the day-biting mosquitoes is advised. Repellents can be applied to exposed skin or to clothing in strict accordance with product label instructions. Repellents should contain DEET (N, N-diethyl-3-methylbenzamide), IR3535 (3-[N-acetyl-N-butyl]-aminopropionic acid ethyl ester) or icaridin (1-piperidinecarboxylic acid, 2-(2-hydroxyethyl)-1-methylpropylester). The use of air conditioning, window screens, mosquito coils or other insecticide vaporizers as well as sleeping under a mosquito bed net even during the day are recommended to prevent biting by mosquitos indoors.

Vector control

Prevention and control relies heavily on reducing the number of the natural and artificial water-filled container habitats that act as mosquito breeding sites. This requires mobilizing the affected communities, strengthening entomological monitoring to assess impact of control measures and implementing additional controls as needed to avoid misconceptions and false rumors.

WHO advises against the application of any travel or trade restrictions on Kenya based on the information currently available.

For more information, please see the link below:

Italy’s chikungunya outbreak has expanded to a second region, and the total number of suspected or confirmed cases has climbed to 298

Wednesday, October 11th, 2017“…..Italy is currently experiencing four clusters of autochthonous chikungunya cases in the cities of Anzio, Latina and Rome in the Lazio region, and the city of Guardavalle Marina in the Calabria region. Autochthonous transmission of mosquito-borne infections is not unexpected in areas where Aedes albopictus mosquitoes are established and at a time when environmental conditions are favouring mosquito abundance and activity.

This is the second time that Italy is facing an outbreak of autochthonous chikungunya, following an outbreak in the Emilia-Romagna region in 2007. Within the European Union, apart from Italy, only France reported outbreaks of autochthonous cases in the past, i.e. in 2010, 2014 and 2017. Autochthonous chikungunya transmission is estimated to have started in Anzio in early-/mid-June 2017 or earlier. Subsequently, autochthonous transmission was detected in Rome and Latina, and more recently in Guardavalle Marina.

The likelihood of further spread within Italy is still moderate, with suitable but less favourable conditions for vector activity in the coming weeks. In the areas already affected, it is likely that more cases will be identified in the near future. ….”