Archive for the ‘Cholera’ Category

Cholera in Zimbabwe: As of 3 October 2018, 8535 cumulative cases, including 163 laboratory-confirmed cases, and 50 deaths have been reported (case fatality rate: 0.6%).

Tuesday, October 9th, 2018Cholera – Zimbabwe

Since the last Disease Outbreak News was published on 20 September (with data as of 15 September), an additional 4914 cases have been reported including 92 laboratory-confirmed cases.

The cholera outbreak in Harare was declared by the Ministry of Health and Child Care (MoHCC) of Zimbabwe on 6 September 2018 and notified to WHO on the same day. As of 3 October 2018, 8535 cumulative cases, including 163 laboratory-confirmed cases, and 50 deaths have been reported (case fatality rate: 0.6%). Of these 8535 cases, 98% (8341 cases) were reported from the densely populated capital Harare (Figure 1). The most affected suburbs in Harare are Glen View and Budiriro.

Of the 8340 cases for which age is known, the majority (56%) are aged between 5 and 35 years old. Males and females have been equally affected by the outbreak. From 4 September through 3 October, the majority of deaths were reported from health care institutions.

The pathogen is known to be Vibrio cholera O1 serotype Ogawa. Since confirmation on 6 September 2018, a multi-drug resistant strain has been identified and is in circulation; however, this does not affect the treatment of most cases, where supportive care such as rehydration solutions are used. Antibiotics are only recommended for severe cases. Furthermore, the antibiotic which is being used for severe cases in Harare is Azithromycin which remains effective in the majority of cases.

Contaminated water sources, including wells and boreholes are suspected as the source of the outbreak.

Figure 1: Cholera cases in Harare, Zimbabwe from 4 September through 3 October 2018

igure 2: Cholera cases in Zimbabwe from 4 September through 1 October 2018

Public health response

-

- On 3 October 2018, an oral cholera vaccine mass vaccination campaign started in Harare City and surrounding areas such as Chitungwiza and Epworth. WHO is supporting the MoHCC on a strategy for rolling out the vaccination campaign, as well as implementing the campaign and sensitizing the public about the vaccine. More than 600 health workers have been trained to carry out the campaign. On 27 September 2018, 500 000 doses have arrived in Harare. In total, 2.7 million doses have been approved for two rounds of vaccination.

- WHO and experts from the Global Outbreak Alert and Response Network (GOARN) are providing technical oversight into case management and providing guidance on the interpretation of laboratory findings to guide the choice of antibiotics.

- Four cholera treatment centres (CTCs) have been established. UNICEF has prepositioned seven tents at Glenview for the CTC and Oxfam is providing mobile toilets in three CTCs.

- The key risk communication and community engagement interventions have been on raising awareness on cholera prevention through the mass media and social media, and working with specific community groups, including Apostolic sect leaders and Apostolic women’s groups.

- Sixty volunteers have been deployed to provide risk communication, community engagement and social mobilization support to CTCs in Budiriro and Glen View. Health and hygiene promotion is taking place through drama shows at schools and business centres, roadshows and door-to-door visits, which also focuses on identification and case referral.

- Water, sanitation and hygiene (WASH) activities include enforcement of regulations for food vendors, City of Harare fixing burst water pipes and increasing the water supply to hotspots, with private sector players supporting installation of water tanks and water trucking.

- UNICEF is supporting distribution of non-food items (soap, buckets), along with Oxfam, Christian Care, Mercy Corps and Welthungerhilfe (WHH), as well as key components of community mobilization.

- WHO has sent supplies to treat 3800 people and arrangements are in place for additional supplies to arrive in the coming days. In addition, more than 44 000 litres of ringers lactate from South Africa have arrived in country and the RDTs are being cleared from the airport.

- Since the cholera outbreak was declared on 6 September 2018, weekly meetings of the Inter-Agency Coordination Committee on Health (IACCH) have been held.

- On 12 September 2018, following the declaration of the cholera outbreak as a state of disaster, the Cabinet Committee on Emergency Preparedness and Disaster Management was reactivated.

- On 18 September 2018, the national government set up an inter-ministerial committee on the cholera outbreak, involving all major government stakeholders, to provide leadership and to monitor the cholera response efforts and provide regular briefs to the President.

- On 21 September 2018, the National Emergency Operations Centre (EOC) was activated, with support provided by local business organizations. The Incident Command Structure (ICS) was finalized and will be published by the EOC.

- On 1 October 2018, Econet began fixing Information and Communications Technology equipment in the EOC in MoHCC of Zimbabwe to support real time reporting.

- On 29 September 2018, a rapid assessment of surveillance was conducted in coordination with the United States Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (US CDC).

WHO risk assessment

The outbreak started on 5 September and the number of cases notified per day continues to rapidly increase, particularly in Glen View and Budiriro suburbs of Harare. Cases with epidemiological links to this outbreak have been reported from other provinces across the country. Glen View, which is the epicentre of the outbreak, is an active informal trading area where people come from across the city and the rest of the country to trade. Key risk factors for cholera in Zimbabwe include the deterioration of sanitary and health infrastructure and increasing rural-urban migration which further strains the water and sanitation infrastructure. Since the beginning of the outbreak, 135 cases have been reported from provinces outside Harare. With the upcoming rainy season in November, there is a concern that cases may increase in the hotspots. In Harare, contaminated water from boreholes and wells is suspected to be the source of the outbreak. Sixty-nine percent of the population in Harare relies on these boreholes and wells as a source of water. The water supply situation in Harare remains dire due to the high demand of water that is not being met by the city supply though this is a focus of response efforts. The country’s available response capacities are overstretched as authorities are already responding to a large typhoid outbreak which started in August 2018. WHO assessed the overall public health risk to be high at the national level and moderate at the regional and low at global levels.

WHO advice

WHO recommends proper and timely case management in CTCs. Increasing access to potable water, improving sanitation infrastructure, and strengthening hygiene and food safety practices in affected communities are the most effective means to prevent and control cholera. Key public health communication messages should be provided to the affected population.

WHO advises against any restrictions on travel or trade to or from Zimbabwe based on the information currently available in relation to this outbreak.

For further information, please refer to:

What’s in a Cholera Kit?

Monday, October 8th, 2018

Overview: In 2016 WHO introduced the Cholera Kits. These kits replace the Interagency Diarrhoeal Disease Kit (IDDK) which had been used for many years. The Cholera Kit is designed to be flexible and adaptable for preparedness and outbreak response in different contexts. The overall Cholera Kit is made up of an Investigation Kit, Laboratory materials, 3 Treatment Kits (community, periphery and central) and a Hardware Kit. The Treatment and Hardware Kits are each composed of individual modules. Each of the kits and modules can be ordered independently based on field need. To support orders, a Cholera Kit Calculation Tool was developed. This course is made up of two parts: a short introduction to the Cholera Kits and modules, and a demonstration of the Cholera Kit Calculation Tool.

WHO and partners is launching today an oral cholera vaccination (OCV) campaign to protect 1.4 million people at high risk of cholera in Harare.

Thursday, October 4th, 2018The Government of Zimbabwe with the support of the World Health Organization (WHO) and partners is launching today an oral cholera vaccination (OCV) campaign to protect 1.4 million people at high risk of cholera in Harare.

The immunization drive is part of efforts to control a cholera outbreak, which was declared by the health authorities on 6 September 2018.The vaccines were sourced from the global stockpile, which is funded by Gavi, the Vaccine Alliance. Gavi is also funding operational costs for the campaign.

The government, with the support of WHO and partners, has moved quickly to implement key control efforts, including enhanced surveillance, the provision of clean water and hygiene promotion, cleaning of blocked drains and setting up dedicated treatment centres. The cholera vaccination campaign will complement these ongoing efforts.

“The current cholera outbreak is geographically concentrated in the densely populated suburbs of Harare,” said Dr Matshidiso Moeti, WHO’s Regional Director for Africa. “We have a window of opportunity to strike back with the oral cholera vaccine now, which along with other efforts will help keep the current outbreak in check and may prevent it from spreading further into the country and becoming more difficult to control.”

The campaign will be rolled out in two rounds, focusing on the most heavily affected suburbs in Harare and Chitungwiza, which is 30 km southeast of the capital city. To ensure longer-term immunity to the population, a second dose of the vaccine will be provided in all areas during a second round to be implemented at a later stage.

“Cholera is a disease that can be prevented with clean water and sanitation: there is no reason why people should still be dying from this horrific disease,” said Dr Seth Berkley, CEO of Gavi, the Vaccine Alliance. “Gavi has worked hard to ensure the global cholera vaccine stockpile remains fully stocked and ready to help stop outbreaks such as this. The government of Zimbabwe have done a great job in fighting this outbreak; we must now hope that these lifesaving vaccines can help to prevent any more needless deaths.”

WHO is supporting the Ministry of Health and Child Care on a strategy for rolling out the vaccination campaign, as well as implementing the campaign and sensitizing the public about the vaccine. More than 600 health workers have been trained to carry out the campaign.

The vaccination drive will take place at fixed and mobile sites including health facilities, schools and shopping centres.

WHO experts in collaboration with partners are supporting the national authorities to intensify surveillance activities, improve diagnostics, and strengthen infection and prevention control in communities and health facilities. They have also provided cholera supplies of oral rehydration salts, intravenous fluids and antibiotics sufficient to treat 6000 people.

The health sector alone cannot prevent and control cholera outbreaks. This requires strong partnerships and a response across multiple sectors, especially in the investment and maintenance of community-wide water, sanitation and hygiene facilities.

Zimbabwe has experienced frequent outbreaks of cholera, with the largest outbreak occurring from August 2008 to May 2009 and claiming more than 4000 lives.

Yemen’s cholera outbreak – the worst in the world – is accelerating again, with roughly 10,000 suspected cases per week

Wednesday, October 3rd, 2018- “….for the first eight months of the year, 154,527 suspected cases of cholera…. were recorded across the country, with 196 deaths…..”

Cholera in Zimbabwe: Current status

Saturday, September 22nd, 2018On 6 September 2018, a cholera outbreak in Harare was declared by the Ministry of Health and Child Care (MoHCC) of Zimbabwe and notified to WHO on the same day. Twenty-five patients were admitted to a hospital in Harare presenting with diarrhoea and vomiting on 5 September. The first case, a 25-year-old woman, presented to a hospital and died on 5 September. A sample from the woman tested positive for Vibrio cholerae serotype O1 Ogawa. All 25 patients had typical cholera symptoms including excessive vomiting and diarrhoea with rice watery stools and dehydration. The MoHCC declared the outbreak after 11 cases were confirmed for cholera using rapid diagnostic test (RDT) kits and the clinical presentation. Thirty-nine stool samples were collected for culture and sensitivity, 17 of which tested positive for V. cholerae serotype O1 Ogawa.

There has been rapid increase in the number of suspected cases reported per day since 1 September; there was a peak with 473 suspected cases notified on 9 September. As of 15 September 2018, 3621 cumulative suspected cases, including 71 confirmed cases, and 32 deaths have been reported (case fatality ratio: 0.8 %); of these, 98% (3564 cases) were reported from the densely populated capital Harare. The most affected suburbs in Harare are Glen View and Budiriro.

Cases with epidemiological links to cases from Harare have been recently reported from across the country, including in Mashonaland Central Province (Shamva District), Midlands Province (Gokwe North District), Manicaland Province (Buhera and Makoni districts), Masvingo Province and Chitungwiza City.

Public health response

-

- The MoHCC declared the cholera outbreak in Harare City on 6 September; the Government declared the outbreak an emergency and subsequently a disaster on 13 and 14 September, respectively.

- Outbreak coordination committees at the national and district levels have been established.

- WHO and the WHO Country Office (WCO) are supporting the MoHCC with coordination, scaling up the response, strengthening surveillance and mobilizing both national and international health experts to form a cholera surge team.

- WHO experts are providing technical support to laboratories, improving diagnostics and strengthening infection and prevention control (IPC) in communities and health clinics.

- The Government is assessing the potential benefits of conducting an oral cholera vaccine (OCV) campaign; WHO is deploying an expert in OCV campaigns to Harare to support this assessment.

- A cholera treatment centre (CTC) was established by Médecins Sans Frontières (MSF) in Glen View, Harare; MSF has provided extra nurses to support the response.

- The recruitment of additional nurses to strengthen the response is ongoing.

- WHO is providing supplies which contain oral rehydration solution, intravenous fluids and antibiotics for the treatment of patients in CTCs set up by partners.

- Risk communication activities in affected and at-risk districts are being conducted by the Government and health partners.

WHO risk assessment

The outbreak started on 5 September and the number of cases notified per day continues to rapidly increase, particularly in Glen View and Budiriro suburbs of Harare. Cases with epidemiological links to this outbreak have been reported from other provinces across the country. Glen View, which is the epicentre of the outbreak, is an active informal trading area where people come from across the city and the rest of the country to trade. Key risk factors for cholera in Zimbabwe include the deterioration of sanitary and health infrastructure and increasing rural-urban migration which further strains the water and sanitation infrastructure. In Harare, contaminated water from boreholes and wells is suspected to be the source of the outbreak. The water supply situation in Harare remains dire due to the high demand of water that is not being met by the city supply. The country’s available response capacities are overstretched as authorities are already responding to a large typhoid outbreak which started in August 2018. WHO assessed the overall public health risk to be high at the national level and moderate at the regional and low at global levels.

WHO advice

WHO recommends proper and timely case management in CTCs. Increasing access to potable water, improving sanitation infrastructure, and strengthening hygiene and food safety practices in affected communities are the most effective means to prevent and control cholera. Key public health communication messages should be provided to the affected population.

WHO advises against any restrictions on travel or trade to or with Zimbabwe based on the information currently available in relation to this outbreak.

For further information, please refer to:

Zimbabwe: An outbreak of cholera has so far killed 25 people, mostly in the capital, Harare.

Tuesday, September 18th, 2018“……The current outbreak began on 6 September after water wells were contaminated with sewage in Harare.

Tests found the presence of cholera and typhoid-causing bacteria which has so far infected over 3,000 people, Health Minister Obadiah Moyo told reporters on Thursday.

According to the World Health Organization (WHO), patients were not responding to first-line antibiotics……The cholera outbreak can be traced to Harare city council’s struggle to supply water to some suburbs for more than a decade, forcing residents to rely on water from open wells and community boreholes……”

WHO in Zimbabwe: 2,000 suspected cholera cases have been reported, 58 of them confirmed and 24 fatal.

Saturday, September 15th, 2018Harare/Brazzaville 13 September 2018 – The World Health Organization (WHO) is scaling up its response to an outbreak of cholera in Zimbabwe, which is expanding quickly in Harare, the country’s capital with a population of more than two million people.

Cholera is an acute waterborne diarrhoeal disease that is preventable if people have access to safe water and sanitation and practice good hygiene, but can kill within hours if left untreated. Authorities report that the outbreak began on 1 September in Harare and as of that date to 11 September, the Ministry of Health and Child Care reports that there have been nearly 2000 suspected cholera cases, including 58 confirmed cases and 24 deaths.

Glenview, a high density suburb of Harare with an active trading area and a highly mobile population is at the epicentre of the outbreak. The area is vulnerable to cholera because of inadequate supplies of safe piped water, which has led people to use alternative unsafe supplies such as wells and boreholes. Cases that are linked to the epicenter in Harare have been confirmed in 5 additional provinces.

The Government of Zimbabwe has declared a state of emergency and is working with international partners to rapidly expand recommended cholera response actions, including increasing access to clean and safe water in the most affected communities and decommissioning contaminated water supplies. Authorities and partners are also intensifying health education to ensure that suspect cases seek care immediately and establishing cholera treatment centres closer to affected communities.

“When cholera strikes a major metropolis such as Harare, we need to work fast to stop the spread of the disease before it gets out of control,” said Dr Matshidiso Moeti, the WHO Regional Director for Africa. “WHO is working closely with the national authorities and partners to urgently respond to this outbreak.”

WHO is supporting the Ministry of Health and Child Care to fight the outbreak by strengthening the coordination of the response and mobilizing national and international health experts to form a cholera surge team. In collaboration with health authorities and partners, WHO experts are helping to track down cases, providing technical support to laboratories and improving diagnostics and strengthening infection and prevention control in communities and health facilities. In addition to such measures and efforts to improve water and sanitation, the government is assessing the benefits of conducting an oral cholera vaccine (OCV) campaign and WHO is deploying an expert in OCV campaigns to Harare.

WHO is providing cholera kits which contain oral rehydration solution, intravenous fluids and antibiotics to cholera treatment centres.

Zimbabwe has experienced frequent outbreaks of cholera, with the largest outbreak occurring from August 2008 to May 2009 and claiming more than 4000 lives.

Cholera is a major public health problem in the African region and just two weeks ago Health Ministers from the region committed to ending cholera outbreaks by 2030 by implementing key strategies. Forty-seven African countries adopted the Regional Framework for the Implementation of the Global Strategy for Cholera Prevention and Control at the 68th session of WHO’s Regional Committee for Africa.

November 18, 2015–June 6, 2016: The largest cholera outbreak (1,797 cases; attack rate 5.1 per 1,000) in the history of Dadaab refugee camp in Kenya occurred.

Sunday, September 9th, 2018Golicha Q, Shetty S, Nasiblov O, et al. Cholera Outbreak in Dadaab Refugee Camp, Kenya — November 2015–June 2016. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2018;67:958–961. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.15585/mmwr.mm6734a4.

“…..During November 18, 2015–June 6, 2016, the largest cholera outbreak (1,797 cases; attack rate 5.1 per 1,000) in the history of Dadaab refugee camp in Kenya occurred. Significant risk factors included living in a compound where open defecation, visible human and solid waste, and eating from a shared plate were common. Chlorine levels in water were below standard, and handwashing facilities were insufficient…..”

WHO: Cholera and Conflict

Friday, July 6th, 2018Crisis-driven cholera resurgence switches focus to oral vaccine

Oral rehydration was once the mainstay of treatment for cholera, but today’s cholera outbreaks fuelled by conflict and instability require a new approach. Sophie Cousins reports.

Bulletin of the World Health Organization 2018;96:446-447. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.2471/BLT.18.020718

On a hot, humid afternoon at the world’s largest diarrhoeal disease hospital, dozens of patients are filing in, many being carried in the arms of loved ones, frail and barely alive.

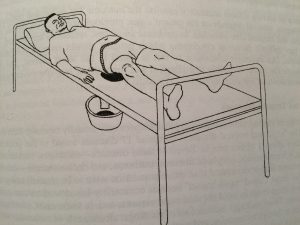

Inside the Cholera Hospital – as it is commonly known – in Dhaka, at the icddr,b (formerly the International Centre for Diarrhoeal Disease Research, Bangladesh or ICDDR, B), hundreds of patients receive rehydration treatment.

Up to 1000 patients can be admitted each day at this time of the year, as the rains peak and temperatures soar. Outside the hospital, the ward has extended into circus-size tents in the car park. Most patients recover quickly and go home within 24 hours.

“We don’t say no to anyone and we don’t charge anyone,” says Dr Azharul Islam Khan, who is the chief physician and head of hospitals at the icddr,b.

The bacterium Vibrio cholerae has wreaked havoc for hundreds of years. Originating in the Ganges delta in India, the first recorded cholera epidemic started in 1817 and travelled along trade routes through Asia and to the shores of the Caspian and Mediterranean seas. Since then, regular outbreaks across the world have killed millions of people.

Cholera is an acute diarrhoeal infection caused by ingesting food or water contaminated with Vibrio cholerae. If left untreated, the infection can kill within hours. Each year between 1.3 to 4 million cases, and up to 143 000 deaths are reported to the World Health Organization (WHO). But the true burden of cholera is unknown.

“Reporting of cholera is not reliable. The number of cholera cases reported to us is considered to be the tip of the iceberg,” says Dr Dominique Legros, from WHO’s health emergencies programme.

There are many reasons for this, he says. For one, it’s difficult to confirm cases in large outbreaks where diagnostic capacity is limited. Second, the symptoms of less severe cholera are similar to those of other diarrhoeal diseases. Third, some countries may be reluctant to report cases of cholera for fear this will affect trade or tourism, Legros adds.

Bangladesh, an impoverished country of 162 million people, where cholera is endemic, has been at the forefront of the global fight against this ancient disease.

In the past 30 years, oral rehydration solution (ORS) – a mixture of salt, sugar and clean water – has saved an estimated 50 million lives worldwide, particularly those of children who are most vulnerable to diarrhoea-related dehydration.

The simple and inexpensive mixture was first formulated to treat cholera by researchers at the icddr,b in Dhaka and their colleagues at the Johns Hopkins Center for Medical Research and Training in Kolkata, India in the late 1960s.

“ORS is the mainstay in the prevention of dehydration,” Khan says. “Bangladesh has come a long way in terms of promoting ORS and raising awareness about how to treat cholera.”

ORS has helped Bangladesh to make huge strides in improving child health in recent decades. From 1988 to 1993, diarrhoea was the cause of almost one in five deaths among children under the age of five years. Between 2007 and 2011, only 2% of these deaths were related to diarrhoea, according to the Bangladesh Demographic and health survey 2011.

Today the United Nations Children’s Fund distributes around 500 million ORS sachets a year in 60 low and middle-income countries at a cost of around US$ 0.10 each.

Yet, while ORS has saved millions of lives, cholera shows no sign of waning, even in the region where it originated. Cholera still persists for very simple reasons: a lack of access to safe water, and poor sanitation and hygiene.

For Munirul Alam, senior scientist at the Infectious Diseases Division at the icddr,b, people living in conditions of overcrowding, poor hygiene and lack of access to safe water risk contracting cholera.

Around the world, as wars, humanitarian crises and natural disasters, such as flooding and droughts, uproot millions of people, destroy basic services and health-care facilities, cholera is surging.

Cholera broke out in conflict-torn Yemen almost two years ago. It has since claimed almost 2500 lives and infected about a million people in the country of 30 million. In Nigeria, three cholera outbreaks have already been declared this year in the country’s north-east, where millions have been displaced by conflict.

If ORS is so effective in preventing death, why are people still dying of cholera? “It’s the problem of access to care,” Legros says. “Cholera starts as acute diarrhoea and can quickly become extremely severe.”

“In emergency situations, where hospitals have been destroyed, are inaccessible or lack the basic resources, people with severe dehydration do not always receive intravenous rehydration treatment that they need.”

Severely dehydrated people need the rapid administration of intravenous fluids plus ORS during treatment, along with appropriate antibiotics to reduce the duration of diarrhoea and reduce the V. cholerae in their stool.

In Yemen, Dr Nahla Arishi, paediatric co-ordinator at Alsadaqah Hospital in Aden, a port city in the south of the country, is treating up to 300 cholera cases a day.

Last year the Yemeni paediatrician travelled to Dhaka’s icddr,b to participate in a week-long training on cholera and malnutrition case management and take back the skills and knowledge to her country.

Arishi, one of a team of 20 doctors and nurses from Yemen, learnt about the assessment of dehydration, food preparation, severe acute malnutrition and observed how the Cholera Hospital manages patients.

“They will be acting as good master trainers,” Khan says, adding that the icddr,b regularly deploys its experts to assist WHO and governments with the response to diarrhoeal diseases in emergencies.

While Arishi brought knowledge home with her, there are limits in applying these lessons. Battling cholera in Yemen is extremely challenging and the situation differs from that in Bangladesh.

Alsadaqah Hospital has ORS and intravenous fluids but the provision of these simple services is constantly disrupted – disruptions that can mean a matter of life and death, she says. “Electricity is on and off and is worse in summer, [it’s the] same with water [supplies].”

In emergencies such the one in Yemen, the oral cholera vaccine is playing an increasingly important role.

Currently there are three WHO pre-qualified oral cholera vaccines, two of which are used in areas experiencing outbreaks. They require two doses at least 14 days apart and can provide protection for up to five years.

In the last five years the use of these vaccines has increased exponentially, Legros says. The reason being that the vaccine is available, easy to use, well tolerated and addresses “a disease which people fear a lot.” “If you come with a vaccine, people will take it,” he says.

In 2013, WHO established a stockpile of two million doses of oral vaccine financed by Gavi, the Vaccine Alliance, to respond to cholera outbreaks and to reduce the risk of outbreaks in humanitarian crises.

These settings include refugee camps, such as those for the Rohingyas in south-eastern Bangladesh, where two vaccination campaigns were completed between October and November 2017 and in May of this year.

The oral cholera vaccine has also been deployed in outbreaks in Haiti, Iraq and South Sudan, and recently in Malawi and Uganda.

“We’ve just started using the vaccine as a first stop for sustainable cholera control, followed up with water, sanitation and hygiene (WASH) interventions,” Legros says, referring to WASH measures that include improved water supply and sanitation, provision of safe drinking water and handwashing with soap.

But, Firdausi Qadri, a vaccine scientist and acting senior director of icddr,b’s Infectious Diseases Division, warns there aren’t enough vaccines stockpiled.

Last year an ambitious strategy to reduce cholera deaths by 90% by 2030 was launched by the Global Task Force on Cholera Control, a partnership of more than 30 health and development organizations including WHO, established in 2011.

According to Ending cholera: a global roadmap to 2030, which targets 47 countries, prevention and control can be achieved by taking a multisectoral approach and by combining the use of oral cholera vaccines with basic water, sanitation and hygiene services in addition to strengthening health-care systems and surveillance and reporting.

The roadmap also calls for a focus on cholera “hotspots,” places that are most affected by cholera – like the high risk areas in Bangladesh – that play an important role in the spread of cholera to other regions.

Bangladesh now has plans for a more systematic prevention and control of cholera, in line with the global strategy. To boost oral cholera vaccine supplies in the country, a local company is producing a vaccine, via technology transfer from India, and this could result in up to 50 million doses a year for the country, Qadri says.

But she recognizes that greater reliance on the vaccine will come at the expense of investing in water and sanitation hygiene services.

“Water, sanitation and hygiene interventions are what we need,” she says. “We have to change the whole environment and we have to educate people.”

Dr Khairul Islam, country director of WaterAid Bangladesh, agrees.

“No one would disagree that water, sanitation and hygiene interventions are ultimately the best way to prevent cholera and other water-borne gastrointestinal diseases,” he says.