Archive for the ‘Ciguatera’ Category

EPA Registers the Wolbachia ZAP Strain in Live Male Asian Tiger Mosquitoes in order to reduce their population thereby reducing the spread numerous diseases of significant human health concern

Thursday, November 9th, 2017

For Release: November 7, 2017

On November 3, 2017, EPA registered a new mosquito biopesticide – ZAP Males® – that can reduce local populations of the type of mosquito (Aedes albopictus, or Asian Tiger Mosquitoes) that can spread numerous diseases of significant human health concern, including the Zika virus.

ZAP Males® are live male mosquitoes that are infected with the ZAP strain, a particular strain of the Wolbachia bacterium. Infected males mate with females, which then produce offspring that do not survive. (Male mosquitoes do not bite people.) With continued releases of the ZAP Males®, local Aedes albopictus populations decrease. Wolbachia are naturally occurring bacteria commonly found in most insect species.

This time-limited registration allows MosquitoMate, Inc. to sell the Wolbachia-infected male mosquitoes for five years in the District of Columbia and the following states: California, Connecticut, Delaware, Illinois, Indiana, Kentucky, Massachusetts, Maine, Maryland, Missouri, New Hampshire, New Jersey, Nevada, New York, Ohio, Pennsylvania, Rhode Island, Tennessee, Vermont, and West Virginia. Before the ZAP Males® can be used in each of those jurisdictions, it must be registered in the state or district.

When the five-year time limit ends, the registration will expire unless the registrant requests further action from EPA.

EPA’s risk assessments, along with the pesticide labeling, EPA’s response to public comments on the Notice of Receipt, and the proposed registration decision, can be found on www.regulations.gov under docket number EPA-HQ-OPP-2016-0205.

CDC recommendations to healthcare providers treating patients in Puerto Rico and USVI, as well as those treating patients in the continental US who recently traveled in hurricane-affected areas during the period of September 2017 – March 2018.

Wednesday, October 25th, 2017Advice for Providers Treating Patients in or Recently Returned from Hurricane-Affected Areas, Including Puerto Rico and US Virgin Islands

Distributed via the CDC Health Alert Network

October 24, 2017, 1330 ET (1:30 PM ET)

CDCHAN-00408

Summary

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) is working with federal, state, territorial, and local agencies and global health partners in response to recent hurricanes. CDC is aware of media reports and anecdotal accounts of various infectious diseases in hurricane-affected areas, including Puerto Rico and the US Virgin Islands (USVI). Because of compromised drinking water and decreased access to safe water, food, and shelter, the conditions for outbreaks of infectious diseases exist.

The purpose of this HAN advisory is to remind clinicians assessing patients currently in or recently returned from hurricane-affected areas to be vigilant in looking for certain infectious diseases, including leptospirosis, dengue, hepatitis A, typhoid fever, vibriosis, and influenza. Additionally, this Advisory provides guidance to state and territorial health departments on enhanced disease reporting.

Background

Hurricanes Irma and Maria made landfall in Puerto Rico and USVI in September 2017, causing widespread flooding and devastation. Natural hazards associated with the storms continue to affect many areas. Infectious disease outbreaks of diarrheal and respiratory illnesses can occur when access to safe water and sewage systems are disrupted and personal hygiene is difficult to maintain. Additionally, vector borne diseases can occur due to increased mosquito breeding in standing water; both Puerto Rico and USVI are at risk for outbreaks of dengue, Zika, and chikungunya.

Health care providers and public health practitioners should be aware that post-hurricane environmental conditions may pose an increased risk for the spread of infectious diseases among patients in or recently returned from hurricane-affected areas; including leptospirosis, dengue, hepatitis A, typhoid fever, vibriosis, and influenza. The period of heightened risk may last through March 2018, based on current predictions of full restoration of power and safe water systems in Puerto Rico and USVI.

In addition, providers in health care facilities that have experienced water damage or contaminated water systems should be aware of the potential for increased risk of infections in those facilities due to invasive fungi, nontuberculous Mycobacterium species, Legionella species, and other Gram-negative bacteria associated with water (e.g., Pseudomonas), especially among critically ill or immunocompromised patients.

Cholera has not occurred in Puerto Rico or USVI in many decades and is not expected to occur post-hurricane.

Recommendations

These recommendations apply to healthcare providers treating patients in Puerto Rico and USVI, as well as those treating patients in the continental US who recently traveled in hurricane-affected areas (e.g., within the past 4 weeks), during the period of September 2017 – March 2018.

- Health care providers and public health practitioners in hurricane-affected areas should look for community and healthcare-associated infectious diseases.

- Health care providers in the continental US are encouraged to ask patients about recent travel (e.g., within the past 4 weeks) to hurricane-affected areas.

- All healthcare providers should consider less common infectious disease etiologies in patients presenting with evidence of acute respiratory illness, gastroenteritis, renal or hepatic failure, wound infection, or other febrile illness. Some particularly important infectious diseases to consider include leptospirosis, dengue, hepatitis A, typhoid fever, vibriosis, and influenza.

- In the context of limited laboratory resources in hurricane-affected areas, health care providers should contact their territorial or state health department if they need assistance with ordering specific diagnostic tests.

- For certain conditions, such as leptospirosis, empiric therapy should be considered pending results of diagnostic tests— treatment for leptospirosis is most effective when initiated early in the disease process. Providers can contact their territorial or state health department or CDC for consultation.

- Local health care providers are strongly encouraged to report patients for whom there is a high level of suspicion for leptospirosis, dengue, hepatitis A, typhoid, and vibriosis to their local health authorities, while awaiting laboratory confirmation.

- Confirmed cases of leptospirosis, dengue, hepatitis A, typhoid fever, and vibriosis should be immediately reported to the territorial or state health department to facilitate public health investigation and, as appropriate, mitigate the risk of local transmission. While some of these conditions are not listed as reportable conditions in all states, they are conditions of public health importance and should be reported.

For More Information

- General health information about hurricanes and other tropical storms: https://www.cdc.gov/disasters/hurricanes/index.html

- Information about Hurricane Maria: https://www.cdc.gov/disasters/hurricanes/hurricane_maria.html

- Information for Travelers:

- Travel notice for Hurricanes Irma and Maria in the Caribbean: https://wwwnc.cdc.gov/travel/notices/alert/hurricane-irma-in-the-caribbean

- Health advice for travelers to Puerto Rico: https://wwwnc.cdc.gov/travel/destinations/traveler/none/puerto-rico?s_cid=ncezid-dgmq-travel-single-001

- Health advice for travelers to the U.S. Virgin Islands: https://wwwnc.cdc.gov/travel/destinations/traveler/none/usvirgin-islands?s_cid=ncezid-dgmq-travel-leftnav-traveler

- Resources from CDC Health Information for International Travel 2018 (the Yellow Book):

- Post-travel Evaluation: https://wwwnc.cdc.gov/travel/yellowbook/2018/post-travel-evaluation/general-approach-to-the-returned-traveler

- Information about infectious diseases after a disaster: https://www.cdc.gov/disasters/disease/infectious.html

- Dengue: https://www.cdc.gov/dengue/index.html

- Hepatitis A: https://www.cdc.gov/hepatitis/HAV/index.htm

- Leptospirosis: https://www.cdc.gov/leptospirosis/

- Typhoid fever: https://www.cdc.gov/typhoid-fever/index.html

- Vibriosis: https://www.cdc.gov/vibrio/index.html

- Information about other infectious diseases of concern:

- Conjunctivitis: https://www.cdc.gov/conjunctivitis/

- Influenza: https://www.cdc.gov/flu/index.htm

- Scabies: https://www.cdc.gov/parasites/scabies/index.html

- Tetanus and wound management: https://www.cdc.gov/disasters/emergwoundhcp.html

- Tetanus in Areas Affected by a Hurricane: Guidelines for Clinicians https://emergency.cdc.gov/coca/cocanow/2017/2017sept12.asp

For the first time on the Indian subcontinent, an outbreak of ciguatera was reported in Mangaluru, where more than 100 people were sickened Saturday after consuming fish heads.

Tuesday, October 4th, 2016Outbreak News Today

“… the risk of additional outbreaks stems from a number of factors such as climate change, ocean acidification resulting in coral reef deterioration, nutrient run-off resulting in toxic algal blooms….”

Ciguatera poisoning? At least 15 individuals, including 9 tourists, were brought to the Commonwealth Health Center (Saipan) last week, 3 hours after they had barracuda at a Chinese restaurant..

Tuesday, March 1st, 2016Marianas Variety : Micronesia’s Leading Newspaper since 1972

CDC: Cluster of Ciguatera Fish Poisoning — North Carolina, 2007

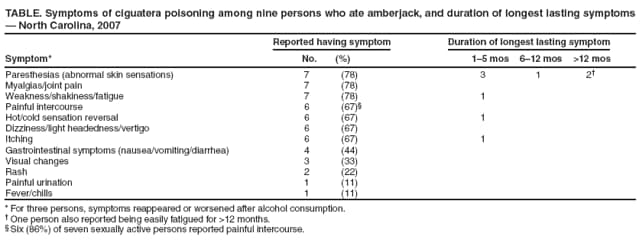

Ciguatera fish poisoning (CFP) is a distinctive type of foodborne disease that results from eating predatory ocean fish contaminated with ciguatoxins. As many as 50,000 cases are reported worldwide annually, and the condition is endemic in tropical and subtropical regions of the Pacific basin, Indian Ocean, and Caribbean. In the United States, 5–70 cases per 10,000 persons are estimated to occur yearly in ciguatera-endemic states and territories (1). CFP can cause gastrointestinal symptoms (nausea, vomiting, abdominal cramps, or diarrhea) within a few hours of eating contaminated fish. Neurologic symptoms, with or without gastrointestinal disturbance, can include fatigue, muscle pain, itching, tingling, and (most characteristically) reversal of hot and cold sensation. This report describes a cluster of nine cases of CFP that occurred in North Carolina in June 2007. Among the nine patients, six experienced reversal of hot and cold sensations, five had neurologic symptoms only, and overall symptoms persisted for more than 6 months in three patients. Among seven patients who were sexually active, six patients also complained of painful intercourse. This report highlights the potential risks of eating contaminated ocean fish. Local and state health departments can train emergency and urgent care physicians in the recognition of CFP and make them aware that symptoms can persist for months to years.

On June 28, 2007, a woman and her husband (the index couple), both aged 31 years, were treated at a hospital emergency department for illness that developed within 24 hours after eating amberjack fish purchased from a local fish market and cooked at their home. Diagnoses of CFP were based on symptoms of mild diarrhea 4–12 hours after eating fish, followed by reversal of hot and cold sensation, abnormal skin sensations, and other neurologic symptoms within 24 hours. Both patients improved after treatment with intravenous mannitol, a long-standing treatment for CFP neurologic symptoms. Upon notification, investigators from the Food and Drug Protection Division of the North Carolina Department of Agriculture and Consumer Services contacted the fish market that sold the amberjack filets and discovered that seven of eight persons at a local dinner party also had become ill after eating amberjack from the same shipment. The one person who did not become ill was a young child who did not eat any fish.

For the subsequent investigation, a case was defined as illness with gastrointestinal or neurologic symptoms within 72 hours of eating amberjack purchased at the fish market in June 2007. The nine patients whose illnesses met the case definition included three males and six females, aged 31–44 years (median: 37 years). Patients became ill 4–48 hours (median: 12 hours) after eating the fish. Abnormal skin sensations, joint pains, or weakness, shakiness, or fatigue affected seven patients (Table). For three persons, symptoms reappeared or worsened after alcohol consumption. Six of seven sexually active patients (two males and four females) also reported painful intercourse as a symptom. Both males described painful ejaculation with intercourse. One male stated that ejaculation was painful during the course of 1 week; the duration of the second male’s genitourinary symptoms was not reported. All four females described having a burning sensation during intercourse and 15 minutes to 3 hours after intercourse. Two females reported that burning sensations associated with intercourse continued for 1 month. Severity of illness could not be related to the amount of amberjack consumed nor to the incubation period.

Symptoms (i.e., abnormal skin sensations, itching, fatigue, or altered heat-cold sensation) lasted at least 1 month in all nine patients, but cleared within 6 months in six of the patients (Table). Abnormal skin sensations persisted for 6–12 months in one of the nine patients; 1 year after onset of their CFP illnesses, two of the nine patients were still experiencing occasional symptoms of abnormal skin sensations, and one of those two was easily fatigued.

Samples of cooked amberjack were sent to the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) Gulf Coast Seafood Laboratory in Dauphin Island, Alabama, for ciguatoxin analysis. Acetone extracts of fish tissue were analyzed for ciguatera-related toxins using the sodium channel-specific mouse neuroblastoma assay with Caribbean ciguatoxin-1 (C-CTX-1) as a standard (2). A level of 0.6 ng C-CTX-1 equivalents per gram (0.6 ppb) of fish flesh was found in both fish samples, and C-CTX-1 was confirmed by liquid chromatography/mass spectrometry.

The first female patient had become symptomatic within 24 hours of eating the fish. She proactively collected, stored frozen, and submitted four breast milk samples for testing at the FDA laboratory because she was breastfeeding her infant and, upon researching CFP on the Internet and speaking with a Florida physician who had treated cases of CFP, had learned that breast milk might be a transmission vehicle. Against medical advice, she continued to breastfeed, but her infant, aged 8 months, exhibited no observable adverse effects. She collected one of the breast milk samples previous to eating the amberjack and the other samples at 1, 2, and 5 days after eating the fish. No activity of C-CTX-1 was reported by the FDA laboratory in any of the breast milk samples.

Traceback of the fish responsible for this cluster of CFP cases revealed that the fish was shipped to the local fish market via a seafood distributor in Atlanta, Georgia. The amberjack had been caught off the Islamorada Hump in the Florida Keys.

Editorial Note:

Ciguatoxins are lipid-soluble cyclic polyether compounds and are the most potent sodium channel toxins known (3). Carnivorous tropical and semitropical fish, such as barracuda, amberjack, red snapper, and grouper, become contaminated with ciguatoxins by feeding on plant-eating fish that have ingested Gambierdiscus toxicus or another member of the Gambierdiscus genus, a group of large dinoflagellates commonly found in coral reef waters (4). Gambiertoxins from Gambierdiscus spp. are converted into more potent lipid-soluble ciguatoxins. Spoilage of fish that have been caught is not a factor in toxin development, and cooking does not deactivate the toxin. Humans who eat contaminated predatory fish are exposed to variable concentrations of ciguatoxin, depending on the fish size, age, and part consumed (toxins concentrate more in the viscera, especially liver, spleen, gonads, and roe). The attack rate can be as high as 80% to 90% in persons who eat affected fish, depending on the amount of toxin in the fish.

This cluster of CFP cases was unusual because six of the seven sexually active patients, two males and four females, reported onset of painful intercourse beginning in the first few days after onset of illness. Sexual transmission of ciguatoxin has been documented (5), and painful intercourse has been reported (6); however, painful intercourse is not commonly described as a consequence of CFP. Because all of the patients ate fish and developed other symptoms of CFP hours and days before experiencing painful intercourse, transmission through sexual intercourse was not considered likely in this cluster.

Persistence or recurrence of neurologic symptoms are hallmarks of CFP. Three of the nine patients in this cluster had recurrences of one or more symptoms for more than 6 months after their initial illness. If these patients are again exposed to fish (either ciguatoxin-contaminated or even noncontaminated fish), their symptoms likely will be more severe than those experienced with their initial episodes of CFP (3).

Variations in the geographic distribution of the various ciguatoxins might explain regional differences in symptom patterns. CFP symptoms associated with eating fish from the Pacific Ocean are primarily neurologic, and symptoms associated with eating fish from the Caribbean Sea are more commonly gastrointestinal (4). Amberjack often is linked to CFP cases in the Caribbean. Although the amberjack fish responsible for this cluster of CFP cases tested positive for C-CTX-1, it was not tested for the presence of other ciguatoxins, which also might have been present and could have altered disease presentation (7).

CFP has been associated almost exclusively with eating fish caught in tropical or semitropical waters, but increased global marketing of these species has increased the possibility that persons in temperate zones might become ill with CFP (4). Moreover, warming seawaters might expand the ranges of ciguatoxin-contaminated fish (8). In the United States, such fish have been found as far north as the coastal waters of North Carolina. Despite underreporting, CFP now is considered one of the most common illnesses related to fish consumption in the United States (9).

Any level of Caribbean ciguatoxin >0.1 ppb of fish tissue is thought to pose a health risk (3).* As this illness becomes more common in nontropical areas of the world, clinicians need to be aware of its manifestations and how to manage it. Although opinions vary on the most effective course of treatment, intravenous mannitol has been a mainstay of management of neurologic symptoms for more than 20 years. Early mannitol treatment is considered more effective, but anecdotal evidence suggests that even delayed therapy benefits some patients. Amitriptyline also has been useful in relieving some of the neurologic symptoms of CFP (10). If evaluating a possible case, clinicians should consult their local poison control center for the latest treatment guidelines.

References

- Gessner B, Mclaughlin J. Epidemiologic impact of toxic episodes: neurotoxic toxins. In: Botana LM, ed. Seafood and freshwater toxins pharmacology, physiology, and detection. Boca Raton, FL: CRC Press; 2008:77–104.

- Manger RL, Leja LS, Lee SY, Hungerford JM, Wekell MW. Tetrazolium-based cell bioassay for neurotoxins active on voltage-sensitive sodium channels: semiautomated assay for saxitoxins, brevetoxins, and ciguatoxins. Anal Biochem 1993;214:190–4.

- Pearn J. Neurology of ciguatera. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 2001;70:4–8.

- Lewis RJ. The changing face of ciguatera. Toxicon 2001;39:97–106.

- Lange WR, Lipkin KM, Yang GC. Can ciguatera be a sexually transmitted disease? Clin Toxicol 1989;27:193–7.

- Geller RJ, Olson KR, Senecal PE. Ciguatera fish poisoning in San Francisco, California, caused by imported barracuda. West J Med 1991;155:639–42.

- Lewis RJ, Jones A. Characterization of ciguatoxins and ciguatoxin congeners present in ciguateric fish by gradient reverse-phase high-performance liquid chromatography/mass spectrometry. Toxicon 1997;35:159–68.

- Chateau-Defat ML, Chinain M, Cerf N, Gingras S, Hubert B, Dewailly E. Seawater temperature, Gambierdiscus spp. Variability and incidence of ciguatera poisoning in French Polynesia. Harmful Algae 2005;4:1053–62.

- CDC. Surveillance for foodborne-disease outbreaks—United States, 1998–2002. MMWR 2006;55(No. SS-10).

- Lewis R, Ruff T. Ciguatera: ecological, clinical, and socioeconomic perspectives. Crit Rev Environ Sci Technol 1993;23:137–56.

* FDA has proposed guidance levels of >0.1 ppb Caribbean ciguatoxin (C-CTX-1 equivalents) and >0.01 ppb Pacific ciguatoxin (P-CTX-1 equivalents) for the 4th edition of its Fish and Fishery Products Hazards and Controls Guidance.