Archive for the ‘Food-borne diseases’ Category

Vietnam: Test results showed that methanol-tainted alcohol is the cause behind the mass food poisoning that killed seven people and 31 others hospitalized in the northern mountainous province of Lai Chau earlier this week

Sunday, February 19th, 2017CDC/FDA: The incidence of US disease outbreaks related to imported food has increased in recent years, with fish and produce most commonly implicated.

Saturday, February 18th, 2017Outbreaks of Disease Associated with Food Imported into the United States, 1996–2014

| EID | Gould L, Kline J, Monahan C, Vierk K. Outbreaks of Disease Associated with Food Imported into the United States, 1996–2014. Emerg Infect Dis. 2017;23(3):525-528. https://dx.doi.org/10.3201/eid2303.161462 |

|---|---|

| AMA | Gould L, Kline J, Monahan C, et al. Outbreaks of Disease Associated with Food Imported into the United States, 1996–2014. Emerging Infectious Diseases. 2017;23(3):525-528. doi:10.3201/eid2303.161462. |

| APA | Gould, L., Kline, J., Monahan, C., & Vierk, K. (2017). Outbreaks of Disease Associated with Food Imported into the United States, 1996–2014. Emerging Infectious Diseases, 23(3), 525-528. https://dx.doi.org/10.3201/eid2303.161462. |

Abstract

The proportion of US food that is imported is increasing; most seafood and half of fruits are imported. We identified a small but increasing number of foodborne disease outbreaks associated with imported foods, most commonly fish and produce. New outbreak investigation tools and federal regulatory authority are key to maintaining food safety.

Approximately 19% of food consumed in the United States is imported, including ≈97% of fish and shellfish, ≈50% of fresh fruits, and ≈20% of fresh vegetables (1). The proportion of food that is imported has increased steadily over the past 20 years because of changing consumer demand for a wider selection of food products and increasing demand for produce items year round (1).

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) defines a foodborne disease outbreak as the occurrence of >2 persons with a similar illness resulting from ingestion of a common food (2). Local, state, and territorial health departments report foodborne disease outbreaks to CDC through the Foodborne Disease Outbreak Surveillance System. The information collected for each outbreak includes etiology (confirmed or suspected on the basis of predefined criteria) (2), year, month, state, implicated food, and number of illnesses, hospitalizations, and deaths. Information is also collected on where implicated food originated. During 1973–1997, this information was reported anecdotally in the report’s comments section. During 1998–2008, “contaminated food imported into U.S.” was included as a location where food was prepared. Since 2009, the form has included a variable to indicate whether an implicated food was imported into the United States and the country of origin.

We reviewed outbreak reports to identify outbreaks associated with an imported food from the inception of the surveillance system in 1973 through 2014, the most recent year for which data were available. We obtained additional data for some outbreaks (e.g., country of origin) from the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) and the US Department of Agriculture Food Safety and Inspection Service.

We categorized implicated foods by using the schema developed by the Interagency Food Safety Analytics Collaboration (3). We grouped countries using the United Nations Statistics Division classification (4). We conducted a descriptive analysis of the number of outbreaks over time, by food category, and by region of origin.

Figure

Figure(https://wwwnc.cdc.gov/eid/article/23/3/16-1462-f1). Number of outbreaks caused by imported foods and total number of outbreaks with a food reported, United States, 1996–2014. Reporting practices changed over time; 1973–1997, imported foods anecdotally noted in report…

Figure(https://wwwnc.cdc.gov/eid/article/23/3/16-1462-f1). Number of outbreaks caused by imported foods and total number of outbreaks with a food reported, United States, 1996–2014. Reporting practices changed over time; 1973–1997, imported foods anecdotally noted in report…

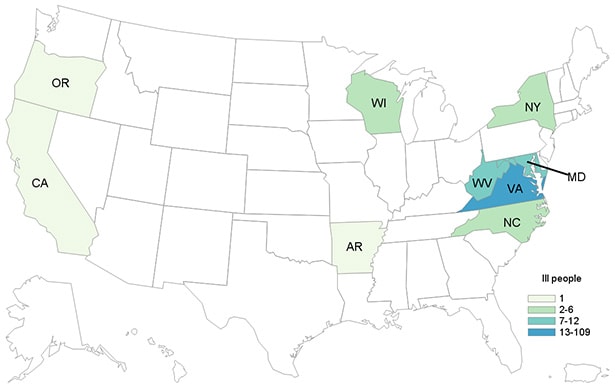

During 1996–2014, a total of 195 outbreak investigations implicated an imported food, resulting in 10,685 illnesses, 1,017 hospitalizations, and 19 deaths. Outbreaks associated with imported foods represented an increasing proportion of all foodborne disease outbreaks where a food was implicated and reported (1% during 1996–2000 vs. 5% during 2009–2014). The number of outbreaks associated with an imported food increased from an average of 3 per year during 1996–2000 to an average of 18 per year during 2009–2014 (Figure).

The most common agents reported in outbreaks associated with imported foods were scombroid toxin and Salmonella; most illnesses were associated with Salmonella and Cyclospora (Table(https://wwwnc.cdc.gov/eid/article/23/3/16-1462-t1)). Aquatic animals were responsible for 55% of outbreaks and 11% of outbreak-associated illnesses. Produce was responsible for 33% of outbreaks and 84% of outbreak-associated illnesses. Outbreaks attributed to produce had a median of 40 illnesses compared with a median of 3 in outbreaks attributed to aquatic animals. All but 1 of the outbreaks caused by scombroid toxin was associated with fish. Most of the Salmonella outbreaks (77%) were associated with produce, including fruits (n = 14), seeded vegetables (n = 10), sprouts (n = 6), nuts and seeds (n = 5), spices (n = 4), and herbs (n = 1).

Information was available on the region of origin for 177 (91%) outbreaks. Latin America and the Caribbean was the most common region implicated, followed by Asia (Technical Appendix(https://wwwnc.cdc.gov/eid/article/23/3/16-1462-techapp1.xlsx)). Thirty-one countries were implicated; Mexico was most frequently implicated (42 outbreaks). Other countries associated with >10 outbreaks were Indonesia (n = 17) and Canada (n = 11). Fish and shellfish originated from all regions except Europe but were most commonly imported from Asia (65% of outbreaks associated with fish or shellfish). Produce originated from all regions but was most commonly imported from Latin America and the Caribbean (64% of outbreaks associated with produce). All but 1 outbreak associated with dairy products involved products imported from Latin America and the Caribbean.

Outbreaks in this analysis were reported from 31 states, most commonly California (n = 30), Florida (n = 25), and New York (n = 16). Forty-three outbreaks (22%) were multistate outbreaks.

The number of reported outbreaks associated with imported foods, although small, has increased as an absolute number and in proportion to the total number of outbreaks in which the implicated food was identified and reported. Although many types of imported foods were associated with outbreaks, fish and produce were most common. These findings are consistent with overall trends in food importation (5).

Many outbreaks, particularly outbreaks involving produce, were associated with foods imported from countries in Latin America and the Caribbean. Because of their proximity, these countries are major sources of perishable items such as fresh fruits and vegetables; Mexico is the source of about one quarter of the total value of fruit and nut imports and 45%–50% of vegetable imports, followed by Chile and Costa Rica. Similarly, our finding that many outbreaks were associated with fish from Asia is consistent with data on the sources of fish imports (6).

One quarter of the outbreaks were multistate, reflecting the wide distribution of many imported foods. Systems like PulseNet have helped to improve detection and investigation of multistate outbreaks, resulting in an increased number of multistate outbreaks (7,8). The increasing number of outbreaks involving globally distributed foods underscores the need to strengthen regional and global networks for outbreak detection and information sharing. The importance of having standard protocols for molecular characterization of isolates and systems for rapid traceability of implicated foods to their source was illustrated during the investigation of a listeriosis outbreak linked to Italian cheese imported into the United States in 2012 (9). Newer tools like whole genome sequencing can also help to generate hypothetical transmission networks and in some instances facilitate traceback of foods to their origin (10). Moreover, new tools that aid visualization of supplier networks facilitate the investigation of outbreaks involving the increasingly complex global economy (11).

Nearly all of the outbreaks involved foods under FDA jurisdiction. Only a small proportion of FDA-regulated foods are inspected upon entry into the United States. New rules under the Food Safety Modernization Act of 2011, including the Preventive Controls Rule for Human Food, Produce Safety Rule, Foreign Supplier Verification Program, and Accreditation of Third Party Auditors, will help to strengthen the safety of imported foods by granting FDA enhanced authorities to require that imported foods meet the same safety standards as foods produced domestically (12).

Although data collection has improved in recent years, these findings might underestimate the number of outbreaks associated with imported foods because the origin of only a small proportion of foods causing outbreaks is reported. Similarly, because of how data are collected and reported, the relative safety of imported and domestically produced foods cannot be compared. Because of changes in surveillance and changing import patterns, changes over time should be interpreted cautiously.

Our findings reflect current patterns in food imports and provide information to help guide future outbreak investigations. Prevention focused on the most common imported foods causing outbreaks, produce and seafood, could help prevent outbreaks. Efforts to improve the safety of the food supply can include strengthening reporting by gathering better data on the origin of implicated food items, including whether imported and from what country.

Dr. Gould served as a team lead in the Enteric Diseases Epidemiology Branch, Division of Foodborne, Waterborne, and Environmental Diseases, National Center for Emerging and Zoonotic Infectious Diseases, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Her research interests focus on ways to improve surveillance for foodborne illness and understanding the impact of changes in food production on outbreaks and illnesses.

References

- US Department of Agriculture. Import share of consumption. 2016 [cited 2016 Aug 12]. http://www.ers.usda.gov/topics/international-markets-trade/us-agricultural-trade/import-share-of-consumption.aspx

- Gould LH, Walsh KA, Vieira AR, Herman K, Williams IT, Hall AJ, et al.; Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Surveillance for foodborne disease outbreaks – United States, 1998-2008. MMWR Surveill Summ. 2013;62:1–34.PubMed

- Interagency Food Safety Analytics Collaboration. Completed projects: improve the food categories used to estimate attribution [cited 2015 Nov 5]. http://www.cdc.gov/foodsafety/ifsac/projects/completed.html

- United Nations Statistics Division. Composition of macro geographical (continental) regions, geographical sub-regions, and selected economic and other groupings [cited 2015 Sep 15]. http://unstats.un.org/unsd/methods/m49/m49regin.htm#americas

- Brooks N, Regmi A, Jerardo AUS. food import patterns, 1998–2007 [cited 2015 Sep 15]. https://naldc.nal.usda.gov/download/32182/PDF

- US Department of Agriculture. U.S. Agricultural trade: imports [cited 2015 Nov 5]. http://www.ers.usda.gov/topics/international-markets-trade/us-agricultural-trade/imports.aspx

- Crowe SJ, Mahon BE, Vieira AR, Gould LH. Vital Signs: multistate foodborne outbreaks—United States, 2010–2014. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2015;64:1221–5. DOIPubMed

- Nguyen VD, Bennett SD, Mungai E, Gieraltowski L, Hise K, Gould LH. Increase in multistate foodborne disease outbreaks—United States, 1973–2010. Foodborne Pathog Dis. 2015;12:867–72. DOIPubMed

- Acciari VA, Iannetti L, Gattuso A, Sonnessa M, Scavia G, Montagna C, et al. Tracing sources of Listeria contamination in traditional Italian cheese associated with a US outbreak: investigations in Italy. Epidemiol Infect. 2016;144:2719–27. DOIPubMed

- Hoffmann M, Luo Y, Monday SR, Gonzalez-Escalona N, Ottesen AR, Muruvanda T, et al. Tracing origins of the Salmonella Bareilly strain causing a food-borne outbreak in the United States. J Infect Dis. 2016;213:502–8. DOIPubMed

- Weiser AA, Gross S, Schielke A, Wigger JF, Ernert A, Adolphs J, et al. Trace-back and trace-forward tools developed ad hoc and used during the STEC O104:H4 outbreak 2011 in Germany and generic concepts for future outbreak situations. Foodborne Pathog Dis. 2013;10:263–9. DOIPubMed

- US Food and Drug Administration. FDA Issues Two Proposed Rules under FSMA to strengthen the oversight of imported foods [cited 2015 Nov 5]. http://www.fda.gov/Food/NewsEvents/ConstituentUpdates/ucm362532.htm

Figure

Table

Technical Appendix

1Preliminary results from this study were presented at the International Conference on Emerging Infectious Diseases, March 11–14, 2012, Atlanta, Georgia, USA.

2Current affiliation: New York City Department of Mental Health and Hygiene, Queens, New York, USA.

Association of acute toxic encephalopathy with litchi consumption in an outbreak in Muzaffarpur, India, 2014

Wednesday, February 1st, 2017litchii-encephalopathy_lancet-2017

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=uAubUZ6pdoE

Un plat de poisson servi avec de la mayonnaise

Friday, November 18th, 2016Food poisoning among French prisoners

- A dish of fish served with mayonnaise could be the cause

- Affected about 100 detainees out of approximately 260

Multistate outbreak of hepatitis A linked to frozen strawberries: Update

Sunday, October 23rd, 2016Multistate Outbreak of Shiga toxin-producing Escherichia coli O157:H7 Infections Linked to Beef Products Produced by Adams Farm

Tuesday, September 27th, 2016CDC, multiple states, and the U.S. Department of Agriculture Food Safety and Inspection Service (USDA-FSIS) are investigating a multistate outbreak of Shiga toxin-producing Escherichia coli(http://www.cdc.gov/ecoli/general/index.html)O157:H7 (STEC O157:H7) infections.

- Seven people infected with the outbreak strain of STEC O157:H7 have been reported from four states.

- Five ill people have been hospitalized. No one has developed hemolytic uremic syndrome, a type of kidney failure, and no deaths have been reported.

At A Glance

- Case Count: 7(http://www.cdc.gov/ecoli/2016/o157h7-09-16/epi.html)

- States: 4(http://www.cdc.gov/ecoli/2016/o157h7-09-16/map.html)

- Deaths: 0

- Hospitalizations: 5

- Recall: Yes(http://www.cdc.gov/ecoli/2016/o157h7-09-16/advice-consumers.html)

Cyclospora cases linked with travel to Mexico: 204 cases reported in the UK since 1 June 2016

Sunday, August 14th, 2016Investigations are ongoing after an increase in cases of food and water bug, Cyclospora, associated with travellers returning from Mexico.

Public Health England (PHE) is advising people planning on travelling to the Riviera Maya coast in Mexico to be aware of the risk of infection from a food and water bug, Cyclospora.

PHE is aware of an increase in Cyclospora cases linked with travel to Mexico. There have been 204 cases reported in the UK since 1 June 2016, with 148 cases from holidaymakers who stayed in a number of different hotels and resorts on the Riviera Maya coast. Investigations into the source of infection are ongoing.

Infection can cause frequent, watery diarrhoea, abdominal cramping, bloating, nausea, flatulence, low-grade fever, loss of appetite and weight. Individuals with underlying immune deficiency can be at risk of more severe infection.

Travellers to Mexico are strongly advised to maintain a high standard of food, water and personal hygiene, even if staying in high-end resorts. There is no risk of the bug being passed from person to person.

Advice for travellers

Infection is transmitted through consumption of food or water that is contaminated by Cyclospora. Foods often implicated in outbreaks include soft fruits like raspberries and salad products such as coriander, basil and lettuce.

Travellers are advised to:

- ensure drinking water is bottled, boiled, or filtered with a special filter designed for purifying drinking water

- avoid uncooked berries, unpeeled fruit, salad leaves and fresh herbs since these are difficult to clean

- ensure food is freshly prepared, thoroughly cooked and eaten hot whenever possible

On return from Mexico, if you have any symptoms such as those described above you should seek medical attention and tell your GP about your travel history. The infection is diagnosed by testing of stool samples, and although most cases resolve on their own, antibiotics can be given to treat severe or prolonged infections.

Dr Katherine Russell, Head of Travel and Migrant Health at PHE, said:

Following the link with travel to Mexico, the UK travel industry has been informed and we are sharing information with the Mexican health authorities to support their investigations.

Get medical advice for any symptoms, either during your holiday or after you return. Symptoms can include: diarrhoea, appetite loss, stomach cramps and pain, bloating, increased wind, weight loss, nausea or tiredness. If you are ill when you get home, remember to tell your GPabout your travel history.

Dr Vanessa Field, Deputy Director of the National Travel Health Network and Centre (NaTHNaC), said:

It is very important to reinforce the need for travellers going to tropical or subtropical countries, including Mexico, to follow good food and water hygiene advice at all times on holiday, even if staying in high-end, all-inclusive resorts. Avoid buffets and choose recently prepared, thoroughly cooked food that is served piping hot. Avoid fresh uncooked berries or unpeeled fruit and any salad items not washed in safe water. Remember that drinks may also contain uncooked herbs, vegetables or fruit.

Cyclospora cayetanensis is a protozoan parasite that infects humans. Infection is acquired from food or water contaminated by the parasite. Because this organism is not infectious until approximately 10 days after they are passed in faeces, person-to-person transmission does not occur.

Read advice about food and water hygiene and specific advice for travellers to Mexico on the NaTHNaC website.

General information on Cyclospora is available on the NHS Choices website.

Clinical and travel guidance for health professionals is available on the PHEwebsite.

Canada: Public Health Notice – Outbreak of Cyclospora under investigation

Saturday, August 13th, 2016Public Health Agency of Canada

Why you should take note?

The Public Health Agency of Canada is collaborating with provincial public health partners, the Canadian Food Inspection Agency, and Health Canada to investigate locally-acquired Cyclospora infections in four provinces. The source of the outbreak has not been identified. Imported fresh produce products are currently items of interest in the ongoing investigation. This Notice will be updated as new information becomes available.

Cyclospora is a microscopic single-celled parasite that is passed in people’s feces. If it comes in contact with food or water, it can infect the people who consume it. This causes an intestinal illness called cyclosporiasis.

Cyclospora is not common on food and is not in drinking water in Canada. The parasite is most common in some tropical and subtropical countries such as Peru, Cuba, India, Nepal, Mexico, Guatemala, Southeast Asia and Dominican Republic. In Canada, non-travel related illnesses due to Cyclospora occur more frequently in the spring and summer months. Illnesses among travellers can happen at any time of year.

Investigation Summary

In Canada, a total of 51 cases have been reported: in British Columbia (1), Alberta (2), Ontario (44), and Quebec (4). Individuals became sick between May and July 2016. The majority of cases are male (51%), with an average age of 49 years. One case was hospitalized. The investigation into the source of the outbreak is ongoing. To date, no multi-jurisdictional outbreaks of Cyclospora have been linked to produce grown in Canada.

Previous foodborne illness outbreaks of Cyclospora in Canada and US have been linked to various types of imported fresh produce, such as pre-packaged salad mix, basil, cilantro, raspberries, blackberries, mesclun lettuce and snow and snap peas.

Who is most at risk?

People living or traveling in tropical or subtropical regions of the world who eat fresh produce or drink untreated water may be at increased risk for infection because the parasite is found in some of these regions.

Most people recover fully, however, it may take several weeks before an ill person’s intestinal problems completely disappear.

What you should do to protect your health?

It can be hard to prevent cyclosporiasis. This is because washing produce does not always get rid of the Cyclospora parasite that causes the illness. You can reduce your risk by:

- cooking produce imported from countries where Cyclospora is found; and

- consuming fresh produce grown in countries where Cyclospora is not common, such as Canada, the United States, and European countries.

When travelling to a country where Cyclospora is found, you can reduce your risk by:

- avoiding food that has been washed in local drinking water;

- drinking water from a safe source; and

- eating cooked food or fruit that you can peel yourself.

Symptoms

People infected with Cyclospora can experience a wide range of symptoms. Some do not get sick at all, while others feel as though they have a bad case of stomach flu. Few people get seriously ill.

Most people develop the following symptoms within one week after being infected with Cyclospora:

- watery diarrhea

- abdominal bloating and gas

- fatigue (tiredness)

- stomach cramps

- loss of appetite

- weight loss

- mild fever

- nausea

When you eat or drink contaminated food or water, it may take 7 to 14 days for symptoms to appear. If left untreated, you may have the symptoms for a few days up to a few months. Most people have symptoms for 6 to 7 weeks. Sometimes, symptoms may go away and then return.

If you become ill, drink plenty of water or fluids to prevent dehydration from diarrhea. If you have signs of illness and have reason to believe you have cyclosporiasis, call your health care provider.

What the Government of Canada is doing

The Government of Canada is committed to food safety. The Public Health Agency of Canada leads human health investigations of outbreaks and is in regular contact with its federal and provincial partners to monitor and take collaborative steps to address outbreaks.

Health Canada provides food-related health risk assessments to determine if the presence of a certain substance or microorganism poses a health risk to consumers.

The Canadian Food Inspection Agency (CFIA) conducts food safety investigations into the possible food source of an outbreak.

The Government of Canada will continue to update Canadians if new information related to this investigation becomes available.

Additional Information

Media Contact

Public Health Agency of Canada

Media Relations

(613) 957-2983

Public Inquiries

Call toll-free: 1-866-225-0709

Email: info@hc-sc.gc.ca

The U.S. Department of Agriculture’s Food Safety and Inspection Service (FSIS) is issuing a public health alert today due to concerns about illnesses caused by Salmonella I 4,[5],12:i:- that may be associated with use and consumption of whole hog roasters prepared for BBQ

Friday, July 22nd, 2016Recommendations for Preventing Salmonellosis:

Wash hands with soap and water for at least 20 seconds before and after handling raw meat and poultry. Also wash cutting boards, dishes and utensils with hot soapy water. Clean up spills right away.

Keep raw meat, fish and poultry away from other food that will not be cooked. Use one cutting board for raw meat, poultry and egg products and a separate one for fresh produce and cooked foods.

Cook raw meat and poultry to safe internal temperatures before eating. The safe internal for ground meat is 160º F, and 165º F for poultry, as determined with a food thermometer.

Refrigerate raw meat and poultry within two hours after purchase (one hour if temperatures exceed 90º F). Refrigerate cooked meat and poultry within two hours after cooking.