Archive for the ‘Humanitarian’ Category

World Health Worker Week: April 2-8, 2017

Sunday, April 2nd, 2017World Health Worker Week is an opportunity to mobilize communities, partners, and policy makers in support of health workers in your community and around the world. It is a time to celebrate the amazing work that they do and it is a time to raise awareness to the challenges they face every day. Perhaps most importantly, it is an opportunity to fill in the gaps in the health workforce by calling those in power to ensure that health workers have the training, supplies and support they need to do their jobs effectively.

They are caretakers. They are educators. They are your neighbors, friends, and family. Without them, there would be no health care for millions of families in the developing world.

Frontline health workers are midwives, community health workers, pharmacists, peer counselors, nurses and doctors working at community level as the first point of care for communities. They are the backbone of effective health systems and often come from the very communities they serve.

They are the first and often the only link to health care for millions of people. Frontline health workers provide immunizations and treat common infections. They are on the frontlines of battling deadly diseases diseases like Ebola and HIV/AIDS, and many families rely on them as trusted sources of information for preventing, treating and managing a variety of leading killers including diarrhea, pneumonia, malaria and tuberculosis.

Honor health workers in your community (or communities you work in) by sharing their story. Participate in our ‘#HealthWorkersCount because…’ campaign. Download our template or make your own, but share your reasons using the hashtags #WHWWeek and #HealthWorkersCount. You can also use these hashtags to participate in our WHWW Twitter Chat on April 4 at 1pm EDT.

Organize events, local advocacy campaigns and other activities calling global leaders to prioritize health workforce strengthening.

Download our World Health Worker Week Toolkit for Engagement for more ideas!

World Health Worker Week is only seven days, but here is how you can take action and make a difference year round:

Follow us on Twitter and Facebook to get updates of our activities, news and ways to get involved.

The Global Health Workforce Network operates within WHO as a global mechanism for stakeholder consultation, dialogue and coordination on comprehensive and coherent health workforce policies in support of the implementation of the Global Strategy on Human Resources for Health: Workforce 2030 and the recommendations of the High-Level Commission on Health Employment and Economic Growth.

Let your member of Congress know how important frontline health workers are to saving lives and increasing security from global health threats worldwide. Refer to our brief on the Global Health Council’s ‘Global Health Works’ Report for basic facts and recommendations to highlight your message.

Advocacy organizations like the ONE Campaign and RESULTS provide direct actions you can take to raise awareness and urge your policymakers to support US global health efforts. Get involved today and spread the word that #HealthWorkersCount.

How healthcare suffered when ISIL seized Mosul, Iraq

Saturday, April 1st, 2017CITY PROFILE OF MOSUL, IRAQ

Multi-sector assessment of a city under siege

United Nations Human Settlements Programme in Iraq (UN-Habitat) 2016

www.unhabitat.org

Nineveh Governorate was once known for its good

healthcare services and highly-qualified doctors.

Between 2008 and 2014, a substantial number of facilities

were rehabilitated and equipped with new medical

instruments. New specialized hospitals were also planned

in the northern and southern parts of the city, and some

were still under construction when ISIL took over the city

(Map 23).

According to the Ministry of Planning (2013), Mosul city

has in total:

• 13 public hospitals with a 3,200-bed capacity;

• 4 specialized public hospitals (gynaecology, cancer

and nuclear medicine, paediatric and maternity, and

chest diseases and fevers) with a 228-bed capacity;

• 3 private hospitals with a 104-bed capacity;

• 32 public health clinics; and

• 254 private health clinics.

All these facilities were managed by specialist doctors

and were working properly until ISIL occupied the city.

At that point, although hospitals were not destroyed by

air strikes and continue to receive civilian patients, health

services started to deteriorate. Due to the fragile security

situation, many medical staff members fled. This clearly

affected the quality of healthcare and the capacity of

hospitals to deal with surgical cases, and with patients

in general. With regard to surgeries, priority was given

to non-civilians patients. Also, the higher fees that ISIL

imposed on medical services and operations (IQD 100,000

– IQD 500,000) added to the suffering of many civilians.

The fact that ISIL prohibited male doctors from examining

female patients, and female doctors from examining

male patients, has particularly affected maternal health.

Exacerbating the problem is the increasingly poor

sanitation in hospitals and the disposal of hazardous

waste. The lack of obstetric and natal care is another

serious issue especially in view of the depletion of

vaccinations for infants. The availability of other medical supplies and equipment has also decreased, as stocks

were transferred outside Mosul and/or diverted for other

uses by ISIL.

The closure of the highways that connect Mosul with

other Iraqi cities further contributed to the decline of

the city’s health sector. Although many pharmacies are

still open, their stocks is quite limited. Medicines, when

available, are largely unaffordable. According to some city

residents, the only available medicines in Mosul today

are illegally imported from Syria and Turkey through ISIL

followers.

In short, many city inhabitants are affected by poor

healthcare, difficult access to surgery, unavailability of

basic medicines and medical supplies (e.g. insulin and

medicines for high blood pressure), as well as poor solid

waste disposal and limited clean water for drinking.

“Starving to death”: UN aid chief urges global action as starvation, famine loom for 20 million across Kenya, Yemen, South Sudan and Somalia

Saturday, March 11th, 2017

10 March 2017 – Just back from Kenya, Yemen, South Sudan and Somalia – countries that are facing or are at risk of famine – the top United Nations humanitarian official today urged the international community for comprehensive action to save people from simply “starving to death.”

“We stand at a critical point in history. Already at the beginning of the year we are facing the largest humanitarian crisis since the creation of the UN,” UN Emergency Relief Coordinator Stephen O’Brien told the Security Council today.

Without collective and coordinated global efforts, he warned, people risk starving to death and succumbing to disease, stunted children and lost futures, and mass displacements and reversed development gains.

“The appeal for action by the Secretary-General can thus not be understated. It was right to sound the alarm early, not wait for the pictures of emaciated dying children […] to mobilize a reaction and the funds,” Mr. O’Brien underscored, calling for accelerated global efforts to support UN humanitarian action on the ground.

Turning to the countries he visited, the senior UN official said that, about two-thirds of the population (more than 18 million people) in Yemen needed assistance, including more than seven million severely food insecure, and the fighting continued to worsen the crisis.

“I continue to reiterate the same message to all: only a political solution will ultimately end human suffering and bring stability to the region,” he said, noting that with access and funding, humanitarians will do more, but cautioned that relief-workers were “not the long-term solution to the growing crisis.”

In South Sudan, where a famine was recently declared, more than 7.5 million people are in need of assistance, including some 3.4 million displaced. The figure rose by 1.4 million since last year.

“The famine in the country is man-made. Parties to the conflict are parties to the famine – as are those not intervening to make the violence stop,” stressed Mr. O’Brien, calling on the South Sudanese authorities to translate their assurances of unconditional access into “action on the ground.”

Similarly, more than half the population of Somalia (6.2 million people) is need aid, 2.9 million of whom require immediate assistance. Extremely worrying is that more than one million children under the age of five are at the risk of acute malnourishment.

“The current indicators mirror the tragic picture of 2011, when Somalia last suffered a famine,” recalled the UN official, but expressed hope that a famine can be averted with strong national leadership and immediate and concerted support by the international community.

Concerning Kenya, he mentioned that more than 2.7 million people were food insecure, and that this number could reach four million by April.

“In collaboration with the Government [of Kenya], the UN will soon launch an appeal of $200 million to provide timely life-saving assistance and protection,” he informed.

Further in his briefing, Mr. O’Brien informed the Council of the outcomes of the Oslo Conference on the Lake Chad Basin where 14 donors pledged a total of $672 million, of which $458 million is for humanitarian action in 2017.

“This is very good news, and I commend those who made such generous pledges,” he said but noted that more was needed to fully fund the $1.5 billion required to provide the assistance needed across the region.

On the UN response in these locations, Mr. O’Brien highlighted that strategic, coordinated and prioritized plans are in place and dedicated teams on the ground are closely working with partners to ensure that immediate life-saving support reaches those in need.

“Now we need the international community and this Council to act,” he highlighted, urging prompt action to tackle the factors causing famine; committing sufficient and timely financial support; and ensuring that fighting stops.

In particular, he underscored the need to ensure that humanitarians have safe, full and unimpeded access and that parties to the conflict in the affected countries respect humanitarian law and called on those with influence over the parties to the conflict to “exert that influence now.”

“It is possible to avert this crisis, to avert these famines, to avert these looming human catastrophes,” he concluded. “It is all preventable.”

TARGETED ATTACKS ON MEDICAL FACILITIES AND STAFF IN AFGHANISTAN LEAD TO DEATH AND DISEASE AMONG CHILDREN

Thursday, March 9th, 2017For Immediate Release ***To view report: http://watchlist.org/about/report/afghanistan/ ***Link to live press conference March 6, 2017, 10:00am EST: http://www.un.org/webcast/ TARGETED ATTACKS ON MEDICAL FACILITIES AND STAFF IN AFGHANISTAN LEAD TO DEATH AND DISEASE AMONG CHILDREN

New Report Calls for Afghan Government Forces to be Cited as Responsible for Attacks for First Time

NEW YORK, March 6, 2017 – Afghan government forces, the Taliban and other parties to the country’s conflict have repeatedly targeted medical facilities and staff, negatively impacting children’s health, Watchlist on Children and Armed Conflict said in a new report today. For the first time, Watchlist called on the UN Secretary General to list the Afghan National Defense and Security Forces (ANDSF) as one of the parties responsible for these attacks. Watchlist’s 27-page report, which focuses on 2015 and 2016, details how parties to the conflict, through more than 240 attacks, have temporarily or permanently closed medical facilities throughout Afghanistan, damaged or destroyed facilities, looted medical supplies, stolen ambulances, and threatened, intimidated, extorted, detained and killed medical personnel. They have restricted and sometimes blocked access to health care and used medical facilities for military purposes, which is in violation of international humanitarian law. While the Taliban and other anti-government groups were responsible for the majority of attacks, the ANDSF carried out at least 35 attacks on medical facilities and personnel between 2015 and 2016. “Targeted attacks on medical facilities have decimated Afghanistan’s fragile health system, preventing many civilians from accessing lifesaving care,” said Christine Monaghan, research officer at Watchlist who traveled to Afghanistan in November 2016 and wrote the report. “Children suffer as a result — we are seeing more deaths, injuries and the spread of disease.”

Attacks on hospitals have compounded challenges to children’s health, already exacerbated by two years of escalating armed conflict, according to the report. In Afghanistan, 4.6 million people, including more than 2.3 million children, are in critical need of health care, according to the World Health Organization (WHO). More than 1 million children suffer from acute malnutrition, an increase of more than 40 percent since the beginning of the reporting period in January 2015, according to WHO. Communicable diseases are also up; WHO reported 169 measles outbreaks in 2015, an increase of 141 percent from 2014. The United Nations Assistance Mission in Afghanistan (UNAMA) furthermore reported that child casualties increased by 24 percent from 2015 to 2016.

Watchlist’s report includes stories from individuals impacted by the damaged health care system. One father discussed how his 15-year-old son lost both feet after stepping on a mine. He could not get proper care in Kunduz City, where the only trauma center had been bombed and many medical professionals had been killed or had fled. He eventually took a taxi to Kabul, more than 200 miles away, where he was told his son needed to get treatment earlier. “Now, both of his legs must get cut off from just below the waist, because the bones are ruined and he has a serious infection,” the father told Watchlist. “For a week he was OK, but then from the infection he went into a coma. Ten days later, he died in the hospital.”

The report calls on all parties to immediately stop attacks on medical facilities and personnel, which are protected during times of conflict under international humanitarian and human rights laws. It calls on the UN Secretary-General to list the ANDSF in its 2017 annual report on children and armed conflict, which is expected to come out before the summer. While previous UN reports included incidents by Afghan forces, the SecretaryGeneral only listed the Taliban in his annual report as responsible for attacks on hospitals. Watchlist also recommends the Afghan government establish an independent and permanent body to investigate these attacks.

About the report “Every Clinic is Now on the Frontline” The Impact on Children of Attacks on Health Care in Afghanistan Watchlist conducted a research trip in Afghanistan in November and December 2016 and interviewed more than 80 people, including humanitarian actors, health workers, health “shura” members, and patients.

Watchlist visited five hospitals and focused its research on four provinces: Helmand, Kunduz, Nangarhar and Maidan Wardak. To read the report: http://watchlist.org/about/report/afghanistan/ About Watchlist on Children and Armed Conflict Watchlist on Children and Armed Conflict is a New York-based global coalition that serves to end violations against children in armed conflict and to guarantee their rights.

For more information: http://watchlist.org/ Press Contacts: Vesna Jaksic Lowe vesnajaksic@gmail.com + 1 917.374.2273 Bonnie Berry bonnie@watchlist.org +1 212.972.0695

Response to a Large Polio Outbreak in a Setting of Conflict — Middle East, 2013–2015

Saturday, March 4th, 2017Chukwuma Mbaeyi, DDS1; Michael J. Ryan, MD2; Philip Smith, MD2; Abdirahman Mahamud, MD2; Noha Farag, MD, PhD1; Salah Haithami, MD2; Magdi Sharaf, MD2; Jaume C. Jorba, PhD3; Derek Ehrhardt, MPH, MSN1

Weekly / March 3, 2017 / 66(8);227–231

Summary

What is already known about this topic?Afghanistan, Nigeria, and Pakistan are the only three countries that have never interrupted endemic transmission of wild poliovirus (WPV). Continued WPV circulation in these countries poses a risk for polio outbreaks in polio-free regions of the world, especially in countries experiencing conflict and insecurity, with attendant disruption of health care and immunization services.

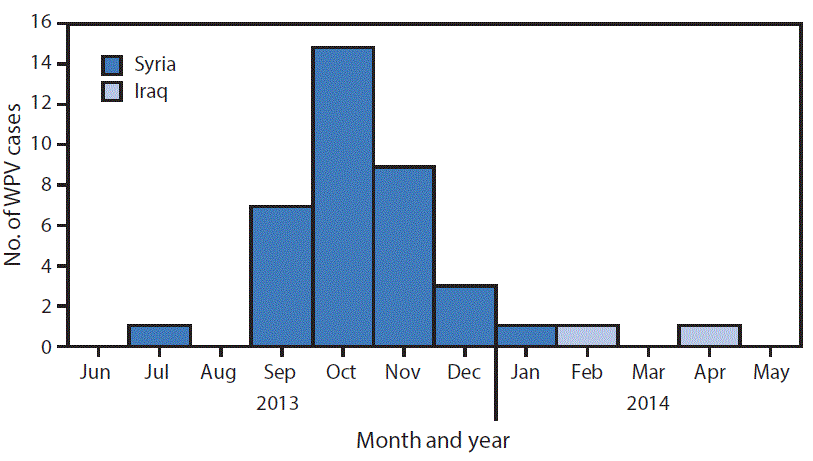

What is added by this report?A WPV outbreak occurred in Syria and Iraq during 2013–2014 after importation of a poliovirus strain circulating in Pakistan. The outbreak represented the first occurrence of polio cases in both countries in approximately a decade, and resulted in 38 polio cases, including 36 in Syria and two in Iraq. Development and implementation of an integrated response plan for strengthening acute flaccid paralysis surveillance and synchronized mass vaccination campaigns by eight national governments in the Middle East facilitated interruption of the outbreak within 6 months of its identification.

What are the implications for public health practice?Countries experiencing active conflict and chronic insecurity are at increased risk for polio outbreaks because of political instability and population displacement hindering delivery of immunization services. Adoption of a concerted approach to planning and implementing response activities, with involvement of more stable neighboring countries, could serve as a useful model for polio outbreak response in areas affected by conflict, as exemplified by the Middle East polio outbreak response.

As the world advances toward the eradication of polio, outbreaks of wild poliovirus (WPV) in polio-free regions pose a substantial risk to the timeline for global eradication. Countries and regions experiencing active conflict, chronic insecurity, and large-scale displacement of persons are particularly vulnerable to outbreaks because of the disruption of health care and immunization services (1). A polio outbreak occurred in the Middle East, beginning in Syria in 2013 with subsequent spread to Iraq (2). The outbreak occurred 2 years after the onset of the Syrian civil war, resulted in 38 cases, and was the first time WPV was detected in Syria in approximately a decade (3,4). The national governments of eight countries designated the outbreak a public health emergency and collaborated with partners in the Global Polio Eradication Initiative (GPEI) to develop a multiphase outbreak response plan focused on improving the quality of acute flaccid paralysis (AFP) surveillance* and administering polio vaccines to >27 million children during multiple rounds of supplementary immunization activities (SIAs).† Successful implementation of the response plan led to containment and interruption of the outbreak within 6 months of its identification. The concerted approach adopted in response to this outbreak could serve as a model for responding to polio outbreaks in settings of conflict and political instability.

Outbreak Detection and Epidemiology

Detection of the Middle East outbreak depended upon systems for AFP surveillance in the affected countries, including the World Health Organization’s (WHO’s) Early Warning, Alert and Response Network (EWARN)§, through which the outbreak was identified in October 2013. The nonpolio AFP (NPAFP) and stool adequacy rates served as indicators for assessing the ability of the affected countries to detect polio cases and also to determine when the outbreak had been interrupted.

Among countries that reported polio cases, the NPAFP rate in Syria in 2012 was 1.4 cases per 100,000 persons aged <15 years, below the recommended benchmark of ≥2. The NPAFP rate for Syria improved, increasing to 1.7 cases per 100,000 persons in 2013, the year the outbreak was detected, and to 4.0 and 3.0 in 2014 and 2015, respectively (Table). In Iraq, the NPAFP rate ranged from 3.1 to 4.0 during 2012–2015; estimates of NPAFP rates in Syria and Iraq might, however, be inaccurate because of the large-scale conflict-related displacement of persons and the attendant impact on target population estimates. Among countries at risk, NPAFP rates were suboptimal in Jordan at the onset, but improved over the course of the outbreak, increasing from 1.4 in 2013 to 3.2 in 2015. Despite incremental improvements, NPAFP rates remained <2 in Turkey over the course of the outbreak, and rates declined in Palestine from 2.2 in 2013 to 1.2 in 2014 before improving to 2.2 in 2015. All other countries involved in the response achieved recommended benchmarks.

Rates of stool specimen adequacy (i.e., receipt of two stool specimens collected at least 24 hours apart within 14 days of paralysis onset and properly shipped to the laboratory) in Syria increased from 68% in 2013 to 90% in 2015; in Iraq, rates of stool specimen adequacy exceeded the benchmark of ≥80% in each year during 2012–2015. Lebanon showed substantial gaps in stool specimen adequacy before and during the outbreak with rates ranging from 45% to 70% during 2012–2014, but the rate improved to 84% in 2015.

A total of 38 WPV type 1 cases were reported during the outbreak, with dates of paralysis onset ranging from July 14, 2013 for the index case (Aleppo, Syria) to April 7, 2014 for the last confirmed case (Baghdad, Iraq). The outbreak was virologically confirmed in October 2013. Of the 38 cases reported, 36 occurred in Syria and two occurred in Iraq (Figure 1). Approximately two thirds (24 of 38) of reported cases occurred in male children and 74% of cases occurred in children aged <2 years. Fifty-eight percent of children with polio had never received oral poliovirus vaccine (OPV) either through routine or supplementary immunization (i.e., zero-dose children), and an additional 37% of children with polio had received ≤3 OPV doses. The remaining 5% of children with polio had received 3 OPV doses.

Thirty-five of the 36 polio cases in Syria were reported during 2013 and the last identified case had paralysis onset in January 2014. A breakdown of cases by governorate (Figure 2) indicates that 25 (69%) cases were reported from Deirez-Zour, five from Aleppo, three from Edleb, two from Hasakeh, and one from Hama. The two cases reported from Iraq occurred in February and April 2014; both were from Baghdad-Resafa Governorate. Both cases were related by genetic sequencing and were closely linked to WPV circulating in Syria. Genetic sequencing indicated virus circulation might have begun a year earlier somewhere in the Middle East, coincident with identification of WPV-positive environmental samples in Egypt in December 2012 (5). The implicated viral strain was genetically linked to strains circulating in Pakistan (6).

Outbreak Response Plan Development

Eight countries in the region (Egypt, Iran, Iraq, Jordan, Lebanon, Palestine, Syria, and Turkey) developed a concerted Middle East polio outbreak response plan, which was updated during the course of the outbreak. Countries were grouped into two areas: 1) countries with poliovirus transmission (Syria and Iraq), and 2) countries at significant risk for poliovirus importation based on geographic proximity and influx of displaced persons from the outbreak zone (Egypt, Iran, Jordan, Lebanon, Palestine, and Turkey). The strategic response in these areas occurred in three phases. Phase I (October 2013–April 2014) focused on interrupting WPV transmission and halting spread of the virus beyond the affected countries. Phase II (May 2014–January 2015) identified areas at high risk for poliovirus importation and circulation based on stipulated criteria, including presence of refugees and mobile populations, security-compromised areas, districts with low vaccination coverage, and geographically hard-to-reach communities. These areas were prioritized for SIAs and intensified surveillance activities. Phase III (February–October 2015) was aimed at further boosting population immunity against polio through strengthened routine immunization systems and SIAs.

Immunization Coverage. Conflict in Syria and Iraq in the years preceding and following the outbreak led to steep declines in routine vaccination coverage among children in both countries, in contrast to most other countries in the Middle East where coverage remained high. Estimated national routine vaccination coverage of infants in Syria with 3 doses of oral poliovirus vaccine (OPV3) declined from preconflict levels of 83% in 2010 to 47%–52% during 2012–2014.¶ Estimates of coverage in Iraq were ≤70% and coverage in Lebanon was 75% during 2012–2014. All other countries involved in the response had coverage levels of >90% during 2012–2014.

In response to the Middle East polio outbreak, >70 SIAs were conducted during October 2013–December 2015. SIAs targeted approximately 27 million children aged <5 years in eight countries and were conducted using trivalent (types 1, 2, and 3) and bivalent (types 1 and 3) OPV. Strategies used during the campaigns included fixed-post (health facility), house-to-house visits, transit-point vaccination, and deployment of mobile teams to vulnerable populations and geographically hard-to-reach areas. Strategies were tailored to the unique sociocultural context of each country involved in the response.

Implementation of outbreak response plan. Following identification of the outbreak, Syria conducted two rounds of national immunization days (NIDs) in November and December 2013, eight NIDs and one round of subnational immunization days (SNIDs) in 2014, and four NIDs and two SNIDs in 2015 (Table). Postcampaign monitoring coverage estimates improved from 79% in December 2013 to 93% in March 2014, with coverage levels ≥88% during a majority of the campaigns. Iraq held 14 NIDs and four SNIDs as part of the response, with postcampaign monitoring coverage levels ranging from 86% to 94% during 2014. Egypt, Iran, Jordan, Lebanon, Palestine, and Turkey conducted two to 11 vaccination campaigns.

Active conflict in many parts of Syria and some parts of Iraq limited access for vaccination activities during the course of the response. Negotiations with local authorities and engagement of community leaders enabled implementation of a limited number of vaccination campaigns in some conflict-affected areas, but it was difficult to monitor these campaigns, or generate reliable data on the quality of response activities. Egypt, Iraq, Jordan, Lebanon, and Turkey received large numbers of Syrian refugees (7), which placed significant strain on their health care resources and increased costs of implementing outbreak response activities. Refugees aged <15 years living in camps in Jordan were vaccinated against polio upon registration and entry, and during special vaccination campaigns held in camps.

In assessing the effect of outbreak response activities, the vaccination status of nonpolio AFP cases in children aged 6–59 months in Syria and Iraq was reviewed. The proportion of NPAFP cases among children aged 6–59 months who were reported to have received ≥3 doses of OPV in Syria rose from 82% in 2013 to 94% in 2015, but remained at 93% among Iraqi children of the same age group during 2013–2015. The proportion of children aged 6–59 months with NPAFP who had never received OPV, or any other form of polio vaccination, decreased from 9% in 2013 to 2% in 2015 in Syria, but increased slightly from 1% to 3% in Iraq during the same period.

Discussion

The Middle East polio outbreak occurred within an extremely challenging setting, given the ongoing civil war in Syria and conflict in several parts of Iraq. The near collapse of the health care system in conflict-affected parts of Syria resulted in plummeting levels of routine vaccination coverage that left many children born after the start of the civil war unimmunized or underimmunized against polio, and set the stage for the spread of poliovirus following importation within this age group and beyond.

Actions were taken to mitigate the risk for a polio outbreak in Syria when WPV-positive environmental isolates were identified in Egypt late in 2012. AFP surveillance activities in Syria, including in opposition-controlled areas, were intensified through WHO’s EWARN system, and polio vaccination campaigns were conducted in all of Syria’s governorates by January 2013 (6). However, the cohort of children born during the conflict remained vulnerable to a polio outbreak because of steep declines in routine polio vaccination coverage.

After a cluster of WPV cases was detected in Deirez-Zour Governorate, the government of Syria immediately declared the outbreak a public health emergency. A multicountry response plan was developed to contain and interrupt the outbreak, which was effectively contained within 6 months from the time of its identification. Improvements in AFP surveillance performance indicators in the outbreak-affected countries provided a basis for WHO to declare the outbreak over in 2015. In addition to intensified surveillance and immunization activities, the response owed its success in large part to the level of collaboration and concerted approach adopted by eight national governments in the region. Another factor contributing to the success of the response was that high routine immunization coverage in many countries in the region, coupled with high prewar vaccination coverage in Syria, limited the population of vulnerable persons to mostly children born after the onset of the civil war.

With the attention of GPEI focused on the final push to interrupt indigenous WPV transmission in the remaining three polio-endemic countries (8–10), vigilance must be maintained in the Middle East and other conflict-affected areas to forestall the risk for new WPV outbreaks. In the event of a new outbreak, the Middle East polio outbreak response provides a model for an effective response within challenging settings.

* The quality of acute flaccid paralysis (AFP) surveillance is monitored by performance indicators that include 1) the detection rate of nonpolio AFP (NPAFP) cases, and 2) the proportion of AFP cases with adequate stool specimens. World Health Organization (WHO) operational targets for countries with endemic poliovirus transmission are an NPAFP detection rate of ≥2 cases per 100,000 population aged <15 years, and adequate stool specimen collection from ≥80% of AFP cases, in which two specimens are collected ≥24 hours apart, both within 14 days of paralysis onset, and shipped on ice or frozen packs to a WHO-accredited laboratory, arriving in good condition (without leakage or desiccation).

† Mass campaigns conducted for a brief period (days to weeks) in which 1 dose of oral poliovirus vaccine is administered to all children aged <5 years, regardless of vaccination history. Campaigns are conducted nationally or subnationally (i.e., in portions of the country).

§ http://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/10665/70812/1/WHO_HSE_GAR_DCE_2012_1_eng.pdf.

¶ http://apps.who.int/immunization_monitoring/globalsummary.

References

- Akil L, Ahmad HA. The recent outbreaks and reemergence of poliovirus in war- and conflict-affected areas. Int J Infect Dis 2016;49:40–6. CrossRef PubMed

- Arie S. Polio virus spreads from Syria to Iraq. BMJ 2014;348:g2481. CrossRef PubMed

- Ahmad B, Bhattacharya S. Polio eradication in Syria. Lancet Infect Dis 2014;14:547–8. CrossRef PubMed

- Aylward B. An ancient scourge triggers a modern emergency. East Mediterr Health J 2013;19:903–4. PubMed

- World Health Organization. Outbreak news. Poliovirus isolation, Egypt. Wkly Epidemiol Rec 2013;88:74–5. PubMed

- Aylward RB, Alwan A. Polio in syria. Lancet 2014;383:489–91. CrossRef PubMed

- United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees. Syria regional refugee response: inter-agency information sharing portal. Geneva, Switzerland: United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees; 2017. http://data.unhcr.org/syrianrefugees/regional.php

- Morales M, Tangermann RH, Wassilak SG. Progress toward polio eradication—worldwide, 2015–2016. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2016;65:470–3. CrossRef PubMed

- Hampton LM, Farrell M, Ramirez-Gonzalez A, et al. ; Immunization Systems Management Group of the Global Polio Eradication Initiative. Cessation of trivalent oral poliovirus vaccine and introduction of inactivated poliovirus vaccine—worldwide 2016. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2016;65:934–8. CrossRef PubMed

- Mbaeyi C, Shukla H, Smith P, et al. Progress toward poliomyelitis eradication—Afghanistan, January 2015‒August 2016. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2016;65:1195–9. CrossRef PubMed

TABLE. Acute flaccid paralysis (AFP) surveillance indicators and outbreak response activities by country and year — eight countries in the Middle East, 2012–2015

| Year/Activity | Country | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Egypt | Iran | Iraq | Jordan | Lebanon | Palestine | Syria | Turkey | |

| 2012 | ||||||||

| Nonpolio AFP rate* | 3.9 | 3.5 | 3.8 | 1.5 | 2.2 | 1.3 | 1.4 | 0.9 |

| AFP cases with adequate specimens (%) | 92 | 92 | 90 | 84 | 50 | 95 | 84 | 80 |

| 2013 | ||||||||

| Nonpolio AFP rate* | 3 | 4 | 3.1 | 1.4 | 2.2 | 2.2 | 1.7 | 1.2 |

| AFP cases with adequate specimens (%) | 92 | 96 | 84 | 91 | 45 | 95 | 68 | 76 |

| SIAs | 2 NIDs | —† | 2 NIDs | 2 NIDs | 2 NIDs | 1 NID | 2 NIDs | 2 SNIDs |

| 1 SNID | ||||||||

| 2014 | ||||||||

| Nonpolio AFP rate* | 2.9 | 4.2 | 4 | 2.5 | 2.7 | 1.2 | 4 | 1.5 |

| AFP cases with adequate specimens (%) | 93 | 96 | 89 | 97 | 70 | 90 | 84 | 77 |

| SIAs | 2 NIDs | 2 SNIDs | 7 NIDs | 3 NIDs | 4 NIDs | 1 NID | 8 NIDs | 5 SNIDs |

| 1 SNID | 3 SNIDs | 2 SNIDs | 3 SNIDs | 1 SNID | ||||

| 2015 | ||||||||

| Nonpolio AFP rate* | 3 | 4.3 | 3.6 | 3.2 | 5.2 | 2.2 | 3 | 1.7 |

| AFP cases with adequate specimens (%) | 94 | 97 | 82 | 97 | 84 | 92 | 90 | 82 |

| SIAs | 1 NID | 2 SNIDs | 5 NIDs | 1 SNID | 2 SNIDs | —† | 4 NIDs | 2 SNIDs |

| 2 SNIDs | 2 SNIDs | |||||||

Abbreviations: NIDs = national immunization days; SIAs = supplemental immunization activities; SNIDs = subnational immunization days.

* Cases per 100,000 children aged <15 years (target: ≥2 per 100,000).

† No NIDs or SNIDs conducted for the year.

FIGURE 1. Number of cases of wild poliovirus type 1 (WPV1), by month and year of paralysis onset — Syria and Iraq, 2013–2014

FIGURE 1. Number of cases of wild poliovirus type 1 (WPV1), by month and year of paralysis onset — Syria and Iraq, 2013–2014

FIGURE 2. Cases of wild poliovirus type 1 (WPV1) — Syria and Iraq, 2013–2014*

FIGURE 2. Cases of wild poliovirus type 1 (WPV1) — Syria and Iraq, 2013–2014*

* Each dot represents one case. Dots are randomly placed within second administrative units.

Suggested citation for this article: Mbaeyi C, Ryan MJ, Smith P, et al. Response to a Large Polio Outbreak in a Setting of Conflict — Middle East, 2013–2015. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2017;66:227–231. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.15585/mmwr.mm6608a6.

The mayor of Calais has banned the distribution of food to migrants as part of a campaign to prevent the establishment of a new refugee camp

Friday, March 3rd, 2017Report of the Independent International Commission of Inquiry on the Syrian Arab Republic

Thursday, March 2nd, 2017Report of the Independent International Commission of Inquiry on the Syrian Arab Republic

The Independent International Commission of Inquiry on the Syrian Arab Republic was established on 22 August 2011 by the Human Rights Council through resolution S-17/1 adopted at its 17th special session with a mandate to investigate all alleged violations of international human rights law since March 2011 in the Syrian Arab Republic.

The Commission was also tasked to establish the facts and circumstances that may amount to such violations and of the crimes perpetrated and, where possible, to identify those responsible with a view of ensuring that perpetrators of violations, including those that may constitute crimes against humanity, are held accountable.

Aleppo aerial campaign deliberately targeted hospitals and humanitarian convoy amounting to war crimes, while armed groups’ indiscriminate shelling terrorised civilians – UN Commission

Independent International Commission of Inquiry on the Syrian Arab Republic

GENEVA (1 March 2017) – The brutal tactics used by the parties to the conflict in Syria as they engaged in the decisive battle for Aleppo city between July and December 2016 resulted in unparalleled suffering for Syrian men, women and children and amount to war crimes, according to a UN report released today.

In their report based on 291 interviews, including with residents of Aleppo city, and the review of satellite imagery, photographs, videos and medical records, the Independent International Commission of Inquiry on the Syrian Arab Republic documents daily Syrian and Russian airstrikes against eastern Aleppo over several months which steadily destroyed vital civilian infrastructure resulting in disastrous consequences for the civilian population.

By using brutal siege tactics reminiscent of medieval warfare to force surrender, Government forces and their allies prevented the civilian population of eastern Aleppo city from accessing food and basic supplies while relentless airstrikes pounded the city for months, deliberately targeting hospitals and clinics, killing and maiming civilians, and reducing eastern Aleppo to rubble, the report states.

By late November 2016 when pro-Government forces on the ground took control over eastern Aleppo, no functioning hospitals or other medical facilities remained. The intentional targeting of these medical facilities amounts to war crimes, the Commission concludes.

In the report, mandated by the Human Rights Council at its 25th special session in October 2016, the three-person Commission also notes how armed groups indiscriminately shelled civilian-inhabited areas of western Aleppo city with improvised weapons, causing many civilian casualties. A number of these attacks were carried out without a clear military target and had no other purpose than to terrorise the civilian population.

“The violence in Aleppo documented in our report should focus the international community on the continued, cynical disregard for the laws of war by the warring parties in Syria. The deliberate targeting of civilians has resulted in the immense loss of human life, including hundreds of children”, said Commission Chair Paulo Pinheiro.

In one of the most horrific attacks investigated by the Commission, Syrian Air Force deliberately targeted a United Nations/Syrian Arab Red Crescent humanitarian convoy in Orum al-Kubra, Aleppo countryside. The attack killed 14 aid workers, destroyed 17 trucks carrying aid supplies, and led to the suspension of all humanitarian aid in the Syrian Arab Republic, further aggravating the unspeakable suffering of Syrian civilians.

“Under no circumstances can humanitarian aid workers be targeted. A deliberate attack against them such as the one that took place in Orum al-Kubra amounts to war crimes and those responsible must be held accountable for their actions”, said Commissioner Carla del Ponte.

The repeated bombardments, which also destroyed schools, orphanages, markets, and residential homes, effectively made civilian life impossible and precipitated surrender. The report further stresses that Syrian aircraft used chlorine – a chemical agent prohibited under international law – against the civilian population of eastern Aleppo, causing significant physical and psychological harm to hundreds of civilians.

As it became clear that eastern Aleppo would be taken by pro-Government forces, all parties continued to commit brutal and widespread violations, the report states. In some districts, armed groups shot at civilians to prevent them from leaving, effectively using them as human shields. Pro-government forces on the ground, composed mostly of Syrian and foreign militias, executed hors de combat fighters and perceived opposition supporters, including family members of fighters. Others were arrested and their whereabouts remain unknown.

The report also notes that the eastern Aleppo evacuation agreement forced thousands of civilians – despite a lack of military necessity or deference to the choice of affected individuals – to move to Government-controlled western Aleppo whilst others were taken to Idlib where they are once more living under bombardments. In line with the precedents of Moadamyia and Darayya, this agreement confirms the regrettable trend whereby parties to the conflict in Syria use civilian populations as bargaining chips for political purposes.

“Some of these agreements amount to forced displacement. It is imperative that the parties refrain from similar future agreements and provide the conditions for the safe return of those who wish to go back to their homes in eastern Aleppo”, said Commissioner Karen AbuZayd.

Background

The Independent International Commission of Inquiry on the Syrian Arab Republic, which comprises Mr. Paulo Sérgio Pinheiro (Chair), Ms. Carla Del Ponte, and Ms. Karen Koning AbuZayd has been mandated by the United Nations Human Rights Council to investigate and record all violations of international law since March 2011 in the Syrian Arab Republic.

The full report and supporting documentation can be found on the Human Rights Council web page dedicated to the Independent International Commission of Inquiry on the Syrian Arab Republic: http://www.ohchr.org/EN/HRBodies/HRC/IICISyria/Pages/IndependentInternationalCommission.aspx

The report is scheduled to be presented on 14 March during an interactive dialogue at the 34th session of the Human Rights Council.

– See more at: http://www.ohchr.org/EN/NewsEvents/Pages/DisplayNews.aspx?NewsID=21256&LangID=E#sthash.l48EGFJw.dpuf

Neglected tropical diseases are finally getting the attention they deserve

Wednesday, February 15th, 2017“…Yet one of the most inspiring success stories is perhaps the one most overlooked: the global effort to eliminate neglected tropical diseases, or NTDs.

Much of the recent success stems from a meeting in London on Jan. 30, 2012 ……

NTDs affect nearly 1.5 billion of the poorest and most marginalized people around the world. And while 500,000 people lose their lives to NTDs every year, these diseases are more likely to disable and disfigure than to kill. …….These agonizing conditions keep children from school and adults from work, trapping families and communities in cycles of poverty……

Today, the landscape is dramatically different. In 2015, nearly 1 billion people received NTD treatments — 20 percent more than just two years before. As a result, fewer people are suffering from these diseases than at any point in history. ……Much of this success can be traced to the 2012 meeting in London. There, the World Health Organization, pharmaceutical companies, donors, governments, and non-governmental organizations committed to work together to control and eliminate 10 NTDs. …”

Legatum Foundation: Allocating capital at the bottom of the Prosperity Ladder to projects, people and ideas that create sustainable prosperity.

Wednesday, February 15th, 2017War and economic crisis in Yemen has left an estimated 3.3 million people, including 2.2 million children, suffering from acute malnutrition and 460,000 under 5 have severe acute malnutrition.

Tuesday, January 31st, 2017Meritxell Relano, UNICEF representative in Yemen:

“Because of the crumbling health system, the conflict and economic crisis, we have gone back to 10 years ago. A decade has been lost in health gains,” she said, with 63 out of every 1,000 live births now dying before their fifth birthday, against 53 children in 2014.

Yemen has been divided by nearly two years of civil war that pits the Iran-allied Houthi group against a Sunni Arab coalition led by Saudi Arabia. At least 10,000 people have been killed in the fighting.

Releno later told a news briefing that the rate of severe acute malnutrition had “tripled” between 2014 and 2016 to 460,000 children…..”