Archive for the ‘Lassa Fever’ Category

WHO: After nearly 400 confirmed infections and 100 deaths, the spread of Lassa fever in Nigeria is beginning to slow but the epidemic is far from contained.

Sunday, April 1st, 201826 MARCH 2018 | ABUJA, NIGERIA – After nearly 400 confirmed infections and 100 deaths, the spread of Lassa fever in Nigeria is beginning to slow but the epidemic is far from contained, the World Health Organization and the Nigeria Centre for Disease Control (NCDC) have warned.

NCDC’s latest data shows that the number of new confirmed and probable cases has been falling for five consecutive weeks, indicating that public health measures are proving effective, but more infections are expected until the end of the dry season, as the viral haemorrhagic fever is endemic to the area.

Between 1 January and 25 March 2018, the NCDC reported 394 laboratory confirmed cases. There were 18 new confirmed cases in the last reporting week (19-25 March 2018), compared to 54 confirmed cases a month earlier (19-25 February 2018).

“We should interpret the recent declining trend in new cases with caution. The Lassa fever season is not yet over. We need to maintain vigilance and response operations, and ensure continued engagement with communities to help curb the further spread of Lassa fever,” said Dr Wondimagegnehu Alemu, WHO Representative to Nigeria.

The current epidemic is Nigeria’s largest on record, with the number of confirmed cases in January and February alone exceeding the total number reported in the whole of 2017.

The case count has not yet fallen to usual endemic levels and the exact cause for the high numbers of infections has not been pinpointed. Research is being conducted in real-time to answer some of these questions.

“We are researching what has led to so many people becoming infected with Lassa fever,” said Dr Chikwe Ihekweazu, Chief Executive Officer of the NCDC. “Even with a downward trend, until we can better understand the causes behind its rapid spread, we must treat the outbreak as a priority.”

Whole genome sequencing can reveal information that contributes to the understanding and the control of infectious disease outbreaks.

Researchers at the Irrua Specialist Teaching Hospital – in collaboration with the Bernhard-Nocht Institute for Tropical Medicine, Germany, WHO, NCDC and others – have conducted genome sequencing of the Lassa virus.

The preliminary results suggest that the circulating virus is consistent with previous outbreaks and not caused by a new more virulent strain.

“By conducting research as the Lassa fever outbreak unfolds, Nigeria is a pioneering a new approach. Until now research in Africa has taken place much later in the response cycle. This is a new approach which opens the way to much more effective control of emerging and dangerous pathogens,” said Dr Alemu.

WHO recognizes Lassa fever as a priority pathogen which has the potential to cause a public health emergency. The ongoing research will provide crucial insights which will help mitigate future Lassa fever outbreaks.

WHO has been working with NCDC and other partners to control Lassa fever by deploying teams to hotspots, identifying and treating patients, strengthening infection, prevention and control measures in health facilities, and engaging with communities.

WHO has released US$900,000 from its Contingency Fund for Emergencies to quickly scale up operations, and is also supporting preparedness and response capacities in neighbouring countries.

Nigeria: the government of the Ebonyi state urged people in rural areas, where rat consumption is common, to refrain from eating rat meat in an effort to curb Lassa transmission.

Wednesday, March 21st, 2018Disease X: A pathogen with the potential to spread and kill millions but for which there are currently no, or insufficient, countermeasures available.

Sunday, March 11th, 2018“……It was the third time the committee, consisting of leading virologists, bacteriologists and infectious disease experts, had met to consider diseases with epidemic or pandemic potential. But when the 2018 list was released two weeks ago it included an entry not seen in previous years.

- Crimean-Congo haemorrhagic fever (CCHF)

- Ebola virus disease and Marburg virus disease

- Lassa fever

- Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus (MERS-CoV) and Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome (SARS)

- Nipah and henipaviral diseases

- Rift Valley fever (RVF)

- Zika

- Disease X

*Diseases posing significant risk of an international public health emergency for which there is no, or insufficient, countermeasures. Source: World Health Organization (WHO), 2018

The Nigerian Lassa fever outbreak continues to grow, with more than 1,000 suspected cases

Wednesday, March 7th, 2018Nigeria Centre for Disease Control

HIGHLIGHTS

In the reporting Week 09 (February 26-March 4,2018) thirty five new confirmed cases were recorded from five States Edo (19), Ondo (5), Bauchi (1), Ebonyi (9), and Plateau (1), with seven new deaths in confirmed cases from three states Ondo (2), Edo (2), and Ebonyi (3)

From 1st January to 4th March 2018, a total of 1121 suspected cases. Of these, 353 are confirmed positive, 8 are probable, 723 are negative (not a case) and 37 are awaiting laboratory results (pending).

18 States are active (Edo, Ondo, Bauchi, Nasarawa, Ebonyi, Anambra, Benue, Kogi, Imo, Plateau, Lagos, Taraba, Delta, Osun, Rivers, FCT, Gombe and Ekiti)

Since the onset of the 2018 outbreak, there have been 110 deaths: 78 in positive-confirmed cases, 8 in probable cases and 24 in negative cases.

Case Fatality Rate in confirmed and probable cases is 23.8%

Two health workers were confirmed positive this week in Ebony State. Cumulatively, sixteen health care workers have been affected in six states –Ebonyi (9), Nasarawa (1), Kogi (1), Benue (1), Ondo (1) and Edo (3) with four deaths in Ebonyi (3) and Kogi

Predominant age-group affected is 21-40 years (Range: 9 months to 92 years, Median Age: 34 years)

The male to female ratio for confirmed cases is 2:1

85% of all confirmed cases are from Edo (44%) Ondo (25%) and Ebony(16%)states

Cases currently on admission this weekend at Irrua Specialist Hospital (35), FMC Owo (18) and FETH Abakiliki (16) all isolation beds at the treatment facilities occupied.

National RRT team (NCDC staff and NFELTP residents) batch B continues response support in Ebonyi, Ondo and Edo States

A total of 3126 contacts have been identified from 18 active states. Of these 1586 are currently being followed up, 1485 have completed 21 days follow up and 21 of the 47 symptomatic contacts have tested positive from 3 states (Edo-11, Ondo-7 and Ebonyi-3)

WHO and NCDC has scaled up response at National and State levels Bernhard Nocht Institute for Tropical Medicine Germany is currently supporting ISTH, NRL and LUTH Laboratories with testing reagents NCDC distributed response commodities -PPEs, Ribavirin (injection and tablets), beds, body bags and hand sanitizers to FMC Owo, FETH Abakiliki, Niger and Ekiti states in the reporting week NCDC is collaborating with ALIMA and MSF in Edo, Ondo and Anambra States to support case management NCDC deployed teams to four Benin Republic border states (Kebbi, Kwara, Niger and Oyo) for enhanced surveillance activities National Lassa fever multi-partner multi-agency Emergency Operations Centre (EOC) continues to coordinate the response activities at all levels

The World Health Organization is scaling up its response to an outbreak of Lassa fever in Nigeria, which has spread to 17 states and may have infected up to 450 people in less than five weeks.

Wednesday, February 14th, 2018“13 February 2018, ABUJA – The World Health Organization is scaling up its response to an outbreak of Lassa fever in Nigeria, which has spread to 17 states and may have infected up to 450 people in less than five weeks.

From the onset of the outbreak, WHO Nigeria deployed staff from the national and state levels to support the Government of Nigeria’s national Lassa fever Emergency Operations Centre and state surveillance activities. WHO is helping to coordinate health actors and is joining rapid risk assessment teams travelling to hot spots to investigate the outbreak.

Between 1 January and 4 February 2018, nearly 450 suspected cases were reported, of which 132 are laboratory confirmed Lassa fever. Of these, 43 deaths were reported, 37 of which were lab confirmed.

The acute viral haemorrhagic fever is endemic in Nigeria but for the current outbreak the hot spots are the southern states of Edo, Ondo and Ebonyi.

“The high number of Lassa fever cases is concerning. We are observing an unusually high number of cases for this time of year.” said Dr. Wondimagegnehu Alemu, WHO Representative to Nigeria.

Among those infected are 11 health workers, four of whom have died. WHO is advising national authorities on strengthening infection, prevention and control practices in healthcare settings. Healthcare workers caring for Lassa fever patients require extra infection and control measures, including the use of personal protective equipment to prevent contact with patients’ bodily fluids.

With the increase in the number of cases, WHO initially donated personal protective equipment to the Nigeria Center for Disease Control and to the affected states and procured laboratory reagents to support the prompt diagnosis of Lassa fever. WHO is deploying international experts to coordinate the response, strengthen surveillance, provide treatment guidelines, and engage with communities to raise awareness on prevention and treatment.

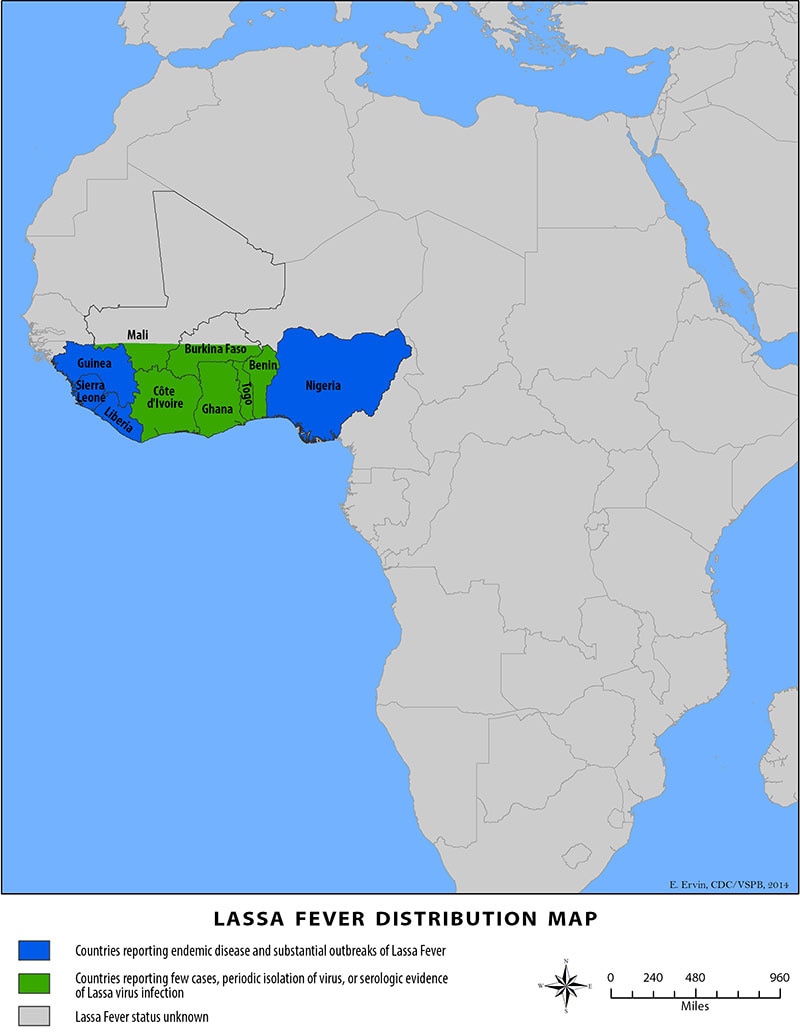

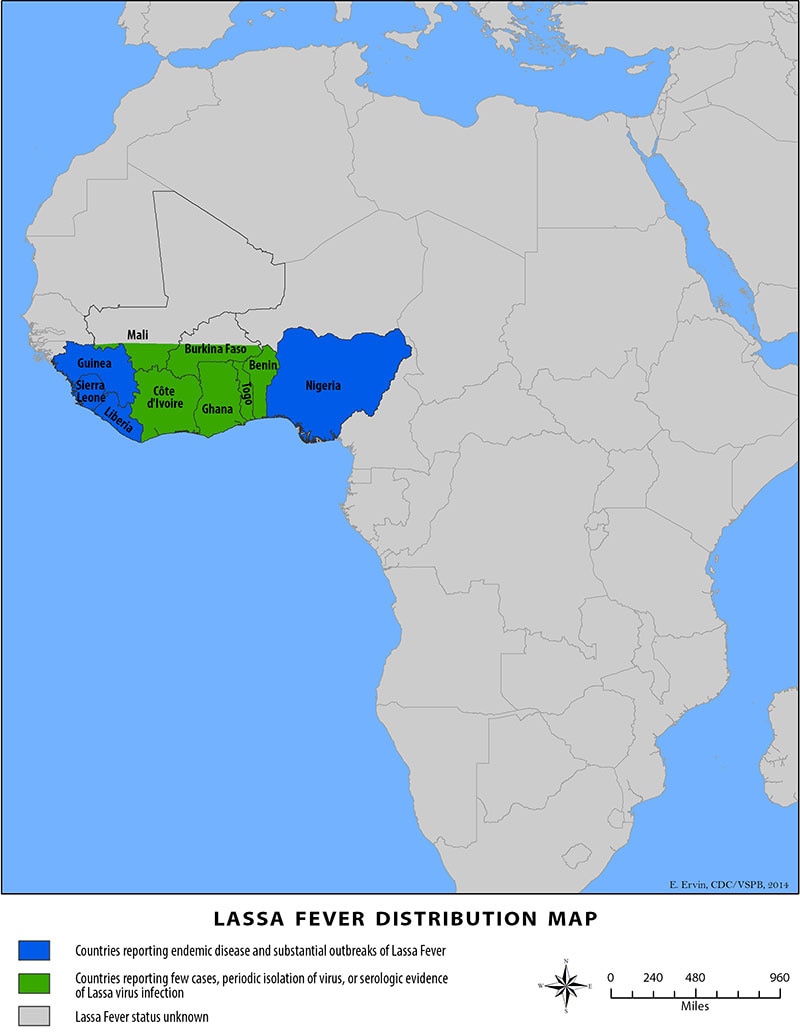

Lassa fever is endemic to several West African countries. Benin, Liberia and Sierra Leone have all reported cases in the past month. WHO is working with countries in the region to strengthen coordination and cross-border cooperation.”

Lassa Fever: Nigeria has activated its emergency operations center to coordinate the outbreak response

Saturday, January 27th, 2018The Nigeria Centre for Disease Control (NCDC) was established in the year 2011 in response to the challenges of public health emergencies and to enhance Nigeria’s preparedness and response to epidemics through prevention, detection and control of communicable and non-communicable diseases.

“…..Since the beginning of 2018, a total number of 107 suspected Lassa fever cases have been recorded in ten States: Edo, Ondo, Bauchi, Nasarawa, Ebonyi, Anambra, Benue, Kogi, Imo and Lagos States. As at 21st January 2018, the total number of confirmed cases is 61, with 16 deaths recorded. Ten health care workers have been infected in four States (Ebonyi – 7, Nasarawa – 1, Kogi – 1 and Benue – 1) with three deaths in Ebonyi State. ….”

Lassa Fever Case Report: Combination therapy with intravenous ribavirin and oral favipiravir

Saturday, July 1st, 2017Favipiravir and Ribavirin Treatment of Epidemiologically Linked Cases of Lassa Fever

Lassa fever: WHO Review

Tuesday, April 4th, 2017Lassa fever

Key facts

- Lassa fever is an acute viral haemorrhagic illness of 2-21 days duration that occurs in West Africa.

- The Lassa virus is transmitted to humans via contact with food or household items contaminated with rodent urine or faeces.

- Person-to-person infections and laboratory transmission can also occur, particularly in hospitals lacking adequate infection prevent and control measures.

- Lassa fever is known to be endemic in Benin, Ghana, Guinea, Liberia, Mali, Sierra Leone, and Nigeria, but probably exists in other West African countries as well.

- The overall case-fatality rate is 1%. Observed case-fatality rate among patients hospitalized with severe cases of Lassa fever is 15%.

- Early supportive care with rehydration and symptomatic treatment improves survival.

Background

Though first described in the 1950s, the virus causing Lassa disease was not identified until 1969. The virus is a single-stranded RNA virus belonging to the virus family Arenaviridae.

About 80% of people who become infected with Lassa virus have no symptoms. 1 in 5 infections result in severe disease, where the virus affects several organs such as the liver, spleen and kidneys.

Lassa fever is a zoonotic disease, meaning that humans become infected from contact with infected animals. The animal reservoir, or host, of Lassa virus is a rodent of the genus Mastomys, commonly known as the “multimammate rat.” Mastomys rats infected with Lassa virus do not become ill, but they can shed the virus in their urine and faeces.

Because the clinical course of the disease is so variable, detection of the disease in affected patients has been difficult. When presence of the disease is confirmed in a community, however, prompt isolation of affected patients, good infection prevention and control practices, and rigorous contact tracing can stop outbreaks.

Lassa fever is known to be endemic in Benin (where it was diagnosed for the first time in November 2014), Ghana (diagnosed for the first time in October 2011), Guinea, Liberia, Mali (diagnosed for the first time in February 2009), Sierra Leone, and Nigeria, but probably exists in other West African countries as well.

Symptoms of Lassa fever

The incubation period of Lassa fever ranges from 6–21 days. The onset of the disease, when it is symptomatic, is usually gradual, starting with fever, general weakness, and malaise. After a few days, headache, sore throat, muscle pain, chest pain, nausea, vomiting, diarrhoea, cough, and abdominal pain may follow. In severe cases facial swelling, fluid in the lung cavity, bleeding from the mouth, nose, vagina or gastrointestinal tract and low blood pressure may develop.

Protein may be noted in the urine. Shock, seizures, tremor, disorientation, and coma may be seen in the later stages. Deafness occurs in 25% of patients who survive the disease. In half of these cases, hearing returns partially after 1–3 months. Transient hair loss and gait disturbance may occur during recovery.

Death usually occurs within 14 days of onset in fatal cases. The disease is especially severe late in pregnancy, with maternal death and/or fetal loss occurring in more than 80% of cases during the third trimester.

Transmission

Humans usually become infected with Lassa virus from exposure to urine or faeces of infected Mastomys rats. Lassa virus may also be spread between humans through direct contact with the blood, urine, faeces, or other bodily secretions of a person infected with Lassa fever. There is no epidemiological evidence supporting airborne spread between humans. Person-to-person transmission occurs in both community and health-care settings, where the virus may be spread by contaminated medical equipment, such as re-used needles. Sexual transmission of Lassa virus has been reported.

Lassa fever occurs in all age groups and both sexes. Persons at greatest risk are those living in rural areas where Mastomys are usually found, especially in communities with poor sanitation or crowded living conditions. Health workers are at risk if caring for Lassa fever patients in the absence of proper barrier nursing and infection prevention and control practices.

Diagnosis

Because the symptoms of Lassa fever are so varied and non-specific, clinical diagnosis is often difficult, especially early in the course of the disease. Lassa fever is difficult to distinguish from other viral haemorrhagic fevers such as Ebola virus disease as well as other diseases that cause fever, including malaria, shigellosis, typhoid fever and yellow fever.

Definitive diagnosis requires testing that is available only in reference laboratories. Laboratory specimens may be hazardous and must be handled with extreme care. Lassa virus infections can only be diagnosed definitively in the laboratory using the following tests:

- reverse transcriptase polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) assay

- antibody enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA)

- antigen detection tests

- virus isolation by cell culture.

Treatment and prophylaxis

The antiviral drug ribavirin seems to be an effective treatment for Lassa fever if given early on in the course of clinical illness. There is no evidence to support the role of ribavirin as post-exposure prophylactic treatment for Lassa fever.

There is currently no vaccine that protects against Lassa fever.

Prevention and control

Prevention of Lassa fever relies on promoting good “community hygiene” to discourage rodents from entering homes. Effective measures include storing grain and other foodstuffs in rodent-proof containers, disposing of garbage far from the home, maintaining clean households and keeping cats. Because Mastomys are so abundant in endemic areas, it is not possible to completely eliminate them from the environment. Family members should always be careful to avoid contact with blood and body fluids while caring for sick persons.

In health-care settings, staff should always apply standard infection prevention and control precautions when caring for patients, regardless of their presumed diagnosis. These include basic hand hygiene, respiratory hygiene, use of personal protective equipment (to block splashes or other contact with infected materials), safe injection practices and safe burial practices.

Health-care workers caring for patients with suspected or confirmed Lassa fever should apply extra infection control measures to prevent contact with the patient’s blood and body fluids and contaminated surfaces or materials such as clothing and bedding. When in close contact (within 1 metre) of patients with Lassa fever, health-care workers should wear face protection (a face shield or a medical mask and goggles), a clean, non-sterile long-sleeved gown, and gloves (sterile gloves for some procedures).

Laboratory workers are also at risk. Samples taken from humans and animals for investigation of Lassa virus infection should be handled by trained staff and processed in suitably equipped laboratories under maximum biological containment conditions.

On rare occasions, travellers from areas where Lassa fever is endemic export the disease to other countries. Although malaria, typhoid fever, and many other tropical infections are much more common, the diagnosis of Lassa fever should be considered in febrile patients returning from West Africa, especially if they have had exposures in rural areas or hospitals in countries where Lassa fever is known to be endemic. Health-care workers seeing a patient suspected to have Lassa fever should immediately contact local and national experts for advice and to arrange for laboratory testing.

WHO response

The Ministries of Health of Guinea, Liberia and Sierra Leone, WHO, the Office of United States Foreign Disaster Assistance, the United Nations, and other partners have worked together to establish the Mano River Union Lassa Fever Network. The programme supports these 3 countries in developing national prevention strategies and enhancing laboratory diagnostics for Lassa fever and other dangerous diseases. Training in laboratory diagnosis, clinical management, and environmental control is also included.

WHO: 3 African nations—Benin, Togo, and Burkina Faso—have reported recent cases of Lassa fever that could foretell more outbreaks in the region.

Sunday, March 12th, 2017Lassa Fever – Benin, Togo and Burkina Faso

Benin and Togo, exported from Benin

On 20 February 2017, the Ministry of Health of Benin notified WHO of a Lassa fever case in Tchaourou district, Borgou Department, Benin, close to the border with Nigeria. The case was a pregnant woman who was living in Nigeria (close to the border with Benin).

On 11 February 2017, she was admitted to a hospital where she delivered the baby (a premature neonate) by caesarean section and passed away on 12 February 2017. Samples were tested positive for Lassa fever in the laboratory in Cotonou, Benin and later in the Lagos University Teaching Hospital Lassa laboratory in Nigeria. The newborn and father left the hospital without notice on 14 February 2017 and went to Mango in northern Togo where they were admitted to a hospital.

The newborn tested positive for Lassa fever and the father tested negative in the Institut National d’Hygiène in Lomé, Togo. The baby was treated with ribavirin and is currently in stable condition; he is still hospitalised in northern Togo for issues of prematurity and overall monitoring.

A total of 68 contacts are being followed-up in Benin and 29 contacts are being followed-up in Togo linked to the pregnant woman and newborn.

Togo, exported from Burkina Faso

On 26 February 2017, after receiving information from Togo, the Ministry of Health of Burkina Faso has notified WHO of a confirmed Lassa fever case in a hospital in the northern part of Togo. The case has originated from Ouargaye district which is in the central eastern part of Burkina Faso.

The case was a pregnant woman who was previously hospitalized in Burkina Faso. She was discharged and had a miscarriage at home. After the second hospitalization in Burkina Faso she was transmitted to a hospital in Mango, northern Togo, and passed away on 3 March 2017.

Samples from the pregnant woman tested positive for Lassa fever at the Institut National d’Hygiène in Lomé, Togo.

A total of 7 contacts have been identified in Togo linked to the pregnant woman and contact tracing is ongoing; 135 contacts in Burkina Faso have been identified linked to the pregnant woman and contact tracing is ongoing.

Togo

On 2 March 2017, a man was admitted to a health centre in the Kpendial health district for fever and melena and was referred to a regional hospital on 3 March 2017.

Samples from the male case were sent to the Institut National d’Hygiène in Lomé, Togo, and tested positive for Lassa fever. The case left the hospital on 6 March. Investigations are ongoing. The male case and his close relatives are under follow up at their home.

A total of 18 contacts were identified in Togo linked to the male case.

Public health response

Health authorities in Benin, Burkina Faso and Togo are implementing the following measures to respond to these Lassa fever cases, including:

- Deployment of rapid response teams to the affected areas for epidemiological investigation.

- Identification of contacts and follow-up.

- Strengthening of infection prevention and control measures in health facilities and briefing of health workers.

- Strengthening of cross border collaboration and information exchanges between Togo, Burkina, Mali and Benin.

WHO risk assessment

Lassa fever is an acute viral haemorrhagic fever illness. The Lassa virus is transmitted to humans via contact with food or household items contaminated with rodent urine or faeces. Person-to-person infections and laboratory transmission can also occur.

Lassa fever is endemic in neighbouring Nigeria and other West African countries and causes outbreaks almost every year in different parts of the region, with yearly peaks observed between December and February. The most recent Lassa fever outbreak in Benin occurred in the same area in January – May 2016. At least 54 cases including 28 deaths have been reported at country level. Both Burkina Faso and Togo have reported sporadic cases in the past.

Given constant important population movements between Nigeria, Togo, Burkina Faso, Niger and Benin, the occurrence of sporadic Lassa fever cases in West Africa was expected and further sporadic cases may occur in countries of the region.

However, with the ongoing control measures in Benin, Togo and Burkina Faso the risk of further disease spread from these confirmed cases is considered to be low. Considering the seasonal peaks in previous years, increase in the disease awareness, better preparedness and response in general, and strengthening of regional collaboration the risk of large scale outbreaks in the region is medium.

WHO advice

Prevention of Lassa fever relies on promoting good “community hygiene” to discourage rodents from entering homes. In health-care settings, staff should always apply standard infection prevention and control precautions when caring for patients, regardless of their presumed diagnosis.

On rare occasions, travellers from areas where Lassa fever is endemic export the disease to other countries. Although other tropical infections are much more common, the diagnosis of Lassa fever should be considered in febrile patients returning from West Africa, especially if they have had exposures in rural areas or hospitals in countries where Lassa fever is known to be endemic. Health-care workers seeing a patient suspected to have Lassa fever should immediately contact local and national experts for advice and to arrange for laboratory testing.

WHO has been notified of at least 38 suspected cases of Lassa fever in Liberia.so far this year

Saturday, May 21st, 2016Lassa Fever – Liberia

Since 1 January 2016, WHO has been notified of at least 38 suspected cases of Lassa fever in Liberia.

Suspected cases were reported from 6 prefectures: Bong (17 cases, including 9 deaths), Nimba (14 cases, including 6 deaths), Gbarpolu (4 cases), Lofa (1 case), Margibi (1 case) and Montserrado (1 case).

Between 1 January and 3 April 2016, samples from 24 suspected cases were received for laboratory testing. Of these 24 suspected cases, 7 are reported to have tested positive for Lassa fever:

- 2 cases were identified by polymerase chain reaction (PCR);

- 2 cases were identified through the detection of IgM antibodies using enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA);

- 2 cases were identified through the detection of Lassa virus antigens using ELISA;

- information on the type of testing employed to identify the seventh case is not currently available.

All the Lassa fever confirmed cases tested negative for Ebola virus disease. Since there are no designated laboratories in Liberia that can test samples for Lassa fever by PCR, specimens are currently sent for testing to Kenema, Sierra Leone.

Public health response

To date, 134 contacts have completed the 21-day follow-up period. A total of 17 additional contacts are being monitored. None of these contacts have so far developed symptoms.

Appropriate outbreak response measures, including case management, infection prevention and control, community engagement and health education, have been put in place by the national authorities with the support of WHO and partner organizations.

WHO risk assessment

Lassa fever is endemic in Liberia and causes outbreaks almost every year in different parts of the country. Based on experiences from previous similar events, it is expected that additional cases will be reported.

Although occasional travel-associated cases of Lassa fever have been reported in the past (see DON published on 27 and 8 April 2016), the risk of disease spread from Liberia to non-endemic countries is considered to be low. WHO continues to monitor the epidemiological situation and conduct risk assessments based on the latest available information.

WHO advice

Considering the seasonal flare ups of cases during this time of the year, countries in West Africa that are endemic for Lassa fever are encouraged to strengthen their related surveillance systems.

Health-care workers caring for patients with suspected or confirmed Lassa fever should apply extra infection control measures to prevent contact with the patient’s blood and body fluids and contaminated surfaces or materials such as clothing and bedding. When in close contact (within 1 metre) of patients with Lassa fever, health-care workers should wear face protection (a face shield or a medical mask and goggles), a clean, non-sterile long-sleeved gown, and gloves (sterile gloves for some procedures).

Laboratory workers are also at risk. Samples taken from humans and animals for investigation of Lassa virus infection should be handled by trained staff and processed in suitably equipped laboratories under maximum biological containment conditions.

The diagnosis of Lassa fever should be considered in febrile patients returning from areas where Lassa fever is endemic. Health-care workers seeing a patient suspected to have Lassa fever should immediately contact local and national experts for advice and to arrange for laboratory testing.

WHO does not recommend any travel or trade restriction to Liberia based on the current information available.

Key facts

- Lassa fever is an acute viral haemorrhagic illness of 2-21 days duration that occurs in West Africa.

- The Lassa virus is transmitted to humans via contact with food or household items contaminated with rodent urine or faeces.

- Person-to-person infections and laboratory transmission can also occur, particularly in hospitals lacking adequate infection prevent and control measures.

- Lassa fever is known to be endemic in Benin, Ghana, Guinea, Liberia, Mali, Sierra Leone, and Nigeria, but probably exists in other West African countries as well.

- The overall case-fatality rate is 1%. Observed case-fatality rate among patients hospitalized with severe cases of Lassa fever is 15%.

- Early supportive care with rehydration and symptomatic treatment improves survival.

Symptoms of Lassa fever

The incubation period of Lassa fever ranges from 6–21 days.

The onset of the disease, when it is symptomatic, is usually gradual, starting with fever, general weakness, and malaise.

After a few days, headache, sore throat, muscle pain, chest pain, nausea, vomiting, diarrhoea, cough, and abdominal pain may follow.

In severe cases facial swelling, fluid in the lung cavity, bleeding from the mouth, nose, vagina or gastrointestinal tract and low blood pressure may develop.