Archive for the ‘Malaria’ Category

New research: Cytotoxic lymphocytes (CTLs) and cerbral malaria

Tuesday, February 18th, 2020Researchers at the National Institutes of Health found evidence that specific immune cells may play a key role in the devastating effects of cerebral malaria, a severe form of malaria that mainly affects young children. The results, published in the Journal of Clinical Investigation, suggest that drugs targeting T cells may be effective in treating the disease. The study was supported by the NIH Intramural Research Program.

Specific immune cells accumulate within brain blood vessels of people affected by cerebral malaria. This finding suggests a new treatment strategy for the disease. McGavern Lab/NINDS

Specific immune cells accumulate within brain blood vessels of people affected by cerebral malaria. This finding suggests a new treatment strategy for the disease. McGavern Lab/NINDS

“This is the first study showing that T cells target blood vessels in brains of children with cerebral malaria,” said Dorian McGavern, Ph.D., chief of the Viral Immunology and Intravital Imaging Section at the NIH’s National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke (NINDS) who co-directed the study with Susan Pierce, Ph.D., chief of the Laboratory of Immunogenetics at the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (NIAID). “These findings build a bridge between mouse and human cerebral malaria studies by implicating T cells in the development of disease pathology in children. It is well established that T cells cause the brain vasculature injury associated with cerebral malaria in mice, but this was not known in humans.”

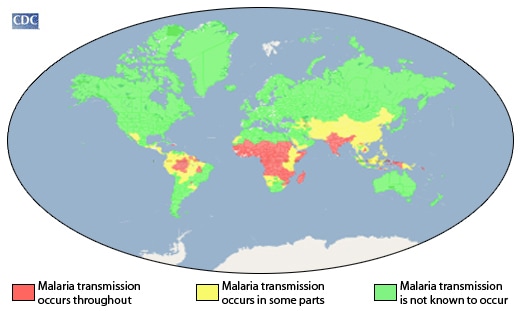

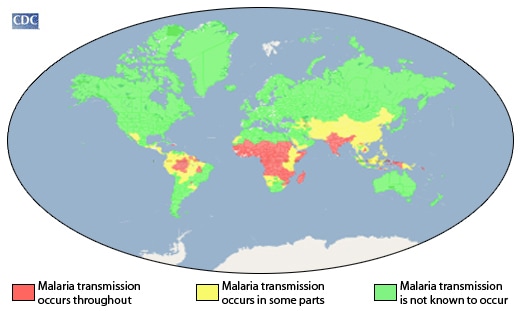

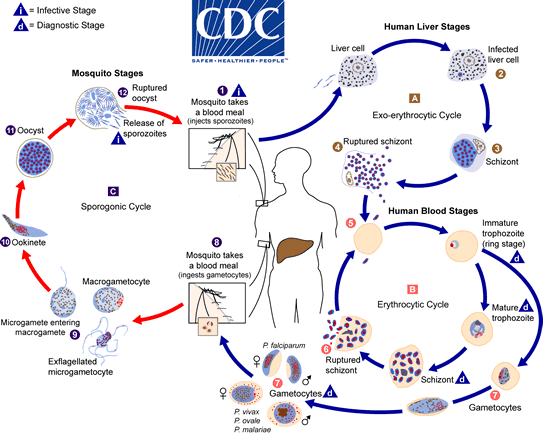

More than 200 million people worldwide are infected annually with mosquito-borne parasites that cause malaria. In a subset of those patients, mainly young children, the parasites accumulate in brain blood vessels causing cerebral malaria, which leads to increased brain pressure from swelling. Even with available treatment, cerebral malaria still kills up to 25% of those affected resulting in nearly 400,000 deaths annually. Children who survive the infection will often have long-lasting neurological problems such as cognitive impairment.

The researchers, led by Drs. Pierce and McGavern, examined brain tissue from 23 children who died of cerebral malaria and 11 children who died from other causes. The scientists used state-of-the-art microscopy to explore the presence of cytotoxic lymphocytes (CTLs) in the brain tissue samples. CTLs are a type of T cell in our immune system that is responsible for controlling infections throughout the body.

Current treatment strategies for cerebral malaria focus on red blood cells, which are thought to clog blood vessels and create potentially fatal blockages leading to extreme pressure in the brain. However, findings in the mouse model demonstrated that CTLs damage blood vessels, leading to brain swelling and death. The role of CTLs in cerebral malaria in children hasn’t been thoroughly investigated prior to this study.

The results of the current study demonstrate an increased accumulation of CTLs along the walls of brain blood vessel in the cerebral malaria tissue samples compared to non-cerebral malaria cases. In addition, the CTLs were shown to contain and release effector molecules, which damage cells, suggesting that CTLs play a critical role in cerebral malaria by damaging the walls of brain blood vessels.

“The disease appears to be an immunological accident in which the CTLs are trying to control a parasitic infection but end up injuring brain blood vessels in the process,” said Dr. McGavern.

“In separate studies we discovered that treatment of mice with a drug that targets T cells rescued over 60% of otherwise fatal cases of experimental cerebral malaria,” said Dr. Pierce. “Given our findings of T cells in the brain vasculature of children who died of the disease, we are excited by the possibility that this drug may be the first therapy for cerebral malaria.”

The impact of HIV coinfection on the risk of developing cerebral malaria is not known. The NIH researchers compared CTL patterns in the cerebral malaria cases that were co-infected with HIV and those that were HIV negative. In the HIV-negative cases, the CTLs were seen lining up against the inside wall of brain blood vessels. In the HIV-positive cases, the CTLs had migrated across the surface to the outside of the vessels. There were also significantly more CTLs present in the HIV-positive cases.

Together these findings suggest that CTLs may play an important role in cerebral malaria and that HIV infection may worsen the disease.

Additional research is needed to uncover the role of T cells in human cerebral malaria. Future studies will also investigate how targeting T cells may help treat the disease. Plans for a clinical trial are underway to test the effects of a specific T cell blocker in cerebral malaria patients in Malawi.

The NINDS is the nation’s leading funder of research on the brain and nervous system. The mission of NINDS is to seek fundamental knowledge about the brain and nervous system and to use that knowledge to reduce the burden of neurological disease.

NIAID conducts and supports research — at NIH, throughout the United States, and worldwide — to study the causes of infectious and immune-mediated diseases, and to develop better means of preventing, diagnosing and treating these illnesses. News releases, fact sheets and other NIAID-related materials are available on the NIAID website.

PAHO: Epidemiological Update: Malaria in the Americas

Thursday, November 21st, 2019Pan American Health Organization / World Health Organization. Epidemiological Update:

Malaria in the Americas. 18 November 2019, Washington, D.C.: PAHO/WHO; 2019

“Between 2005 and 2014, there was an overall decreasing trend in the number of cases of malaria in the Region of the Americas; however, since 2015, there has been an increase in the number of malaria cases reported in the Region. This overall increase is due to the increase in cases over the last three years in the Bolivarian Republic of Venezuela along with increased transmission in endemic areas of countries such as Brazil, Colombia, Guyana, Nicaragua, and Panama, as well as outbreaks in countries that were moving towards elimination (Costa Rica, the Dominican Republic, and Ecuador)…..”

Welcome to the Insecticide-Treated Net (ITN) Access and Use Report.

Tuesday, September 24th, 2019JohnsHopkins

“……The Johns Hopkins Center for Communication Programs is launching a user-friendly, interactive website that pulls together the latest data on trends in the use of insecticide-treated nets in sub-Saharan Africa and Asia to prevent malaria……”

A Case of Malaria: A 37-year-old woman from Denmark with no underlying conditions and no previous history of malaria traveled with her husband and children for 6 weeks in various parts of peninsular Malaysia and Thailand in 2018. None of them took malaria chemoprophylaxis; however, they used mosquito repellents and mosquito nets.

Monday, September 23rd, 2019Hartmeyer GN, Stensvold CR, Fabricius T, Marmolin ES, Hoegh SV, Nielsen HV, et al. Plasmodium cynomolgi as Cause of Malaria in Tourist to Southeast Asia, 2018. Emerg Infect Dis. 2019;25(10):1936-1939. https://dx.doi.org/10.3201/eid2510.190448

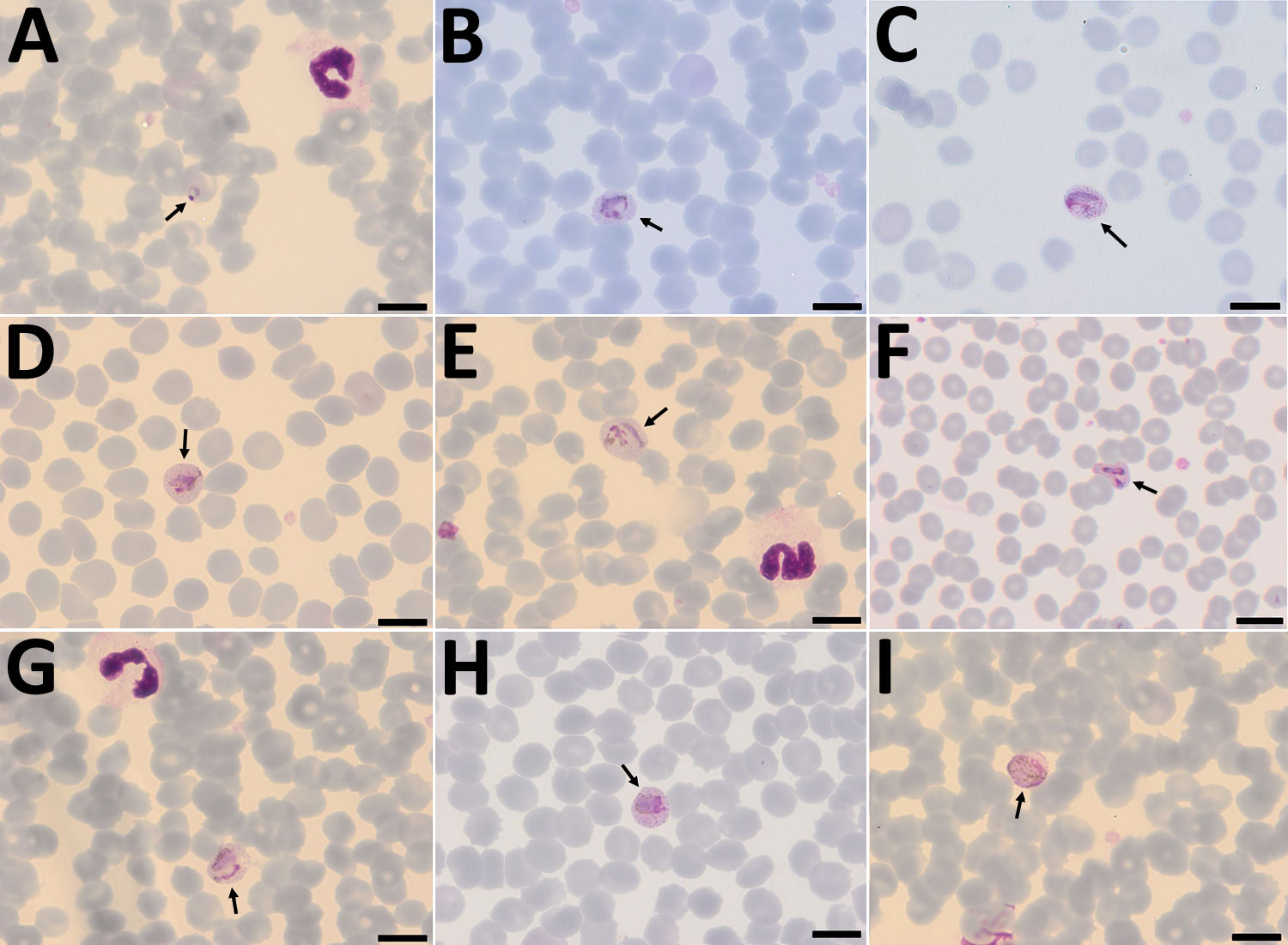

Figure 1. Plasmodium cynomolgi parasites (arrows) in Giemsa-stained thin smears of blood from a traveler returning from Southeast Asia to Denmark. Overall, few parasites were visible in the thin film, and no schizonts were visible at all. A) Young trophozoite. The cytoplasm is ring shaped, and the nucleus is spherical. The erythrocyte is not enlarged, and neither Schüffner’s dots nor pigment are visible. B) Growing trophozoite. The young parasite is ring shaped and takes up more than half of the diameter of the host erythrocyte. The cytoplasm has become slightly amoeboid. Schüffner’s dots are more prominent than in P. vivax at this stage. Pigment is visible as small yellowish granules in the cytoplasm. Erythrocyte enlargement is not evident. C) Growing trophozoite. The cytoplasm appears amoeboid but relatively compact. Schüffner’s dots are prominent, but no pigment is seen in the cytoplasm. The erythrocyte is slightly enlarged. D) Growing trophozoite. The cytoplasm appears amoeboid, and the nucleus has increased in size. Schüffner’s dots and yellowish pigment are prominent. Enlargement of the erythrocyte is evident. E) Growing trophozoite. The host cell is further enlarged. The cytoplasm is amoeboid as in P. vivax at this stage. Schüffner’s dots are clearly visible, and yellowish pigment is dispersed within the cytoplasm. F) Growing trophozoite. An infected erythrocyte with major alteration in the shape, similar to that sometimes seen in P. vivax–infected erythrocytes. The cytoplasm is amoeboid, with hardly any pigment. Schüffner’s dots are prominent, and the host erythrocyte is enlarged. G) Growing trophozoite. The cytoplasm is amoeboid and appears relatively compact. Schüffner’s dots are dominant. Pigment is visible in small granules but appears more yellowish-brown and is scattered around in the cytoplasm. H) Near-mature trophozoite. The parasite is becoming more compact with an enlarged nucleus. No ring or amoeboid form is visible. Schüffner’s dots are very dense, and abundant yellowish-brown pigment is clearly visible in the cytoplasm. I) Mature microgametocyte. It is round and resembles that of P. vivax at the same stage. The nucleus is diffuse and takes up most of the parasite. The stippling of the host cell is forced toward the periphery, as seen for P. vivax. Microgametocytes stain reddish-purple (pink hue) in contrast to macrogametocytes, which stain light blue. The yellowish-brown pigment is scattered around in the parasite. Scale bars indicate 100 μm.

Malaria eradication: benefits, future scenarios and feasibility. Executive summary of the report of the WHO Strategic Advisory Group on Malaria Eradication

Sunday, September 1st, 2019Overview

After its 3-year study of trends and future projections for the factors and determinants that underpin malaria, the Strategic Advisory Group on Malaria Eradication (SAGme) reaffirms that eradication is a goal worth pursuing, likely to save millions of lives and billions of dollars. However, with our current tools, we are far from a malaria-free world.

In its executive summary, SAGme calls for more investment in research and development of new tools and approaches to fight malaria, stronger universal health coverage so that everyone can access the services they need, and better surveillance to guide a more targeted malaria response.

In Southeast Asia, drug-resistant strains of the malaria parasite are emerging

Wednesday, July 24th, 2019‘…..”Somehow antimalarial drug resistance always starts in that part of the world,” says Arjen Dondorp, who leads malaria research at the Mahidol Oxford Tropical Medicine Research Unit in Bangkok ………

“In the past, chloroquine resistance originated there. Sulfadoxine-pyrimethamine, the next generation of antimalarials — resistance to that originated there. And now the artemisinin resistance also was first detected in western Cambodia.”…..’

Accelerated evolution and spread of multidrug-resistant Plasmodium falciparum takes down the latest first-line antimalarial drug in southeast Asia

Chinese researchers are undertaking a mass drug administration, or MDA, which involves giving antimalarial pills to every man, woman, and child in Kenya all at once.

Monday, July 8th, 2019“…..But MDA is controversial for reasons of both science and ethics. There are concerns that it could lead to increased drug resistance, which could see malaria rise to levels not seen in decades. Others believe it’s unethical to give antimalarials to people who may not even have the disease—or who don’t wish to take them—though such qualms are dismissed in Kenya and elsewhere……”

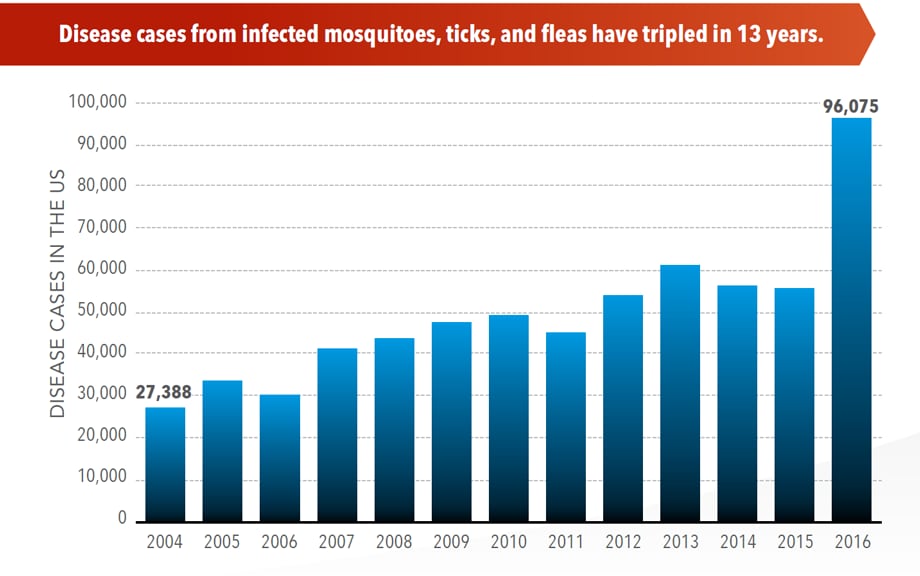

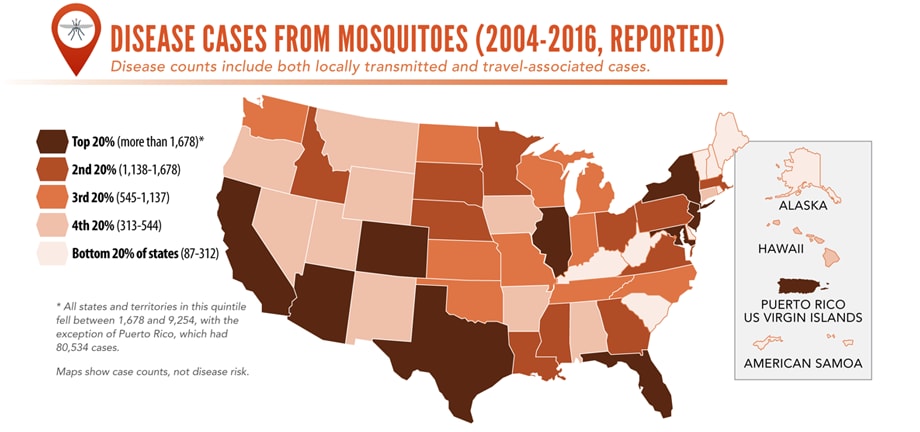

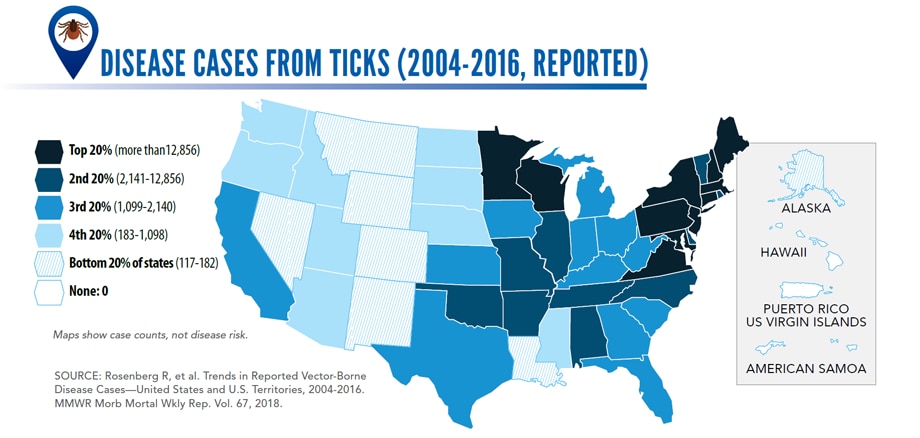

Illnesses on the rise from mosquito, tick, and flea bites

Sunday, June 2nd, 2019Almost everyone has been bitten by a mosquito, tick, or flea. These can be vectors for spreading pathogens (germs). A person who gets bitten by a vector and gets sick has a vector-borne disease, like dengue, Zika, Lyme, or plague. Between 2004 and 2016, more than 640,000 cases of these diseases were reported, and 9 new germs spread by bites from infected mosquitoes and ticks were discovered or introduced in the US. State and local health departments and vector control organizations are the nation’s main defense against this increasing threat. Yet, 84% of local vector control organizations lack at least 1 of 5 core vector control competencies. Better control of mosquitoes and ticks is needed to protect people from these costly and deadly diseases.

State and local public health agencies can

- Build and sustain public health programs that test and track germs and the mosquitoes and ticks that spread them.

- Train vector control staff on 5 core competencies for conducting prevention and control activities. http://bit.ly/2FG1OMwExternal

- Educate the public about how to prevent bites and control germs spread by mosquitoes, ticks, and fleas in their communities.

Increasing threat, limited capacity to respond

More cases in the US (2004-2016)

- The number of reported cases of disease from mosquito, tick, and flea bites has more than tripled.

- More than 640,000 cases of these diseases were reported from 2004 to 2016.

- Disease cases from ticks have doubled.

- Mosquito-borne disease epidemics happen more frequently.

More germs (2004-2016)

- Chikungunya and Zika viruses caused outbreaks in the US for the first time.

- Seven new tickborne germs can infect people in the US.

More people at risk

- Commerce moves mosquitoes, ticks, and fleas around the world.

- Infected travelers can introduce and spread germs across the world.

- Mosquitoes and ticks move germs into new areas of the US, causing more people to be at risk.

The US is not fully prepared

-

- Local and state health departments and vector control organizations face increasing demands to respond to these threats.

- More than 80% of vector control organizations report needing improvement in 1 or more of 5 core competencies, such as testing for pesticide resistance.

- More proven and publicly accepted mosquito and tick control methods are needed to prevent and control these diseases.

Altered fungus can kill malaria-carrying anopheles mosquito

Sunday, June 2nd, 2019“A fungus – genetically enhanced to produce spider toxin – can rapidly kill huge numbers of the mosquitoes that spread malaria, a study suggests.

Trials, which took place in Burkina Faso, showed mosquito populations collapsed by 99% within 45 days.

The researchers say their aim is not to make the insects extinct but to help stop the spread of malaria…..”

WHO: Malaria has been eliminated from Algeria and Argentina

Thursday, May 23rd, 2019“…..[T]here were now 38 countries and territories that have been declared free of the disease…..”