Archive for the ‘Melioidosis’ Category

Melioidosis & Hurricanes

Friday, October 11th, 2019

A systematic review of the peer-reviewed literature for human melioidosis cases between Jan 1, 1990, and Dec 31, 2015.

Tuesday, July 9th, 2019Global burden of melioidosis in 2015: a systematic review and data synthesis

- et al.

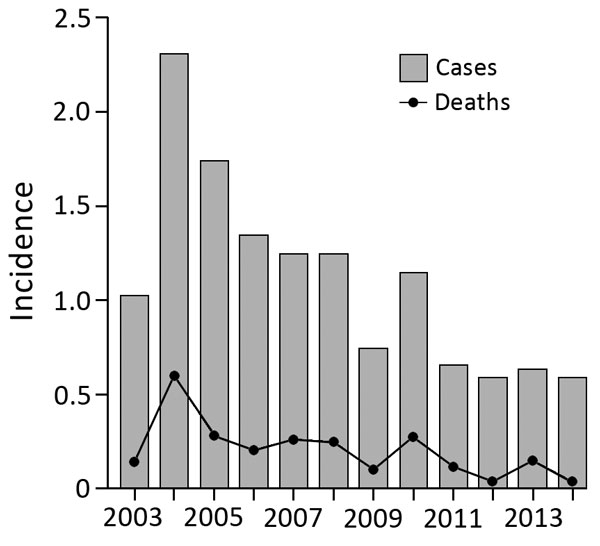

The overall death rate from melioidosis in Singapore was 18.4%, similar to that in the Northern Territory of Australia (14%).

Wednesday, December 20th, 2017Pang L, Harris P, Seiler RL, Ooi P, Cutter J, Goh K, et al. Melioidosis, Singapore, 2003–2014. Emerg Infect Dis. 2018;24(1):140-143. https://dx.doi.org/10.3201/eid2401.161449

Demographic characteristics of patients with melioidosis, Singapore, 2003–2014*

| Characteristic | 2003 | 2004 | 2005 | 2006 | 2007 | 2008 | 2009 | 2010 | 2011 | 2012 | 2013 | 2014 | Total (%)† |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. cases

|

42

|

96

|

74

|

59

|

57

|

60

|

37

|

58

|

34

|

31

|

34

|

32

|

614 |

CDC on Melioidosis

Monday, September 25th, 2017Melioidosis, also called Whitmore’s disease, is an infectious disease that can infect humans or animals. The disease is caused by the bacterium Burkholderia pseudomallei.

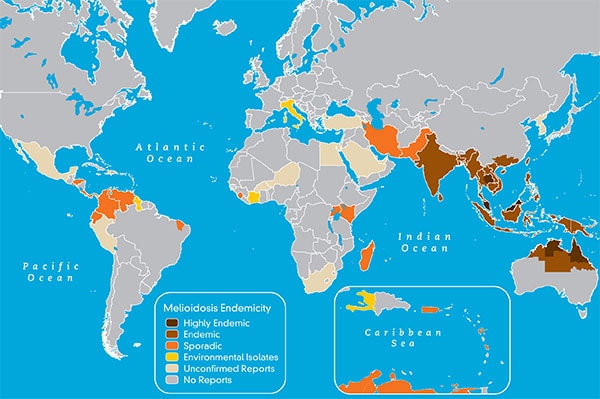

It is predominately a disease of tropical climates, especially in Southeast Asia and northern Australia where it is widespread. The bacteria causing melioidosis are found in contaminated water and soil. It is spread to humans and animals through direct contact with the contaminated source.

Transmission

People can get Melioidosis through direct contact with contaminated soil and surface waters.

People can get Melioidosis through direct contact with contaminated soil and surface waters.

Humans and animals are believed to acquire the infection by inhalation of contaminated dust or water droplets, ingestion of contaminated water, and contact with contaminated soil, especially through skin abrasions.

It is very rare for people to get the disease from another person. While a few cases have been documented, contaminated soil and surface water remain the primary way in which people become infected.

Besides humans, many animal species are susceptible to melioidosis, including:

- Sheep

- Goats

- Swine

- Horses

- Cats

- Dogs

- Cattle

Signs and Symptoms

There are several types of melioidosis infection, each with their own set of symptoms.

There are several types of melioidosis infection, each with their own set of symptoms.

However, it is important to note that melioidosis has a wide range of signs and symptoms that can be mistaken for other diseases such as tuberculosis or more common forms of pneumonia.

Localized Infection:

- Localized pain or swelling

- Fever

- Ulceration

- Abscess

Pulmonary Infection:

- Cough

- Chest pain

- High fever

- Headache

- Anorexia

Bloodstream Infection:

- Fever

- Headache

- Respiratory distress

- Abdominal discomfort

- Joint pain

- Disorientation

Disseminated Infection:

- Fever

- Weight loss

- Stomach or chest pain

- Muscle or joint pain

- Headache

- Seizures

The time between an exposure to the bacteria that causes the disease and the emergence of symptoms is not clearly defined, but may range from one day to many years; generally symptoms appear two to four weeks after exposure.

Although healthy people may get melioidosis, the major risk factors are:

- Diabetes

- Liver disease

- Renal disease

- Thalassemia

- Cancer or another immune-suppressing condition not related to HIV

- Chronic Lung disease (such as cystic fibrosis, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), and bronchiectasis)

Risk of Exposure

While melioidosis infection has taken place all over the world, Southeast Asia and northern Australia are the areas in which it is primarily found.

In the United States, confirmed cases reported in previous years have ranged from zero to five and have occurred among travelers and immigrants coming from places where the disease is widespread.

Moreover, it has been found among troops of all nationalities that have served in areas with widespread disease.

The greatest numbers of melioidosis cases are reported in:

- Thailand

- Malaysia

- Singapore

- Northern Australia

Though rarely reported, cases are thought to frequently occur in:

- Papua New Guinea

- Most of the Indian subcontinent

- Southern China

- Hong Kong

- Taiwan

- Vietnam

- Indonesia

- Cambodia

- Laos

- Myanmar (Burma)

Outside of Southeast Asia and Australia, cases have been reported in:

- The South Pacific (New Caledonia)

- Sri Lanka

- Mexico

- El Salvador

- Panama

- Ecuador

- Peru

- Guyana

- Puerto Rico

- Martinique

- Guadeloupe

- Brazil

- Parts of Africa and the Middle East

Treatment

When a melioidosis infection is diagnosed, the disease can be treated with the use of appropriate medication.

The type of infection(https://www.cdc.gov/melioidosis/signs-symptoms.html) and the course of treatment will impact long-term outcome. Treatment generally starts with intravenous (within a vein) antimicrobial therapy for 10-14 days, followed by 3-6 months of oral antimicrobial therapy.

Antimicrobial agents that have been effective against melioidosis include:

Intravenous therapy consists of:

- Ceftazidime administered every 6-8 hours

- OR

- Meropenem administered every 8 hours

Oral antimicrobial therapy consists of:

- Trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole taken every 12 hours

- OR

- Doxycycline taken every 12 hours

Patients with penicillin allergies should notify their doctor, who can prescribe an alternative treatment course.

Prevention

(https://www.cdc.gov/melioidosis/transmission/index.html)In areas where the disease is widespread (see map below), contact with contaminated soil or water can put people at risk for melioidosis.

(https://www.cdc.gov/melioidosis/transmission/index.html)In areas where the disease is widespread (see map below), contact with contaminated soil or water can put people at risk for melioidosis.

However, in these areas, there are things that certain groups of people can do to help minimize the risk of exposure:

- Persons with open skin wounds and those with diabetes or chronic renal disease are at increased risk for melioidosis and should avoid contact with soil and standing water.

- Those who perform agricultural work should wear boots, which can prevent infection through the feet and lower legs.

- Health care workers can use standard contact precautions (mask, gloves, and gown) to help prevent infection.

Endemicity of Meliodosis Infection

Healthcare Workers

Diagnosis

Melioidosis is diagnosed by isolating Burkholderia pseudomallei from blood, urine, sputum, skin lesions, or abscesses; or by detecting an antibody response to the bacteria.

Infection Classifications

Melioidosis can be categorized as an acute or localized infection, acute pulmonary infection, acute bloodstream infection, or disseminated infection. Sub-clinical infections are also possible. The incubation period (time between exposure and appearance of clinical symptoms) is not clearly defined, but may range from one day to many years; generally symptoms appear two to four weeks after exposure. Although healthy people may get melioidosis, the major risk factors are diabetes, liver disease, renal disease, thalassemia, cancer or another immune-suppressing condition not related to HIV.

Localized Infection

This form generally presents as an ulcer, nodule, or skin abscess and may result from inoculation through a break in the skin and may produce fever and general muscle aches. The infection may remain localized, or may progress rapidly through the bloodstream.

Pulmonary Infection

This is the most common form of presentation of the disease and can produce a clinical picture of mild bronchitis to severe pneumonia. The onset of pulmonary melioidosis typicall is marked by a high fever, headache, anorexia, and general muscle soreness. Chest pain is common, but a nonproductive or productive cough with normal sputum is the hallmark of this form of melioidosis. Cavitary lesions may be seen on chest X-ray, similar to those seen in pulmonary tuberculosis.

Bloodstream Infection

Patients with underlying risk factors such as diabetes and renal insufficiency are more likely to develop this form of the disease, which usually results in septic shock. The symptoms of bloodstream infection may include fever, headache, respiratory distress, abdominal discomfort, joint pain, muscle tenderness, and disorientation. This is typically an infection with rapid onset, and abscesses may be found throughout the body, most notably in the liver, spleen, or prostate.

Disseminated Infection

Disseminated melioidosis presents with abscess formation in various organs of the body, and may or may not be associated with sepsis. Organs involved typically include the liver, lung, spleen, and prostate; involvement of joints, bones, viscera, lymph nodes, skin, or brain may also occur. Disseminated infection may be seen in acute or chronic melioidosis. Signs and symptoms, in addition to fever, may include weight loss, stomach or chest pain, muscle or joint pain, and headache or seizure.

Bioterrorism

Melioidosis is a disease caused by germs that occur naturally in certain parts of the world(https://www.cdc.gov/melioidosis/risk.html), such as Southeast Asia and northern Australia. The only place these germs, called Burkholderia pseudomallei, occur naturally in the United States is Puerto Rico. Usually, people in the United States (outside of Puerto Rico) who get the disease have traveled and come into contact with the germs in one of these places where they occur naturally. One reason public health authorities study the disease is because it is possible that the germs that cause melioidosis might be used in a biological attack. A biological attack is the intentional release of germs that can sicken or kill people, livestock, or crops.

Melioidosis (Thailand to USA): Sore throat, fever, and bilateral thigh abscesses

Friday, September 22nd, 2017Mitchell PK, Campbell C, Montgomery MP, et al. Notes from the Field: Travel-Associated Melioidosis and Resulting Laboratory Exposures — United States, 2016. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2017;66:1001–1002. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.15585/mmwr.mm6637a8.

“….In mid-July 2016, a Pennsylvania resident aged 15 years who had recently returned from Thailand was treated by a pediatrician for sore throat, fever, and bilateral thigh abscesses at the sites of mosquito bites (Figure). She had traveled to northeast Thailand with nine other teens as part of an 18-day service-oriented trip run by an Ohio-based youth tour company that arranges travel to Thailand for approximately 500 persons annually. This trip included construction and agricultural activities and recreational mud exposures. The patient subsequently developed right inguinal lymphadenopathy and worsening abscesses, which prompted specimen collection for culture on August 25. This specimen was sent to a commercial laboratory in New Jersey, which identified Burkholderia pseudomallei, the causative organism of melioidosis, on August 30. The patient did not experience pneumonia or bacteremia, and recovered fully after 2 weeks of intensive therapy with parenteral ceftazidime and a 6-month outpatient course of eradication therapy with doxycycline….”

Thigh abscesses at the sites of mosquito bites in a Pennsylvania resident aged 15 years who had recently returned from Thailand, July 2016

Melioidosis estimate: 165,000 human melioidosis cases per year worldwide, from which 89,000 people die.

Tuesday, January 12th, 2016Melioidosis

INFECTIOUS AGENT

Burkholderia pseudomallei, a saprophytic gram-negative bacillus, is the causative agent of melioidosis. The bacteria are found in soil and water, widely distributed in tropical and subtropical countries.

TRANSMISSION

Through subcutaneous inoculation, ingestion, or inhalation; person-to-person transmission is extremely rare but may occur through contact with the blood or body fluids of an infected person.

EPIDEMIOLOGY

Melioidosis is endemic in Southeast Asia, Papua New Guinea, much of the Indian subcontinent, southern China, Hong Kong, and Taiwan and is considered highly endemic in northeast Thailand, Malaysia, Singapore, and northern Australia. Sporadic cases have been reported among residents of or travelers to Aruba, Colombia, Costa Rica, El Salvador, Guatemala, Guadeloupe, Honduras, Martinique, Mexico, Panama, Venezuela, and many other countries in the Americas, as well as Puerto Rico. In northern Brazil, clusters of melioidosis have been reported and are associated with periods of heavy rainfall. The risk is highest for adventure travelers, ecotourists, military personnel, construction and resource extraction workers, and other people whose contact with contaminated soil or water may expose them to the bacteria; infections have been reported in people who have spent less than a week in an endemic area. Risk factors for systemic melioidosis include diabetes, excessive alcohol use, chronic renal disease, chronic lung disease (such as associated with cystic fibrosis or chronic obstructive pulmonary disease), thalassemia, and malignancy or other non-HIV-related immune suppression.

CLINICAL PRESENTATION

Incubation period is generally 1–21 days, although it may extend for months or years; with a high inoculum, symptoms can develop in a few hours. Melioidosis may occur as a subclinical infection, localized infection (such as cutaneous abscess), pneumonia, meningoencephalitis, sepsis, or chronic suppurative infection. The latter may mimic tuberculosis, with fever, weight loss, productive cough, and upper lobe infiltrate, with or without cavitation. More than 50% of cases present with pneumonia.

DIAGNOSIS

Culture of B. pseudomallei from blood, sputum, pus, urine, synovial fluid, peritoneal fluid, or pericardial fluid is diagnostic. Indirect hemagglutination assay is a widely used serologic test but is not considered confirmatory. Diagnostic assistance is available through CDC (http://www.cdc.gov/ncezid/dhcpp/bacterial_special/zoonoses_lab.html).

TREATMENT

Ceftazidime, imipenem, or meropenem is used for initial treatment of 10–14 days, followed by 20–24 weeks of trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole. Relapse may be seen, especially in patients who received a shorter-than-recommended course of therapy.

PREVENTION

Travelers should use personal protective equipment such as waterproof boots and gloves to protect against contact with contaminated soil and water and thoroughly clean skin lacerations, abrasions, or burns that have been contaminated with soil or surface water.

CDC website: www.cdc.gov/melioidosis

BIBLIOGRAPHY

- Brilhante RS, Bandeira TJ, Cordeiro RA, Grangeiro TB, Lima RA, Ribeiro JF, et al. Clinical-epidemiological features of 13 cases of melioidosis in Brazil. J Clin Microbiol. 2012 Oct;50(10):3349–52.

- Currie BJ, Dance DA, Cheng AC. The global distribution of Burkholderia pseudomallei and melioidosis: an update. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg. 2008 Dec;102 Suppl 1:S1–4.

- Inglis TJ, Rolim DB, Sousa Ade Q. Melioidosis in the Americas. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2006 Nov;75(5):947–54.

- Limmathurotsakul D, Kanoksil M, Wuthiekanun V, Kitphati R, deStavola B, Day NP, et al. Activities of daily living associated with acquisition of melioidosis in northeast Thailand: a matched case-control study. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2013;7(2):e2072.

- O’Sullivan BP, Torres B, Conidi G, Smole S, Gauthier C, Stauffer KE, et al. Burkholderia pseudomallei infection in a child with cystic fibrosis: acquisition in the Western Hemisphere. Chest. 2011 Jul;140(1):239–42.

- Wiersinga WJ, Currie BJ, Peacock SJ. Melioidosis. N Engl J Med. 2012 Sep 13;367(11):1035–44.