Nipah virus (NiV) is an emerging zoonotic virus (a virus transmitted to humans from animals). In infected people, Nipah virus causes a range of illnesses from asymptomatic (subclinical) infection to acute respiratory illness and fatal encephalitis. NiV can also cause severe disease in animals such as pigs, resulting in significant economic losses for farmers.

Nipah virus is closely related to Hendra virus. Both are members of the genus Henipavirus, a new class of virus in the Paramyxoviridae family.

Although Nipah virus has caused only a few outbreaks, it infects a wide range of animals and causes severe disease and death in people, making it a public health concern.

Past Outbreaks

Nipah virus was first recognized in 1999 during an outbreak among pig farmers in Kampung Sungai Nipah, Malaysia. No new outbreaks have been reported in Malaysia and Singapore since 1999.

NiV was first recognized in Bangladesh in 2001 and nearly annual outbreaks have occurred in that country since, with disease also identified periodically in eastern India.

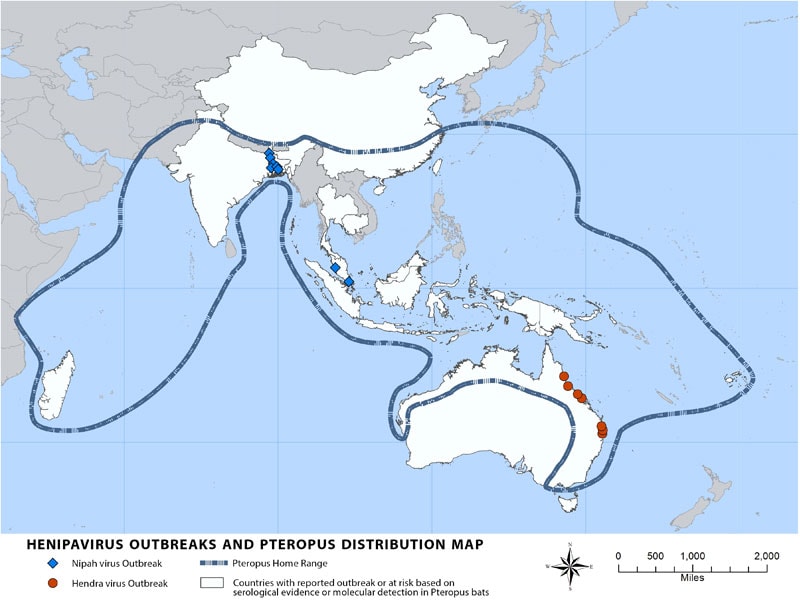

Other regions may be at risk for NiV infection, as serologic evidence for NiV has been found in the known natural reservoir (Pteropus bat species) and several other bat species in a number of countries, including Cambodia, Thailand, Indonesia, Madagascar, Ghana and the Philippines.

Transmission

NiV is a zoonotic virus (a virus transmitted to humans from animals). During the initial outbreaks in Malaysia and Singapore, most human infections resulted from direct contact with sick pigs or their contaminated tissues. Transmission is thought to have occurred via respiratory droplets, contact with throat or nasal secretions from the pigs, or contact with the tissue of a sick animal.

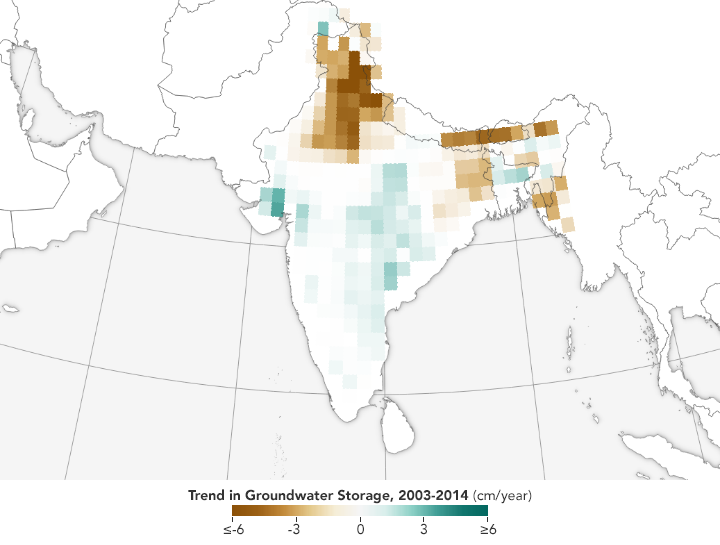

In the Bangladesh and India outbreaks, consumption of fruits or fruit products (e.g. raw date palm juice) contaminated with urine or saliva from infected fruit bats was the most likely source of infection.

Limited human to human transmission of NiV has also been reported among family and care givers of infected NiV patients. During the later outbreaks in Bangladesh and India, Nipah virus spread directly from human-to-human through close contact with people’s secretions and excretions. In Siliguri, India, transmission of the virus was also reported within a health-care setting (nosocomial), where 75% of cases occurred among hospital staff or visitors. From 2001 to 2008, around half of reported cases in Bangladesh were due to human-to-human transmission through providing care to infected patients.

Signs and symptoms

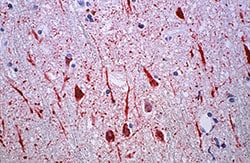

Human infections range from asymptomatic infection, acute respiratory infection (mild, severe), and fatal encephalitis. Infected people initially develop influenza-like symptoms of fever, headaches, myalgia (muscle pain), vomiting and sore throat. This can be followed by dizziness, drowsiness, altered consciousness, and neurological signs that indicate acute encephalitis. Some people can also experience atypical pneumonia and severe respiratory problems, including acute respiratory distress. Encephalitis and seizures occur in severe cases, progressing to coma within 24 to 48 hours.

The incubation period (interval from infection to the onset of symptoms) is believed to range between from 4-14 days. However an incubation period as long as 45 days has been reported.

Most people who survive acute encephalitis make a full recovery, but long term neurologic conditions have been reported in survivors. Approximately 20% of patients are left with residual neurological consequences such as seizure disorder and personality changes. A small number of people who recover subsequently relapse or develop delayed onset encephalitis.

The case fatality rate is estimated at 40% to 75%; however, this rate can vary by outbreak depending on local capabilities for epidemiological surveillance and clinical management.

Diagnosis

Initial signs and symptoms of NiV infection are non-specific and the diagnosis is often not suspected at the time of presentation. This can hinder accurate diagnosis and creates challenges in outbreak detection and institution of effective and timely infection control measures and outbreak response activities.

In addition, clinical sample quality, quantity, type, timing of collection and the time necessary to transfer samples from patients to the laboratory can affect the accuracy of laboratory results.

NiV infection can be diagnosed together with clinical history during the acute and convalescent phase of the disease. Main tests including real time polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) from bodily fluids as well as antibody detection via ELISA. Different tests include:

- enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA)

- polymerase chain reaction (PCR) assay

- ·virus isolation by cell culture.

Treatment

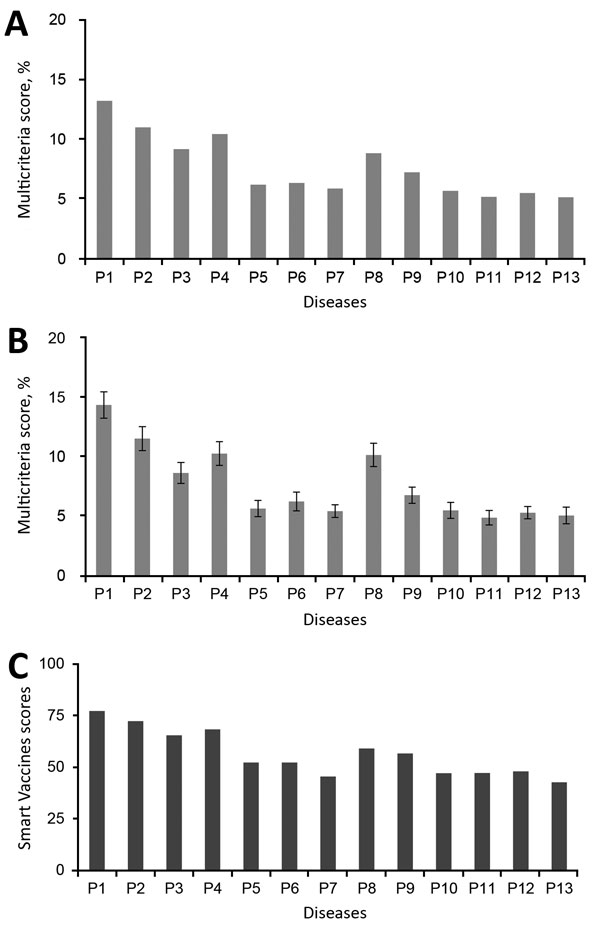

There are currently no drugs or vaccines specific for NiV infection although this is a priority disease on the WHO R&D Blueprint. Intensive supportive care is recommended to treat severe respiratory and neurologic complications.

Natural host: fruit bats

Fruit bats of the family Pteropodidae – particularly species belonging to the Pteropus genus – are the natural hosts for Nipah virus. There is no apparent disease in fruit bats.

It is assumed that the geographic distribution of Henipaviruses overlaps with that of Pteropus category. This hypothesis was reinforced with the evidence of Henipavirus infection in Pteropus bats from Australia, Bangladesh, Cambodia, China, India, Indonesia, Madagascar, Malaysia, Papua New Guinea, Thailand and Timor-Leste.

African fruit bats of the genus Eidolon, family Pteropodidae, were found positive for antibodies against Nipah and Hendra viruses, indicating that these viruses might be present within the geographic distribution of Pteropodidae bats in Africa.

Nipah virus in domestic animals

Nipah outbreaks in pigs and other domestic animals (horses, goats, sheep, cats and dogs) were first reported during the initial Malaysian outbreak in 1999.

Nipah virus is highly contagious in pigs. Pigs are infectious during the incubation period, which lasts from 4 to 14 days.

An infected pig can exhibit no symptoms, but some develop acute feverish illness, labored breathing, and neurological symptoms such as trembling, twitching and muscle spasms. Generally, mortality was low except in young piglets. These symptoms are not dramatically different from other respiratory and neurological illnesses of pigs. Nipah should be suspected if pigs also have an unusual barking cough or if human cases of encephalitis are present.

Prevention

Controlling Nipah virus in domestic animals

Currently, there are no vaccines available against Nipah virus. Routine and thorough cleaning and disinfection of pig farms (with appropriate detergents) may be effective in preventing infection.

If an outbreak is suspected, the animal premises should be quarantined immediately. Culling of infected animals – with close supervision of burial or incineration of carcasses – may be necessary to reduce the risk of transmission to people. Restricting or banning the movement of animals from infected farms to other areas can reduce the spread of the disease.

As Nipah virus outbreaks in domestic animals have preceded human cases, establishing an animal health surveillance system, using a One Health approach, to detect new cases is essential in providing early warning for veterinary and human public health authorities.

Reducing the risk of infection in people

In the absence of a licensed vaccine, the only way to reduce infection in people is by raising awareness of the risk factors and educating people about the measures they can take to reduce exposure to and decrease infection from NiV.

Public health educational messages should focus on the following:

- Reducing the risk of bat-to-human transmission: Efforts to prevent transmission should first focus on decreasing bat access to date palm sap and to other fresh food products. Keeping bats away from sap collection sites with protective coverings (e.g., bamboo sap skirts) may be helpful.Freshly collected date palm juice should be boiled and fruits should be thoroughly washed and peeled before consumption.

- Reducing the risk of animal-to-human transmission: Gloves and other protective clothing should be worn while handling sick animals or their tissues, and during slaughtering and culling procedures. As much as possible, people should avoid being in contact with infected pigs.

- Reducing the risk of human-to-human transmission: Close unprotected physical contact with Nipah virus-infected people should be avoided. Regular hand washing should be carried out after caring for or visiting sick people.

Controlling infection in health-care settings

- Health-care workers caring for patients with suspected or confirmed NiV infection, or handling specimens from them, should implement standard infection control precautions for all patients at all times

- As human-to-human transmission in particular nosocomial transmission have been reported, contact and droplet precautions should be used in addition to standard precautions.

- Samples taken from people and animals with suspected NiV infection should be handled by trained staff working in suitably equipped laboratories.