Objectives

To study the associations between Influenza like illness (ILI) and socioeconomic status (SES), gender and wave during the 1918-19 influenza pandemic.

“……It was the third time the committee, consisting of leading virologists, bacteriologists and infectious disease experts, had met to consider diseases with epidemic or pandemic potential. But when the 2018 list was released two weeks ago it included an entry not seen in previous years.

*Diseases posing significant risk of an international public health emergency for which there is no, or insufficient, countermeasures. Source: World Health Organization (WHO), 2018

“…..To develop a universal influenza vaccine, NIAID will focus resources on three key areas of influenza research: improving the understanding of the transmission, natural history and pathogenesis of influenza infection; precisely characterizing how protective influenza immunity occurs and how to tailor vaccination responses to achieve it; and supporting the rational design of universal influenza vaccines, including designing new immunogens and adjuvants to boost immunity and extend the duration of protection.…..”

Emily J Erbelding, Diane Post, Erik Stemmy, Paul C Roberts, Alison Deckhut Augustine, Stacy Ferguson, Catharine I Paules, Barney S Graham, Anthony S Fauci; A Universal Influenza Vaccine: The Strategic Plan for the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, The Journal of Infectious Diseases, , jiy103, https://doi.org/10.1093/infdis/jiy103

“…..Mounting epidemiological evidence supports the occurrence of a mild herald pandemic wave in the spring and summer of 1918 in North America and Europe, several months before the devastating autumn outbreak that killed an estimated 2% of the global population [1]. These epidemiological findings corroborate the anecdotal observations of contemporary clinicians who reported widespread influenza outbreaks in Spring and Summer 1918, with sporadic occurrence of unusually severe clinical manifestations in young adults.……”

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=lcR0TmTT6Eo

| Full report (PDF) |

The health sector in the United States would be far better positioned to manage medical care needs during emergencies of any scale by empowering existing healthcare coalitions to connect community resilience efforts with a network of hospitals equipped to handle disasters, according to a new report by the Johns Hopkins Center for Health Security.

The report, “A Framework for Healthcare Disaster Resilience: A View to the Future,” was released at a February 22 event at the National Press Club.

“We wondered what an optimal system would look like and how we would get there,” said Eric Toner, MD, a senior scholar at the Center and principal investigator on the report. “Change is needed, but the change should be evolutionary, not revolutionary. We need to build on the resources we already have.”

Toner’s coauthors on the report are Center colleagues Monica Schoch-Spana, PhD, Richard Waldhorn, MD, Matthew Shearer, MPH, and Tom Inglesby, MD. The team first identified four distinct categories of disasters that could cause significant illness or injury, and for which preparedness gaps likely exist due to differing operational challenges and resource needs. A subsequent gap analysis confirmed their theory: While the US health sector is reasonably well prepared for relatively small mass injury/illness events that happen frequently (e.g., tornadoes, local disease outbreaks), it is less prepared for large-scale disasters (e.g., hurricanes) and complex mass casualty events (e.g., bombings) and poorly prepared for catastrophic health events (e.g., severe pandemics, large-scale bioterrorism).

These gaps, the authors say, exist as a result of the absence of strategies above and beyond the traditional all-hazards approach to improving US health sector preparedness. The authors define the US health sector as all entities and personnel that are involved in people’s health, combined with the community-based organizations that support these entities and represent the patients who receive services from them. This network’s incident-specific response actions and capabilities vary widely across the four categories of disasters.

The authors offer four recommendations for closing preparedness gaps unique to the US health sector:

Build a Culture of Resilience: Launch a new federal program that encourages and incentivizes local grassroots and community-based organizations to become more involved in efforts to enhance the disaster resilience of the local health sector. This Culture of Resilience program would engage organizations traditionally not involved in health sector preparedness.

Create a network of disaster centers of excellence: Connect geographically distributed, large academic medical centers and designate them Disaster Resource Hospitals by setting rigorous standards, providing direct funding, and requiring accountability. These hospitals would be a source of remote, real-time clinical expertise, continuing education and training, and expertise for public health officials, among other benefits.

Increase support for healthcare coalitions (HCCs): Already successful healthcare coalitions comprising well-prepared hospitals, health departments, EMS providers, and emergency management need additional funding to engage other organizations inside the health sector (e.g., nursing homes) and outside the health sector (e.g., faith-based community groups) in preparedness work. HCC-led collaboration would then help integrate disaster resource hospital capabilities into preparedness and response for the overall coalition, and link community resilience efforts back to disaster research hospitals.

Designate a federal coordinator for catastrophic health event preparedness: Within the Office of the Assistant Secretary for Preparedness and Response (ASPR) in the US Department of Health and Human Services, dedicate a group responsible only for preparing the nation for catastrophic health events. This group would coordinate existing decentralized healthcare preparedness initiatives in ASPR and provide a vision for strengthening preparedness in the future, with an increased focus on resilience.

“It is now widely recognized that resilience of communities and systems should be the goal rather than just preparedness,” the authors wrote in the report. “Resilient communities seek to resist the impact of disasters, recover promptly to normal operational capacity, and learn how better to withstand future events.”

The report concludes with policy requirements for each of these recommendations. There is opportunity for some of the requirements to be incorporated into the Pandemic and All-Hazards Preparedness Act reauthorization this year.

“There needs to be more focus at the federal level, particularly on catastrophic health events,” Toner said to an audience of more than 40 people in the health security policy community in attendance at the Press Club.

Guest speakers at the event included Luciana Borio, MD, director of global health security and biological threats for the White House National Security Council; Sally Phillips, PhD, deputy assistant secretary for policy in the Office of the Assistant Secretary for Preparedness and Response at the US Department of Health and Human Services; and Linda Langston, director of strategic relations at the National Association of Counties.

To inform their work, the project team reviewed five years of published literature and conducted a series of working group meetings, a focus group, and interviews with more than 40 subject matter experts and thought leaders.

This project was funded by the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation.

“…..Although only 3 hemagglutinin (HA) subtypes of influenza (H1, H2, and H3) are known to have caused human pandemics, the emergence and spread of influenza A(H5N1) and, more recently, influenza A(H7N9), with associated high death rates in humans, are of great concern. If these or other influenza A viruses not currently circulating among humans develop the capability to transmit efficiently among humans, they pose a risk for causing a pandemic that could be associated with high rates of illness and death…….

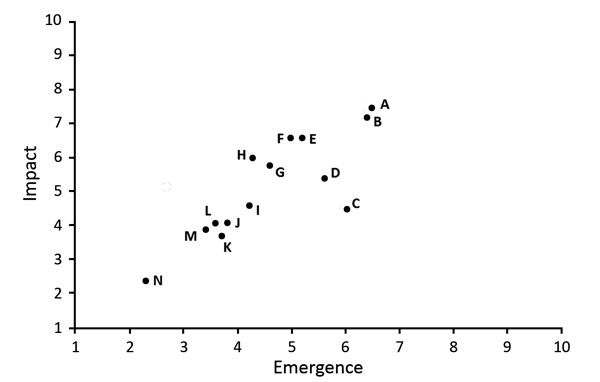

The IRAT uses a common decision analysis approach that incorporates input from multiple elements or attributes, applies a weighting scheme, and generates a score to compare various options or decisions (11). In regard to the evaluation of animal-origin influenza viruses for their potential human pandemic risk, 2 specific questions were developed related to the potential risk for emergence and consequent potential impact: 1) What is the risk that a virus not currently circulating in humans has the potential for sustained human-to-human transmission? (emergence question); and 2) If a virus were to achieve sustained human-to-human transmission, what is the risk that a virus not currently circulating among humans has the potential for substantial impact on public health? (impact question).

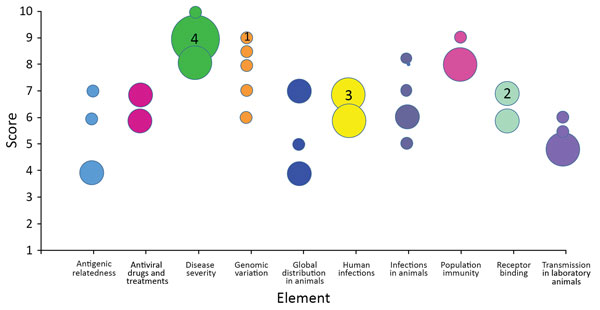

In developing the IRAT, a working group of international influenza experts in influenza virology, animal health, human health, and epidemiology identified 10 risk elements and definitions. These elements were described previously (10); in brief, they include virus properties (genomic variation, receptor-binding properties, transmissibility in animal models, and antiviral treatment susceptibility) and host properties (population immunity, disease severity, and antigenic relationship to vaccines). The final 3 elements are based on the epidemiologic and ecologic evidence: infection in humans, infections in animals, and global distribution in animals. These elements are used to answer the 2 risk questions to evaluate an influenza virus of interest. The 10 elements are ranked and weighted on the basis of their perceived importance to answering the specific risk questions and an aggregate risk score is generated……….“

Individual subject-matter expert point scores by element for the May 2017 scoring of influenza A(H7N9) virus, A/Hong Kong/125/2017, based on risk element definitions. Circles indicate individual point scores; circle sizes (examples indicated by a number inside) correspond to the frequency of each point score.

Comparison of average emergence and impact scores for 14 animal-origin influenza viruses using the Influenza Risk Assessment Tool. Circle represents each virus: A, H7N9 A/Hong Kong/125/2017; B, H7N9 A/Shanghai/02/2013; C, H3N2 variant A/Indiana/08/2011; D, H9N2 G1 lineage A/Bangladesh/0994/2011; E, H5N1 clade 1 A/Vietnam/1203/2004; F, H5N6 A/Yunnan/14564/2015-like; G, H7N7 A/Netherlands/2019/2003; H, H10N8 A/Jiangxi-Donghu/346/2013; I, H5N8 A/gyrfalcon/Washington/41088/2014; J, H5N2 A/Northern pintail/Washington/40964/2014; K, H3N2 A/canine/Illinois/12191/2015; L, H5N1 A/American green-winged teal/Washington/1957050/2014; M, H7N8 A/turkey/Indiana/1573-2/2016; N, H1N1 A/duck/New York/1996. Additional information about virus scores and individual viruses is available at https://www.cdc.gov/flu/pandemic-resources/monitoring/irat-virus-summaries.htm.

| Burke SA, Trock SC. Use of Influenza Risk Assessment Tool for Prepandemic Preparedness. Emerg Infect Dis. 2018;24(3):471-477. https://dx.doi.org/10.3201/eid2403.171852 |

Is the U.S. Export Economy at Risk from Global Infectious Outbreaks?

New CDC analysis examines potential threat to markets and jobs

For Immediate Release

Tuesday, February 13, 2018

Contact:Media Relations

(404) 639-3286

In addition to tragic loss of life, the next global infectious disease outbreak could harm the U.S. export economy and threaten U.S. jobs—even if the disease never reaches our shores. Two Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) articles published in Health Security analyze the risks and show potential losses to the American export economy from an overseas outbreak.

The two articles underscore the importance of the President’s request this week for $59 million in support of the Global Health Security Agenda (GHSA) in Fiscal Year 2019.

“The President’s Budget request of $59 million for Fiscal Year 2019 for GHSA demonstrates the Administration’s commitment to global health security and provides an important bridge to the extension of the GHSA announced in October 2017 in Uganda,” said Anne Schuchat, M.D., acting Director of CDC. “This new funding continues the U.S. commitment to this multi-national effort and supplements U.S. Government multisector support for this initiative.”

The first of the two articles, Relevance of Global Health Security to the U.S. Export Economy, the potential disruption to the U.S. export economy if an infectious disease outbreak were to take hold in CDC’s 49 global health security priority countries.

Using 2015 U.S. Department of Commerce data, the article assesses the value of U.S. exports to the 49 countries and the number of jobs supported by those exports, finding that:

CDC’s global health security efforts stop outbreaks where they start to protect health worldwide, in turn protecting demand for U.S. exports and the jobs they support in America.

The second article, Impact of Hypothetical Infectious Disease Outbreak on U.S. Exports and Export-Based Jobs, examines what could happen to the U.S. economy if an epidemic were to strike a key region, such as Southeast Asia. The article demonstrates how an epidemic spanning nine countries in Asia could cost the U.S. over $40 billion in export revenues and put more than 1 million U.S. jobs at risk.2

Southeast Asia is at greater risk for an emerging infectious disease event due to zoonotic, drug-resistant, and vector-borne diseases. Exports to Asia support the largest number of U.S. export-related jobs, which is why a large-scale infectious disease outbreak in this region could significantly disrupt the U.S. export economy.

The article illustrates the potential impact on the U.S. economy of an outbreak in just one affected country, and then expands the hypothetical scenario to look at what might happen if the outbreak were to spread across the region. Economic models used in the scenario take into account a large number of variables, including the interconnections between sectors of an economy and the trade between countries.

“The results of this hypothetical scenario show that the U.S. economy is better protected when public health threats are quickly identified and contained,” said Rebecca Martin, Ph.D., director, CDC’s Center for Global Health.

These articles offer valuable findings for policymakers and partners to consider when prioritizing programs to improve prevention, detection, and response to outbreaks around the world, and thereby reduce the potential threat to global markets and U.S. jobs.

Impact of a Hypothetical Infectious Disease Outbreak on US Exports and Export-Based Jobs

Zoe Bambery, Cynthia H. Cassell, Rebecca E. Bunnell, Kakoli Roy, Zara Ahmed, Rebecca L. Payne, and Martin I. Meltzer

Health Security Volume 16, Number 1, 2018 Mary Ann Liebert, Inc. DOI: 10.1089/hs.2017.0052

We estimated the impact on the US export economy of an illustrative infectious disease outbreak scenario in Southeast Asia that has 3 stages starting in 1 country and, if uncontained, spreads to 9 countries. We used 2014-2016 West Africa Ebola epidemic–related World Bank estimates of 3.3% and 16.1% reductions in gross domestic product (GDP). We also used US Department of Commerce job data to calculate export-related jobs at risk to any outbreak-related disruption in US exports. Assuming a direct correlation between GDP reductions and reduced demand for US exports, we estimated that the illustrative outbreak would cost from $16 million to $27 million (1 country) to $10 million to $18 billion (9 countries) and place 1,500 to almost 1.4 million export-related US jobs at risk. Our analysis illustrates how global health security is enhanced, and the US economy is protected, when public health threats are rapidly detected and contained at their source.

1918 H1N1 influenza virus replicates and induces pro-inflammatory cytokine responses in extra-respiratory tissues of ferrets.

The Journal of Infectious Diseases, jiy003, https://doi.org/10.1093/infdis/jiy003

Published: 10 January 2018

“….1918 H1N1 virus spread to, and induced cytokine responses in tissues outside the respiratory tract, which likely contributed to the severity of infection. Moreover, our data support the suggested link between 1918 H1N1 infection and CNS disease.….”

Mamelund, S.-E. (), 1918 pandemic morbidity: the first wave hits the poor, the second wave hits the rich. Influenza Other Respi Viruses. Accepted Author Manuscript. doi:10.1111/irv.12541

To study the associations between Influenza like illness (ILI) and socioeconomic status (SES), gender and wave during the 1918-19 influenza pandemic.

Availability of incidence data on the 1918-19 pandemic is scarce, in particular for waves other than the “fall wave” October-December 1918. Here, an overlooked survey from Bergen, Norway (n=10,633), is used to study differences in probabilities of ILI and ILI probability ratios by apartment size as a measure of SES and gender for three waves including the waves prior to and after the “fall wave”.

SES was negatively associated with ILI in the first wave, but positively associated in the second wave. At all SES levels, men had the highest ILI in the summer, while women had the highest ILI in the fall. There were no SES or gender differences in ILI in the winter of 1919.

For the first time it is documented a crossover in the role of socioeconomic status in 1918 pandemic morbidity. The poor came down with influenza first, while the rich with less exposure in the first wave had the highest morbidity in the second wave. The study suggest that socioeconomically disadvantaged should be prioritized if vaccines are of limited availability in a future pandemic.

“…..The risks posed by AMR have continued to intensify in the five years since the 2013 report. Numerous welcome initiatives have been launched, but concrete successes in addressing the two drivers identified above remain elusive. We still face two trends that spell potential disaster: new classes of drugs are not being invented and resistance to existing drugs continues to spread inexorably. The stakes are incredibly high—if resistance overtakes all our available antibiotics, it would spell the “the end of modern medicine”.…..”

The Pharmaceutical Journal. 2017. “Chief Medical Officer Warns Antibiotic Resistance Could Signal ‘End of Modern Medicine’”. The Pharmaceutical Journal. 17 October 2017. http://www.pharmaceutical-journal.com/news-and-analysis/news/chief-medical-officer-warns-antibiotic-resistance-could-signal-end-of-modern-medicine/20203745.article

Selected AMR Rates

Resistance of Staphylococcus aureus to Oxadcillin (MRSA), % Resistant (invasive isolates)

Resistance of Klebsiella pneumoniae to Cephalosporins (3rd gen), % Resistant (invasive isolates)

Source: Figure courtesy Center for Disease Dynamics, Economics and Policy. Used with permission via Creative Commons license. https://resistancemap.cddep.org/AntibioticResistance.php

Note: Countries in white indicate no data available.