Rift Valley fever (RVF) is a viral zoonosis that primarily affects animals but also has the capacity to infect humans. Infection can cause severe disease in both animals and humans. The disease also results in significant economic losses due to death and abortion among RVF-infected livestock.

RVF virus is a member of the Phlebovirus genus. The virus was first identified in 1931 during an investigation into an epidemic among sheep on a farm in the Rift Valley of Kenya.

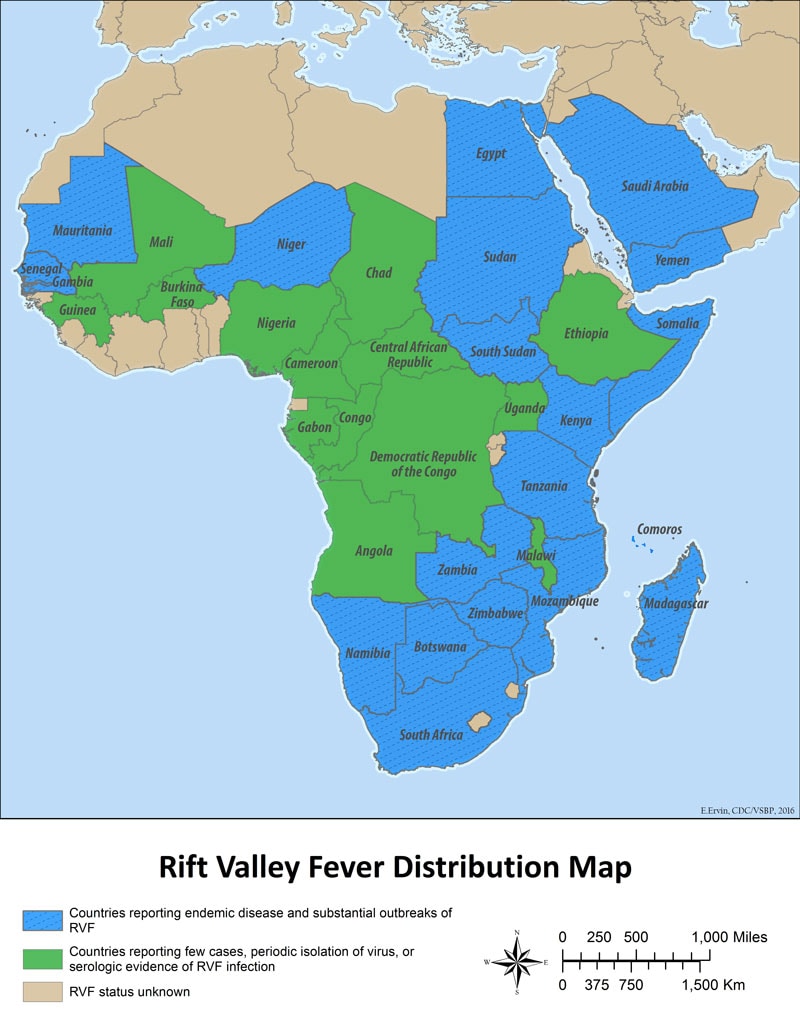

Since then, outbreaks have been reported in sub-Saharan Africa. In 1977 an explosive outbreak was reported in Egypt, the RVF virus was introduced to Egypt via infected livestock trade along the Nile irrigation system. In 1997–98, a major outbreak occurred in Kenya, Somalia and Tanzania following El Niño event and extensive flooding. Following infected livestock trade from the horn of Africa, RVF spread in September 2000 to Saudi Arabia and Yemen, marking the first reported occurrence of the disease outside the African continent and raising concerns that it could extend to other parts of Asia and Europe.

Transmission in humans

The majority of human infections result from direct or indirect contact with the blood or organs of infected animals. The virus can be transmitted to humans through the handling of animal tissue during slaughtering or butchering, assisting with animal births, conducting veterinary procedures, or from the disposal of carcasses or fetuses. Certain occupational groups such as herders, farmers, slaughterhouse workers, and veterinarians are therefore at higher risk of infection.

The virus infects humans through inoculation, for example via a wound from an infected knife or through contact with broken skin, or through inhalation of aerosols produced during the slaughter of infected animals.

There is some evidence that humans may become infected with RVF by ingesting the unpasteurized or uncooked milk of infected animals.

- Human infections have also resulted from the bites of infected mosquitoes, most commonly the Aedes and Culex mosquitoes and the transmission of RVF virus by hematophagous (blood-feeding) flies is also possible.

- To date, no human-to-human transmission of RVF has been documented, and no transmission of RVF to health care workers has been reported when standard infection control precautions have been put in place.

- There has been no evidence of outbreaks of RVF in urban areas.

Clinical features in humans

Mild form of RVF in humans

The following are clinical features of the mild form of RVF in humans:

- The incubation period (the interval from infection to onset of symptoms) for RVF varies from 2 to 6 days.

- Those infected either experience no detectable symptoms or develop a mild form of the disease characterized by a feverish syndrome with sudden onset of flu-like fever, muscle pain, joint pain and headache. Some patients develop neck stiffness, sensitivity to light, loss of appetite and vomiting; in these patients the disease, in its early stages, may be mistaken for meningitis.

- The symptoms of RVF usually last from 4 to 7 days, after which time the immune response becomes detectable with the appearance of antibodies and the virus disappears from the blood.

Severe form of RVF in humans

While most human cases are relatively mild, a small percentage of patients develop a much more severe form of the disease. This usually appears as 1 or more of 3 distinct syndromes: ocular (eye) disease (0.5–2% of patients), meningoencephalitis (less than 1% of patients) or haemorrhagic fever (less than 1% of patients).

The following are clinical features of the severe form of RVF in humans:

- Ocular form: In this form of the disease, the usual symptoms associated with the mild form of the disease are accompanied by retinal lesions. The onset of the lesions in the eyes is usually 1 to 3 weeks after appearance of the first symptoms. Patients usually report blurred or decreased vision. The disease may resolve itself with no lasting effects within 10 to 12 weeks. However, when the lesions occur in the macula, 50% of patients will experience a permanent loss of vision. Death in patients with only the ocular form of the disease is uncommon.

- Meningoencephalitis form: The onset of the meningoencephalitis form of the disease usually occurs 1 to 4 weeks after the first symptoms of RVF appear. Clinical features include intense headache, loss of memory, hallucinations, confusion, disorientation, vertigo, convulsions, lethargy and coma. Neurological complications can appear later (after more than 60 days). The death rate in patients who experience only this form of the disease is low, although residual neurological deficit, which may be severe, is common.

- Haemorrhagic fever form: The symptoms of this form of the disease appear 2–4 days after the onset of illness, and begin with evidence of severe liver impairment, such as jaundice. Subsequently signs of haemorrhage then appear such as vomiting blood, passing blood in the faeces, a purpuric rash or ecchymoses (caused by bleeding in the skin), bleeding from the nose or gums, menorrhagia and bleeding from venepuncture sites. The case-fatality ratio for patients developing the haemorrhagic form of the disease is high at approximately 50%. Death usually occurs 3 to 6 days after the onset of symptoms. The virus may be detectable in the blood for up to 10 days, in patients with the hemorrhagic icterus form of RVF.

The total case fatality rate has varied widely between different epidemics but, overall, has been less than 1% in those documented. Most fatalities occur in patients who develop the haemorrhagic icterus form.

Outbreaks that have occurred since 2000:

Severe form of RVF in humans

2016, Republic of Niger: As of 11 October 2016, Ministry of Health reported 105 suspected cases including 28 deaths of RVF in humans in Tahoua region.

2012 Republic of Mauritania: The Ministry of Health in Mauritania declared an outbreak of RVF on 4 October 2012. From 16 September 2012 (the date of onset of the index case) to 13 November 2012, a total of 36 cases, including 18 deaths were reported from 6 regions.

2010, Republic of South Africa: From February to July 2010, the Government of South Africa reported 237 confirmed cases of RVF in humans, including 26 deaths from 9 provinces.

2008–2009, Madagascar: From December 2008 to May 2009, the Ministry of Health, Madagascar reported 236 suspected cases including 7 deaths.

2008, Madagascar: The Ministry of Health, Madagascar reported an outbreak of RVF on 17 April 2008. From January to June 2008, a total of 476 suspected cases of RVF including 19 deaths were reported from 4 provinces.

2007, Sudan: The Federal Ministry of Health, Sudan, reported an outbreak of RVF on 28 October 2008. A total of 738 cases, including 230 deaths, were reported in Sudan between November 2007 and January 2008.

2006, Kenya, Somalia and Tanzania: From 30 November 2006 to 12 March 2007, a total of 684 cases including 234 deaths from RVF was reported in Kenya. From 19 December 2006 to 20 February 2007, a total of 114 cases including 51 deaths was reported in Somalia. From 13 January to 3rd May 2007, a total of 264 cases including 109 deaths was reported in Tanzania.

2003, Egypt: In 2003 there were 148 cases including 27 deaths of RVF reported by the Ministry of Health of Egypt.

2000, Saudi Arabia and Yemen: There were 516 cases with 87 deaths of RVF reported by the Ministry of Health of Saudi Arabia. In 2000, the Ministry of Public Health in Yemen reported 1087 suspected cases, including 121 deaths.

Diagnosis

Because the symptoms of Rift Valley fever are varied and non-specific, clinical diagnosis is often difficult, especially early in the course of the disease. Rift Valley fever is difficult to distinguish from other viral haemorrhagic fevers as well as many other diseases that cause fever, including malaria, shigellosis, typhoid fever, and yellow fever.

Definitive diagnosis requires testing that is available only in reference laboratories. Laboratory specimens may be hazardous and must be handled with extreme care. Rift Valley fever virus infections can only be diagnosed definitively in the laboratory using the following tests:

- reverse transcriptase polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) assay

- IgG and IgM antibody enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA)

- virus isolation by cell culture.

Treatment and vaccines

As most human cases of RVF are relatively mild and of short duration, no specific treatment is required for these patients. For the more severe cases, the predominant treatment is general supportive therapy.

An inactivated vaccine has been developed for human use. However, this vaccine is not licensed and is not commercially available. It has been used experimentally to protect veterinary and laboratory personnel at high risk of exposure to RVF. Other candidate vaccines are under investigation.

RVF virus in host animals

RVF is able to infect many species of animals causing severe disease in domesticated animals including cattle, sheep, camels and goats. Sheep and goats appear to be more susceptible than cattle or camels.

Age has also been shown to be a significant factor in the animal’s susceptibility to the severe form of the disease: over 90% of lambs infected with RVF die, whereas mortality among adult sheep can be as low as 10%.

The rate of abortion among pregnant infected ewes is almost 100%. An outbreak of RVF in animals frequently manifests itself as a wave of unexplained abortions among livestock and may signal the start of an epidemic.

Ecology and mosquito vectors

Several different species of mosquito are able to act as vectors for transmission of the RVF virus. The dominant vector species varies between different regions and different species can play different roles in sustaining the transmission of the virus.

Among animals, the RVF virus is spread primarily by the bite of infected mosquitoes, mainly the Aedes species, which can acquire the virus from feeding on infected animals. The female mosquito is also capable of transmitting the virus directly to her offspring via eggs leading to new generations of infected mosquitoes hatching from eggs.

However, when analysing RVF major outbreaks, 2 ecologically distinct situations should be considered. At primary foci areas, RVF virus persists through transmission between vectors and hosts and maintains through vertical transmission in Aedes mosquitoes. During major outbreak in primary foci, the disease can spread to secondary foci through livestock movement or passive mosquitoes dispersal and amplifies in naïve ruminants via local competent mosquitoes like Culex, Mansonia and Anopheles that act as mechanical vectors. Irrigation schemes, where populations of mosquitoes are abundant during long periods of the year, are highly favourable places for secondary disease transmission.

Prevention and control

Controlling RVF in animals

Outbreaks of RVF in animals can be prevented by a sustained programme of animal vaccination. Both modified live attenuated virus and inactivated virus vaccines have been developed for veterinary use. Only 1 dose of the live vaccine is required to provide long-term immunity but this vaccine may result in spontaneous abortion if given to pregnant animals. The inactivated virus vaccine does not have this side effect, but multiple doses are required in order to provide protection which may prove problematic in endemic areas.

Animal immunization must be implemented prior to an outbreak if an epizootic is to be prevented. Once an outbreak has occurred animal vaccination should NOT be implemented because there is a high risk of intensifying the outbreak. During mass animal vaccination campaigns, animal health workers may, inadvertently, transmit the virus through the use of multi-dose vials and the re-use of needles and syringes. If some of the animals in the herd are already infected and viraemic (although not yet displaying obvious signs of illness), the virus will be transmitted among the herd, and the outbreak will be amplified.

Restricting or banning the movement of livestock may be effective in slowing the expansion of the virus from infected to uninfected areas.

As outbreaks of RVF in animals precede human cases, the establishment of an active animal health surveillance system to detect new cases is essential in providing early warning for veterinary and human public health authorities.

Public health education and risk reduction

During an outbreak of RVF, close contact with animals, particularly with their body fluids, either directly or via aerosols, has been identified as the most significant risk factor for RVF virus infection. Raising awareness of the risk factors of RVF infection as well as the protective measures individuals can take to prevent mosquito bites is the only way to reduce human infection and deaths.

Public health messages for risk reduction should focus on:

- reducing the risk of animal-to-human transmission as a result of unsafe animal husbandry and slaughtering practices. Practicing hand hygiene, wearing gloves and other appropriate individual protective equipment when handling sick animals or their tissues or when slaughtering animals.

- reducing the risk of animal-to-human transmission arising from the unsafe consumption of fresh blood, raw milk or animal tissue. In the epizootic regions, all animal products (blood, meat, and milk) should be thoroughly cooked before eating.

- the importance of personal and community protection against mosquito bites through the use of impregnated mosquito nets, personal insect repellent if available, light coloured clothing (long-sleeved shirts and trousers) and by avoiding outdoor activity at peak biting times of the vector species.

Infection control in health care settings

Although no human-to-human transmission of RVF has been demonstrated, there is still a theoretical risk of transmission of the virus from infected patients to healthcare workers through contact with infected blood or tissues. Healthcare workers caring for patients with suspected or confirmed RVF should implement Standard Precautions when handling specimens from patients.

Standard Precautions define the work practices that are required to ensure a basic level of infection control. Standard Precautions are recommended in the care and treatment of all patients regardless of their perceived or confirmed infectious status. They cover the handling of blood (including dried blood), all other body fluids, secretions and excretions (excluding sweat), regardless of whether they contain visible blood, and contact with non-intact skin and mucous membranes.

As noted above, laboratory workers are also at risk. Samples taken from suspected human and animal cases of RVF for diagnosis should be handled by trained staff and processed in suitably equipped laboratories.

Vector control

Other ways in which to control the spread of RVF involve control of the vector and protection against their bites.

Larviciding measures at mosquito breeding sites are the most effective form of vector control if breeding sites can be clearly identified and are limited in size and extent. During periods of flooding, however, the number and extent of breeding sites is usually too high for larviciding measures to be feasible.

RVF forecasting and climatic models

Forecasting can predict climatic conditions that are frequently associated with an increased risk of outbreaks, and may improve disease control. In Africa, Saudi Arabia and Yemen RVF outbreaks are closely associated with periods of above-average rainfall. The response of vegetation to increased levels of rainfall can be easily measured and monitored by Remote Sensing Satellite Imagery. In addition RVF outbreaks in East Africa are closely associated with the heavy rainfall that occurs during the warm phase of the El Niño–Southern Oscillation (ENSO) phenomenon.

These findings have enabled the successful development of forecasting models and early warning systems for RVF using satellite images and weather/climate forecasting data. Early warning systems, such as these, could be used to trigger detection of animal cases at an early stage of an outbreak, enabling authorities to implement measures to avert impending epidemics.

Within the framework of the new International Health Regulations (2005), the forecasting and early detection of RVF outbreaks, together with a comprehensive assessment of the risk of diffusion to new areas, are essential to enabling the implementation of effective and timely control measures.

WHO response

For the 2016, Niger outbreak, WHO sent a multisectoral national rapid response team, including members from the Ministry of Health, veterinary services and Centre de Recherche Médicale et Sanitaire (CERMES). The unit was deployed for field investigation on 31 August 2016.

In Niger, the WHO Country Office provides technical and financial support for surveillance, outbreak investigation, technical guidelines regarding case definition, case management, shipment of samples, and risk communication.

The Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO), the World Organisation for Animal Health (OIE), and WHO are coordinating on animal and human health and providing additional support to Niger for the outbreak response.

WHO is working with partners in the Global Outbreak Alert and Response Network (GOARN) to coordinate international support for the response. The International Federation of Red Cross and Red Crescent Societies (IFRC) and UNICEF are supporting outbreak response.