Archive for the ‘West Nile Virus’ Category

The World’s Deadliest Animal: Aedes Albopictus Mosquito

Monday, December 16th, 2019The meager, long-legged insect that annoys, bites, and leaves you with an itchy welt is not just a nuisance―it’s one of the world’s most deadly animals. Spreading diseases such as malaria, dengue, West Nile, yellow fever, Zika, chikungunya, and lymphatic filariasis, the mosquito kills more people than any other creature in the world.

In 2018, the number of severe cases of West Nile virus was nearly 25% higher in the Continental U.S. than the average incidence from 2008 to 2017.

In the past 30 years, the worldwide incidence of dengue has risen 30-fold. Forty percent of the world’s population, about 3 billion people, live in areas with a risk of dengue. Dengue is often a leading cause of illness in areas of risk.

Lymphatic filariasis (LF), a parasitic disease transmitted through repeated mosquito bites over a period of months, affects more than 120 million people in 72 countries

In 2017, 435,000 people died from malaria and millions become ill each year including about 2,000 returning travelers in the United States. Nearly half of the world’s population is at risk of this preventable disease.

You can protect yourself from these diseases by avoiding bites from infected mosquitoes.

CDC is committed to providing scientific leadership in fighting these diseases, at home and around the world. From its origins, CDC played a critical role in eliminating malaria from the U.S.

CDC Entomologist, Seth Irish, examines a discarded water bottle for the presence of mosquito larvae, during a training exercise in Dhaka, Bangladesh

Since 2001, global health action has cut the number of malaria deaths in half―saving almost 7 million lives. CDC co-implements the President’s Malaria Initiative in 24 countries and leads Malaria Zero efforts to eliminate malaria from Haiti and efforts to eliminate lymphatic filariasis from Haiti and America Samoa. Haiti is an example of how Mass Drug Administration can reduce spread of LF.

Today, CDC works to eliminate the global burden of malaria and other mosquito-borne diseases. From conducting research to developing tools and approaches to better prevent, detect, and control mosquito-borne diseases, to mitigating drug and insecticide resistance, to accelerating progress towards disease elimination, CDC scientists are working around the world to protect people from mosquito-borne diseases.

August 20: World Mosquito Day

Tuesday, August 20th, 2019Illnesses on the rise from mosquito, tick, and flea bites

Sunday, June 2nd, 2019Almost everyone has been bitten by a mosquito, tick, or flea. These can be vectors for spreading pathogens (germs). A person who gets bitten by a vector and gets sick has a vector-borne disease, like dengue, Zika, Lyme, or plague. Between 2004 and 2016, more than 640,000 cases of these diseases were reported, and 9 new germs spread by bites from infected mosquitoes and ticks were discovered or introduced in the US. State and local health departments and vector control organizations are the nation’s main defense against this increasing threat. Yet, 84% of local vector control organizations lack at least 1 of 5 core vector control competencies. Better control of mosquitoes and ticks is needed to protect people from these costly and deadly diseases.

State and local public health agencies can

- Build and sustain public health programs that test and track germs and the mosquitoes and ticks that spread them.

- Train vector control staff on 5 core competencies for conducting prevention and control activities. http://bit.ly/2FG1OMwExternal

- Educate the public about how to prevent bites and control germs spread by mosquitoes, ticks, and fleas in their communities.

Increasing threat, limited capacity to respond

More cases in the US (2004-2016)

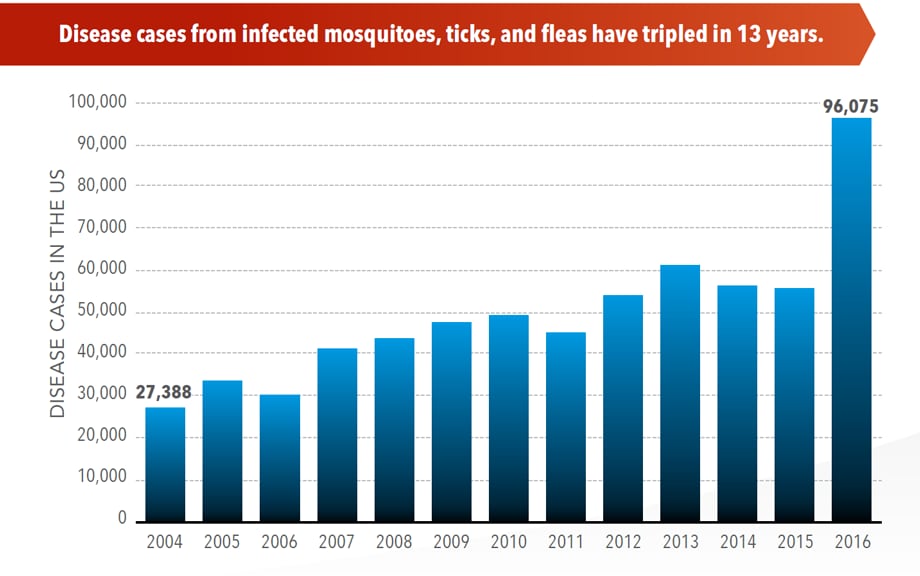

- The number of reported cases of disease from mosquito, tick, and flea bites has more than tripled.

- More than 640,000 cases of these diseases were reported from 2004 to 2016.

- Disease cases from ticks have doubled.

- Mosquito-borne disease epidemics happen more frequently.

More germs (2004-2016)

- Chikungunya and Zika viruses caused outbreaks in the US for the first time.

- Seven new tickborne germs can infect people in the US.

More people at risk

- Commerce moves mosquitoes, ticks, and fleas around the world.

- Infected travelers can introduce and spread germs across the world.

- Mosquitoes and ticks move germs into new areas of the US, causing more people to be at risk.

The US is not fully prepared

-

- Local and state health departments and vector control organizations face increasing demands to respond to these threats.

- More than 80% of vector control organizations report needing improvement in 1 or more of 5 core competencies, such as testing for pesticide resistance.

- More proven and publicly accepted mosquito and tick control methods are needed to prevent and control these diseases.

“Scary Monsters and Nice Sprites” in the fight against Aedes Aegyptii

Friday, April 5th, 2019“…..The observation that such music can delay host attack, reduce blood feeding, and disrupt mating provides new avenues for the development of music-based personal protective and control measures against Aedes-borne diseases…..”

Acta Tropica

Volume 194, June 2019, Pages 93-99

The electronic song “Scary Monsters and Nice Sprites” reduces host attack and mating success in the dengue vector Aedes aegypti

U.S. trends in occurrence of nationally reportable vectorborne diseases during 2004–2016.

Wednesday, May 2nd, 2018Rosenberg R, Lindsey NP, Fischer M, et al. Vital Signs: Trends in Reported Vectorborne Disease Cases — United States and Territories, 2004–2016. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. ePub: 1 May 2018. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.15585/mmwr.mm6717e1.

Key Points

•A total of 642,602 cases of 16 diseases caused by bacteria, viruses, or parasites transmitted through the bites of mosquitoes, ticks, or fleas were reported to CDC during 2004–2016. Indications are that cases were substantially underreported.

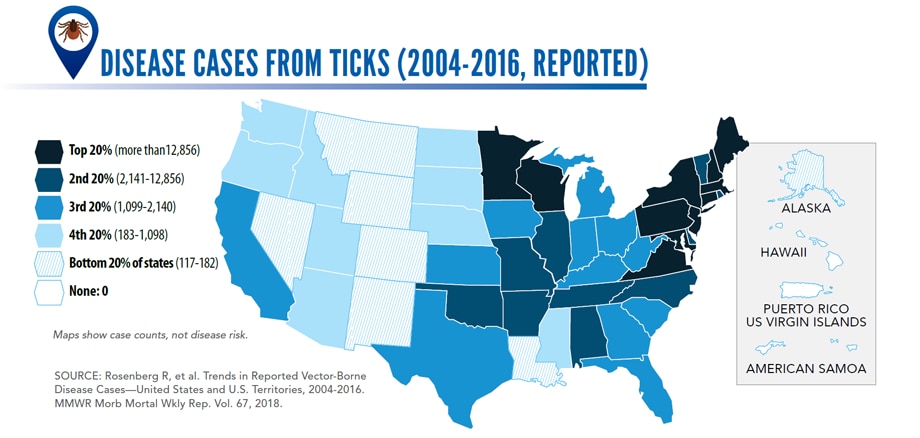

•Tickborne diseases more than doubled in 13 years and were 77% of all vectorborne disease reports. Lyme disease accounted for 82% of all tickborne cases, but spotted fever rickettsioses, babesiosis, and anaplasmosis/ehrlichiosis cases also increased.

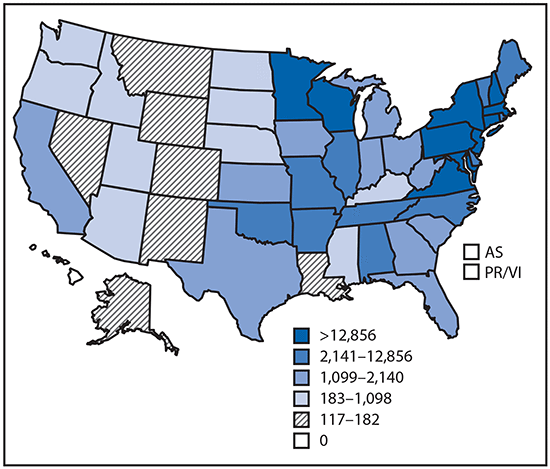

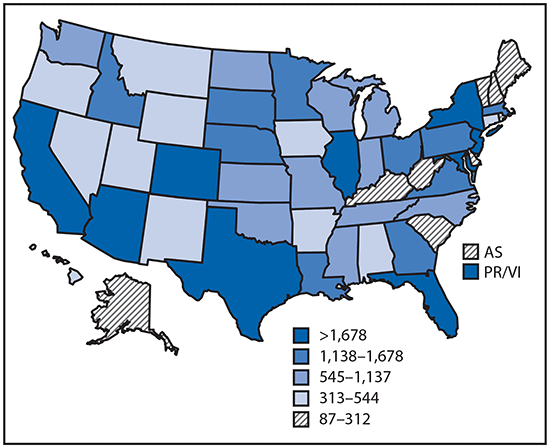

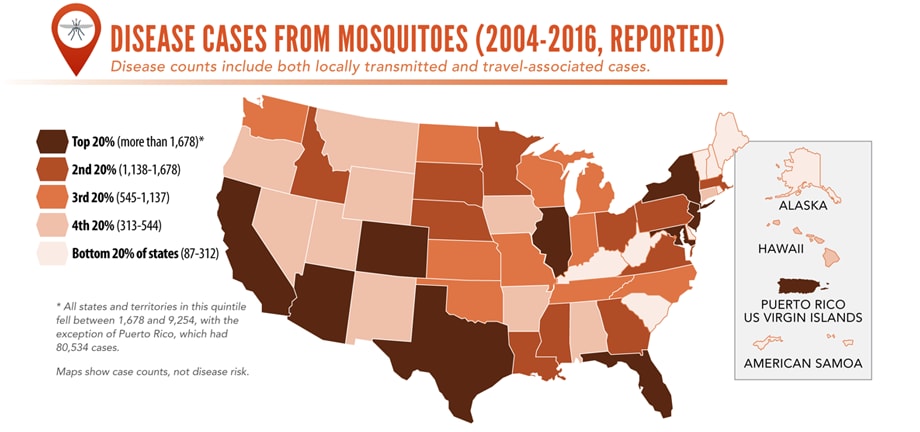

•Tickborne disease cases predominated in the eastern continental United States and areas along the Pacific coast. Mosquitoborne dengue, chikungunya, and Zika viruses were almost exclusively transmitted in Puerto Rico, American Samoa, and the U.S. Virgin Islands, where they were periodically epidemic. West Nile virus, also occasionally epidemic, was widely distributed in the continental United States, where it is the major mosquitoborne disease.

•During 2004–2016, nine vectorborne human diseases were reported for the first time from the United States and U.S. territories. The discovery or introduction of novel vectorborne agents will be a continuing threat.

•Vectorborne diseases have been difficult to prevent and control. A Food and Drug Administration–-approved vaccine is available only for yellow fever virus. Many of the vectorborne diseases, including Lyme disease and West Nile virus, have animal reservoirs. Insecticide resistance is widespread and increasing.

•Preventing and responding to vectorborne disease outbreaks are high priorities for CDC and will require additional capacity at state and local levels for tracking, diagnosing, and reporting cases; controlling vectors; and preventing transmission.

Reported cases* of tickborne disease — U.S. states and territories, 2004–2016

Reported cases* of mosquitoborne disease — U.S. states and territories, 2004–2016

Reported nationally notifiable mosquitoborne,* tickborne, and fleaborne† disease cases — U.S. states and territories, 2004–2016

The number of reported cases of disease from mosquito, tick, and flea bites has more than tripled in the USA (2004-2016)

Wednesday, May 2nd, 2018More cases in the US (2004-2016)

- The number of reported cases of disease from mosquito, tick, and flea bites has more than tripled.

- More than 640,000 cases of these diseases were reported from 2004 to 2016.

- Disease cases from ticks have doubled.

- Mosquito-borne disease epidemics happen more frequently.

More germs (2004-2016)

- Chikungunya and Zika viruses caused outbreaks in the US for the first time.

- Seven new tickborne germs can infect people in the US.

More people at risk

- Commerce moves mosquitoes, ticks, and fleas around the world.

- Infected travelers can introduce and spread germs across the world.

- Mosquitoes and ticks move germs into new areas of the US, causing more people to be at risk.

The US is not fully prepared

- Local and state health departments and vector control organizations face increasing demands to respond to these threats.

- More than 80% of vector control organizations report needing improvement in 1 or more of 5 core competencies, such as testing for pesticide resistance.

- More proven and publicly accepted mosquito and tick control methods are needed to prevent and control these diseases.

Vector-Borne Diseases Reported by States to CDC

Mosquito-borne diseases

- California serogroup viruses

- Chikungunya virus

- Dengue viruses

- Eastern equine encephalitis virus

- Malaria plasmodium

- St. Louis encephalitis virus

- West Nile virus

- Yellow fever virus

- Zika virus

Tickborne diseases

- Anaplasmosis/ehrlichiosis

- Babesiosis

- Lyme disease

- Powassan virus

- Spotted fever rickettsiosis

- Tularemia

Fleaborne disease

- Plague

For more information: https://wwwn.cdc.gov/nndss/

EPA Registers the Wolbachia ZAP Strain in Live Male Asian Tiger Mosquitoes in order to reduce their population thereby reducing the spread numerous diseases of significant human health concern

Thursday, November 9th, 2017

For Release: November 7, 2017

On November 3, 2017, EPA registered a new mosquito biopesticide – ZAP Males® – that can reduce local populations of the type of mosquito (Aedes albopictus, or Asian Tiger Mosquitoes) that can spread numerous diseases of significant human health concern, including the Zika virus.

ZAP Males® are live male mosquitoes that are infected with the ZAP strain, a particular strain of the Wolbachia bacterium. Infected males mate with females, which then produce offspring that do not survive. (Male mosquitoes do not bite people.) With continued releases of the ZAP Males®, local Aedes albopictus populations decrease. Wolbachia are naturally occurring bacteria commonly found in most insect species.

This time-limited registration allows MosquitoMate, Inc. to sell the Wolbachia-infected male mosquitoes for five years in the District of Columbia and the following states: California, Connecticut, Delaware, Illinois, Indiana, Kentucky, Massachusetts, Maine, Maryland, Missouri, New Hampshire, New Jersey, Nevada, New York, Ohio, Pennsylvania, Rhode Island, Tennessee, Vermont, and West Virginia. Before the ZAP Males® can be used in each of those jurisdictions, it must be registered in the state or district.

When the five-year time limit ends, the registration will expire unless the registrant requests further action from EPA.

EPA’s risk assessments, along with the pesticide labeling, EPA’s response to public comments on the Notice of Receipt, and the proposed registration decision, can be found on www.regulations.gov under docket number EPA-HQ-OPP-2016-0205.

CDC recommendations to healthcare providers treating patients in Puerto Rico and USVI, as well as those treating patients in the continental US who recently traveled in hurricane-affected areas during the period of September 2017 – March 2018.

Wednesday, October 25th, 2017Advice for Providers Treating Patients in or Recently Returned from Hurricane-Affected Areas, Including Puerto Rico and US Virgin Islands

Distributed via the CDC Health Alert Network

October 24, 2017, 1330 ET (1:30 PM ET)

CDCHAN-00408

Summary

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) is working with federal, state, territorial, and local agencies and global health partners in response to recent hurricanes. CDC is aware of media reports and anecdotal accounts of various infectious diseases in hurricane-affected areas, including Puerto Rico and the US Virgin Islands (USVI). Because of compromised drinking water and decreased access to safe water, food, and shelter, the conditions for outbreaks of infectious diseases exist.

The purpose of this HAN advisory is to remind clinicians assessing patients currently in or recently returned from hurricane-affected areas to be vigilant in looking for certain infectious diseases, including leptospirosis, dengue, hepatitis A, typhoid fever, vibriosis, and influenza. Additionally, this Advisory provides guidance to state and territorial health departments on enhanced disease reporting.

Background

Hurricanes Irma and Maria made landfall in Puerto Rico and USVI in September 2017, causing widespread flooding and devastation. Natural hazards associated with the storms continue to affect many areas. Infectious disease outbreaks of diarrheal and respiratory illnesses can occur when access to safe water and sewage systems are disrupted and personal hygiene is difficult to maintain. Additionally, vector borne diseases can occur due to increased mosquito breeding in standing water; both Puerto Rico and USVI are at risk for outbreaks of dengue, Zika, and chikungunya.

Health care providers and public health practitioners should be aware that post-hurricane environmental conditions may pose an increased risk for the spread of infectious diseases among patients in or recently returned from hurricane-affected areas; including leptospirosis, dengue, hepatitis A, typhoid fever, vibriosis, and influenza. The period of heightened risk may last through March 2018, based on current predictions of full restoration of power and safe water systems in Puerto Rico and USVI.

In addition, providers in health care facilities that have experienced water damage or contaminated water systems should be aware of the potential for increased risk of infections in those facilities due to invasive fungi, nontuberculous Mycobacterium species, Legionella species, and other Gram-negative bacteria associated with water (e.g., Pseudomonas), especially among critically ill or immunocompromised patients.

Cholera has not occurred in Puerto Rico or USVI in many decades and is not expected to occur post-hurricane.

Recommendations

These recommendations apply to healthcare providers treating patients in Puerto Rico and USVI, as well as those treating patients in the continental US who recently traveled in hurricane-affected areas (e.g., within the past 4 weeks), during the period of September 2017 – March 2018.

- Health care providers and public health practitioners in hurricane-affected areas should look for community and healthcare-associated infectious diseases.

- Health care providers in the continental US are encouraged to ask patients about recent travel (e.g., within the past 4 weeks) to hurricane-affected areas.

- All healthcare providers should consider less common infectious disease etiologies in patients presenting with evidence of acute respiratory illness, gastroenteritis, renal or hepatic failure, wound infection, or other febrile illness. Some particularly important infectious diseases to consider include leptospirosis, dengue, hepatitis A, typhoid fever, vibriosis, and influenza.

- In the context of limited laboratory resources in hurricane-affected areas, health care providers should contact their territorial or state health department if they need assistance with ordering specific diagnostic tests.

- For certain conditions, such as leptospirosis, empiric therapy should be considered pending results of diagnostic tests— treatment for leptospirosis is most effective when initiated early in the disease process. Providers can contact their territorial or state health department or CDC for consultation.

- Local health care providers are strongly encouraged to report patients for whom there is a high level of suspicion for leptospirosis, dengue, hepatitis A, typhoid, and vibriosis to their local health authorities, while awaiting laboratory confirmation.

- Confirmed cases of leptospirosis, dengue, hepatitis A, typhoid fever, and vibriosis should be immediately reported to the territorial or state health department to facilitate public health investigation and, as appropriate, mitigate the risk of local transmission. While some of these conditions are not listed as reportable conditions in all states, they are conditions of public health importance and should be reported.

For More Information

- General health information about hurricanes and other tropical storms: https://www.cdc.gov/disasters/hurricanes/index.html

- Information about Hurricane Maria: https://www.cdc.gov/disasters/hurricanes/hurricane_maria.html

- Information for Travelers:

- Travel notice for Hurricanes Irma and Maria in the Caribbean: https://wwwnc.cdc.gov/travel/notices/alert/hurricane-irma-in-the-caribbean

- Health advice for travelers to Puerto Rico: https://wwwnc.cdc.gov/travel/destinations/traveler/none/puerto-rico?s_cid=ncezid-dgmq-travel-single-001

- Health advice for travelers to the U.S. Virgin Islands: https://wwwnc.cdc.gov/travel/destinations/traveler/none/usvirgin-islands?s_cid=ncezid-dgmq-travel-leftnav-traveler

- Resources from CDC Health Information for International Travel 2018 (the Yellow Book):

- Post-travel Evaluation: https://wwwnc.cdc.gov/travel/yellowbook/2018/post-travel-evaluation/general-approach-to-the-returned-traveler

- Information about infectious diseases after a disaster: https://www.cdc.gov/disasters/disease/infectious.html

- Dengue: https://www.cdc.gov/dengue/index.html

- Hepatitis A: https://www.cdc.gov/hepatitis/HAV/index.htm

- Leptospirosis: https://www.cdc.gov/leptospirosis/

- Typhoid fever: https://www.cdc.gov/typhoid-fever/index.html

- Vibriosis: https://www.cdc.gov/vibrio/index.html

- Information about other infectious diseases of concern:

- Conjunctivitis: https://www.cdc.gov/conjunctivitis/

- Influenza: https://www.cdc.gov/flu/index.htm

- Scabies: https://www.cdc.gov/parasites/scabies/index.html

- Tetanus and wound management: https://www.cdc.gov/disasters/emergwoundhcp.html

- Tetanus in Areas Affected by a Hurricane: Guidelines for Clinicians https://emergency.cdc.gov/coca/cocanow/2017/2017sept12.asp

Disease-carrying mosquitoes may be moving into new ecological niches with greater frequency.

Friday, September 8th, 2017“…..The website, ProMED mail, has carried more than a dozen such reports since June, all involving mosquito species known to transmit human diseases.

Most reports have concerned the United States, where, for example, Aedes aegypti — the yellow fever mosquito, which also spreads Zika, dengue and chikungunya — has been turning up in counties in California and Nevada where it had never, or only rarely, been seen.

Other reports have noted mosquito species found for the first time on certain South Pacific islands, or in parts of Europe where harsh winters previously kept them at bay…..”

Fatal Case of West Nile Neuroinvasive Disease in Bulgaria

Tuesday, November 22nd, 2016“….A 69-year-old man was admitted to the Emergency Center, Military Medical Academy (Sofia, Bulgaria), on August 27, 2015, because of fever, headache, hand tremor, muscle weakness and disability of lower extremities, nausea, and vomiting. These signs and symptoms developed 3 days before hospitalization. The patient reported being bitten by insects through the summer. He also had concomitant cardiovascular disease. In the 24-hour period after hospitalization, a consciousness disorder and deterioration of the extremities’ weakness developed, and the patient had a Glasgow come score <8.

The patient was transferred to Department of Intensive Care. Neurologic examination showed neck stiffness, positive bilateral symptoms of Kernig and Brudzinski, right facial paralysis, and areflexia of the lower extremities. The patient underwent intubation, and despite complex medical therapy, a cardiopulmonary disorder developed, and he died 14 days after admission.

Laboratory test results at admission were within reference ranges. Lumbar puncture was performed, and cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) testing showed a clear color, leukocytes 39 ×106 cells/L (reference range 0–5 ×106 cells/L), polymorphonucleocytes 2% (0%–6%), lymphocytes 93% (40%–80%), monocytes 5% (15%–45%), protein 0.57 g/L (0.2–0.45 g/L), glucose 4.3 mmol/L (2.2–3.9 mmol/L), and chloride 127.9 mmol/L (98–106 mmol/L)….”

Microbiological investigations of blood, CSF, urine, and throat swab specimens showed no bacterial growth. Immunoserologic test results for neurotropic infectious and parasitologic agents were negative, except for a positive result for IgM against WNV.