Archive for the ‘Zika virus’ Category

CDC: Pregnant Women with Any Laboratory Evidence of Possible Zika Virus Infection in the United States and Territories, 2016

Friday, June 17th, 2016Pregnant Women with Any Laboratory Evidence of Possible Zika Virus Infection

US States and the District of Columbia*: 234

*Includes aggregated data reported to the US Zika Pregnancy Registry as of June 9, 2016

US Territories**: 189

**Includes aggregated data from the US territories reported to the US Zika Pregnancy Registry and data from Puerto Rico reported to the Zika Active Pregnancy Surveillance System as of June 9, 2016

What these updated numbers show

- These updated numbers reflect counts of pregnant women in the United States with any laboratory evidence of possible Zika virus infection, with or without symptoms. Pregnant women with laboratory evidence include those in whom viral particles have been detected and those with evidence of an immune reaction to a recent virus that is likely to be Zika.

- This information will help healthcare providers as they counsel pregnant women affected by Zika and is essential for planning at the federal, state, and local levels for clinical, public health, and other services needed to support pregnant women and families affected by Zika.

What these new numbers do not show

- These new numbers are not comparable to the previous reports. These updated numbers reflect a different, broader population of pregnant women.

- These updated numbers are not real time estimates. They will reflect the number of pregnant women reported with any laboratory evidence of possible Zika virus infection as of 12 noon every Thursday the week prior; numbers will be delayed one week.

Where do these numbers come from?

These data reflect pregnant women in the US Zika Pregnancy Registry and the Zika Active Pregnancy Surveillance System in Puerto Rico. CDC, in collaboration with state, local, tribal and territorial health departments, established these registries for comprehensive monitoring of pregnancy and infant outcomes following Zika virus infection.

The data collected through these registries will be used to update recommendations for clinical care, to plan for services and support for pregnant women and families affected by Zika virus, and to improve prevention of Zika virus infection during pregnancy.

What are the outcomes for these pregnancies?

Visit CDC’s webpage for updated counts of poor pregnancy outcomes related to Zika. Most of the pregnancies monitored by these systems are ongoing. CDC will not report outcomes until pregnancies are complete.

CDC: Outcomes of Pregnancies with Laboratory Evidence of Possible Zika Virus Infection in the United States, 2016

Friday, June 17th, 2016Outcomes of Pregnancies with Laboratory Evidence of Possible Zika Virus Infection in the United States, 2016

Liveborn infants with birth defects*: 3

Includes aggregated data reported to the US Zika Pregnancy Registry as of June 9, 2016

Pregnancy losses with birth defects**: 3

Includes aggregated data reported to the US Zika Pregnancy Registry as of June 9, 2016

What these numbers show

- These numbers reflect poor outcomes among pregnancies with laboratory evidence of possible Zika virus infection reported to the US Zika Pregnancy Registry.

- The number of live-born infants and pregnancy losses with birth defects are combined for the 50 US states and the District of Columbia. To protect the privacy of the women and children affected by Zika, CDC is not reporting individual state, tribal, territorial or jurisdictional level data.

- The poor birth outcomes reported include those that have been detected in infants infected with Zika before or during birth, including microcephaly, calcium deposits in the brain indicating possible brain damage, excess fluid in the brain cavities and surrounding the brain, absent or poorly formed brain structures, abnormal eye development, or other problems resulting from damage to brain that affects nerves, muscles and bones, such as clubfoot or inflexible joints.

What these new numbers do not show

- These numbers are not real time estimates. They will reflect the outcomes of pregnancies reported with any laboratory evidence of possible Zika virus infection as of 12 noon every Thursday the week prior; numbers will be delayed one week.

- These numbers do not reflect outcomes among ongoing pregnancies.

- Although these outcomes occurred in pregnancies with laboratory evidence of Zika virus infection, we do not know whether they were caused by Zika virus infection or other factors.

Where do these numbers come from?

- These data reflect pregnancies reported to the US Zika Pregnancy Registry. CDC, in collaboration with state, local, tribal and territorial health departments, established this registry for comprehensive monitoring of pregnancy and infant outcomes following Zika virus infection.

- The data collected through this system will be used to update recommendations for clinical care, to plan for services and support for pregnant women and families affected by Zika virus, and to improve prevention of Zika virus infection during pregnancy.

* Includes microcephaly, calcium deposits in the brain indicating possible brain damage, excess fluid in the brain cavities and surrounding the brain, absent or poorly formed brain structures, abnormal eye development, or other problems resulting from damage to brain that affects nerves, muscles and bones, such as clubfoot or inflexible joints.

**Includes miscarriage, stillbirths, and terminations with evidence of the birth defects mentioned above

CDC’s Interim Zika Response Plan

Wednesday, June 15th, 2016The 57-page plan: http://files.ctctcdn.com/6f0559fe101/01ee9685-9672-4d5c-88e5-0873b30c950f.pdf

CDC will support and help states with key tasks at different stages of the outbreak

Phase level 0 —signifying preparedness activity for when the vector is present or possible in the state—to level 4, when widespread local Zika infections are occurring is several jurisdictions within a state. Most states are currently in phase 0 or 1, meaning Aedes mosquitoes are biting and travel-related or sexually transmitted cases have occurred.

Phase 2 would be a single locally acquired case or a case cluster in a single household.

Phase 3 consists of widespread local transmission contained to a 1-mile area

Phase 4 is widespread transmission in multiple locations.

The 3rd meeting of the International Health Regulations (2005) (IHR(2005)) Emergency Committee on Zika virus

Wednesday, June 15th, 2016WHO statement on the third meeting of the International Health Regulations (2005) (IHR(2005)) Emergency Committee on Zika virus and observed increase in neurological disorders and neonatal malformations

The third meeting of the Emergency Committee (EC) convened by the Director-General under the International Health Regulations (2005) (IHR 2005) regarding microcephaly, other neurological disorders and Zika virus was held by teleconference on 14 June 2016, from 13:00 to 17:15 Central European Time. In addition to providing views to the Director-General on whether the event continued to constitute a Public Health Emergency of International Concern (PHEIC), the Committee was asked to consider the potential risks of Zika transmission for mass gatherings, including the Olympic and Paralympic Games scheduled for August and September 2016, respectively, in Rio de Janeiro, Brazil.

The Committee was briefed on the implementation of the Temporary Recommendations issued by the Director-General on 8 March 2016 and updated on the epidemiology and association of Zika virus infection, microcephaly and Guillain-Barré Syndrome (GBS) since that time. The following States Parties provided information on microcephaly, GBS and other neurological disorders occurring in the presence of Zika virus transmission: Brazil, Cabo Verde, Colombia, France, and the United States of America. Advisors to the Committee provided further information on the potential risks of Zika virus transmission associated with mass gatherings and the upcoming Olympic and Paralympic Games, and the Committee thoroughly reviewed the range of public perspectives, opinions and concerns that have recently been aired on this subject.

The Committee concurred with the international scientific consensus, reached since the Committee last met, that Zika virus is a cause of microcephaly and GBS, and, consequently, that Zika virus infection and its associated congenital and other neurological disorders is a Public Health Emergency of International Concern (PHEIC). The Committee restated the advice it provided to the Director-General in its 2nd meeting in the areas of public health research on microcephaly, other neurological disorders and Zika virus, surveillance, vector control, risk communications, clinical care, travel measures, and research and product development.

The Committee noted that mass gatherings, such as the Olympic and Paralympic Games, can bring together substantial numbers of susceptible individuals, and can pose a risk to the individuals themselves, can result in the amplification of transmission and can, potentially, contribute to the international spread of a communicable disease depending on its epidemiology, the risk factors present and the mitigation strategies that are in place. In the context of Zika virus, the Committee noted that the individual risks in areas of transmission are the same whether or not a mass gathering is conducted, and can be minimized by good public health measures. The Committee reaffirmed and updated its advice to the Director-General on the prevention of infection in international travellers as follows:

- Pregnant women should be advised not to travel to areas of ongoing Zika virus outbreaks; pregnant women whose sexual partners live in or travel to areas with Zika virus outbreaks should ensure safe sexual practices or abstain from sex for the duration of their pregnancy,

- Travellers to areas with Zika virus outbreaks should be provided with up to date advice on potential risks and appropriate measures to reduce the possibility of exposure through mosquito bites and sexual transmission and, upon return, should take appropriate measures, including practicing safer sex, to reduce the risk of onward transmission,

- The World Health Organization should regularly update its guidance on travel with evolving information on the nature and duration of risks associated with Zika virus infection.

Based on the existing evidence from the current Zika virus outbreak, it is known that this virus can spread internationally and establish new transmission chains in areas where the vector is present. Focusing on the potential risks associated with the Olympic and Paralympic Games, the Committee reviewed information provided by Brazil and Advisors specializing in arboviruses, the international spread of infectious diseases, travel medicine, mass gatherings and bioethics. The Committee concluded that there is a very low risk of further international spread of Zika virus as a result of the Olympic and Paralympic Games as Brazil will be hosting the Games during the Brazilian winter when the intensity of autochthonous transmission of arboviruses, such as dengue and Zika viruses, will be minimal and is intensifying vector-control measures in and around the venues for the Games which should further reduce the risk of transmission.

The Committee reaffirmed its previous advice that there should be no general restrictions on travel and trade with countries, areas and/or territories with Zika virus transmission, including the cities in Brazil that will be hosting the Olympic and Paralympic Games. The Committee provided additional advice to the Director-General on mass gatherings and the Olympic and Paralympic Games as follows:

- Countries, communities and organizations that are convening mass gatherings in areas affected by Zika virus outbreaks should undertake a risk assessment prior to the event and increase measures to reduce the risk of exposure to Zika virus,

- Brazil should continue its work to intensify vector control measures in and around the cities and venues hosting Olympic and Paralympic Games events, make the nature and impact of those measures publicly available, enhance surveillance for Zika virus circulation and the mosquito vector in the cities hosting the events and publish that information in a timely manner, and ensure the availability of sufficient insect repellent and condoms for athletes and visitors,

- Countries with travellers to and from the Olympic and Paralympic Games should ensure that those travellers are fully informed on the risks of Zika virus infection, the personal protective measures that should be taken to reduce those risks, and the action that they should take if they suspect they have been infected. Countries should also establish protocols for managing returning travellers with Zika virus infection based on WHO guidance,

- Countries should act in accordance with guidance from the World Health Organization on mass gatherings in the context of Zika virus outbreaks, which will be updated as further information becomes available on the risks associated with Zika virus infection and factors affecting national and international spread.

Based on this advice the Director-General declared the continuation of the Public Health Emergency of International Concern (PHEIC). The Director-General reissued the Temporary Recommendations from the 2nd meeting of the Committee, endorsed the additional advice from the Committee’s 3rd meeting, and issued them as Temporary Recommendations under the IHR (2005). The Director-General thanked the Committee Members and Advisors for their advice.

Pregnant Women with Any Laboratory Evidence of Possible Zika Virus Infection in the United States and Territories, 2016

Saturday, June 4th, 2016Pregnant Women with Any Laboratory Evidence of Possible Zika Virus Infection

US States and the District of Columbia

- Pregnant women with any laboratory evidence of possible Zika virus infection: 195*

*This update includes aggregated data reported to the US Zika Pregnancy Registry as of May 26, 2016.

US Territories

- Pregnant women with any laboratory evidence of possible Zika virus infection: 146*

*This update includes data from the US territories reported to the US Zika Pregnancy Registry and data from Puerto Rico reported to the Zika Active Pregnancy Surveillance System as of May 26, 2016.

About These Numbers

What these updated numbers show

- These updated numbers reflect counts of pregnant women in the United States with any laboratory evidence of possible Zika virus infection, with or without symptoms. Pregnant women with laboratory evidence include those in whom viral particles have been detected and those with evidence of an immune reaction to a recent virus that is likely to be Zika.

- This information will help healthcare providers as they counsel pregnant women affected by Zika and is essential for planning at the federal, state, and local levels for clinical, public health, and other services needed to support pregnant women and families affected by Zika.

What these new numbers do not show

- These new numbers are not comparable to the previous reports. These updated numbers reflect a different, broader population of pregnant women.

- These updated numbers are not real time estimates. They will reflect the number of pregnant women reported with any laboratory evidence of possible Zika virus infection as of 12 noon every Thursday the week prior; numbers will be delayed one week.

Where do these numbers come from?

These data reflect pregnant women in the US Zika Pregnancy Registry and the Zika Active Pregnancy Surveillance System in Puerto Rico. CDC, in collaboration with state, local, tribal and territorial health departments, established these registries for comprehensive monitoring of pregnancy and infant outcomes following Zika virus infection.

The data collected through these registries will be used to update recommendations for clinical care, to plan for services and support for pregnant women and families affected by Zika virus, and to improve prevention of Zika virus infection during pregnancy.

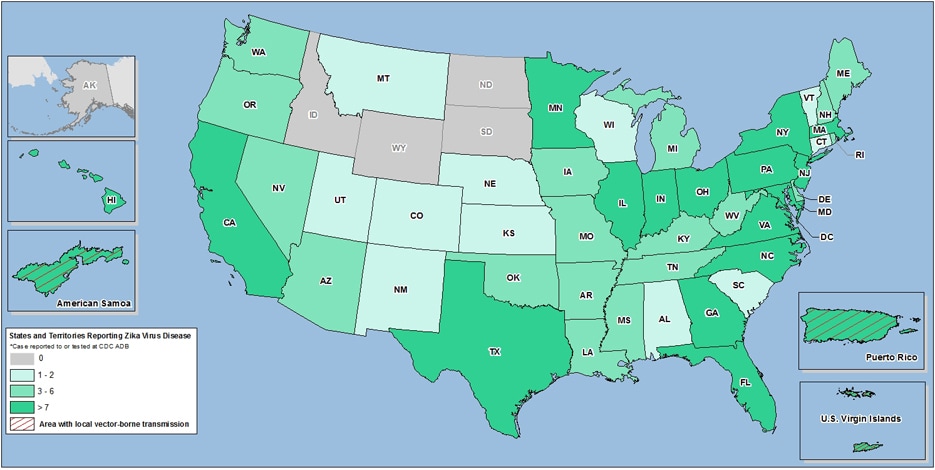

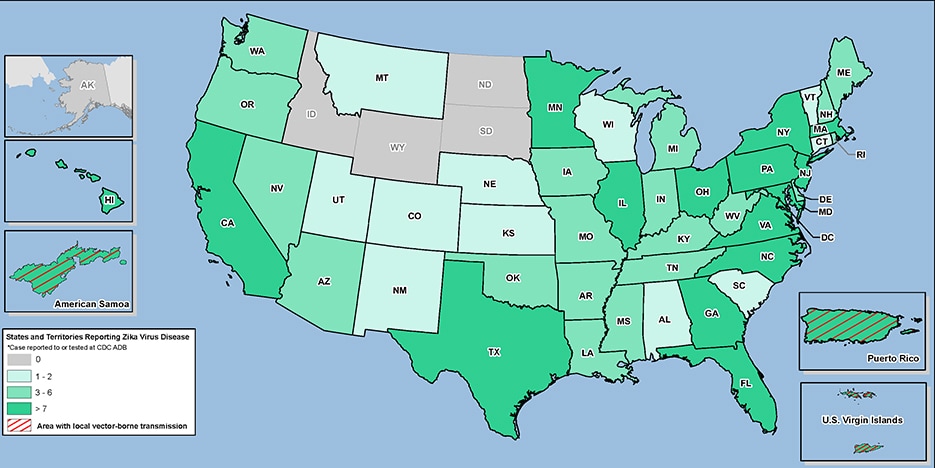

Zika virus disease in the United States, 2015–2016

Saturday, June 4th, 2016As of June 01, 2016 (5 am EST)

- Zika virus disease and Zika virus congenital infection are nationally notifiable conditions.

- This update from the CDC Arboviral Disease Branch includes provisional data reported to ArboNET for January 01, 2015 – June 01, 2016.

US States

- Travel-associated cases reported: 618

- Locally acquired vector-borne cases reported: 0

- Total: 618

- Sexually transmitted: 11

- Guillain-Barré syndrome: 1

US Territories

- Travel-associated cases reported: 4

- Locally acquired cases reported: 1,110

- Total: 1,114

- Guillain-Barré syndrome: 8

Laboratory-confirmed Zika virus disease cases reported to ArboNET by state or territory — United States, 2015–2016 (as of June 01, 2016)

WHO tries to define the syndrome associated with congenital Zika virus infection

Saturday, June 4th, 2016WHO

Defining the syndrome associated with congenital Zika virus infection

Anthony Costello a, Tarun Dua b, Pablo Duran c, Metin Gülmezoglu d, Olufemi T Oladapo d, William Perea e, João Pires f, Pilar Ramon-Pardo g, Nigel Rollins a & Shekhar Saxena b

a. Department of Maternal, Newborn, Child and Adolescent Health, World Health Organization, Geneva, Switzerland.

b. Department of Mental Health and Substance Abuse, World Health Organization, 20 Avenue Appia, 1211 Geneva 27, Switzerland.

c. Center For Perinatology, Women and Reproductive Health, Pan American Health Organization/World Health Organization, Montevideo, Uruguay.

d. Department of Reproductive Health and Research, World Health Organization, Geneva, Switzerland.

e. Department of Pandemic and Epidemic Diseases, World Health Organization, Geneva, Switzerland.

f. Division of Communicable Diseases and Health Security, World Health Organization Regional Office for Europe, Copenhagen, Denmark.

g. Department of Communicable Diseases and Health Analysis, Pan American Health Organization/ World Health Organization, Washington, USA.

Correspondence to Tarun Dua (email: duat@who.int).

Bulletin of the World Health Organization 2016;94:406-406A. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.2471/BLT.16.176990

Zika virus infection in humans is usually mild or asymptomatic. However, some babies born to women infected with Zika virus have severe neurological sequelae. An unusual cluster of cases of congenital microcephaly and other neurological disorders in the WHO Region of the Americas, led to the declaration of a public health emergency of international concern by the World Health Organization (WHO) on 1 February 2016. By 5 May 2016, reports of newborns or fetuses with microcephaly or other malformations – presumably associated with Zika virus infection – have been described in the following countries and territories: Brazil (1271 cases); Cabo Verde (3 cases); Colombia (7 cases); French Polynesia (8 cases); Martinique (2 cases) and Panama (4 cases). Additional cases were also reported in Slovenia and the United States of America, in which the mothers had histories of travel to Brazil during their pregnancies.1

Zika virus is an intensely neurotropic virus that particularly targets neural progenitor cells but also – to a lesser extent – neuronal cells in all stages of maturity.

Viral cerebritis can disrupt cerebral embryogenesis and result in microcephaly and other neurological abnormalities.2 Zika virus has been isolated from the brains and cerebrospinal fluid of neonates born with congenital microcephaly and identified in the placental tissue of mothers who had had clinical symptoms consistent with Zika virus infection during their pregnancies.3–5 The spatiotemporal association of cases of microcephaly with the Zika virus outbreak and the evidence emerging from case reports and epidemiologic studies, has led to a strong scientific consensus that Zika virus is implicated in congenital abnormalities.6,7

Existing evidence and unpublished data shared with WHO highlight the wider range of congenital abnormalities probably associated with the acquisition of Zika virus infection in utero. In addition to microcephaly, other manifestations include craniofacial disproportion, spasticity, seizures, irritability and brainstem dysfunction including feeding difficulties, ocular abnormalities and findings on neuroimaging such as calcifications, cortical disorders and ventriculomegaly.3–6,8–10 Similar to other infections acquired in utero, cases range in severity; some babies have been reported to have neurological abnormalities with a normal head circumference.

Preliminary data from Colombia and Panama also suggest that the genitourinary, cardiac and digestive systems can be affected (Pilar Ramon-Pardo, unpublished data).

The range of abnormalities seen and the likely causal relationship with Zika virus infection suggest the presence of a new congenital syndrome.

WHO has set in place a process for defining the spectrum of this syndrome. The process focuses on mapping and analysing the clinical manifestations encompassing the neurological, hearing, visual and other abnormalities, and neuroimaging findings. WHO will need good antenatal and postnatal histories and follow-up data, sound laboratory results, exclusion of other etiologies and analysis of imaging findings to properly delineate this syndrome. The scope of the syndrome will expand as further information and longer follow-up of affected children become available. The surveillance system that was established as part of the epidemic response to the outbreak initially called only for the reporting of microcephaly cases. This surveillance guidance has been expanded to include a spectrum of congenital malformations that could be associated with intrauterine Zika virus infection.11

Effective sharing of data is needed to define this syndrome. A few reports have described a wide range of abnormalities,3–6,8–10 but most data related to congenital manifestations of Zika infection remain unpublished. Global health organizations and research funders have committed to sharing data and results relevant to the Zika epidemic as openly as possible.12 Further analysis of data from cohorts of pregnant women with Zika virus infection are needed to understand all outcomes of Zika virus infection in pregnancy.

Thirty-seven countries and territories in the Region of the Americas now report mosquito-borne transmission of Zika virus and risk of sexual transmission. With such spread, it is possible that many thousands of infants will incur moderate to severe neurological disabilities. Therefore, routine surveillance systems and research protocols need to include a larger population than simply children with microcephaly. The health system response, including psychosocial services for women, babies and affected families will need to be fully resourced.

The Zika virus public health emergency is distinct because of its long-term health consequences and social impact. A coordinated approach to data sharing, surveillance and research is needed. WHO has thus started coordinating efforts to define the congenital Zika virus syndrome and issues an open invitation to all partners to join in this effort.

Acknowledgements

We thank the guideline development group members for the management of Zika virus associated complications, including Melania Amorim, Adriana Melo, Marianne Besnard, Jose Guilherme Cecatti, Gustavo Malinger and Vanessa van Der Linden who shared their unpublished data during the meeting.

References

- Zika situation report (5 May 2016). Geneva: World Health Organization; 2016. Available from: http://www.who.int/emergencies/zika-virus/situation-report/5-may-2016/en/ [cited 2016 May 10].

- Tang H, Hammack C, Ogden SC, Wen Z, Qian X, Li Y, et al. Zika virus infects human cortical neural progenitors and attenuates their growth. Cell Stem Cell. 2016 May 5;18(5):587–90. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.stem.2016.02.016 pmid: 26952870

- Driggers RW, Ho CY, Korhonen EM, Kuivanen S, Jääskeläinen AJ, Smura T, et al. Zika virus infection with prolonged maternal viremia and fetal brain abnormalities. N Engl J Med. 2016 Mar 30;NEJMoa1601824. http://dx.doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa1601824 pmid: 27028667

- Brasil P, Pereira JP Jr, Raja Gabaglia C, Damasceno L, Wakimoto M, Ribeiro Nogueira RM, et al. Zika virus infection in pregnant women in Rio de Janeiro – preliminary report. N Engl J Med. 2016 Mar 4;NEJMoa1602412. http://dx.doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa1602412 pmid: 26943629

- Mlakar J, Korva M, Tul N, Popović M, Poljšak-Prijatelj M, Mraz J, et al. Zika virus associated with microcephaly. N Engl J Med. 2016 Mar 10;374(10):951–8. http://dx.doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa1600651 pmid: 26862926

- Cauchemez S, Besnard M, Bompard P, Dub T, Guillemette-Artur P, Eyrolle-Guignot D, et al. Association between Zika virus and microcephaly in French Polynesia, 2013-15: a retrospective study. Lancet. 2016 Mar 15;S0140-6736(16)00651-6. pmid: 26993883

- SA Rasmussen, Jamieson DJ, Honein MA, Petersen LR. Zika virus and birth defects – reviewing the evidence for causality. N Engl J Med. 2016 Apr 13.

- Besnard M, Eyrolle-Guignot D, Guillemette-Artur P, Lastère S, Bost-Bezeaud F, Marcelis L, et al. Congenital cerebral malformations and dysfunction in fetuses and newborns following the 2013 to 2014 Zika virus epidemic in French Polynesia. Euro Surveill. 2016 Mar 31;21(13):30181. http://dx.doi.org/10.2807/1560-7917.ES.2016.21.13.30181 pmid: 27063794

- de Paula Freitas B, de Oliveira Dias JR, Prazeres J, Sacramento GA, Ko AI, Maia M, et al. Ocular findings in infants with microcephaly associated with presumed Zika virus congenital infection in Salvador, Brazil. JAMA Ophthalmol. 2016 Feb 9; http://dx.doi.org/10.1001/jamaophthalmol.2016.0267 pmid: 26865554

- Miranda-Filho DB, Martelli CM, Ximenes RA, Araújo TV, Rocha MA, Ramos RC, et al. Initial Description of the presumed congenital Zika syndrome. Am J Public Health. 2016 Apr;106(4):598–600. http://dx.doi.org/10.2105/AJPH.2016.303115 pmid: 26959258

- Case definitions. Washington: Regional Office in the Americas/World Health Organization; 2016. Available from: http://www.paho.org/hq/index.php?option=com_content&view=article&id=11117&Itemid=41532&lang=en [cited 2016 May 10].

- Dye C, Bartolomeos K, Moorthy V, Kieny MP. Data sharing in public health emergencies: a call to researchers. Bull World Health Organ. 2016 Mar 1;94(3):158. http://dx.doi.org/10.2471/BLT.16.170860 pmid: 26966322

NYC combats Zika

Monday, May 30th, 2016

CDC: Zika virus disease in the United States, 2015–2016

Monday, May 30th, 2016Zika virus disease in the United States, 2015–2016

As of May 25, 2016 (5 am EST)

- Zika virus disease and Zika virus congenital infection are nationally notifiable conditions.

- This update from the CDC Arboviral Disease Branch includes provisional data reported to ArboNET for January 1, 2015 – May 25, 2016.

US States

- Travel-associated cases reported: 591

- Locally acquired vector-borne cases reported: 0

- Total: 591

- Sexually transmitted: 11

- Guillain-Barré syndrome: 1

US Territories

- Travel-associated cases reported: 4

- Locally acquired cases reported: 935

- Total: 939

- Guillain-Barré syndrome: 5

Laboratory-confirmed Zika virus disease cases reported to ArboNET by state or territory — United States, 2015–2016 (as of May 25, 2016)