Archive for the ‘Zika virus’ Category

Zika Virus: ‘… “What we’re seeing are the consequences of this virus turning from the African strain to a pandemic strain,” said Dr. Peter Hotez, dean of the National School of Tropical Medicine at Baylor College of Medicine…’

Wednesday, April 6th, 2016

“…..Top Zika investigators now believe that the birth defect microcephaly and the paralyzing Guillain-Barre syndrome may be just the most obvious maladies caused by the mosquito-borne virus……Guillain-Barre is an autoimmune disorder, in which the body attacks itself in the aftermath of an infection. But the newly discovered brain and spinal cord infections are known to be caused by a different mechanism – a direct attack on nerve cells……

Mosquitoes have infected 2 women with the Zika virus in Vietnam

Tuesday, April 5th, 2016A 64-year-old woman in the beach city of Nha Trang

A pregnant 33-year-old in Ho Chi Minh City

** Zika Action Plan Summit: CDC

Saturday, April 2nd, 2016National Zika Summit Focused on Coordinated U.S. Response

Officials from most-at-risk states in Atlanta to develop action plans for implementation following Summit

Today, more than 300 local, state, and federal government officials; health experts; and non-government partners are gathering at the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) to prepare for the likelihood of mosquito-borne transmission of the Zika virus in some parts of the continental United States. The Commonwealth of Puerto Rico, U.S. Virgin Islands, and American Samoa already are experiencing active Zika transmission.

Hosted by CDC, the one-day Zika Action Plan Summit brings together officials from local, state and federal jurisdictions, as well as non-government organizations, to help ensure a coordinated response to the mosquito-borne illness linked to the devastating birth defect microcephaly. The summit aims to identify gaps in readiness and provide technical support to states in the development of Zika action plans that will allow their jurisdictions to effectively prepare for and respond to active Zika transmission they may experience.

“The mosquitoes that carry Zika virus are already active in U.S. territories, hundreds of travelers with Zika have already returned to the continental U.S., and we could well see clusters of Zika virus in the continental U.S. in the coming months. Urgent action is needed, especially to minimize the risk of exposure during pregnancy,” said CDC Director Tom Frieden, M.D., M.P.H. “Everyone has a role to play. With federal support, state and local leaders and their community partners will develop a comprehensive action plan to fight Zika in their communities.”

Summit attendees will hear the latest scientific knowledge about Zika, including implications for pregnant women and strategies for mosquito control. The meeting also includes opportunities to learn about best communications practices; identify possible gaps in preparedness and response at the federal, state, and local levels; and help begin to address those gaps, including through the refinement of draft Zika action plans. Representatives from state and local jurisdictions will meet with experts to get technical assistance and guidance on their Zika action plans.

“The Administration is coordinating a whole-of-government effort to ensure that we are taking all available steps to prepare for Zika and work together with state, local, tribal, and territorial officials to protect Americans,” said Amy Pope, J.D., White House Deputy Homeland Security Advisor and Deputy Assistant to the President. “That’s why President Obama has requested $1.9 billion to prepare for, detect, and respond to any potential Zika outbreaks here at home, and limit the spread in other countries.”

Presenters will include CDC experts on Zika’s risk to pregnant women and their fetuses, identification and diagnosis of Zika, mosquito control, and what local and state leaders can do. Representatives from Florida, New York City, Texas, and Puerto Rico will discuss state and local response to other mosquito-borne diseases, including chikungunya, dengue, and West Nile virus.

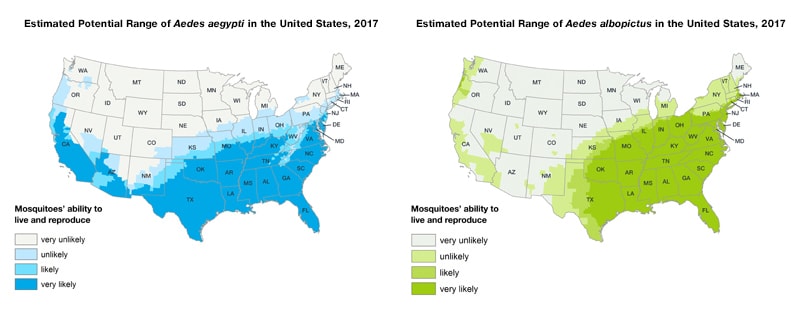

Also today, CDC released a Vital Signs report with information that reinforces previous CDC guidance and suggested actions that pregnant women and their partners can take to prevent Zika virus infection during pregnancy. The Vital Signs report describes what the U.S. government is doing, what state and local public health agencies and healthcare providers can do, and what can be done to prevent mosquito bites that potentially spread Zika. The report also includes an updated map of the U.S. with the latest available information on where the mosquitoes that can transmit the virus have been found.

Zika virus disease is caused by Zika virus that is spread to people primarily through the bite of infected Aedes aegypti and Aedes albopictus mosquitoes, though Aedes aegypti are more likely to spread Zika. Sexual transmission also has been documented. There is currently no vaccine or treatment for Zika. The most common symptoms of Zika are fever, rash, joint pain, and conjunctivitis (red eyes). In previous outbreaks, the illness has typically been mild with symptoms lasting for several days to a week after being bitten by an infected mosquito. However, mounting evidence links Zika virus infection in pregnant women with a serious birth defect of the brain called microcephaly. Zika also has been linked to Guillain-Barré syndrome (GBS), an uncommon sickness of the nervous system in which a person’s immune system damages the nerve cells, causing muscle weakness and sometimes paralysis.

Portions of the Zika Action Plan Summit are available via live webcast. For more information about the webcast or summit, visit: http://www.cdc.gov/zap/index.html.

** Zika virus disease in the United States, 2015–2016

Saturday, April 2nd, 2016Zika virus disease in the United States, 2015–2016

As of March 30, 2016 (5 am EST)

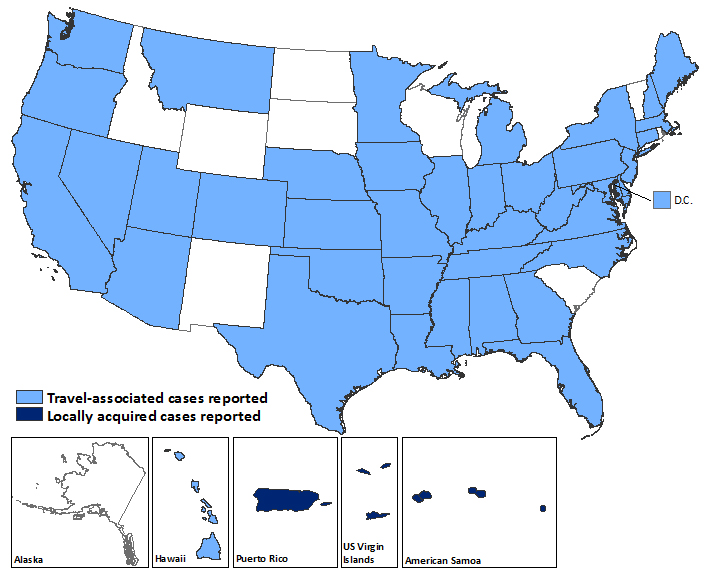

- Zika virus disease and Zika virus congenital infection are nationally notifiable conditions.

- This update from the CDC Arboviral Disease Branch includes provisional data reported to ArboNET for January 1, 2015 – March 30, 2016.

US States

- Travel-associated Zika virus disease cases reported: 312

- Locally acquired vector-borne cases reported: 0

- Of the 312 cases reported, 27 were pregnant women, 6 were sexually transmitted, and 1 had Guillain-Barré syndrome

US Territories

- Travel-associated cases reported: 3

- Locally acquired cases reported: 349

- Of the 352 cases reported, 37 were pregnant women and 1 had Guillain-Barré syndrome

Laboratory-confirmed Zika virus disease cases reported to ArboNET by state or territory — United States, 2015–2016 (as of March 30, 2016)

| States | Travel-associated cases* No. (%) (N=312) |

Locally acquired cases† No. (%) (N=0) |

|---|---|---|

| Alabama | 2 (1) | 0 (0) |

| Arizona | 1 (<1) | 0 (0) |

| Arkansas | 1 (<1) | 0 (0) |

| California | 17 (6) | 0 (0) |

| Colorado | 2 (1) | 0 (0) |

| Connecticut | 1 (<1) | 0 (0) |

| Delaware | 3 (1) | 0 (0) |

| District of Columbia | 3 (1) | 0 (0) |

| Florida | 74 (24) | 0 (0) |

| Georgia | 9 (3) | 0 (0) |

| Hawaii | 5 (2) | 0 (0) |

| Illinois | 9 (3) | 0 (0) |

| Indiana | 5 (2) | 0 (0) |

| Iowa | 4 (1) | 0 (0) |

| Kansas | 1 (<1) | 0 (0) |

| Kentucky | 3 (1) | 0 (0) |

| Louisiana | 2 (1) | 0 (0) |

| Maine | 1 (<1) | 0 (0) |

| Maryland | 6 (2) | 0 (0) |

| Massachusetts | 7 (2) | 0 (0) |

| Michigan | 2 (1) | 0 (0) |

| Minnesota | 12 (4) | 0 (0) |

| Mississippi | 2 (1) | 0 (0) |

| Missouri | 1 (<1) | 0 (0) |

| Montana | 1 (<1) | 0 (0) |

| Nebraska | 2 (1) | 0 (0) |

| Nevada | 2 (<1) | 0 (0) |

| New Hampshire | 2 (1) | 0 (0) |

| New Jersey | 5 (1) | 0 (0) |

| New York | 46 (15) | 0 (0) |

| North Carolina | 7 (2) | 0 (0) |

| Ohio | 9 (3) | 0 (0) |

| Oklahoma | 3 (1) | 0 (0) |

| Oregon | 6 (2) | 0 (0) |

| Pennsylvania | 11 (4) | 0 (0) |

| Tennessee | 1 (<1) | 0 (0) |

| Texas | 27 (9) | 0 (0) |

| Utah | 2 (1) | 0 (0) |

| Virginia | 8 (3) | 0 (0) |

| Washington | 2 (1) | 0 (0) |

| West Virginia | 5 (2) | 0 (0) |

| Territories | (N=3) | (N=349) |

| American Samoa | 0 (0) | 14 (4) |

| Puerto Rico | 2 (67) | 325 (93) |

| US Virgin Islands | 1 (33) | 10 (3) |

*Travelers returning from affected areas, their sexual contacts, or infants infected in utero

†Presumed local mosquito-borne transmission

** CDC Maps: Aedes albopictus and aegyptii in the USA

Friday, April 1st, 2016** Zika Virus: Many people in U.S. households where someone is pregnant or considering getting pregnant in the next 12 months are not aware of key facts about Zika virus

Thursday, March 31st, 2016

Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health

“….The researchers found:

- Approximately one in four (23%) are not aware of the association between Zika virus and the birth defect microcephaly.

- One in five (20%) believe, incorrectly, that there is a vaccine to protect against Zika virus.

- Approximately four in 10 (42%) do not realize Zika virus can be sexually transmitted.

- A quarter (25%) think individuals infected with Zika virus are “very likely” to show symptoms

- Four in 10 mistakenly believe Zika virus infection in women likely to harm future pregnancies

- About one in five (22%) are not aware that Zika virus can be transmitted from mother to baby during pregnancy

- More than a quarter (29%) are unaware it can be transmitted through blood transfusions.

- Four in 10 (40%) are unaware that it can be transmitted sexually.

- About a third (31%) believe, incorrectly, that Zika virus is transmitted through coughing and sneezing

- Nearly three-quarters of the public (71%) are unaware of a link between Zika virus and Guillain-Barré syndrome, which can cause paralysis. ……”

First new Zika animal model: The mouse

Tuesday, March 29th, 2016

** Several research institutions and companies have vaccine and drug candidates nearly ready to test, but until now a mouse model – a critical stage in preclinical testing – has not been available.

Characteristics of 115 residents of U.S. states and the District of Columbia with laboratory evidence of Zika virus disease — January 1, 2015–February 26, 2016

Monday, March 28th, 2016Travel-Associated Zika Virus Disease Cases Among U.S. Residents — United States, January 2015–February 2016

Weekly / March 25, 2016 / 65(11);286–289

Summary

What is already known about this topic?Zika virus is an emerging mosquito-borne flavivirus. Recent outbreaks of Zika virus disease in the Pacific Islands and the Region of the Americas have identified new modes of transmission and clinical manifestations, including adverse pregnancy outcomes.

What is added by this report?During January 1, 2015–February 26, 2016, a total of 116 residents of U.S. states and the District of Columbia had laboratory evidence of recent Zika virus infection based on testing performed at CDC, including one congenital infection and 115 persons who reported recent travel to areas with active Zika virus transmission (n = 110) or sexual contact with such a traveler (n = 5).

What are the implications for public health practice?Health care providers should educate patients about the risks for Zika virus disease and measures to prevent Zika virus infection and other mosquito-borne infections. Zika virus disease should be considered in patients with acute onset of fever, rash, arthralgia, or conjunctivitis who traveled to areas with ongoing transmission or had unprotected sex with someone who traveled to those areas and developed compatible symptoms within 2 weeks of returning.

Zika virus is an emerging mosquito-borne flavivirus. Recent outbreaks of Zika virus disease in the Pacific Islands and the Region of the Americas have identified new modes of transmission and clinical manifestations, including adverse pregnancy outcomes. However, data on the epidemiology and clinical findings of laboratory-confirmed Zika virus disease remain limited. During January 1, 2015–February 26, 2016, a total of 116 residents of 33 U.S. states and the District of Columbia had laboratory evidence of recent Zika virus infection based on testing performed at CDC. Cases include one congenital infection and 115 persons who reported recent travel to areas with active Zika virus transmission (n = 110) or sexual contact with such a traveler (n = 5). All 115 patients had clinical illness, with the most common signs and symptoms being rash (98%; n = 113), fever (82%; 94), and arthralgia (66%; 76). Health care providers should educate patients, particularly pregnant women, about the risks for, and measures to prevent, infection with Zika virus and other mosquito-borne viruses. Zika virus disease should be considered in patients with acute onset of fever, rash, arthralgia, or conjunctivitis, who traveled to areas with ongoing Zika virus transmission (http://www.cdc.gov/zika/geo/index.html) or who had unprotected sex with a person who traveled to one of those areas and developed compatible symptoms within 2 weeks of returning.

Zika virus is primarily transmitted to humans by Aedes aegypti mosquitoes (1). Most infections are asymptomatic (2). When occurring, clinical illness is generally mild and characterized by acute onset of fever, maculopapular rash, arthralgia, or nonpurulent conjunctivitis. Symptoms usually last from several days to a week. Severe disease requiring hospitalization is uncommon, and deaths are rare.

In addition to mosquito-borne transmission, Zika virus infections have been reported through intrauterine transmission resulting in congenital infection, intrapartum transmission from a viremic mother to her newborn, sexual transmission, and laboratory exposure (3,4). Increasing evidence suggests that Zika virus infection during pregnancy can result in microcephaly, other congenital anomalies, and fetal losses (5). Guillain-Barré syndrome also has been associated with recent Zika virus disease (6). However, the frequency of these outcomes is not known. To characterize Zika virus disease among U.S. residents, CDC reviewed demographics, exposures, and reported symptoms of patients with laboratory-evidence of recent Zika virus infection in the United States.

Zika virus disease cases among residents of U.S. states with specimens tested at CDC’s Arboviral Diseases Branch during January 1, 2015–February 26, 2016 were identified. The cases included in this report had laboratory evidence of Zika virus infection based on the following findings in serum: 1) Zika virus RNA detected by reverse transcription-polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR); 2) anti-Zika virus immunoglobulin M (IgM) antibodies detected by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) with ≥4-fold higher neutralizing antibody titers against Zika virus compared with neutralizing antibody titers against dengue virus; or 3) anti-Zika virus IgM antibodies with <4-fold difference in neutralizing antibody titers between Zika and dengue viruses and a direct epidemiologic link to a person with laboratory evidence of recent Zika virus infection (i.e., vertical transmission from mother to baby or sexual contact). State and local health departments collected information on patient demographics, dates of travel, and clinical signs and symptoms.

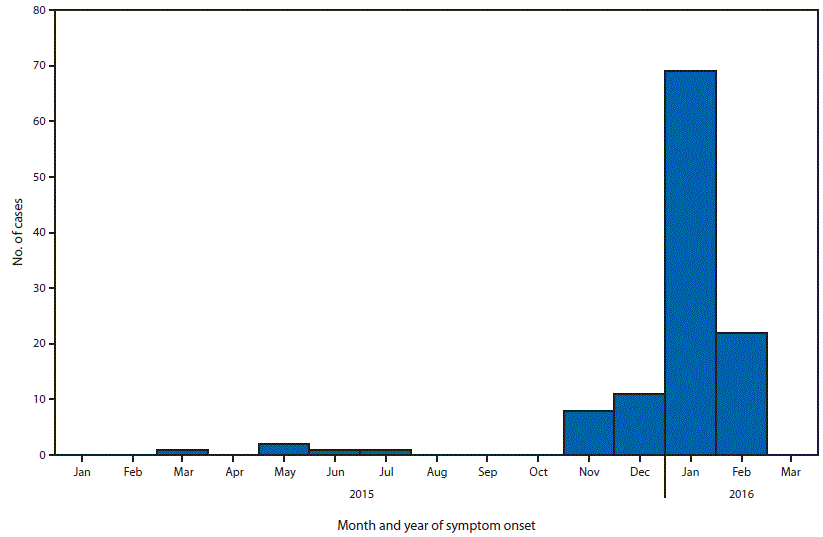

During January 1, 2015–February 26, 2016, a total of 116 residents of 33 states and the District of Columbia with laboratory evidence of recent Zika virus infection were identified on the basis of testing at CDC. One case occurred in a full-term infant born with severe congenital microcephaly, whose mother had Zika virus disease in Brazil during the first trimester of pregnancy (5). Among the remaining 115 patients (including the infant’s mother), 24 (21%) had illness onset in 2015 and 91 (79%) in 2016. Seventy-five (65%) cases occurred in females (Table 1). The median age of patients was 38 years (range = 3–81 years); 11 (10%) cases occurred in children and adolescents aged <18 years. Of the 115 patients, 110 (96%) reported recent travel to areas of active Zika virus transmission and five (4%) did not travel but reported sexual contact with a traveler who had symptomatic illness. The most frequently reported countries with active Zika virus transmission visited by patients were Haiti (n = 27), El Salvador (16), Colombia (11), Honduras (11), and Guatemala (10).

All 115 patients reported a clinical illness with onset during March 2015–February 2016 (Figure). The most commonly reported signs and symptoms were rash (98%), fever (82%), arthralgia (66%), headache (57%), myalgia (55%), and conjunctivitis (37%) (Table 2). Among all 115 patients, 110 (96%) reported two or more of the following symptoms: rash, fever, arthralgia, and conjunctivitis; 75 (65%) reported three or more of these signs or symptoms. Four (3%) patients were hospitalized; no deaths occurred. Among the 109 travelers who had known travel dates, patients reported becoming ill a median of 1 day after returning home (range = 37 days before return to 11 days after return).

Laboratory evidence of Zika virus infection included positive RT-PCR test results in 28 (24%) cases and positive serologic test results in 87 (76%) cases; two (2%) cases had serologic evidence of a recent unspecified flavivirus infection and were classified as Zika virus disease cases based on their epidemiologic link to a confirmed case (one vertical transmission and one sexual contact).

Discussion

Before 2015, Zika virus disease among U.S. travelers was uncommon. This likely was because of low levels of Zika virus transmission in travel destinations and limited disease recognition in the United States. Local mosquito-borne transmission of Zika virus has not been documented in U.S. states. With the recent outbreaks in the Americas, the number of Zika virus disease cases among travelers visiting or returning to the United States has increased and will likely continue to increase. These imported cases might result in local human-to-mosquito-to-human transmission of the virus in U.S. states that have the appropriate mosquito vectors.

This report increases the number of laboratory-confirmed sexually transmitted Zika virus disease cases reported in the United States; two cases included here were previously reported as probable cases and were confirmed through additional testing (4). Sexually transmitted cases will be increasingly recognized among contacts of returning travelers and there is risk for congenital, perinatal, or transfusion-associated transmission. CDC has issued guidelines to reduce the risk for travel-associated infections, especially among pregnant women and sexual contacts of travelers (4,7). Temporary deferral of blood donors with recent travel to Zika-affected areas also has been recommended to reduce the risk for transfusion-associated transmission (8).

The cases presented in this report have clinical findings similar to those of Zika virus disease cases previously reported from other countries. Most had fever and rash; however, rates of conjunctivitis are lower than those seen in previous outbreaks (2). The majority (95%) of cases occurred in travelers to areas with ongoing mosquito-borne Zika virus transmission.

This evaluation was limited to cases with testing performed at CDC through February 26, 2016. Zika virus RT-PCR and anti-Zika IgM antibody testing is now available at an increasing number of state, territorial, and local health departments, and additional cases have been diagnosed and reported from state and territorial health departments beyond those included in this report (http://www.cdc.gov/zika/geo/united-states.html). On February 26, 2016, the Council of State and Territorial Epidemiologists (CSTE) approved interim case definitions for Zika virus disease and Zika virus congenital infection and added them to the list of nationally notifiable conditions (9). Subsequent reports of Zika virus disease cases will include cases reported to ArboNET, the national arboviral surveillance system, using the interim CSTE case definitions.

Health care providers should educate patients about the risks for Zika virus disease and measures to prevent Zika virus infection and other mosquito-borne infections. Zika virus disease should be considered in patients with acute onset of fever, rash, arthralgia, or conjunctivitis who traveled to areas with ongoing transmission or had unprotected sex with someone who traveled to those areas and developed compatible symptoms within 2 weeks of returning. Until more is known about the effects of Zika virus infection on the developing fetus, pregnant women should postpone travel to areas where Zika virus transmission is ongoing. Pregnant women who do travel to one of these areas should talk to their health care provider before traveling and strictly follow steps to avoid mosquito bites (http://www.cdc.gov/features/stopmosquitoes/) during travel. Pregnant women who develop a clinically compatible illness during or within 2 weeks of returning from an area with Zika virus transmission should be tested for Zika virus infection; testing may also be offered to asymptomatic pregnant women 2–12 weeks after travel to an area with active Zika transmission (7). Fetuses and infants of women infected with Zika virus during pregnancy should be evaluated for possible congenital infection (10). CDC has established a registry to collect information on Zika virus infection during pregnancy and congenital infection.

Health care providers are encouraged to report suspected Zika virus disease cases to their state or local health departments to facilitate diagnosis and mitigate the risk for local transmission in areas where Aedes aegypti or Aedes albopictus mosquitoes are currently active. State health departments should report laboratory-confirmed cases of Zika virus disease to CDC (8).

References

- Hayes EB. Zika virus outside Africa. Emerg Infect Dis 2009;15:1347–50 . CrossRef PubMed

- Duffy MR, Chen TH, Hancock WT, et al. Zika virus outbreak on Yap Island, Federated States of Micronesia. N Engl J Med 2009;360:2536–43 . CrossRef PubMed

- European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control. Zika virus disease epidemic: potential association with microcephaly and Guillain-Barré syndrome. Stockholm, Sweden: European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control; 2016. http://ecdc.europa.eu/en/publications/Publications/zika-virus-rapid-risk-assessment-9-march-2016.pdf

- Hills SL, Russell K, Hennessey M, et al. Transmission of Zika virus through sexual contact with travelers to areas of ongoing transmission—continental United States, 2016. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2016;65:215–6 . CrossRef PubMed

- Meaney-Delman D, Hills SL, Williams C, et al. Zika virus infection among US pregnant travelers—August 2015–February 2016. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2016;65:211–4 . CrossRef PubMed

- Cao-Lormeau VM, Blake A, Mons S, et al. Guillain-Barré syndrome outbreak associated with Zika virus infection in French Polynesia: a case-control study. Lancet. Epub, March 2, 2016. CrossRef PubMed

- Oduyebo T, Petersen EE, Rasmussen SA, et al. Update: interim guidelines for health care providers caring for pregnant women and women of reproductive age with possible Zika virus exposure—United States, 2016. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2016;65:122–7 . CrossRef PubMed

- US Food and Drug Administration. Recommendations for donor screening, deferral, and product management to reduce the risk of transfusion-transmission of Zika virus. Washington, DC: US Food and Drug Administration; 2016. http://www.fda.gov/downloads/BiologicsBloodVaccines/GuidanceComplianceRegulatoryInformation/Guidances/Blood/UCM486360.pdf

- Council of State and Territorial Epidemiologists. Zika virus disease and congenital Zika virus infection interim case definition and addition to the Nationally Notifiable Disease List. Atlanta, GA: Council of State and Territorial Epidemiologists; 2016. https://www.cste2.org/docs/Zika_Virus_Disease_and_Congenital_Zika_Virus_Infection_Interim.pdf

- Fleming-Dutra KE, Nelson JM, Fischer M, et al. Update: interim guidelines for health care providers caring for infants and children with possible Zika virus infection—United States, February 2016. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2016;65:182–7 . CrossRef PubMed

TABLE 1. Characteristics of 115 residents of U.S. states and the District of Columbia with laboratory evidence of Zika virus disease — January 1, 2015–February 26, 2016*,†

TABLE 1. Characteristics of 115 residents of U.S. states and the District of Columbia with laboratory evidence of Zika virus disease — January 1, 2015–February 26, 2016*,†

| Characteristic | No. (%) |

|---|---|

| Female | 75 (65) |

| Age group (yrs) | |

| <10 | 4 (3) |

| 10–19 | 10 (9) |

| 20–29 | 23 (20) |

| 30–39 | 22 (19) |

| 40–49 | 19 (17) |

| 50–59 | 23 (20) |

| 60–69 | 13 (11) |

| ≥70 | 1 (1) |

| Region visited | |

| Central America | 42 (37) |

| Caribbean | 38 (33) |

| South America | 21 (18) |

| Southeast Asia and Pacific Islands | 7 (6) |

| North America (Mexico) | 2 (2) |

| No travel§ | 5 (4) |

| Hospitalized | 4 (3) |

| Died | 0 (0) |

* Testing performed at CDC’s Arboviral Diseases Branch laboratory.

† Excludes one infant born with severe congenital microcephaly after maternal infection in Brazil during the first trimester of pregnancy.

§ Sexual contacts of travelers.

FIGURE. Month of illness onset for 115 patients with laboratory evidence of Zika virus infection among residents of U.S. states and the District of Columbia — January 1, 2015–February 26, 2016*

FIGURE. Month of illness onset for 115 patients with laboratory evidence of Zika virus infection among residents of U.S. states and the District of Columbia — January 1, 2015–February 26, 2016*

*Testing performed at CDC’s Arboviral Diseases Branch laboratory.

TABLE 2. Clinical signs and symptoms reported by 115 residents of U.S. states and the District of Columbia with laboratory evidence of Zika virus disease — January 1, 2015–February 26, 2016*

TABLE 2. Clinical signs and symptoms reported by 115 residents of U.S. states and the District of Columbia with laboratory evidence of Zika virus disease — January 1, 2015–February 26, 2016*

| Yes† | No | Unknown | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sign/symptom | No. (%) | No. (%) | No. (%) |

| Rash | 113 (98) | 1 (1) | 1 (1) |

| Fever | 94 (82) | 20 (17) | 1 (1) |

| Arthralgia | 76 (66) | 33 (29) | 6 (5) |

| Headache | 65 (57) | 37 (32) | 13 (11) |

| Myalgia | 63 (55) | 38 (33) | 14 (12) |

| Conjunctivitis | 43 (37) | 53 (46) | 19 (17) |

| Diarrhea | 22 (19) | 63 (55) | 30 (26) |

| Vomiting | 6 (5) | 79 (69) | 30 (26) |

* Testing performed at CDC’s Arboviral Diseases Branch laboratory.

† Some patients had more than one sign and/or symptom.

Suggested citation for this article: Armstrong P, Hennessey M, Adams M, et al. Travel-Associated Zika Virus Disease Cases Among U.S. Residents — United States, January 2015–February 2016. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2016;65:286–289. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.15585/mmwr.mm6511e1.

Zika Virus: Puerto Rico & Contraceptives

Monday, March 28th, 2016Estimating Contraceptive Needs and Increasing Access to Contraception in Response to the Zika Virus Disease Outbreak — Puerto Rico, 2016

Naomi K. Tepper, MD; Howard I. Goldberg, PhD; Manuel I. Vargas Bernal, MD; et al.

MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2016;65(Early Release)

As of March 16, 2016, the highest number of Zika virus disease cases in the United States and U.S. territories were reported from Puerto Rico. Increasing evidence links Zika virus infection during pregnancy to adverse pregnancy and birth outcomes. High rates of unintended and adolescent pregnancies in Puerto Rico suggest access to contraception might need to be improved in the context of this outbreak