Archive for December, 2015

In September and October 2015, tens of thousands of fires sent clouds of toxic gas and particulate matter into the air over Indonesia.

Friday, December 11th, 2015In September and October 2015, tens of thousands of fires sent clouds of toxic gas and particulate matter into the air over Indonesia. Despite the moist climate of tropical Asia, fire is not unusual during those months. For the past few decades, people have used fire to clear land for farming and to burn away leftover crop debris. What was unusual in 2015 was how many fires burned and how many escaped their handlers and went uncontrolled for weeks and even months.

To study the fires, scientists in Indonesia and around the world have been using many different tools—from sensors on the ground to data collected by satellites. The goal is to better understand why the fires became so severe, how they are affecting human health and the atmosphere, and what can be done to prepare for similar surges in fire activity in the future.

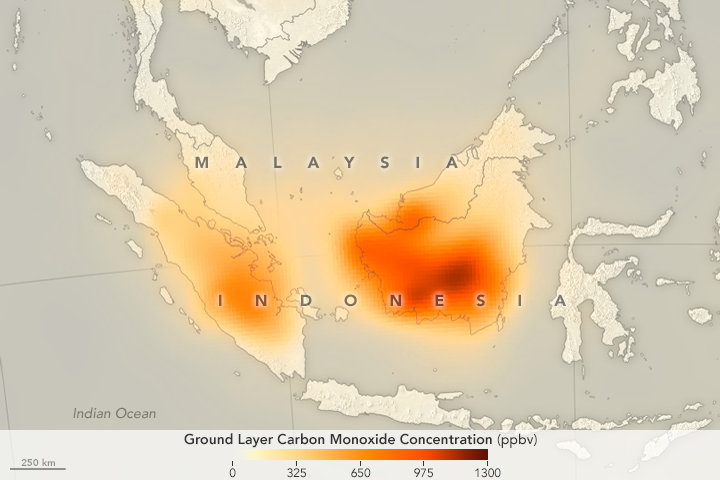

While some NASA satellite instruments captured natural-color images of the smoky pall, others focused on gases that are invisible to human eyes. For instance, the Measurement of Pollution in the Troposphere (MOPITT) sensor on Terra can detect carbon monoxide, an odorless, colorless, and poisonous gas. As shown by the map above, the concentration of carbon monoxide near the surface was remarkably high in September 2015 over Sumatra and Kalimantan.

“The 2015 Indonesian fires produced some of the highest concentrations of carbon monoxide that we have ever seen with MOPITT,” said Helen Worden, a scientist at the National Center for Atmospheric Research. Average carbon monoxide concentrations over Indonesia are usually about 100 parts per billion. In some parts of Borneo in 2015, MOPITT measured carbon monoxide concentrations at the surface up to nearly 1,300 parts per billion.

While all types of wildfires emit carbon monoxide as part of he combustion process, the fires in Indonesia released large amounts of the gas because in many cases the fuel burning was peat, a soil-like mixture of partly decayed plant material that builds up in wetlands, swamps, and partly submerged landscapes.

Read more about studies of Indonesia’s fire season in our new feature: Seeing Through the Smoky Pall.

NASA Earth Observatory map by Joshua Stevens and Jesse Allen, using data from the MOPITT Teams at the National Center for Atmospheric Research and the University of Toronto. Caption by Adam Voiland.

- Instrument(s):

- Terra – MOPITT

Historic Rainfall Floods Southeast India

Friday, December 11th, 2015

NASA: On December 1–2, 2015, the Indian city of Chennai received more rainfall in 24 hours than it had seen on any day since 1901. The deluge followed a month of persistent monsoon rains that were already well above normal for the Indian state of Tamil Nadu. At least 250 people have died, several hundred have been critically injured, and thousands have been affected or displaced by the flooding that has ensued.

World Malaria Report 2015: 57 of the 106 countries with malaria in 2000 had achieved reductions in new malaria cases of at least 75% by 2015. In that same time frame, 18 countries reduced their malaria cases by 50-75%.

Thursday, December 10th, 2015New report signals country progress in the path to malaria elimination

9 DECEMBER 2015 ¦ Brussels – New estimates from WHO show a significant increase in the number of countries moving towards malaria elimination, with prevention efforts saving millions of dollars in healthcare costs over the past 14 years in many African countries.

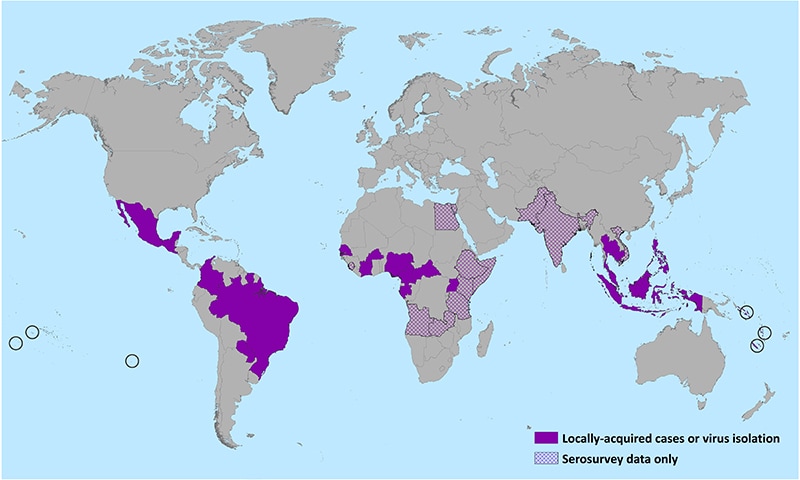

According to the “World Malaria Report 2015”, released today, more than half (57) of the 106 countries with malaria in 2000 had achieved reductions in new malaria cases of at least 75% by 2015. In that same time frame, 18 countries reduced their malaria cases by 50-75%.

Across sub-Saharan Africa, the prevention of new cases of malaria has resulted in major cost savings for endemic countries. New estimates presented in the WHO report show that reductions in malaria cases attributable to malaria control activities saved an estimated US$ 900 million in case management costs in the region between 2001 and 2014. Insecticide-treated mosquito nets contributed the largest savings, followed by artemisinin-based combination therapies and indoor residual spraying.

“Since the start of this century, investments in malaria prevention and treatment have averted over 6 million deaths,” said Dr Margaret Chan, WHO Director-General. “We know what works. The challenge now is to do even more.”

Regional progress

For the first time since WHO began keeping score, the European Region is reporting zero indigenous cases of malaria. This achievement was made possible through strong country-level leadership, technical support from WHO and financial assistance from the Global Fund to Fight AIDS, Tuberculosis and Malaria.

Since 2000, the malaria mortality rate has declined by 85% in the South-East Asia Region, by 72% in the Region of the Americas, by 65% in the Western Pacific Region, and by 64% in the Eastern Mediterranean Region. While the African Region continues to carry the highest malaria burden, here too there have been impressive gains: over the last 15 years, malaria mortality rates fell by 66% among all age groups, and by 71% among children under five, a population particularly susceptible to the disease.

Progress towards global targets

Country-level and regional progress in malaria control is reflected in global disease trends. Since 2000, malaria incidence and death rates have fallen by 37% and 60%, respectively, around the world. Among children under five, malaria death rates have declined by 65%. An estimated 6.2 million deaths have been averted since 2000.

According to the report, Target 6C of the Millennium Development Goals—which aimed to halt and reverse the global incidence of malaria between 2000 and 2015—has been achieved. Substantial progress has also been made towards the 2005 World Health Assembly target of a 75% reduction in the global burden of malaria by 2015.

Scale-up in malaria control

Progress has resulted, in large part, from the massive deployment of effective and low-cost malaria control interventions. Since 2000, nearly 1 billion insecticide-treated mosquito nets have been distributed in sub-Saharan Africa. By 2015, about 55% of the population in this region was sleeping under mosquito nets, up from less than 2% coverage in 2000.

Rapid diagnostic tests have made it easier to swiftly distinguish between malarial and non-malarial fevers, enabling timely and appropriate treatment. A sharp increase in diagnostic testing for malaria has been reported in the WHO African Region: from 36% of suspected malaria cases in 2005 to 65% of cases in 2014. Artemisinin-based combination therapies (ACTs), introduced widely over the past decade, have been highly effective against P. falciparum, the most prevalent and lethal malaria parasite affecting humans.

An estimated 663 million cases of malaria have been averted in sub-Saharan Africa since 2001 as a direct result of the scale-up of three key malaria control interventions: insecticide-treated mosquito nets, indoor residual spraying and artemisinin-based combination therapy. Mosquito nets have had the greatest impact, accounting for about 68% of cases prevented through these interventions.

Still a long road

Despite progress, significant challenges remain. Globally, about 3.2 billion people—nearly half of the world’s population—are at risk of malaria. In 2015, there were estimated 214 million new cases of malaria, and approximately 438 000 deaths.

Fifteen countries, mainly in Africa, account for most global malaria cases (80%) and deaths (78%). According to the report, these high burden countries have achieved slower-than-average declines in malaria incidence (32%) compared to other countries globally (53%). In many of these countries, weak health systems continue to impede progress in malaria control.

Millions of people are still not receiving the services they need to prevent and treat malaria. In 2014, approximately one third of people at risk of malaria in sub-Saharan Africa lived in households that lacked protection from mosquito nets or indoor residual spraying.

Insecticide and drug resistance

“As the global burden of malaria declines, new challenges have emerged,” says Dr Pedro Alonso, Director of the WHO Global Malaria Programme. “In many countries, progress is threatened by the rapid development and spread of mosquito resistance to insecticides. Drug resistance could also jeopardize recent gains in malaria control.”

Since 2010, 60 of the 78 countries that monitor insecticide resistance have reported mosquito resistance to at least one insecticide used in nets and indoor spraying; of these, 49 reported resistance to two or more insecticide classes. Parasite resistance to artemisinin— the core compound of the best available antimalarial medicines—has been detected in 5 countries of the Greater Mekong subregion.

Closing gaps

In May 2015, the World Health Assembly adopted the WHO “Global Technical Strategy for Malaria 2016-2030”, a new 15-year framework for malaria control in all endemic countries. The strategy sets ambitious but achievable targets for 2030, including a reduction in global malaria incidence and mortality of at least 90%; the elimination of malaria in at least 35 countries; and the prevention of a resurgence of malaria in all countries that are malaria free.

Achieving these targets will require country leadership, sustained political commitment and a tripling of global investment for malaria control: from the US $2.7 billion in annual funding available today to US $8.7 billion in annual funding by 2030. This figure takes into account future savings in case management costs anticipated as malaria control efforts continue to expand and more cases are averted.

Other key findings from the report

- Globally, the number of malaria cases fell from an estimated 262 million in 2000 (range 205–316 million) to 214 million in 2015 (range 149–303 million).

- Globally, the number of malaria deaths fell from an estimated 839 000 in 2000 (range 653 000 to 1.1 million), to 438 000 in 2015 (range 236 000–635 000).

- Among children under five, the estimated number of malaria deaths, globally, fell from 723 000 in 2000 (range 563 000–948 000) to 306 000 in 2015 (range 219 000–421 000). The bulk of this decrease occurred in the WHO African Region.

- Most malaria cases (88%) and deaths (90%) occurred in the WHO African Region in 2015.

- Two countries, Nigeria and Democratic Republic of Congo, accounted for more than 35% of global malaria deaths in 2015.

- The WHO South-East Asia Region accounted for 10% of global malaria cases and 7% of deaths in 2015.

- The WHO Eastern Mediterranean Region accounted for 2% of global malaria cases and 2% of deaths in 2015.

- In 2014, 16 countries reported zero indigenous cases of malaria: Argentina, Armenia, Azerbaijan, Costa Rica, Iraq, Georgia, Kyrgyzstan, Morocco, Oman, Paraguay, Sri Lanka, Tajikistan, Turkey, Turkmenistan, United Arab Emirates and Uzbekistan. Seventeen countries are reporting fewer than 1000 cases of malaria.

Media contacts

Fadela Chaib

Communications Officer

Telephone: +41 22 791 3228+41 22 791 3228

Mobile: +41 79 475 5556+41 79 475 5556

Email: chaibf@who.int

Saira Stewart

Technical Officer

Telephone: +41 22 791 4217+41 22 791 4217

Mobile: +41 79 500 6538+41 79 500 6538

Email: stewarts@who.int

Lahore, Pakistan: Seven children have died of diphtheria during the last few weeks at the Children’s Hospital

Wednesday, December 9th, 2015

“…..diphtheria, which had almost been eliminated in most parts of the world, was thriving in few countries including Pakistan….”

Attacks on health workers

Wednesday, December 9th, 2015Tracking attacks on health workers – Don’t let them go unnoticed

In the early hours of 3 October, rockets slammed into a Médecins Sans Frontières (MSF) hospital in Kunduz, Afghanistan, killing at least 14 health workers and injuring 37. An MSF clinic in the southern Yemen city of Taiz was bombed on 2 December, injuring 9 people, including 2 MSF staff. Since 2012, almost 60% of hospitals in Syria have been partially or completely destroyed, and more than half of the country’s health workers have fled or been killed.

From Ukraine to Afghanistan, healthcare workers are in the line of fire. In 2014 alone, 603 health workers were killed and 958 injured in such attacks in 32 countries, according to data compiled by the WHO from a range of sources.

The attacks and deaths are tragic enough, but the loss of health workers, services and facilities results in less care for people, compounding the suffering caused by conflicts and other emergencies.

“Protecting health care workers is one of the most pressing responsibilities of the international community,” said Jim Campbell, director of WHO’s Health Workforce department. “Without health workers, there is no health care.”

Until now, data on attacks against health workers has been piecemeal and there has been no standard way of reporting them.

A new tracking system

To address that need WHO developed a new system for collecting data that is being tested in Central African Republic, Syrian Arab Republic and West Bank and Gaza Strip. It will be available for use early next year. But the project doesn’t only aim to collect data. It also plans to use the information to identify patterns and find ways to avoid attacks or mitigate their consequences.

“Every time a doctor is too afraid to come to work, or a hospital is bombed, or supplies are looted, it impedes access to health care,” said Erin Kenney, who manages the WHO project that has developed the new system.

In Pakistan, where 32 health care workers and other personnel involved in polio eradication have been killed since 2012, there have been fewer incidents since vaccinators switched from four-day campaigns to one-day campaigns, and studied the safest times to dispatch vaccinators.

“It’s being clever about the way we do things,” Kenney said. “We’re negotiating access routes so we can get people in and out, evacuate hospitals, and pre-position supplies so hospitals can be resilient.”

Protecting health workers

Attacks on hospitals and clinics in conflict situations are just one of the threats health workers face. During West Africa’s Ebola epidemic, a team of 8 people trying to raise awareness about the outbreak were killed in Guinea amid a climate of fear and suspicion. More than 400 health workers lost their lives after becoming infected while treating Ebola patients.

The WHO’s first global report on attacks against health will be published next year.

In December 2014, the United Nations General Assembly agreed to strengthen international efforts to ensure the safety of health personnel and to collect data on threats and attacks against health workers. A WHO report calling for measures to improve security for workers and health-care for patients is being presented to the assembly this month.

WHO has also developed a global strategy to help countries address health workforce challenges as they progress towards universal health coverage. In fragile states and countries in chronic emergencies, the strategy calls for additional protection of health workers from violence and harm.