Archive for April, 2018

Measles cases continue to increase in a number of EU/EEA countries with the highest number of cases to date in 2018 were in Romania (1 709), Greece (1 463) France (1 346) and Italy (411) respectively.

Tuesday, April 17th, 2018MERS-CoV and a large outbreak in Riyadh during 2017

Tuesday, April 17th, 2018Unusual presentation of Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus leading to a large outbreak in Riyadh during 2017

“…..Between May 31 and June 15, 2017, 44 cases of MERS-CoV infection were reported from 3 simultaneous clusters from 3 health care facilities in Riyadh, Saudi Arabia, including 11 fatal cases. Out of the total reported cases, 29 cases were reported from King Saud Medical City. The cluster at King Saud Medical City was ignited by a single superspreader patient who presented with acute renal failure…..”

A giant explosion occurs during the loading of fertilizer onto the freighter Grandcamp at a pier in Texas City, Texas: 4/16/1947.

Monday, April 16th, 20184/15/1912: The “unsinkable” RMS Titanic sinks into the icy waters of the North Atlantic after hitting an iceberg on its maiden voyage, killing 1,517 people.

Sunday, April 15th, 2018French Republic Assessment of Chemical Attack in Douma, Syria April 2018.

Sunday, April 15th, 2018National assessment

Chemical attack of 7 April 2018 (Douma, Eastern Ghouta, Syria)

Syria’s clandestine chemical weapons programme

April 14, 2018

This document is based on technical analyses of open source information and declassified intelligence obtained by French services.

2

I. SEVERAL LETHAL CHEMICAL ATTACKS TOOK PLACE IN THE TOWN OF DOUMA IN THE LATE AFTERNOON OF SATURDAY, 7 APRIL 2018, AND WE ASSESS WITH A HIGH DEGREE OF CONFIDENCE THAT THEY WERE CARRIED OUT BY THE SYRIAN REGIME.

Following the Syrian regime’s resumption of its military offensive, as well as high levels of air force activity over the town of Douma in Eastern Ghouta, two new cases of toxic agents employment were spontaneously reported by civil society and local and international media from the late afternoon of 7 April. Non-governmental medical organizations active in Ghouta (the Syrian American Medical Society and the Union of Medical Care and Relief Organizations), whose information is generally reliable, publicly stated that strikes had targeted in particular local medical infrastructure on 6 and 7 April.

A massive influx of patients in health centres in Eastern Ghouta (at the very least 100 people) presenting symptoms consistent with exposure to a chemical agent was observed and documented during the early evening. In total, several dozens of people, more than forty according to several sources, are thought to have died from exposure to a chemical substance.

The information collected by France forms a body of evidence that is sufficient to attribute responsibility for the chemical attacks of 7 April to the Syrian regime.

1. – Several chemical attacks took place at Douma on 7 April 2018.

The French services analysed the testimonies, photos and videos that spontaneously appeared on specialized websites, in the press and on social media in the hours and days following the attack. Testimonies obtained by the French services were also analysed. After examining the videos and images of victims published online, they were able to conclude with a high degree of confidence that the vast majority are recent and not fabricated. The spontaneous circulation of these images across all social networks confirms that they were not video montages or recycled images. Lastly, some of the entities that published this information are generally considered reliable.

French experts analysed the symptoms identifiable in the images and videos that were made public. These images and videos were taken either in enclosed areas in a building where around 15 people died, or in local hospitals that received contaminated patients. These symptoms can be described as follows (cf. annexed images):

– Suffocation, asphyxia or breathing difficulties, – Mentions of a strong chlorine odour and presence of green smoke in affected areas, – Hypersalivation and hypersecretions (particularly oral and nasal), – Cyanosis, – Skin burns and corneal burns.

3

No deaths from mechanical injuries were visible. All of these symptoms are characteristic of a chemical weapons attack, particularly choking agents and organophosphorus agents or hydrocyanic acid. Furthermore, the apparent use of bronchodilators by the medical services observed in videos reinforces the hypothesis of intoxication by choking agents.

2. – Given in particular ongoing military operations in Eastern Ghouta around 7 April, we assess with a high degree of confidence that the Syrian regime holds responsibility.

Reliable intelligence indicates that Syrian military officials have coordinated what appears to be the use of chemical weapons containing chlorine on Douma, on April 7.

The attack of 7 April 2018 took place as part of a wider military offensive carried out by the regime on the Eastern Ghouta region. Launched in February 2018, this offensive has now enabled Damascus to regain control of the entire enclave.

As a reminder, the Russian military forces active in Syria enable the regime to enjoy unquestionable air superiority, giving it the total military freedom of action it needs for its indiscriminate offensives on urban areas.

The tactic adopted by pro-regime forces involved separating the various groups (Ahrar al-Sham, Faylaq al-Rahman, and Jaysh al-Islam) in order to focus their efforts and obtain negotiated surrender agreements. The three main armed groups therefore began separate negotiations with the regime and Russia. The first two groups (Ahrar al-Sham and Faylaq al-Rahman) concluded agreements that resulted in the evacuation of nearly 15,000 fighters and their families. During this first phase, the Syrian regime’s political and military strategy consisted in alternating indiscriminate military offensives against local populations, which sometimes included the use of chlorine, and pauses in operations for negotiations.

Negotiations with Jaysh al-Islam began in March but were not fully conclusive. On 4 April, part of the Jaysh al-Islam group (around one quarter of the group according to estimates) accepted the surrender agreement and fighters and their families were sent to Idlib (approximately 4,000 people, with families). However, between 4,500 and 5,500 Jaysh al-Islam fighters, mostly located in Douma, refused the terms of negotiation. As a result, from 6 April onwards, the Syrian regime, with support from Russian forces, resumed its intensive bombing of the area, ending a pause in ground and aerial operations that had been observed since negotiations began in mid-March. This was the context for the chemical strikes analysed in this document.

Given this context, the Syrian regime’s use of chemical weapons makes sense from both the military and strategic points of view:

Tactically speaking, this type of ammunition is used to flush out enemy fighters sheltering in homes and engage in urban combat in conditions that are more

4

favourable to the regime. It accelerates victory and has a multiplier effect that helps speed up the capitulation of the last bastion of armed groups.

Strategically speaking, chemical weapons and particularly chlorine, documented in Eastern Ghouta since early 2018, are especially used to punish civilian populations present in zones held by fighters opposed to the Syrian regime and to create a climate of terror and panic that encourages them to surrender. As the war is not over for the regime, it uses these indiscriminate strikes to show that resistance is futile and pave the way for capturing these last pockets of armed resistance.

Since 2012, the Syrian forces have repeatedly used the same pattern of military tactics: toxic chemicals are mainly used during wider urban offensives, as was the case in late 2016 during the recapture of Aleppo, where chlorine weapons were regularly used in conjunction with traditional weapons. The zones targeted, such as Eastern Ghouta, are all major military objectives for Damascus.

3. – The French services have no information to support the theory whereby the armed groups in Ghouta would have sought to acquire or have possessed chemical weapons.

The French services also assess that a manipulation of the images circulated massively from Saturday, 7 April is not credible, in part because the groups present in Ghouta do not have the resources to carry out a communications operation on such a scale.

II. SINCE APRIL 2017, THE SYRIAN REGIME HAS USED CHEMICAL WEAPONS AND TOXIC AGENTS IN ITS MILITARY OPERATIONS INCREASINGLY OFTEN.

4. – The Syrian regime has conserved a clandestine chemical weapons programme since 2013.

The French services assess that Syria did not declare all of its stockpiles and capacities to the Organisation for the Prohibition of Chemical Weapons (OPCW) during its late, half-hearted accession to the Chemical Weapons Convention (CWC) in October 2013.

Syria omitted, notably, to declare many of the activities of its Scientific Studies and Research Centre (SSRC). Only recently has it accepted to declare certain SSRC activities under the Chemical Weapons Convention (CWC), but not, however, all of them. Initially, it also failed to declare the sites at Barzeh and Jemraya, eventually doing so in 2018.

The French services assess that four questions asked of the Syrian regime by the OPCW and which have remained unanswered require particular attention, particularly in the context of these latest cases of the use of chemical weapons in Syria: – possible remaining stocks of yperite (mustard gas) and DF (a sarin precursor); – undeclared chemical weapons of small calibre which may have been used on several occasions, including during the attack on Khan Sheikhoun in April 2017;

5

– signs of the presence of VX and sarin on production and loading sites; – signs of the presence of chemical agents that have never been declared, including nitrogen mustard, lewisite, soman and VX.

Since 2014, the OPCW Fact-Finding Mission (FFM) has published several reports confirming the use of chemical weapons against civilians in Syria. The UN-OPCW Joint Investigation Mechanism (JIM) on chemical weapons attacks has investigated nine occasions when they have allegedly been used. In its August and October 2016 reports, the JIM attributed three cases of the use of chlorine to the Damascus regime and one case of the use of yperite to Daesh, but none to any Syrian armed group.

5. – A series of chemical attacks has taken place in Syria since 4 April 2017

A French national assessment published on 26 April 2017 following the Khan Sheikhoun attack listed all the chemical attacks in Syria since 2012, along with the assessment of their probability according to French services. This attack, carried out in two phases, at Latamneh on 30 March, and then at Khan Sheikhoun with sarin gas on 4 April, led to the death of more than 80 civilians. The French authorities considered at the time that it was very likely that the Syrian armed and security forces held responsibility for the attack.

The French services have identified 44 allegations of the use of chemical weapons and toxic agents since 4 April 2017, the date of the sarin attack on Khan Sheikhoun. Of these 44 allegations, the French services consider that the evidence collected around 11 of the attacks gave reason to assess they were of a chemical nature. Chlorine is believed to have been used in most cases, while the services also believe a neurotoxic agent was used at Harasta on 18 November 2017.

In this context, a considerable rise in cases of use can be noted since the non-renewal of the mechanism of the UN-OPCW Joint Investigation Mechanism (JIM) in November 2017 because of Russia’s veto at the UN Security Council. A considerable increase in chlorine attacks since the beginning of the offensive on Eastern Ghouta has also been clearly observed and proven. A series of attacks preceded the major attack of 7 April 2018, as part of a wider offensive (at least 8 chlorine attacks in Douma, Shayfounia and Hamouria).

*

These facts need to be considered in the light of a chemical warfare modus operandi of the Syrian regime that has been well documented since the attacks on Eastern Ghouta on 21 August 2013 and on Khan Sheikhoun on 4 April 2017. As part of a continuous increase in violence employed against civilians in enclaves refusing the regime’s authority, and in violation of its international obligations despite clear warnings from UN Security Council and OPCW members, Damascus seeks to seize a tactical military advantage locally, and above all to terrorize populations in order to break down all remaining resistance. It can be noted that, since the attacks of

6

7 April 2018, the group Jaysh al-Islam has negotiated its departure from Douma with the regime and Russia, demonstrating the success of this tactic.

On the basis of this overall assessment and on the intelligence collected by our services, and in the absence to date of chemical samples analysed by our own laboratories, France therefore considers (i) that, beyond possible doubt, a chemical attack was carried out against civilians at Douma on 7 April 2018; and (ii) that there is no plausible scenario other than that of an attack by Syrian armed forces as part of a wider offensive in the Eastern Ghouta enclave. The Syrian armed and security forces are also considered to be responsible for other actions in the region as part of this same offensive in 2017 and 2018. Russia has undeniably provided active military support to the operations to seize back Ghouta. It has, moreover, provided constant political cover to the Syrian regime over the employment of chemical weapons, both at the UN Security Council and at the OPCW, despite conclusions to the contrary by the JIM.

This assessment will be updated as we collect new information.

7

The re-emergence of monkeypox in Nigeria after a nearly 40-year absence

Sunday, April 15th, 2018“…..In September 2017, the Nigeria Centre for Disease Control (NCDC) was notified of an 11-year-old boy with monkeypox. The source of the disease was unclear, though the boy and 2 of his siblings had played with a neighbor’s monkey (which was not ill). A total of 5 other members of the index patient’s household developed similar symptoms……”

Key facts

- Monkeypox is a rare disease that occurs primarily in remote parts of Central and West Africa, near tropical rainforests.

- The monkeypox virus can cause a fatal illness in humans and, although it is similar to human smallpox which has been eradicated, it is much milder.

- The monkeypox virus is transmitted to people from various wild animals but has limited secondary spread through human-to-human transmission.

- Typically, case fatality in monkeypox outbreaks has been between 1% and 10%, with most deaths occurring in younger age groups.

- There is no treatment or vaccine available although prior smallpox vaccination was highly effective in preventing monkeypox as well.

Monkeypox is a rare viral zoonosis (a virus transmitted to humans from animals) with symptoms in humans similar to those seen in the past in smallpox patients, although less severe. Smallpox was eradicated in 1980.However, monkeypox still occurs sporadically in some parts of Africa.

Monkeypox is a member of the Orthopoxvirus genus in the family Poxviridae.

The virus was first identified in the State Serum Institute in Copenhagen, Denmark, in 1958 during an investigation into a pox-like disease among monkeys.

Outbreaks

Human monkeypox was first identified in humans in 1970 in the Democratic Republic of Congo (then known as Zaire) in a 9 year old boy in a region where smallpox had been eliminated in 1968. Since then, the majority of cases have been reported in rural, rainforest regions of the Congo Basin and western Africa, particularly in the Democratic Republic of Congo, where it is considered to be endemic. In 1996-97, a major outbreak occurred in the Democratic Republic of Congo.

In the spring of 2003, monkeypox cases were confirmed in the Midwest of the United States of America, marking the first reported occurrence of the disease outside of the African continent. Most of the patients had had close contact with pet prairie dogs.

In 2005, a monkeypox outbreak occurred in Unity, Sudan and sporadic cases have been reported from other parts of Africa. In 2009, an outreach campaign among refugees from the Democratic Republic of Congo into the Republic of Congo identified and confirmed two cases of monkeypox. Between August and October 2016, a monkeypox outbreak in the Central African Republic was contained with 26 cases and two deaths.

Transmission

Infection of index cases results from direct contact with the blood, bodily fluids, or cutaneous or mucosal lesions of infected animals. In Africa human infections have been documented through the handling of infected monkeys, Gambian giant rats and squirrels, with rodents being the major reservoir of the virus. Eating inadequately cooked meat of infected animals is a possible risk factor.

Secondary, or human-to-human, transmission can result from close contact with infected respiratory tract secretions, skin lesions of an infected person or objects recently contaminated by patient fluids or lesion materials. Transmission occurs primarily via droplet respiratory particles usually requiring prolonged face-to-face contact, which puts household members of active cases at greater risk of infection. Transmission can also occur by inoculation or via the placenta (congenital monkeypox). There is no evidence, to date, that person-to-person transmission alone can sustain monkeypox infections in the human population.

In recent animal studies of the prairie dog-human monkeypox model, two distinct clades of the virus were identified – the Congo Basin and the West African clades – with the former found to be more virulent.

Signs and symptoms

The incubation period (interval from infection to onset of symptoms) of monkeypox is usually from 6 to 16 days but can range from 5 to 21 days.

The infection can be divided into two periods:

- the invasion period (0-5 days) characterized by fever, intense headache, lymphadenopathy (swelling of the lymph node), back pain, myalgia (muscle ache) and an intense asthenia (lack of energy);

- the skin eruption period (within 1-3 days after appearance of fever) where the various stages of the rash appears, often beginning on the face and then spreading elsewhere on the body. The face (in 95% of cases), and palms of the hands and soles of the feet (75%) are most affected. Evolution of the rash from maculopapules (lesions with a flat bases) to vesicles (small fluid-filled blisters), pustules, followed by crusts occurs in approximately 10 days. Three weeks might be necessary before the complete disappearance of the crusts.

The number of the lesions varies from a few to several thousand, affecting oral mucous membranes (in 70% of cases), genitalia (30%), and conjunctivae (eyelid) (20%), as well as the cornea (eyeball).

Some patients develop severe lymphadenopathy (swollen lymph nodes) before the appearance of the rash, which is a distinctive feature of monkeypox compared to other similar diseases.

Monkeypox is usually a self-limited disease with the symptoms lasting from 14 to 21 days. Severe cases occur more commonly among children and are related to the extent of virus exposure, patient health status and severity of complications.

People living in or near the forested areas may have indirect or low-level exposure to infected animals, possibly leading to subclinical (asymptomatic) infection.

The case fatality has varied widely between epidemics but has been less than 10% in documented events, mostly among young children. In general, younger age-groups appear to be more susceptible to monkeypox.

Diagnosis

The differential diagnoses that must be considered include other rash illnesses, such as, smallpox, chickenpox, measles, bacterial skin infections, scabies, syphilis, and medication-associated allergies. Lymphadenopathy during the prodromal stage of illness can be a clinical feature to distinguish it from smallpox.

Monkeypox can only be diagnosed definitively in the laboratory where the virus can be identified by a number of different tests:

- enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA)

- antigen detection tests

- polymerase chain reaction (PCR) assay

- virus isolation by cell culture

Treatment and vaccine

There are no specific treatments or vaccines available for monkeypox infection, but outbreaks can be controlled. Vaccination against smallpox has been proven to be 85% effective in preventing monkeypox in the past but the vaccine is no longer available to the general public after it was discontinued following global smallpox eradication. Nevertheless, prior smallpox vaccination will likely result in a milder disease course.

Natural host of monkeypox virus

In Africa, monkeypox infection has been found in many animal species: rope squirrels, tree squirrels, Gambian rats, striped mice, dormice and primates. Doubts persist on the natural history of the virus and further studies are needed to identify the exact reservoir of the monkeypox virus and how it is maintained in nature.

In the USA, the virus is thought to have been transmitted from African animals to a number of susceptible non-African species (like prairie dogs) with which they were co-housed.

Prevention

Preventing monkeypox expansion through restrictions on animal trade

Restricting or banning the movement of small African mammals and monkeys may be effective in slowing the expansion of the virus outside Africa.

Captive animals should not be inoculated against smallpox. Instead, potentially infected animals should be isolated from other animals and placed into immediate quarantine. Any animals that might have come into contact with an infected animal should be quarantined, handled with standard precautions and observed for monkeypox symptoms for 30 days.

Reducing the risk of infection in people

During human monkeypox outbreaks, close contact with other patients is the most significant risk factor for monkeypox virus infection. In the absence of specific treatment or vaccine, the only way to reduce infection in people is by raising awareness of the risk factors and educating people about the measures they can take to reduce exposure to the virus. Surveillance measures and rapid identification of new cases is critical for outbreak containment.

Public health educational messages should focus on the following risks:

- Reducing the risk of human-to-human transmission. Close physical contact with monkeypox infected people should be avoided. Gloves and protective equipment should be worn when taking care of ill people. Regular hand washing should be carried out after caring for or visiting sick people.

- Reducing the risk of animal-to-human transmission. Efforts to prevent transmission in endemic regions should focus on thoroughly cooking all animal products (blood, meat) before eating. Gloves and other appropriate protective clothing should be worn while handling sick animals or their infected tissues, and during slaughtering procedures.

Controlling infection in health-care settings

Health-care workers caring for patients with suspected or confirmed monkeypox virus infection, or handling specimens from them, should implement standard infection control precautions.

Healthcare workers and those treating or exposed to patients with monkeypox or their samples should consider being immunized against smallpox via their national health authorities. Older smallpox vaccines should not be administered to people with comprised immune systems.

Samples taken from people and animals with suspected monkeypox virus infection should be handled by trained staff working in suitably equipped laboratories.

WHO response

WHO supports Member States with surveillance, preparedness and outbreak response activities in affected countries.

April 14, 1912: Just before midnight in the North Atlantic, the RMS Titanic hits an iceberg and begins to sink.

Saturday, April 14th, 20182017-2018 Influenza Season Week 14 ending April 7, 2018

Saturday, April 14th, 2018Synopsis:

During week 14 (April 1-7, 2018), influenza activity decreased in the United States.

- Viral Surveillance: Overall, influenza A(H3) viruses have predominated this season. Since early March, influenza B viruses have been more frequently reported than influenza A viruses. The percentage of respiratory specimens testing positive for influenza in clinical laboratories decreased.

- Pneumonia and Influenza Mortality: The proportion of deaths attributed to pneumonia and influenza (P&I) was below the system-specific epidemic threshold in the National Center for Health Statistics (NCHS) Mortality Surveillance System.

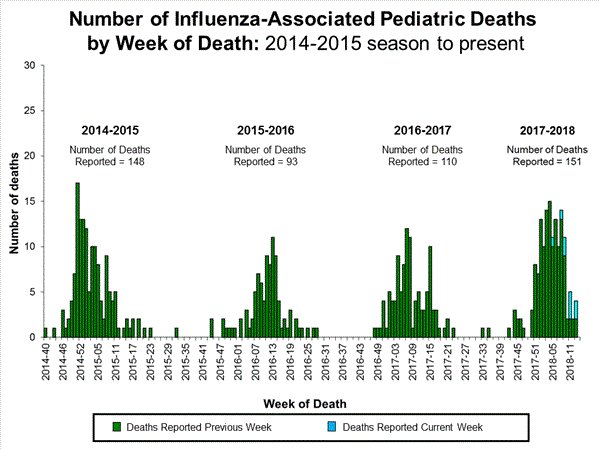

- Influenza-associated Pediatric Deaths: Nine influenza-associated pediatric deaths were reported.

- Influenza-associated Hospitalizations: A cumulative rate of 101.6 laboratory-confirmed influenza-associated hospitalizations per 100,000 population was reported.

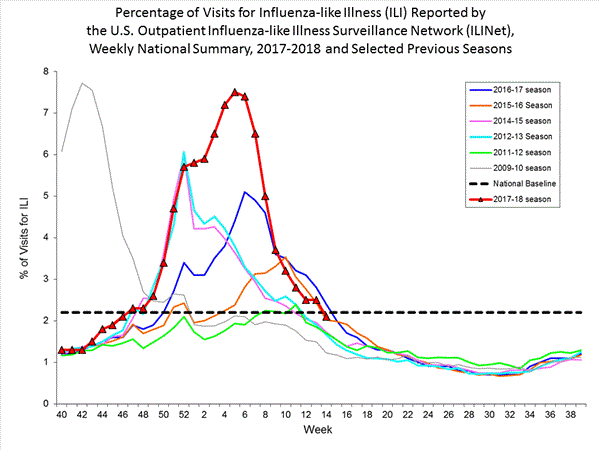

- Outpatient Illness Surveillance: The proportion of outpatient visits for influenza-like illness (ILI) was 2.1%, which is below the national baseline of 2.2%. Six of 10 regions reported ILI at or above region-specific baseline levels. Two states experienced high ILI activity; two states experienced moderate ILI activity; 11 states experienced low ILI activity; and New York City, the District of Columbia, Puerto Rico, and 35 states experienced minimal ILI activity.

- Geographic Spread of Influenza: The geographic spread of influenza in seven states was reported as widespread; Guam, Puerto Rico and 22 states reported regional activity; the District of Columbia and 16 states reported local activity; and the U.S. Virgin Islands and five states reported sporadic activity.