Archive for February, 2019

2018-2019 Influenza Season Week 7 ending February 16, 2019: Influenza activity continues to increase in the United States.

Saturday, February 23rd, 20192018-2019 U.S. Flu Season: Preliminary Burden Estimates from October 1, 2018, through February 16, 2019

Saturday, February 23rd, 2019CCDC estimates that, from , there have been:

CDC

* 17.7 million – 20.4 million flu illnesses

![]()

- 8.2 million – 9.6 million flu medical visits

- 214,000 – 256,000 flu hospitalizations

- 13,600 – 22,300 flu deaths

U.S.: Infectious Diseases Occurring in Workplaces

Saturday, February 23rd, 2019Su C, de Perio MA, Cummings KJ, McCague A, Luckhaupt SE, Sweeney M. Case Investigations of Infectious Diseases Occurring in Workplaces, United States, 2006–2015. Emerg Infect Dis. 2019;25(3):397-405. https://dx.doi.org/10.3201/eid2503.180708

Reported case investigations of infectious disease occurring in workplaces, by industry categories, occupations, and diseases, United States, 2006–2015*

| Industry category (NAICS code) | Occupations | Infectious diseases | References† |

|---|---|---|---|

| Agriculture, forestry, fishing, and hunting (11) | Hunter | Brucellosis | (61) |

| Farmer | Variant influenza A(H3N2); Escherichia coli infection | (83); (71) | |

|

|

Rodent breeder

|

LCMV infection

|

(82)

|

| Construction (23)

|

Laborer

|

Coccidioidomycosis

|

(23,25)

|

| Manufacturing (31–33) | Drum maker | Anthrax | (2) |

| Poultry vaccine production worker | Salmonellosis | (29) | |

| Poultry-processing worker | Campylobacteriosis | (17) | |

| Furniture company worker | Tuberculosis | (54) | |

| Slaughterhouse inspector | Q fever | (65) | |

|

|

Automobile manufacturing worker

|

Legionnaires’ disease

|

(81)

|

| Transportation (48) | Truck driver | Streptococcus suis infection; cryptosporidiosis | (79); (88) |

|

|

Pilot, flight attendant

|

Malaria

|

(37)

|

| Professional, scientific, and technical services (54)

|

Laboratory worker

|

Vaccinia virus infection, HIV infection, plague, cowpox, meningococcal disease, brucellosis

|

(13,30–35,86)

|

| Administrative support and waste management and remediation services (56)

|

Landscaper

|

Tularemia

|

(21)

|

| Education services (61)

|

School employee, teacher

|

Influenza

|

(8)

|

| Healthcare and social assistance (62) | Healthcare worker (security guard, nurse, nursing aide, physician, volunteer, environmental services) | Mumps; MRSA skin infection; norovirus gastroenteritis; adenovirus 14 infection; RSV infection; Trichophyton tonsurans skin infection; meningococcal disease; influenza; salmonellosis; Ebola virus disease; measles; TB | (51); (52); (56); (57); (62); (64); (66); (11,68); (87); (14); (92); (12,77) |

|

|

Childcare worker

|

E. coli infection

|

(72)

|

| Arts, entertainment, and recreation (71) | Wildlife biologist | Plague | (59) |

| Animal caretaker | MRSA skin infection | (63) | |

| Adult film performer | HIV infection | (36) | |

| Spa maintenance worker | MAC infection | (22) | |

| Filmmaker | Coccidioidomycosis | (24) | |

|

|

Day camp counselor

|

Histoplasmosis

|

(26)

|

| Food services (72)

|

Cook, food server

|

Norovirus gastroenteritis; salmonellosis; E. coli infection

|

(20); (19);

(89)

|

| Other services except public administration (81) | Embalmer | TB | (16) |

| Animal refugee worker | Tuberculosis; sealpox virus infection | (28); (18) | |

| Pet store worker | Salmonellosis | (74) | |

|

|

Missionary worker

|

Melioidosis; dengue fever

|

(75); (70)

|

| Public administration (92) | US Customs officer | Measles | (9,10) |

| Police officer | Meningococcal disease | (66) | |

| Firefighter | Cryptosporidiosis | (88) | |

| Correctional officer | Cryptosporidiosis; Shiga toxin–producing E. coli infection; TB; coccidioidomycosis; | (78); (71); (12); (90) | |

| Military | Legionellosis; TB | (73); (53) |

*An expanded version of this table showing complete details on all cases is available online (https://wwwnc.cdc.gov/EID/article/25/3/18-0708-T1.htm). HIV, human immunodeficiency virus; LCMV, lymphocytic choriomeningitis virus; MAC, Mycobacterium avium complex; MRSA, methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus; RSV, respiratory syncytial virus; TB, tuberculosis. NAICS, 2012 North American Industry Classification System (https://www.census.gov/eos/www/naics/).

†Reference numbers >50 and additional details on the literature search are available in the Appendix.

Holocaust in a bazaar in Dhaka

Friday, February 22nd, 2019“…..A car powered by compressed natural gas was traveling through a bazaar in Dhaka, Bangladesh’s capital, when the cylinder stored in the back exploded…..

The blast flipped the car. It then ignited several other cylinders that were being used at a street-side restaurant. Then a plastics store on the ground floor of a nearby building caught fire. Then a small shop that was illegally storing chemicals burst into flames.

A wall of fire surged across the street, engulfing bicycles, rickshaws, cars, people, everything in its path. The inferno claimed at least 70 lives….”

Hypothermia and Death in the U.S.

Friday, February 22nd, 2019QuickStats: Death Rates Attributed to Excessive Cold or Hypothermia Among Persons Aged ≥15 Years, by Urbanization Level and Age Group — National Vital Statistics System, 2015–2017. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2019;68:187. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.15585/mmwr.mm6807a8.

“…..During 2015–2017, death rates attributed to excessive cold or hypothermia increased steadily with age among those aged ≥15 years in both metropolitan and nonmetropolitan counties. The rate for persons aged ≥85 years reached 3.8 deaths per 100,000 in metropolitan counties and 7.3 in nonmetropolitan counties. The lowest rates were among those aged 15–24 years (0.2 in metropolitan counties and 0.5 in nonmetropolitan counties). In each age category, death rates were lower in metropolitan counties and higher in nonmetropolitan counties.

Source: National Center for Health Statistics, National Vital Statistics System, Mortality Data 2015–2017……”

Enteroinvasive Escherichia coli Outbreak Associated at a Potluck in North Carolina

Friday, February 22nd, 2019Herzig CT, Fleischauer AT, Lackey B, et al. Notes from the Field: Enteroinvasive Escherichia coli Outbreak Associated with a Potluck Party — North Carolina, June–July 2018. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2019;68:183–184. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.15585/mmwr.mm6807a5.

“On July 2, 2018, the North Carolina Division of Public Health was notified that approximately three dozen members of an ethnic Nepali refugee community had been transported to area hospitals for severe gastrointestinal illness after attending a potluck party on June 30. The North Carolina Division of Public Health partnered with the local health department and CDC to investigate the outbreak, identify the cause, and prevent further transmission. The investigation included molecular-guided laboratory testing of clinical specimens by CDC, which determined that this was the first confirmed U.S. outbreak of enteroinvasive Escherichia coli (EIEC) in 47 years.

A case was defined as the occurrence of diarrhea, vomiting, or fever ≥101°F (38.3°C) in a person who consumed food served at the party. Cases were identified through medical record review and retrospective cohort investigation with convenience sampling of party attendees. Among approximately 100 attendees, 52 met the case definition. Median age was 31 years (range = 3–76 years); 28 (54%) were hospitalized, including 13 (25%) with sepsis, and eight (15%) who were admitted to an intensive care unit. All patients recovered, and no secondary cases were identified.

Forty-nine persons, including 35 who were ill, were interviewed using a questionnaire to ascertain symptoms, recent travel, and food exposures. Participants also were provided with hand hygiene guidance. Among the 35 ill persons, 30 (86%) reported symptom onset on July 1, the day after the event (Figure). Median interval between eating and symptom onset was 20.5 hours (range = 1–45.5 hours). Overall, 33 (94%) ill persons experienced diarrhea, including 27 (77%), 19 (54%), and two (6%) who reported diarrhea that was watery, mucoid, or bloody, respectively. Thirty-two (91%) ill persons reported fever.

Participants reported eating chicken curry, vegetable curry, rice, lentil soup, fried bread, cold and hot salads, and cake; no imported foods were reported. No single food item was statistically significantly associated with illness; however, 37 persons reported eating chicken curry, and those who did had a 47% higher risk for illness than those who did not (risk ratio = 1.47; 95% confidence interval = 0.76–2.83). No food was available for testing…..”

Social Media Reactions to an Errant Warning of a Ballistic Missile Threat

Friday, February 22nd, 2019Murthy BP, Krishna N, Jones T, Wolkin A, Avchen RN, Vagi SJ. Public Health Emergency Risk Communication and Social Media Reactions to an Errant Warning of a Ballistic Missile Threat — Hawaii, January 2018. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2019;68:174–176. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.15585/mmwr.mm6807a2.

“……A total of 127,125 tweets were identified; after excluding 69,151 (54%) retweets and 43,444 (34%) quote tweets, 14,530 (11%) initial tweets remained for analysis. Among these, 5,880 (40%) were sent during the early period, and 8,650 (60%) were sent during the late period……”

* 8:07–8:45 a.m. Hawaii Standard Time.

† 8:46–9:24 a.m. Hawaii Standard Time (additional themes identified in addition to those in the early period).

What is already known about this topic?

Social media platforms are widely used to share information and disseminate alerts and warnings.

What is added by this report?

After an errant ballistic missile alert, social media reactions revealed how the public interprets, shares, and responds to information during an evolving threat. This knowledge can guide emergency risk communicators to develop timely and effective social media messages than can protect lives.

What are the implications for public health practice?

Social media can be an effective tool to send urgent messages during a public health emergency. Public health practitioners need to improve messaging during emergency risk communications to address the public’s needs during each phase of an unfolding crisis to protect and save lives

Ontario, Canada: Listeria monocytogenes Associated with Pasteurized Chocolate Milk

Friday, February 22nd, 2019Hanson H, Whitfield Y, Lee C, Badiani T, Minielly C, Fenik J, et al. Listeria monocytogenes Associated with Pasteurized Chocolate Milk, Ontario, Canada. Emerg Infect Dis. 2019;25(3):581-584. https://dx.doi.org/10.3201/eid2503.180742

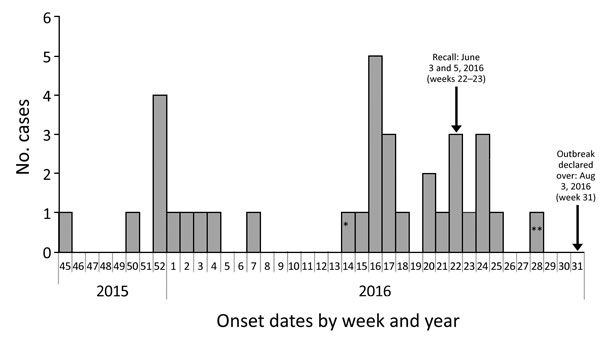

Figure 1. Outbreak cases of listeriosis (n = 34) by onset week and year, Ontario, Canada, November 2015–August 2016. Data were obtained from the Ontario Ministry of Health and Long-Term Care, integrated Public Health Information System database, extracted by Public Health Ontario, August 16, 2016. Weeks are defined according to the Public Health Agency of Canada epidemiologic week calendar. *Neonatal case-patient with symptom onset on April 4, 2016 (week 14), and illness most likely caused by mother-to-child transmission. **Asymptomatic case-patient from whom a specimen was collected on July 13, 2016, and exposure occurred before June 27, 2016 (week 28).

Figure 2. Bags of pasteurized chocolate milk as sold in Canada, with outer bag containing brand information removed. A bag of milk similar to these, found at the home of 1 case-patient during investigation of an outbreak of Listeria monocytogenes infection associated with pasteurized chocolate milk in Ontario, Canada, was found to be contaminated with the same strain obtained from infected patients.

Sunscreen: How to Help Protect Your Skin from the Sun

Friday, February 22nd, 2019What’s New

FDA regulates sunscreens to ensure they meet safety and effectiveness standards. To improve the quality, safety, and effectiveness of sunscreens, FDA issued a proposed rule on February 21, 2019 that describes updated proposed requirements for sunscreens. Given the recognized public health benefits of sunscreen use, Americans should continue to use sunscreen with other sun protective measures as this important rulemaking effort moves forward.

Additional information

Press Release

Infographic

Industry Fact Sheet

Consumer Update

Proposed rule

As an FDA-regulated product, sunscreens must pass certain tests before they are sold. But how you use this product, and what other protective measures you take, make a difference in how well you are able to protect yourself and your family from sunburn, skin cancer, early skin aging and other risks of overexposure to the sun. Some key sun safety tips include:

- Limit time in the sun, especially between the hours of 10 a.m. and 2 p.m., when the sun’s rays are most intense.

- Wear clothing to cover skin exposed to the sun, such as long-sleeved shirts, pants, sunglasses, and broad-brimmed hats.

- Use broad spectrum sunscreens with SPF values of 15 or higher regularly and as directed.

- Reapply sunscreen at least every two hours, and more often if you’re sweating or jumping in and out of the water.

Contents

Learn more about:

Read: Tips to Stay Safe in the Sun: From Sunscreen to Sunglasses

Watch: Videos about sunscreen

Learn: FDA Basics: Practice the art of sun protection

How to apply and store sunscreen

- Apply 15 minutes before you go outside. This allows the sunscreen (of SPF 15 or higher) to have enough time to provide the maximum benefit.

- Use enough to cover your entire face and body (avoiding the eyes and mouth). An average-sized adult or child needs at least one ounce of sunscreen (about the amount it takes to fill a shot glass) to evenly cover the body from head to toe.

Frequently forgotten spots:

Ears

Nose

Lips

Back of neck

Hands

Tops of feet

Along the hairline

Areas of the head exposed by balding or thinning hair

- Know your skin. Fair-skinned people are likely to absorb more solar energy than dark-skinned people under the same conditions.

- Reapply at least every two hours, and more often if you’re swimming or sweating.

There’s no such thing as waterproof sunscreen

People should also be aware that no sunscreens are “waterproof.” All sunscreens eventually wash off. Sunscreens labeled “water resistant” are required to be tested according to the required SPF test procedure. The labels are required to state whether the sunscreen remains effective for 40 minutes or 80 minutes when swimming or sweating, and all sunscreens must provide directions on when to reapply.

Storing your sunscreen

To keep your sunscreen in good condition, the FDA recommends that sunscreen containers should not be exposed to direct sun. Protect the sunscreen by wrapping the containers in towels or keeping them in the shade. Sunscreen containers can also be kept in coolers while outside in the heat for long periods of time. This is why all sunscreen labels must say: “Protect the product in this container from excessive heat and direct sun.”

Read: Tips to Stay Safe in the Sun: From Sunscreen to Sunglasses

Watch: Videos about sunscreen

Sunscreens for infants and children

Sunscreens are not recommended for infants. The FDA recommends that infants be kept out of the sun during the hours of 10 a.m. and 2 p.m., and to use protective clothing if they have to be in the sun. Infants are at greater risk than adults of sunscreen side effects, such as a rash. The best protection for infants is to keep them out of the sun entirely. Ask a doctor before applying sunscreen to children under six months of age.

For children over the age of six months, the FDA recommends using sunscreen as directed on the Drug Facts label.

Read: Should You Put Sunscreen on Infants? Not Usually.

Types of sunscreen

Sunscreen comes in many forms, including:

Lotions

Creams

Sticks

Gels

Oils

Butters

Pastes

Sprays

The directions for using sunscreen products can vary according to their forms. For example, spray sunscreens should never be applied directly to your face. This is just one reason why you should always read the label before using a sunscreen product.

Note: FDA has not authorized the marketing of nonprescription sunscreen products in the form of wipes, towelettes, powders, body washes, or shampoos.

Read: Use Sunscreen Spray? Avoid Open Flame.

Understanding the sunscreen label

Broad spectrum

Not all sunscreens are broad spectrum, so it is important to look for it on the label. Broad spectrum sunscreen provides protection from the sun’s ultraviolet (UV) radiation. There are two types of UV radiation that you need to protect yourself from – UVA and UVB. Broad spectrum provides protection against both by providing a chemical barrier that absorbs or reflects UV radiation before it can damage the skin.

Sunscreens that are not broad spectrum or that lack an SPF of at least 15 must carry the warning:

Sun protection factor (SPF)

Sunscreens are made in a wide range of SPFs.

The SPF value indicates the level of sunburn protection provided by the sunscreen product. All sunscreens are tested to measure the amount of UV radiation exposure it takes to cause sunburn when using a sunscreen compared to how much UV exposure it takes to cause a sunburn when not using a sunscreen. The product is then labeled with the appropriate SPF value. Higher SPF values (up to 50) provide greater sunburn protection. Because SPF values are determined from a test that measures protection against sunburn caused by UVB radiation, SPF values only indicate a sunscreen’s UVB protection.

As of June 2011, sunscreens that pass the broad spectrum test can demonstrate that they also provide UVA protection. Therefore, under the label requirements, for sunscreens labeled “Broad Spectrum SPF [value]”, they will indicate protection from both UVA and UVB radiation.

To get the most protection out of sunscreen, choose one with an SPF of at least 15.

If your skin is fair, you may want a higher SPF of 30 to 50.

There is a popular misconception that SPF relates to time of solar exposure. For example, many people believe that, if they normally get sunburned in one hour, then an SPF 15 sunscreen allows them to stay in the sun for 15 hours (e.g., 15 times longer) without getting sunburn. This is not true because SPF is not directly related to time of solar exposure but to amount of solar exposure.

The sun is stronger in the middle of the day compared to early morning and early evening hours. That means your risk of sunburn is higher at mid-day. Solar intensity is also related to geographic location, with greater solar intensity occurring at lower latitudes.

Sunscreen ingredients

Every drug has active ingredients and inactive ingredients. In the case of sunscreen, active ingredients are the ones that are protecting your skin from the sun’s harmful UV rays. Inactive ingredients are all other ingredients that are not active ingredients, such as water or oil that may be used in formulating sunscreens. Below is a list of acceptable active ingredients in products that are labeled as sunscreen:

Aminobenzoic acid

Avobenzone

Cinoxate

Dioxybenzone

Homosalate

Meradimate

Octocrylene

Octinoxate

Octisalate

Oxybenzone

Padimate O

Ensulizole

Sulisobenzone

Titanium dioxide

Trolamine salicylate

Zinc oxide

Although the protective action of sunscreen products takes place on the surface of the skin, there is evidence that at least some sunscreen active ingredients may be absorbed through the skin and enter the body. This makes it important to perform studies to determine whether, and to what extent, use of sunscreen products as directed may result in unintended, chronic, systemic exposure to sunscreen active ingredients.

Sunscreen expiration dates

FDA regulations require all sunscreens and other nonprescription drugs to have an expiration date unless stability testing conducted by the manufacturer has shown that the product will remain stable for at least three years. That means, a sunscreen product that doesn’t have an expiration date should be considered expired three years after purchase.

To make sure that your sunscreen is providing the sun protection promised in its labeling, the FDA recommends that you do not use sunscreen products that have passed their expiration date (if there is one), or that have no expiration date and were not purchased within the last three years. Expired sunscreens should be discarded because there is no assurance that they remain safe and fully effective.

Read: Don’t Be Tempted to Use Expired Medicine

Read: How to dispose of the outdated drugs

Sunscreens from other countries

In Europe and in some other countries, sunscreens are regulated as cosmetics, not as drugs, and are subject to different marketing requirements. Any sunscreen sold in the United States is regulated as a drug because it makes a drug claim – to help prevent sunburn or to decrease the risks of skin cancer and early skin aging caused by the sun.

If you purchase a sunscreen outside the United States, it is important to read the label to understand the instructions for use and any potential differences between the product and U.S. products.

Read: From our perspective: Helping to ensure the safety and effectiveness of sunscreens

Learn: FDA’s sunscreen guidance outlines safety and effectiveness data recommended for additional active ingredients

Additional Consumer Information

- Don’t Fry Day (the Friday before Memorial Day)

Protect your skin while enjoying the outdoors - CDC Sun Safety

- Skin Cancer Screening

- TanningThis site is intended to provide a source of general information on skin tanning, ultraviolet (UV) exposure, UV emitting products, and skin protection.

Regulatory Information

- Sunscreen Innovation Act

- Rulemaking History for monograph sunscreensRulemaking History for OTC Sunscreen Drug Products

- Questions and answers from 2011 labelling changes