Archive for the ‘Climate Change’ Category

NEJM: Climate Change — A Health Emergency

Monday, January 28th, 2019Climate Change — A Health Emergency

Caren G. Solomon, M.D., M.P.H., and Regina C. LaRocque, M.D., M.P.H.

January 17, 2019

N Engl J Med 2019; 380:209-211

DOI: 10.1056/NEJMp1817067

“…..Camp Wildfire spread rapidly in California in early November 2018….[T]he chaos began. Within the next 24 hours, with fires raging, 12 new burn patients were rushed to his facility (which usually admits 1 or 2 patients in a given day). The most severely injured man had burns over nearly half his body, with exposed bone and tendon; a month later, he and two other patients remained hospitalized, facing repeated surgeries. And these were the patients fortunate enough to have made it to the hospital. At least 85 people died and nearly 14,000 homes were lost in what is the largest California wildfire on record….”

Tuyuksu Glacier in Central Asia: In 6 decades it has lost more than 1/2 mile

Sunday, January 20th, 2019“….The world’s roughly 150,000 glaciers, not including the large ice sheets of Greenland and Antarctica, cover about 200,000 square miles of the earth’s surface. Over the last four decades they’ve lost the equivalent of a layer of ice 70 feet thick…..”

Explaining Extreme Events in 2017 from a Climate Perspective

Thursday, December 20th, 2018

Download by Chapter:

- Hydroclimatic Extremes as Challenges for the Water Management Community: Lessons from Oroville Dam and Hurricane Harvey

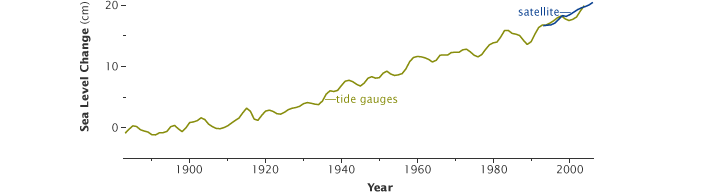

- Observations of the Rate and Acceleration of Global Mean Sea Level Change

- Anthropogenic Contributions to the Intensity of the 2017 United States Northern Great Plains Drought

- Attribution of the 2017 Northern High Plains Drought

- The Extremely Wet March of 2017 in Peru

- Contribution of Anthropogenic Climate Change to April–May 2017 Heavy Precipitation over the Uruguay River Basin

- December 2016: Linking the Lowest Arctic Sea-Ice Extent on Record with the Lowest European Precipitation Event on Record

- The Exceptional Summer Heat Wave in Southern Europe 2017

- Examining the Potential Contributions of Extreme “Western v” Sea Surface Temperatures to the 2017 March–June East African Drought

- Risks of Pre-Monsoon Extreme Rainfall Events of Bangladesh: Is Anthropogenic Climate Change Playing a Role?

- The Effects of Natural Variability and Climate Change on the Record Low Sunshine over Japan During August 2017

- Anthropogenic Contribution to the 2017 Earliest Summer Onset in South Korea

- Anthropogenic Influence on the Heaviest June Precipitation in Southeastern China Since 1961

- Attribution of the Persistent Spring–Summer Hot and Dry Extremes over Northeast China in 2017

- Anthropogenic Warming Has Substantially Increased the Likelihood of July 2017–like Heat Waves over Central Eastern China

- Attribution of a Record-Breaking Heatwave Event in Summer 2017 over the Yangtze River Delta

- The Role of Natural Variability and Anthropogenic Climate Change in the 2017/18 Tasman Sea Marine Heatwave

- On Determining the Impact of Increasing Atmospheric CO2 on the Record Fire Weather in Eastern Australia in February

The National Climate Assessment (NCA) assesses the science of climate change and variability and its impacts across the United States, now and throughout this century.

Monday, November 26th, 2018Fourth National Climate Change Report

FOURTH NATIONAL CLIMATE ASSESSMENT

Summary Findings

These Summary Findings represent a high-level synthesis of the material in the underlying report. The findings consolidate Key Messages and supporting evidence from 16 national-level topic chapters, 10 regional chapters, and 2 chapters that focus on societal response strategies (mitigation and adaptation). Unless otherwise noted, qualitative statements regarding future conditions in these Summary Findings are broadly applicable across the range of different levels of future climate change and associated impacts considered in this report.

1. Communities

Climate change creates new risks and exacerbates existing vulnerabilities in communities across the United States, presenting growing challenges to human health and safety, quality of life, and the rate of economic growth.

The impacts of climate change are already being felt in communities across the country. More frequent and intense extreme weather and climate-related events, as well as changes in average climate conditions, are expected to continue to damage infrastructure, ecosystems, and social systems that provide essential benefits to communities. Future climate change is expected to further disrupt many areas of life, exacerbating existing challenges to prosperity posed by aging and deteriorating infrastructure, stressed ecosystems, and economic inequality. Impacts within and across regions will not be distributed equally. People who are already vulnerable, including lower-income and other marginalized communities, have lower capacity to prepare for and cope with extreme weather and climate-related events and are expected to experience greater impacts. Prioritizing adaptation actions for the most vulnerable populations would contribute to a more equitable future within and across communities. Global action to significantly cut greenhouse gas emissions can substantially reduce climate-related risks and increase opportunities for these populations in the longer term.

2. Economy

Without substantial and sustained global mitigation and regional adaptation efforts, climate change is expected to cause growing losses to American infrastructure and property and impede the rate of economic growth over this century.

In the absence of significant global mitigation action and regional adaptation efforts, rising temperatures, sea level rise, and changes in extreme events are expected to increasingly disrupt and damage critical infrastructure and property, labor productivity, and the vitality of our communities. Regional economies and industries that depend on natural resources and favorable climate conditions, such as agriculture, tourism, and fisheries, are vulnerable to the growing impacts of climate change. Rising temperatures are projected to reduce the efficiency of power generation while increasing energy demands, resulting in higher electricity costs. The impacts of climate change beyond our borders are expected to increasingly affect our trade and economy, including import and export prices and U.S. businesses with overseas operations and supply chains. Some aspects of our economy may see slight near-term improvements in a modestly warmer world. However, the continued warming that is projected to occur without substantial and sustained reductions in global greenhouse gas emissions is expected to cause substantial net damage to the U.S. economy throughout this century, especially in the absence of increased adaptation efforts. With continued growth in emissions at historic rates, annual losses in some economic sectors are projected to reach hundreds of billions of dollars by the end of the century—more than the current gross domestic product (GDP) of many U.S. states.

3. Interconnected Impacts

Climate change affects the natural, built, and social systems we rely on individually and through their connections to one another. These interconnected systems are increasingly vulnerable to cascading impacts that are often difficult to predict, threatening essential services within and beyond the Nation’s borders.

Climate change presents added risks to interconnected systems that are already exposed to a range of stressors such as aging and deteriorating infrastructure, land-use changes, and population growth. Extreme weather and climate-related impacts on one system can result in increased risks or failures in other critical systems, including water resources, food production and distribution, energy and transportation, public health, international trade, and national security. The full extent of climate change risks to interconnected systems, many of which span regional and national boundaries, is often greater than the sum of risks to individual sectors. Failure to anticipate interconnected impacts can lead to missed opportunities for effectively managing the risks of climate change and can also lead to management responses that increase risks to other sectors and regions. Joint planning with stakeholders across sectors, regions, and jurisdictions can help identify critical risks arising from interaction among systems ahead of time.

4. Actions to Reduce Risks

Communities, governments, and businesses are working to reduce risks from and costs associated with climate change by taking action to lower greenhouse gas emissions and implement adaptation strategies. While mitigation and adaptation efforts have expanded substantially in the last four years, they do not yet approach the scale considered necessary to avoid substantial damages to the economy, environment, and human health over the coming decades.

Future risks from climate change depend primarily on decisions made today. The integration of climate risk into decision-making and the implementation of adaptation activities have significantly increased since the Third National Climate Assessment in 2014, including in areas of financial risk reporting, capital investment planning, development of engineering standards, military planning, and disaster risk management. Transformations in the energy sector—including the displacement of coal by natural gas and increased deployment of renewable energy—along with policy actions at the national, regional, state, and local levels are reducing greenhouse gas emissions in the United States. While these adaptation and mitigation measures can help reduce damages in a number of sectors, this assessment shows that more immediate and substantial global greenhouse gas emissions reductions, as well as regional adaptation efforts, would be needed to avoid the most severe consequences in the long term. Mitigation and adaptation actions also present opportunities for additional benefits that are often more immediate and localized, such as improving local air quality and economies through investments in infrastructure. Some benefits, such as restoring ecosystems and increasing community vitality, may be harder to quantify.

5. Water

The quality and quantity of water available for use by people and ecosystems across the country are being affected by climate change, increasing risks and costs to agriculture, energy production, industry, recreation, and the environment.

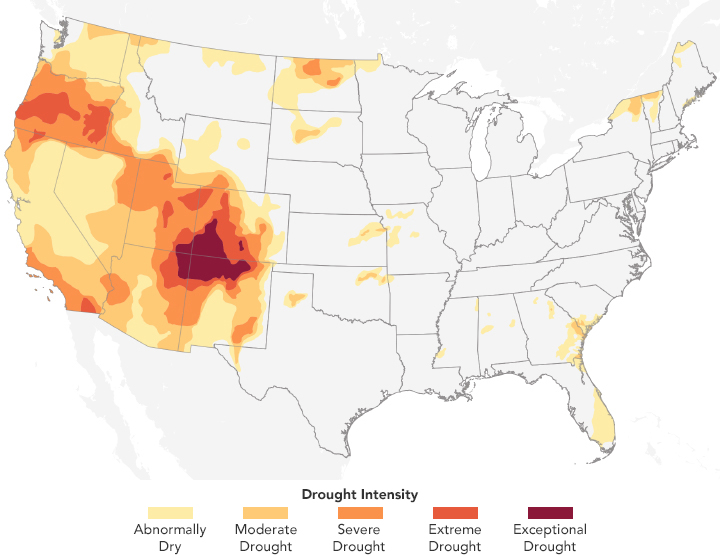

Rising air and water temperatures and changes in precipitation are intensifying droughts, increasing heavy downpours, reducing snowpack, and causing declines in surface water quality, with varying impacts across regions. Future warming will add to the stress on water supplies and adversely impact the availability of water in parts of the United States. Changes in the relative amounts and timing of snow and rainfall are leading to mismatches between water availability and needs in some regions, posing threats to, for example, the future reliability of hydropower production in the Southwest and the Northwest. Groundwater depletion is exacerbating drought risk in many parts of the United States, particularly in the Southwest and Southern Great Plains. Dependable and safe water supplies for U.S. Caribbean, Hawai‘i, and U.S.-Affiliated Pacific Island communities are threatened by drought, flooding, and saltwater contamination due to sea level rise. Most U.S. power plants rely on a steady supply of water for cooling, and operations are expected to be affected by changes in water availability and temperature increases. Aging and deteriorating water infrastructure, typically designed for past environmental conditions, compounds the climate risk faced by society. Water management strategies that account for changing climate conditions can help reduce present and future risks to water security, but implementation of such practices remains limited.

6. Health

Impacts from climate change on extreme weather and climate-related events, air quality, and the transmission of disease through insects and pests, food, and water increasingly threaten the health and well-being of the American people, particularly populations that are already vulnerable.

Changes in temperature and precipitation are increasing air quality and health risks from wildfire and ground-level ozone pollution. Rising air and water temperatures and more intense extreme events are expected to increase exposure to waterborne and foodborne diseases, affecting food and water safety. With continued warming, cold-related deaths are projected to decrease and heat-related deaths are projected to increase; in most regions, increases in heat-related deaths are expected to outpace reductions in cold-related deaths. The frequency and severity of allergic illnesses, including asthma and hay fever, are expected to increase as a result of a changing climate. Climate change is also projected to alter the geographic range and distribution of disease-carrying insects and pests, exposing more people to ticks that carry Lyme disease and mosquitoes that transmit viruses such as Zika, West Nile, and dengue, with varying impacts across regions. Communities in the Southeast, for example, are particularly vulnerable to the combined health impacts from vector-borne disease, heat, and flooding. Extreme weather and climate-related events can have lasting mental health consequences in affected communities, particularly if they result in degradation of livelihoods or community relocation. Populations including older adults, children, low-income communities, and some communities of color are often disproportionately affected by, and less resilient to, the health impacts of climate change. Adaptation and mitigation policies and programs that help individuals, communities, and states prepare for the risks of a changing climate reduce the number of injuries, illnesses, and deaths from climate-related health outcomes.

7. Indigenous Peoples

Climate change increasingly threatens Indigenous communities’ livelihoods, economies, health, and cultural identities by disrupting interconnected social, physical, and ecological systems.

Many Indigenous peoples are reliant on natural resources for their economic, cultural, and physical well-being and are often uniquely affected by climate change. The impacts of climate change on water, land, coastal areas, and other natural resources, as well as infrastructure and related services, are expected to increasingly disrupt Indigenous peoples’ livelihoods and economies, including agriculture and agroforestry, fishing, recreation, and tourism. Adverse impacts on subsistence activities have already been observed. As climate changes continue, adverse impacts on culturally significant species and resources are expected to result in negative physical and mental health effects. Throughout the United States, climate-related impacts are causing some Indigenous peoples to consider or actively pursue community relocation as an adaptation strategy, presenting challenges associated with maintaining cultural and community continuity. While economic, political, and infrastructure limitations may affect these communities’ ability to adapt, tightly knit social and cultural networks present opportunities to build community capacity and increase resilience. Many Indigenous peoples are taking steps to adapt to climate change impacts structured around self-determination and traditional knowledge, and some tribes are pursuing mitigation actions through development of renewable energy on tribal lands.

8. Ecosystems and Ecosystem Services

Ecosystems and the benefits they provide to society are being altered by climate change, and these impacts are projected to continue. Without substantial and sustained reductions in global greenhouse gas emissions, transformative impacts on some ecosystems will occur; some coral reef and sea ice ecosystems are already experiencing such transformational changes.

Many benefits provided by ecosystems and the environment, such as clean air and water, protection from coastal flooding, wood and fiber, crop pollination, hunting and fishing, tourism, cultural identities, and more will continue to be degraded by the impacts of climate change. Increasing wildfire frequency, changes in insect and disease outbreaks, and other stressors are expected to decrease the ability of U.S. forests to support economic activity, recreation, and subsistence activities. Climate change has already had observable impacts on biodiversity, ecosystems, and the benefits they provide to society. These impacts include the migration of native species to new areas and the spread of invasive species. Such changes are projected to continue, and without substantial and sustained reductions in global greenhouse gas emissions, extinctions and transformative impacts on some ecosystems cannot be avoided in the long term. Valued aspects of regional heritage and quality of life tied to ecosystems, wildlife, and outdoor recreation will change with the climate, and as a result, future generations can expect to experience and interact with the natural environment in ways that are different from today. Adaptation strategies, including prescribed burning to reduce fuel for wildfire, creation of safe havens for important species, and control of invasive species, are being implemented to address emerging impacts of climate change. While some targeted response actions are underway, many impacts, including losses of unique coral reef and sea ice ecosystems, can only be avoided by significantly reducing global emissions of carbon dioxide and other greenhouse gases.

9. Agriculture

Rising temperatures, extreme heat, drought, wildfire on rangelands, and heavy downpours are expected to increasingly disrupt agricultural productivity in the United States. Expected increases in challenges to livestock health, declines in crop yields and quality, and changes in extreme events in the United States and abroad threaten rural livelihoods, sustainable food security, and price stability.

Climate change presents numerous challenges to sustaining and enhancing crop productivity, livestock health, and the economic vitality of rural communities. While some regions (such as the Northern Great Plains) may see conditions conducive to expanded or alternative crop productivity over the next few decades, overall, yields from major U.S. crops are expected to decline as a consequence of increases in temperatures and possibly changes in water availability, soil erosion, and disease and pest outbreaks. Increases in temperatures during the growing season in the Midwest are projected to be the largest contributing factor to declines in the productivity of U.S. agriculture. Projected increases in extreme heat conditions are expected to lead to further heat stress for livestock, which can result in large economic losses for producers. Climate change is also expected to lead to large-scale shifts in the availability and prices of many agricultural products across the world, with corresponding impacts on U.S. agricultural producers and the U.S. economy. These changes threaten future gains in commodity crop production and put rural livelihoods at risk. Numerous adaptation strategies are available to cope with adverse impacts of climate variability and change on agricultural production. These include altering what is produced, modifying the inputs used for production, adopting new technologies, and adjusting management strategies. However, these strategies have limits under severe climate change impacts and would require sufficient long- and short-term investment in changing practices.

10. Infrastructure

Our Nation’s aging and deteriorating infrastructure is further stressed by increases in heavy precipitation events, coastal flooding, heat, wildfires, and other extreme events, as well as changes to average precipitation and temperature. Without adaptation, climate change will continue to degrade infrastructure performance over the rest of the century, with the potential for cascading impacts that threaten our economy, national security, essential services, and health and well-being.

Climate change and extreme weather events are expected to increasingly disrupt our Nation’s energy and transportation systems, threatening more frequent and longer-lasting power outages, fuel shortages, and service disruptions, with cascading impacts on other critical sectors. Infrastructure currently designed for historical climate conditions is more vulnerable to future weather extremes and climate change. The continued increase in the frequency and extent of high-tide flooding due to sea level rise threatens America’s trillion-dollar coastal property market and public infrastructure, with cascading impacts to the larger economy. In Alaska, rising temperatures and erosion are causing damage to buildings and coastal infrastructure that will be costly to repair or replace, particularly in rural areas; these impacts are expected to grow without adaptation. Expected increases in the severity and frequency of heavy precipitation events will affect inland infrastructure in every region, including access to roads, the viability of bridges, and the safety of pipelines. Flooding from heavy rainfall, storm surge, and rising high tides is expected to compound existing issues with aging infrastructure in the Northeast. Increased drought risk will threaten oil and gas drilling and refining, as well as electricity generation from power plants that rely on surface water for cooling. Forward-looking infrastructure design, planning, and operational measures and standards can reduce exposure and vulnerability to the impacts of climate change and reduce energy use while providing additional near-term benefits, including reductions in greenhouse gas emissions.

11. Oceans & Coasts

Coastal communities and the ecosystems that support them are increasingly threatened by the impacts of climate change. Without significant reductions in global greenhouse gas emissions and regional adaptation measures, many coastal regions will be transformed by the latter part of this century, with impacts affecting other regions and sectors. Even in a future with lower greenhouse gas emissions, many communities are expected to suffer financial impacts as chronic high-tide flooding leads to higher costs and lower property values.

Rising water temperatures, ocean acidification, retreating arctic sea ice, sea level rise, high-tide flooding, coastal erosion, higher storm surge, and heavier precipitation events threaten our oceans and coasts. These effects are projected to continue, putting ocean and marine species at risk, decreasing the productivity of certain fisheries, and threatening communities that rely on marine ecosystems for livelihoods and recreation, with particular impacts on fishing communities in Hawai‘i and the U.S.-Affiliated Pacific Islands, the U.S. Caribbean, and the Gulf of Mexico. Lasting damage to coastal property and infrastructure driven by sea level rise and storm surge is expected to lead to financial losses for individuals, businesses, and communities, with the Atlantic and Gulf Coasts facing above-average risks. Impacts on coastal energy and transportation infrastructure driven by sea level rise and storm surge have the potential for cascading costs and disruptions across the country. Even if significant emissions reductions occur, many of the effects from sea level rise over this centuryand particularly through mid-centuryare already locked in due to historical emissions, and many communities are already dealing with the consequences. Actions to plan for and adapt to more frequent, widespread, and severe coastal flooding, such as shoreline protection and conservation of coastal ecosystems, would decrease direct losses and cascading impacts on other sectors and parts of the country. More than half of the damages to coastal property are estimated to be avoidable through well-timed adaptation measures. Substantial and sustained reductions in global greenhouse gas emissions would also significantly reduce projected risks to fisheries and communities that rely on them.

12. Tourism and Recreation

Outdoor recreation, tourist economies, and quality of life are reliant on benefits provided by our natural environment that will be degraded by the impacts of climate change in many ways.

Climate change poses risks to seasonal and outdoor economies in communities across the United States, including impacts on economies centered around coral reef-based recreation, winter recreation, and inland water-based recreation. In turn, this affects the well-being of the people who make their living supporting these economies, including rural, coastal, and Indigenous communities. Projected increases in wildfire smoke events are expected to impair outdoor recreational activities and visibility in wilderness areas. Declines in snow and ice cover caused by warmer winter temperatures are expected to negatively impact the winter recreation industry in the Northwest, Northern Great Plains, and the Northeast. Some fish, birds, and mammals are expected to shift where they live as a result of climate change, with implications for hunting, fishing, and other wildlife-related activities. These and other climate-related impacts are expected to result in decreased tourism revenue in some places and, for some communities, loss of identity. While some new opportunities may emerge from these ecosystem changes, cultural identities and economic and recreational opportunities based around historical use of and interaction with species or natural resources in many areas are at risk. Proactive management strategies, such as the use of projected stream temperatures to set priorities for fish conservation, can help reduce disruptions to tourist economies and recreation.

The effects of climate change: Heat waves, wildfires, sea level rise, hurricanes, flooding, drought and shortages of clean water.

Tuesday, November 20th, 2018Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change: A world of worsening food shortages and wildfires, and a mass die-off of coral reefs as soon as 2040

Monday, October 15th, 2018Document: Global Warming of 1.5 Degrees Centigrade

IPCC PRESS RELEASE

8 October 2018

Summary for Policymakers of IPCC Special Report on Global Warming of 1.5ºC approved by governments

INCHEON, Republic of Korea, 8 Oct – Limiting global warming to 1.5ºC would require rapid, farreaching and unprecedented changes in all aspects of society, the IPCC said in a new assessment. With clear benefits to people and natural ecosystems, limiting global warming to 1.5ºC compared to 2ºC could go hand in hand with ensuring a more sustainable and equitable society, the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) said on Monday.

The Special Report on Global Warming of 1.5ºC was approved by the IPCC on Saturday in Incheon, Republic of Korea. It will be a key scientific input into the Katowice Climate Change Conference in Poland in December, when governments review the Paris Agreement to tackle climate change.

“With more than 6,000 scientific references cited and the dedicated contribution of thousands of expert and government reviewers worldwide, this important report testifies to the breadth and policy relevance of the IPCC,” said Hoesung Lee, Chair of the IPCC.

Ninety-one authors and review editors from 40 countries prepared the IPCC report in response to an invitation from the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC) when it adopted the Paris Agreement in 2015.

The report’s full name is Global Warming of 1.5°C, an IPCC special report on the impacts of global warming of 1.5°C above pre-industrial levels and related global greenhouse gas emission pathways, in the context of strengthening the global response to the threat of climate change, sustainable development, and efforts to eradicate poverty.

“One of the key messages that comes out very strongly from this report is that we are already seeing the consequences of 1°C of global warming through more extreme weather, rising sea levels and diminishing Arctic sea ice, among other changes,” said Panmao Zhai, Co-Chair of IPCC Working Group I.

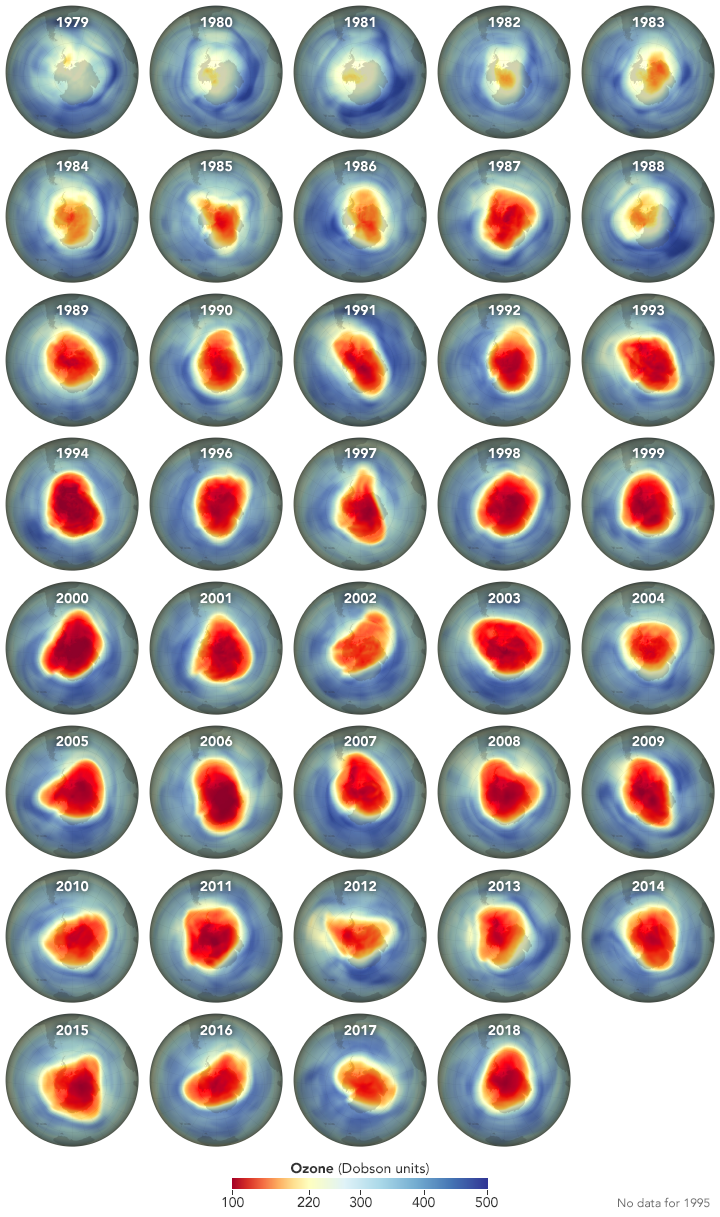

The report highlights a number of climate change impacts that could be avoided by limiting global warming to 1.5ºC compared to 2ºC, or more. For instance, by 2100, global sea level rise would be 10 cm lower with global warming of 1.5°C compared with 2°C. The likelihood of an Arctic Ocean free of sea ice in summer would be once per century with global warming of 1.5°C, compared with at least once per decade with 2°C. Coral reefs would decline by 70-90 percent with global warming of 1.5°C, whereas virtually all (> 99 percent) would be lost with 2ºC.

“Every extra bit of warming matters, especially since warming of 1.5ºC or higher increases the risk associated with long-lasting or irreversible changes, such as the loss of some ecosystems,” said Hans-Otto Pörtner, Co-Chair of IPCC Working Group II.

Limiting global warming would also give people and ecosystems more room to adapt and remain below relevant risk thresholds, added Pörtner. The report also examines pathways available to limit warming to 1.5ºC, what it would take to achieve them and what the consequences could be.

“The good news is that some of the kinds of actions that would be needed to limit global warming to 1.5ºC are already underway around the world, but they would need to accelerate,” said Valerie Masson-Delmotte, Co-Chair of Working Group I.

The report finds that limiting global warming to 1.5°C would require “rapid and far-reaching” transitions in land, energy, industry, buildings, transport, and cities. Global net human-caused emissions of carbon dioxide (CO2) would need to fall by about 45 percent from 2010 levels by 2030, reaching ‘net zero’ around 2050. This means that any remaining emissions would need to be balanced by removing CO2 from the air.

“Limiting warming to 1.5ºC is possible within the laws of chemistry and physics but doing so would require unprecedented changes,” said Jim Skea, Co-Chair of IPCC Working Group III.

Allowing the global temperature to temporarily exceed or ‘overshoot’ 1.5ºC would mean a greater reliance on techniques that remove CO2 from the air to return global temperature to below 1.5ºC by 2100. The effectiveness of such techniques are unproven at large scale and some may carry significant risks for sustainable development, the report notes.

“Limiting global warming to 1.5°C compared with 2°C would reduce challenging impacts on ecosystems, human health and well-being, making it easier to achieve the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals,” said Priyardarshi Shukla, Co-Chair of IPCC Working Group III.

The decisions we make today are critical in ensuring a safe and sustainable world for everyone, both now and in the future, said Debra Roberts, Co-Chair of IPCC Working Group II.

“This report gives policymakers and practitioners the information they need to make decisions that tackle climate change while considering local context and people’s needs. The next few years are probably the most important in our history,” she said.

The IPCC is the leading world body for assessing the science related to climate change, its impacts and potential future risks, and possible response options.

The report was prepared under the scientific leadership of all three IPCC working groups. Working Group I assesses the physical science basis of climate change; Working Group II addresses impacts, adaptation and vulnerability; and Working Group III deals with the mitigation of climate change.

The Paris Agreement adopted by 195 nations at the 21st Conference of the Parties to the UNFCCC in December 2015 included the aim of strengthening the global response to the threat of climate change by “holding the increase in the global average temperature to well below 2°C above preindustrial levels and pursuing efforts to limit the temperature increase to 1.5°C above pre-industrial levels.”

As part of the decision to adopt the Paris Agreement, the IPCC was invited to produce, in 2018, a Special Report on global warming of 1.5°C above pre-industrial levels and related global greenhouse gas emission pathways. The IPCC accepted the invitation, adding that the Special Report would look at these issues in the context of strengthening the global response to the threat of climate change, sustainable development, and efforts to eradicate poverty.

Global Warming of 1.5ºC is the first in a series of Special Reports to be produced in the IPCC’s Sixth Assessment Cycle. Next year the IPCC will release the Special Report on the Ocean and Cryosphere in a Changing Climate, and Climate Change and Land, which looks at how climate change affects land use.

– 3 –

The Summary for Policymakers (SPM) presents the key findings of the Special Report, based on the assessment of the available scientific, technical and socio-economic literature relevant to global warming of 1.5°C.

The Summary for Policymakers of the Special Report on Global Warming of 1.5ºC (SR15) is available at http://www.ipcc.ch/report/sr15/ or www.ipcc.ch.

Key statistics of the Special Report on Global Warming of 1.5ºC

91 authors from 44 citizenships and 40 countries of residence – 14 Coordinating Lead Authors (CLAs) – 60 Lead authors (LAs) – 17 Review Editors (REs) 133 Contributing authors (CAs) Over 6,000 cited references A total of 42,001 expert and government review comments (First Order Draft 12,895; Second Order Draft 25,476; Final Government Draft: 3,630)

For more information, contact: IPCC Press Office, Email: ipcc-media@wmo.int Werani Zabula +41 79 108 3157 or Nina Peeva +41 79 516 7068

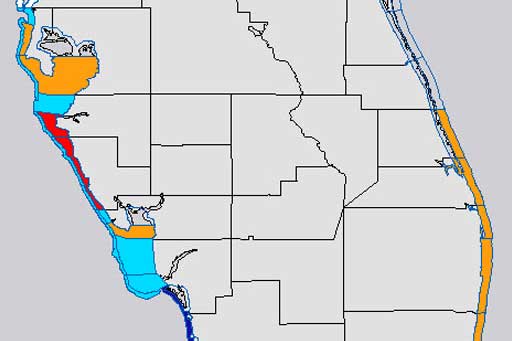

Red Tide & Florida: NOAA

Thursday, August 16th, 2018NEW: Summer 2018 Red Tide Event Affecting the West Coast of Florida

What is happening?

An unusually persistent harmful algal bloom (red tide) is currently affecting portions of the southwest coast of Florida. For the latest updates on this event, visit the Florida Fish and Wildlife Conservation Commission red tide status website or the NOAA Harmful Algal Bloom Bulletin.

How long will this red tide last?

If and when bloom the current bloom will end remains an open-ended question. Red tides can last as little as a few weeks or longer than a year. They can even subside and then reoccur. In 2005, for example, a bloom started off the coast of St. Petersburg, Florida, in January and then spread from there to Pensacola and Naples by October, persisting for the majority of the year. The duration of a bloom in nearshore Florida waters depends on physical and biological conditions that influence its growth and persistence, including sunlight, nutrients, and salinity, as well as the speed and direction of wind and water currents. Researchers are watching oceanographic conditions in the region carefully and using forecasting tools similar to seasonal weather forecasts to predict how long this bloom will last.

What is NOAA’s role in responding to this red tide event?

NOAA conducts scientific research and provides forecasts to give communities advance warnings to better deal with the adverse environmental impacts, health effects and economic losses associated with red tide and other harmful algal bloom events.

NOAA monitors conditions year round and provides official forecasts for red tide through two main products: conditions reports and bulletins. The conditions report identifies if red tide cell concentrations are present and provides forecasts of the highest potential level of respiratory irritation over the next three to four days. Bulletins provide decision-makers with a more in-depth analysis of the location of a current bloom and reported impacts, as well as forecasts of potential development, intensification, transport, and associated impacts of blooms. Both products are updated twice weekly during a bloom.

In addition, NOAA and a network of trained and authorized professionals from state and local organizations work together to respond to stranded marine animals found along the coastline during these events.

Can this red tide event be stopped?

There are currently no means of controlling the occurrence of red tide.

Is this red tide dangerous?

The Florida red tide organism, Karenia brevis, produces potent neurotoxins, called brevetoxins, that can affect the central nervous system of many animals, causing them to die. That is why red tides are often associated with fish kills. Mortalities of other species, including manatees, dolphins, sea turtles, and birds also occur.

Wave action near beaches can break open K. brevis cells and release the toxins into the air, leading to respiratory irritation. For people with severe or chronic respiratory conditions, such as emphysema or asthma, red tide can cause serious illness. People with respiratory problems should avoid affected beaches during red tides.

Red tide toxins can also accumulate in filter-feeders mollusks such as oysters and clams, which can lead to Neurotoxic Shellfish Poisoning (NSP) in people who consume contaminated shellfish. While not fatal, NSP causes diarrhea and discomfort for about three days. Rigorous state monitoring of cells and toxins is conducted to close commercial shellfish harvesting if necessary to protect human health. Recreational shellfish harvesters should check State web pages to make sure it is safe to consume shellfish.

Is it still safe to go to the beach?

Some areas may be more affected than others. Check NOAA forecasts to assist in locating unaffected areas, and learn more about red tide health concerns from Florida Health.

Is this normal?

This year’s bloom is different from what we’ve seen before in several ways:

Timing: Blooms of this alga typically start in late summer or early fall. The last large early summer bloom was in 2005. The current bloom started last fall and is still going.

Duration: While not unprecedented in its duration, this bloom is unusually persistent. It started in October 2017 and continued through spring of 2018. By early summer, the bloom resurged and was detected in five southwest Florida counties. Some shellfish harvesting areas have been closed since November 2017.

Size: The size of the bloom changes from week to week, and it is patchy. Not every beach is affected every day, so it is important to stay up to date with the NOAA conditions report. As of August 15, the bloom stretched from Pinellas County to Collier County, more than 150 miles.

While the timing, duration, and size of this red tide are unusual, red tides are not new to the Gulf Coast. Red tides were documented in the southern Gulf of Mexico as far back as the 1700s and along Florida’s Gulf coast in the 1840s. Fish kills near Tampa Bay were even mentioned in the records of Spanish explorers. For more information on historical red tide events in Florida, see the Florida Fish and Wildlife Conservation Commission’s harmful algal bloom monitoring database.

What do you do if you see sick, injured, stranded, or dead wildlife?

If you see sick, injured, or stranded wildlife, such as a sea turtle, manatee, dolphin, seabird, or a large fish kill in Florida, report it to the following standing network hotlines. To report an injured, hooked, entangled, or stranded sea turtle, call 1-877-942-5343. To report other sick or injured wildlife and fish kills, contact FWC Wildlife Alert or call 888-404-FWCC (888-404-3922). If you see dead or injured marine mammals, call 1-877-WHALE HELP (1-877-942-5343). You can also report via the Dolphin and Whale 911 Phone App.

What is the projected effect of this red tide on marine life? How long will it take for impacted marine life to recover?

There is no way to project the cumulative effects of this red tide event. Red tide occurs naturally in coastal waters of the Gulf of Mexico with blooms appearing seasonally. Although the Florida red tide organism, Karenia brevis, typically blooms between August and December, blooms often deviate from that time frame. The current bloom continues to be monitored by our local and state partners. Visit the Florida Fish and Wildlife Conservation Commission’s (FWC) red tide status page. Reports of fish kills and marine animal deaths are made publicly available on FWC’s website. For more information on the effects of red tide on marine animals, shellfish, and people, visit our health information page for more information.

Can NOAA provide travel advice for people planning to visit this region?

While NOAA provides regional harmful algal bloom forecasts and supports research to better understand the causes, impacts, and effects of these events, we are not in a position to provide travel advice. We have provided links to Florida state resources in the right column of this announcement that we hope will help people make informed decisions about their travel plans.

Resources for More Information:

NOAA Resources

- Gulf of Mexico Harmful Algal Bloom Forecast: NOAA’s Red Tide Bulletins are issued twice weekly during a red tide event.

- General information and resources about harmful algal blooms: NOAA portal with links to educational information about harmful algal blooms.

- Harmful Algal Bloom Detection and Resources: NOAA National Centers for Coastal Ocean Science projects, news, products, data, and general information related to harmful algal blooms.

- What is a red tide?: View our infographics to learn about red tide and NOAA harmful algal bloom forecasting.

Florida Resources

- Algal Bloom Monitoring and Support: Consolidated site from Florida Department of Environmental Protection portal for all Florida algal bloom resources.

- Red Tide Blooms: Florida Department of Health Red Tide Information

- Fish and Wildlife Research Institute Red Tide Resources: Red tide status, frequently asked questions, tools for tracking red tides, and general information from Florida Fish and Wildlife Conservation Commission

- Aquatic Toxins: Poison Control Center: Resources on aquatic toxins, to include Florida red tide, from Florida’s Poison Control Center.

- Visitbeaches.org: Mote Marine Lab’s Beach Conditions Report & Red Tide Information

General Information about Red Tide and NOAA’s Role in HAB Forecasting

What is red tide?

Harmful algal blooms occur nearly every summer along the nation’s coasts. Often, the blooms turn the water a deep red. While many people call all such events “red tides,” scientists prefer the term harmful algal bloom or HAB. A red tide or HAB results from the rapid growth of microscopic algae. Some produce toxins that have harmful effects on people, fish, marine mammals, and birds. In Florida and Texas, this is primarily caused by the harmful algae species Karenia brevis. Red tide can result in varying levels of eye and respiratory irritation for people, which may be more severe for those with preexisting respiratory conditions (such as asthma). The blooms can also cause large fish kills and discolored water along the coast.

Red Tide in Florida and Texas

Red Tide in Florida and Texas is caused by the rapid growth of a microscopic algae called Karenia brevis. When large amounts of this algae are present, it can cause a harmful algal bloom (HAB) that can be seen from space. NOAA issues HAB forecasts based on satellite imagery and cell counts of Karenia brevis collected in the field and analyzed by NOAA partners. | Transcript

How Does the NOAA Forecast Work?

NOAA uses a combination of satellite imagery and water samples of the algae species Karenia brevis, collected from the field by local partners, to forecast the location and intensity of red tide events. Satellite imagery is a key tool for detecting blooms before they reach the coast, verifying bloom movement and forecasting potential respiratory irritation.

Why Should You Care?

Red Tide in Florida and Texas produces a toxin that may have harmful effects on marine life. For people, The toxin may also become airborne, which can lead to eye irritation and respiratory issues in people. People with serious respiratory conditions such as asthma may experience more severe symptoms.| Transcript

Putting the Forecast into Action

The condition reports for red tide in Florida and Texas are available to the public and give the daily level of respiratory irritation forecasts by coastal region. NOAA also issues HAB bulletins that contain analyses of ocean color satellite imagery, field observations, models, public health reports, and buoy data. The bulletins also contain forecasts of potential Karenia brevis bloom transport, intensification, and associated respiratory irritation based on the analysis of information from partners and data providers. The bulletins are primarily issued to public health managers, natural resource managers, and scientists interested in HABs. A week after the the bulletin is issued, it is posted to the Bulletin Archive where the public can access it.

Making Choices

State and local resources are available to help beachgoers find nearby beaches and coastal areas that are not affected by red tide, but are still nearby. | Transcript

<!–

NOAA Forecasts Can Save Your Beach Day

By paying attention to NOAA’s HAB forecasts, beachgoers can still have a good time along the Florida and Texas coast. The conditions report for Red Tide in Florida and Texas can

be found online. | Transcript

–>

Infographic Transcript: Red Tide

Red Tide in Florida and Texas is caused by the rapid growth of a microscopic algae called Karenia brevis. When large amounts of this algae are present, it can cause a harmful algal bloom (HAB) that can be seen from space. NOAA issues HAB forecasts based on satellite imagery and cell counts of Karenia brevis collected in the field and analyzed by NOAA partners.

Why should you care? Red Tide in Florida and Texas produces a toxin that can have harmful effects for marine life. For people, the toxin can become airborne and cause respiratory issues and eye irritation. These symptoms can be more severe for people with serious respiratory issues such as asthma.

Making Choices. State and local resources are available to help beachgoers find beaches and coastal areas that are not impacted by Red Tide, but are still nearby.

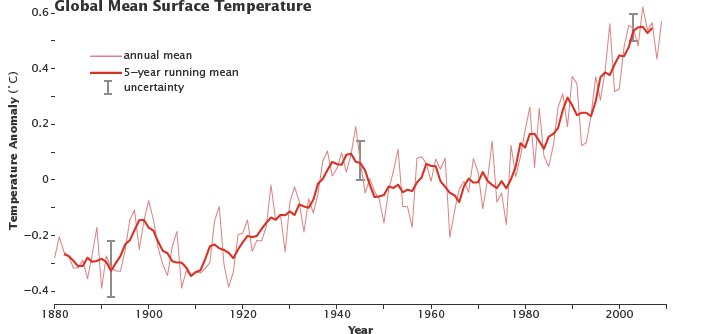

2017 Was the Second Hottest Year on Record

Friday, August 3rd, 2018Earth’s global surface temperatures in 2017 ranked as the second warmest since 1880, according to an analysis by scientists at NASA’s Goddard Institute for Space Studies (GISS). Continuing the planet’s long-term warming trend, globally averaged temperatures in 2017 were 0.90 degrees Celsius (1.62 degrees Fahrenheit) warmer than the 1951 to 1980 mean. That is second only to global temperatures in 2016.

In a separate, independent analysis, scientists at the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) concluded that 2017 was the third-warmest year in their record. The minor difference in rankings is due to slightly different methods used by the two agencies to analyze global temperatures. The long-term records of the two agencies remain in strong agreement, and both analyses show that the five warmest years on record have all taken place since 2010.

The map above depicts global temperature anomalies in 2017, according to the NASA GISS team. The map does not show absolute temperatures; instead, it shows how much warmer or cooler each region of Earth was compared to a baseline average from 1951 to 1980.

Because the locations and measurement practices of weather stations change over time, there are uncertainties in the interpretation of specific year-to-year global mean temperature differences. Taking this into account, NASA estimates that the 2017 global mean change is accurate to within 0.1 degree Fahrenheit, with a 95 percent certainty level.

Large parts of southern and western Europe: Thermometers could reach up to 48C or 118F.

Friday, August 3rd, 2018Global warming & extreme weather disasters

Wednesday, August 1st, 2018Climate as Culprit : Document (NATURE | VOL 560 | 2 AUGUST 2018)

“……scientists had completed “attribution” studies on 190 extreme weather events between 2004 and the middle of 2018. In about two thirds of those cases, the researchers concluded the events had been made more likely, or more severe, because of humanity’s role in warming the Earth.

Last year, for the first time, studies suggested that three weather anomalies — a string of Asian heatwaves, record temperatures around much of the world and ocean warming in the Gulf of Alaska and Bering Sea — wouldn’t have happened were it not for climate change…….”