Archive for the ‘Lassa Fever’ Category

Nigeria: A Lassa fever outbreak affecting people in 16 states has grown to 213 confirmed cases, including 41 deaths.

Tuesday, February 5th, 2019Lassa Fever Outbreak in Benin

Wednesday, December 19th, 2018EVENT DESCRIPTION On 7 December 2018, the Ministry of Health in Benin notified WHO of an outbreak of Lassa fever in Borgou Department, located in the north-east, at the border with Nigeria. The event was initially reported by the departmental health authority on 6 December 2018, following detection of a suspected Lassa fever case in the Departmental University Hospital Centre (CHUD) of Borgou-Alibori in Parakou city.

The case-patient, a 22-year old Beninese housewife who live in Taberou village, Kwara State, Nigeria, reportedly developed a febrile illness on 23 November 2018 while in Nigeria, from where she initially sought medical treatment. However due to lack of improvement, the family brought her back home to Benin on 29 November 2018 and she was admitted to the teaching hospital (the same day), presenting with fever, haematemesis (vomiting blood), and melaena (blood in her stools). The disease eventually progressed in the subsequent days, with conjunctival hyperaemia, severe weakness and dysphagia, among other symptoms. Blood and urine specimens were obtained and shipped to the viral haemorrhagic fever national laboratory in Cotonou, arriving on 6 December 2018. Test results released on 7 December 2018 were positive for Lassa fever by reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR).

On 6 December 2018, the spouse of the confirmed index case was found to have symptoms and a blood specimen was obtained, and the test result also turned out positive for Lassa fever. On 9 December 2018, one of the two children of the confirmed cases (a couple) developed high fever and a blood specimen was obtained and the initial test result was negative. However, a repeat sample tested positive for Lassa fever.

As of 16 December 2018, three confirmed cases have been reported, with no deaths. The three patients are admitted in the CHUD and all are reported to be in good clinical condition. A total of 33 contacts, including 24 health professionals, four carers and four patients, have been identified and are being monitored. Further epidemiological investigations are ongoing.

PUBLIC HEALTH ACTIONS On 7 December 2018, the Minister of Health held a press conference to declare the Lassa fever outbreak and provide information on preventive measures to the public. The Ministry of Health convened an emergency meeting of the Crisis Management Committee (CMC) on 7 December 2018 to plan and institute response measures to the outbreak. Structures of the CMC have been activated, including the sub-committees and coordination meetings have been scheduled at the national and sub-national levels. The national rapid response team have been deployed to the affected area to conduct detailed epidemiological investigations and support local response efforts. Isolation and treatment rooms have been prepared to manage the suspected and confirmed cases. Medical commodities, including personal protective equipment, medicines, and medical consumables previously positioned are being used, while additional supplies are being mobilized. Surveillance has been enhanced, including active case search, identification and follow-up of contacts. Public health education and sensitization of the population is ongoing, in particular native healers, opinion, religious and traditional leaders. Dissemination of public awareness messages on prevention measures through local radios and other communication channels is taking place. Aware raising activities have been conducted, targeting taxi and motorcycle-taxi drivers, community relays, religious leaders, teachers and traditional healers, aimed to improve case detection and prevention of Lassa fever infections.

SITUATION INTERPRETATION An outbreak of Lassa fever has been confirmed in Benin, with an epidemiological link to Kwara State in Nigeria. The national authorities have moved quickly in the bid to contain this outbreak, to prevent further spread and establishment of local transmission. Several measures have been instituted, including contact identification and follow-up, aimed to promptly detect, isolate and investigate suspected cases for speedy laboratory confirmation. Further investigations are also ongoing to better understand the outbreak.

However, this event should be a wakeup call to the national authorities to step up preparedness measures for Lassa fever across the country, especially along the borders with Nigeria. Functional port health services and cross border surveillance is paramount, in light of the fact that the index case in this event crossed the border with symptoms. Improving routine universal precautions in healthcare settings is also critical, since about 70% of contacts during this event are health professionals.

Geographical

Weekly Epidemiological Report from the Nigeria CDC

Monday, October 22nd, 2018In the reporting week ending on September 30, 2018:

o There were 173 new cases of Acute Flaccid Paralysis (AFP) reported. None was confirmed as polio. The last reported case of polio in Nigeria was in August 2016. Active case search for AFP is being intensified with the goal to eliminate polio in Nigeria.

o There were 2052 suspected cases of Cholera reported from 42 LGAs in seven States (Adamawa – 107, Borno – 702, Gombe – 90, Kaduna – 2, Katsina – 585, Yobe – 162 and Zamfara – 404). Of these, 26 were laboratory confirmed and 18 deaths were recorded.

o Nine suspected cases of Lassa fever were reported from seven LGAs in five States (Bauchi – 1, Edo – 5, FCT – 1, Nasarawa – 1 & Rivers – 1). Four were laboratory confirmed and no death was recorded.

o There were eight suspected cases of Cerebrospinal Meningitis (CSM) reported from five LGAs in five States (Ebonyi – 1, Edo – 2, Ondo – 2, Taraba – 1 & Yobe – 2). Of these, none was laboratory confirmed and no death was recorded.

o There were 124 suspected cases of measles reported from 30 States. None was laboratory confirmed and one death was recorded.

Lassa Fever: 9 new confirmed cases were reported from three different states in Nigeria

Friday, August 17th, 2018In the reporting Week 31 (July 30-August 5, 2018) nine new confirmedi cases were reported from Edo(7), Ondo(1) and Enugu(1) with two new deaths from Edo(1) and Enugu (1)

Enugu state recorded the first confirmed case in the state since the beginning of the outbreak with death in the confirmed case From 1st January to 5th August 2018, a total of 2334 suspected cases have been reported from 22 states. Of these, 481 were confirmed positive, 10 are probable, 1844 negative (not a case)

Since the onset of the 2018 outbreak, there have been 123 deaths in confirmed cases and 10 in probable cases.

Case Fatality Rate in confirmed cases is 25.6%

In the reporting week 31, no new healthcare worker was infected. Thirty-nine health care workers have been affected since the onset of the outbreak in seven states

A total of 6383 contacts have been identified from 22 states. Of these 439(6.9%) are currently being followed up, 5846 (91.6%) have completed 21 days follow up while 10(0.2%) were lost to follow up. 88 (1.4%) symptomatic contacts have been identified, of which 30 (34%) have tested positive from five states

Lassa fever national multi-partner, multi-agency Technical Working Group(TWG) continues to coordinate response activities at all levels

WHO: List of Blueprint priority diseases (i.e. diseases and pathogens to prioritize for research and development in public health emergency contexts)

Tuesday, May 22nd, 20182018 annual review of the Blueprint list of priority diseases

For the purposes of the R&D Blueprint, WHO has developed a special tool for determining which diseases and pathogens to prioritize for research and development in public health emergency contexts. This tool seeks to identify those diseases that pose a public health risk because of their epidemic potential and for which there are no, or insufficient, countermeasures. The diseases identified through this process are the focus of the work of R& D Blueprint. This is not an exhaustive list, nor does it indicate the most likely causes of the next epidemic.

The first list of prioritized diseases was released in December 2015.

Using a published prioritization methodology, the list was first reviewed in January 2017.

February 2018 – Second annual review

The second annual review occurred 6-7 February, 2018. Experts consider that given their potential to cause a public health emergency and the absence of efficacious drugs and/or vaccines, there is an urgent need for accelerated research and development for*:

- Crimean-Congo haemorrhagic fever (CCHF)

- Ebola virus disease and Marburg virus disease

- Lassa fever

- Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus (MERS-CoV) and Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome (SARS)

- Nipah and henipaviral diseases

- Rift Valley fever (RVF)

- Zika

- Disease X

Disease X represents the knowledge that a serious international epidemic could be caused by a pathogen currently unknown to cause human disease, and so the R&D Blueprint explicitly seeks to enable cross-cutting R&D preparedness that is also relevant for an unknown “Disease X” as far as possible.

A number of additional diseases were discussed and considered for inclusion in the priority list, including: Arenaviral hemorrhagic fevers other than Lassa Fever; Chikungunya; highly pathogenic coronaviral diseases other than MERS and SARS; emergent non-polio enteroviruses (including EV71, D68); and Severe Fever with Thrombocytopenia Syndrome (SFTS).

These diseases pose major public health risks and further research and development is needed, including surveillance and diagnostics. They should be watched carefully and considered again at the next annual review. Efforts in the interim to understand and mitigate them are encouraged.

Although not included on the list of diseases to be considered at the meeting, monkeypox and leptospirosis were discussed and experts stressed the risks they pose to public health. There was agreement on the need for: rapid evaluation of available potential countermeasures; the establishment of more comprehensive surveillance and diagnostics; and accelerated research and development and public health action.

Several diseases were determined to be outside of the current scope of the Blueprint: dengue, yellow fever, HIV/AIDs, tuberculosis, malaria, influenza causing severe human disease, smallpox, cholera, leishmaniasis, West Nile Virus and plague. These diseases continue to pose major public health problems and further research and development is needed through existing major disease control initiatives, extensive R&D pipelines, existing funding streams, or established regulatory pathways for improved interventions. In particular, experts recognized the need for improved diagnostics and vaccines for pneumonic plague and additional support for more effective therapeutics against leishmaniasis.

The experts also noted that:

- For many of the diseases discussed, as well as many other diseases with the potential to cause a public health emergency, there is a need for better diagnostics.

- Existing drugs and vaccines need further improvement for several of the diseases considered but not included in the priority list.

- Any type of pathogen could be prioritised under the Blueprint, not only viruses.

- Necessary research includes basic/fundamental and characterization research as well as epidemiological, entomological or multidisciplinary studies, or further elucidation of transmission routes, as well as social science research.

- There is a need to assess the value, where possible, of developing countermeasures for multiple diseases or for families of pathogens.

The impact of environmental issues on diseases with the potential to cause public health emergencies was discussed. This may need to be considered as part of future reviews.

The importance of the diseases discussed was considered for special populations, such as refugees, internally displaced populations, and victims of disasters.

The value of a One Health approach was stressed, including a parallel prioritization processes for animal health. Such an effort would support research and development to prevent and control animal diseases minimising spill-over and enhancing food security. The possible utility of animal vaccines for preventing public health emergencies was also noted.

Also there are concerted efforts to address anti-microbial resistance through specific international initiatives. The possibility was not excluded that, in the future, a resistant pathogen might emerge and appropriately be prioritized.

*The order of diseases on this list does not denote any ranking of priority.

WHO: Nigeria’s Lassa fever outbreak is contained

Saturday, May 12th, 2018Abuja, 10 May 2018 – With six weeks of declining numbers and only a handful of confirmed cases reported in recent weeks, the critical phase of Nigeria’s largest-ever Lassa fever outbreak is under control, according to the World Health Organization (WHO). However, Nigeria is endemic for Lassa fever and people could be infected throughout the year, making continued efforts to control any new flare ups crucial.

In the last reporting week, ending on 6 May 2018, three new confirmed cases of Lassa fever were reported. This year a total of 423 confirmed cases including 106 deaths have been recorded. The national case numbers have consistently declined in the past six weeks, and have dropped below levels considered to be a national emergency when compared with data from previous outbreaks.

“Nigeria is to be congratulated for reaching this important milestone in the fight against Lassa fever,” says Dr Ibrahima Socé Fall, Regional Emergencies Director for Africa. “But we cannot let our foot off the pedal. We must use the lessons learnt to better prepare at risk countries in our region to conduct rapid detection and response.”

WHO will continue to support the Nigerian government to maintain an intensified response to the current Lassa fever outbreak in Nigeria. Thirty-seven health workers have been infected with Lassa fever, eight have died. This highlights the need for implementing standard infection prevention and control precautions with all patients – regardless of their diagnosis – in all work practices at all times. WHO continues to help states which have reported new cases by strengthening their capacity to conduct disease surveillance, treat patients, as well as implement infection prevention and control measures, laboratory diagnostics, and engage with communities.

WHO Country Representative Dr Wondimagegnehu Alemu said, “Communities are encouraged to remain vigilant and report any rumors to the nearest health facilities because early diagnosis and treatment can save lives.”

Health care workers are urged to maintain a high index of suspicion for Lassa fever when handling patients, irrespective of their health status. Lassa fever should always be considered in patients with fever, headache, sore throat and general body weakness, especially when malaria has been ruled out with a rapid diagnostic test (RDT), and when patients are not improving. Health workers should adhere to standard precautions, and wear protective equipment like gloves, face masks, face shields and aprons when handling suspected Lassa fever patients.

WHO is monitoring and supporting Nigeria’s neighbouring countries to help improve their level of preparedness to readily respond to any potential outbreaks.

Note to the editors:

Lassa fever is a viral infection, primarily transmitted to humans through contact with food or household items contaminated with rodent urine, faeces, or blood. Person-to-person transmission is through direct or indirect contact with body fluids of an infected person. Prevention of Lassa fever relies on promoting good community hygiene to keep rats out of the house and prevent contamination of food supplies. Effective measures include storing grains and other foodstuff in rodent-proof containers, proper disposal of garbage far from the home, and maintaining clean households.

Nigeria: In the reporting Week 17 (April 23-29, 2018) four new confirmed Lassa Fever cases with one new death.

Thursday, May 3rd, 2018- From Jan 1 to Apr 29, the NCDC has confirmed 420 Lassa fever cases, along with 106 deaths.

- The case-fatality rate is at 25.2 %.

- None of the new cases involved health workers.

- 37 healthcare workers have been sickened in the outbreak.

Lassa in Nigeria: There are now 408 confirmed and 9 probable cases in Nigeria’s largest-ever Lassa outbreak.

Wednesday, April 11th, 2018- In the reporting Week 14 (April 02-08, 2018) eight new confirmed cases were recorded from five States –

- From 1st January to 8th April 2018, a total of 1781 suspected cases have been reported from 20 states. Of these, 408 were confirmed positive, 9 are probable, 1351 are negative (not a case) and 13 are awaiting laboratory results (pending)

- Since the onset of the 2018 outbreak, there have been 101 deaths in confirmed cases, 9 in probable cases. Case Fatality Ratio in confirmed cases is 24.8%

Lassa Fever: A WHO Review

Saturday, April 7th, 2018Key Facts

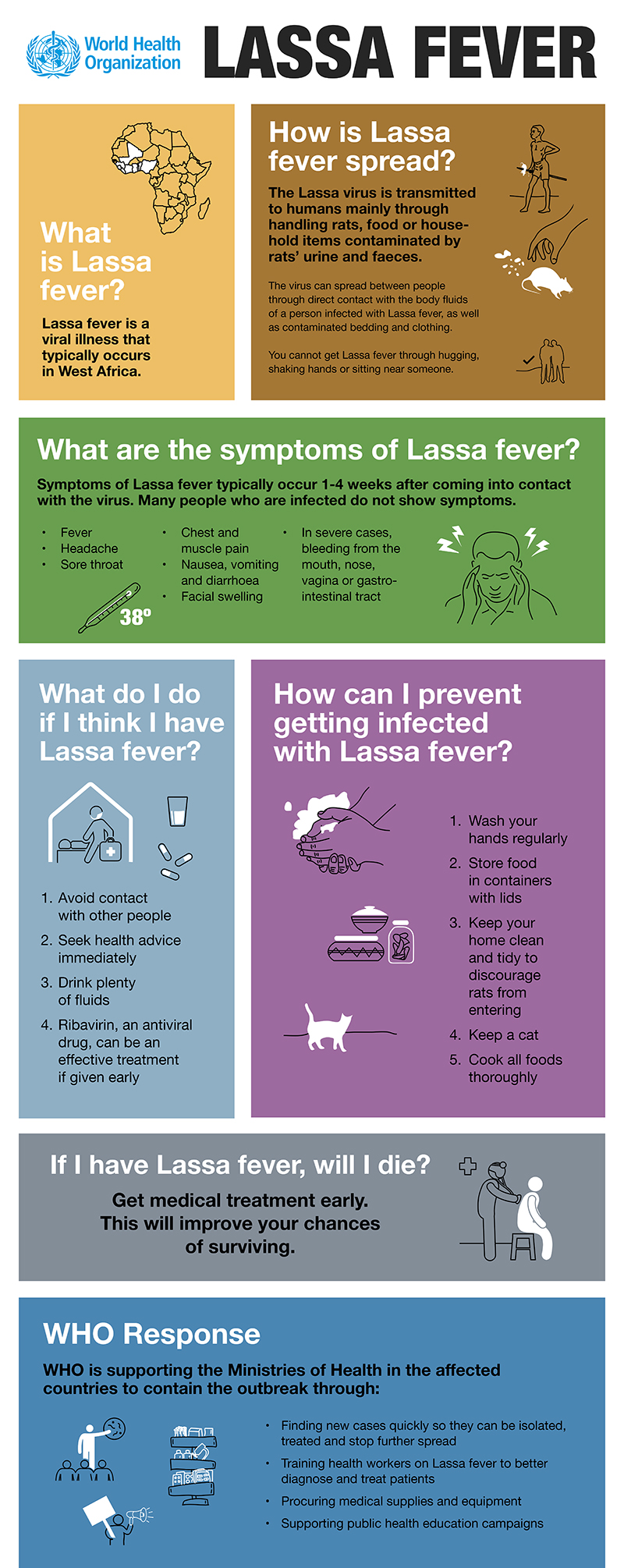

- Lassa fever is an acute viral haemorrhagic illness of 2-21 days duration that occurs in West Africa.

- The Lassa virus is transmitted to humans via contact with food or household items contaminated with rodent urine or faeces.

- Person-to-person infections and laboratory transmission can also occur, particularly in hospitals lacking adequate infection prevention and control measures.

- Lassa fever is known to be endemic in Benin, Ghana, Guinea, Liberia, Mali, Sierra Leone, and Nigeria, but probably exists in other West African countries as well.

- The overall case-fatality rate is 1%. Observed case-fatality rate among patients hospitalized with severe cases of Lassa fever is 15%.

- Early supportive care with rehydration and symptomatic treatment improves survival.

Though first described in the 1950s, the virus causing Lassa disease was not identified until 1969. The virus is a single-stranded RNA virus belonging to the virus family Arenaviridae.

About 80% of people who become infected with Lassa virus have no symptoms. 1 in 5 infections result in severe disease, where the virus affects several organs such as the liver, spleen and kidneys.

Lassa fever is a zoonotic disease, meaning that humans become infected from contact with infected animals. The animal reservoir, or host, of Lassa virus is a rodent of the genus Mastomys, commonly known as the “multimammate rat.” Mastomys rats infected with Lassa virus do not become ill, but they can shed the virus in their urine and faeces.

Because the clinical course of the disease is so variable, detection of the disease in affected patients has been difficult. When presence of the disease is confirmed in a community, however, prompt isolation of affected patients, good infection prevention and control practices, and rigorous contact tracing can stop outbreaks.

Lassa fever is known to be endemic in Benin (where it was diagnosed for the first time in November 2014), Ghana (diagnosed for the first time in October 2011), Guinea, Liberia, Mali (diagnosed for the first time in February 2009), Sierra Leone, and Nigeria, but probably exists in other West African countries as well.

The incubation period of Lassa fever ranges from 6–21 days. The onset of the disease, when it is symptomatic, is usually gradual, starting with fever, general weakness, and malaise. After a few days, headache, sore throat, muscle pain, chest pain, nausea, vomiting, diarrhoea, cough, and abdominal pain may follow. In severe cases facial swelling, fluid in the lung cavity, bleeding from the mouth, nose, vagina or gastrointestinal tract and low blood pressure may develop.

Protein may be noted in the urine. Shock, seizures, tremor, disorientation, and coma may be seen in the later stages. Deafness occurs in 25% of patients who survive the disease. In half of these cases, hearing returns partially after 1–3 months. Transient hair loss and gait disturbance may occur during recovery.

Death usually occurs within 14 days of onset in fatal cases. The disease is especially severe late in pregnancy, with maternal death and/or fetal loss occurring in more than 80% of cases during the third trimester.

Humans usually become infected with Lassa virus from exposure to urine or faeces of infected Mastomys rats. Lassa virus may also be spread between humans through direct contact with the blood, urine, faeces, or other bodily secretions of a person infected with Lassa fever. There is no epidemiological evidence supporting airborne spread between humans. Person-to-person transmission occurs in both community and health-care settings, where the virus may be spread by contaminated medical equipment, such as re-used needles. Sexual transmission of Lassa virus has been reported.

Lassa fever occurs in all age groups and both sexes. Persons at greatest risk are those living in rural areas where Mastomys are usually found, especially in communities with poor sanitation or crowded living conditions. Health workers are at risk if caring for Lassa fever patients in the absence of proper barrier nursing and infection prevention and control practices.

Because the symptoms of Lassa fever are so varied and non-specific, clinical diagnosis is often difficult, especially early in the course of the disease. Lassa fever is difficult to distinguish from other viral haemorrhagic fevers such as Ebola virus disease as well as other diseases that cause fever, including malaria, shigellosis, typhoid fever and yellow fever.

Definitive diagnosis requires testing that is available only in reference laboratories. Laboratory specimens may be hazardous and must be handled with extreme care. Lassa virus infections can only be diagnosed definitively in the laboratory using the following tests:

- reverse transcriptase polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) assay

- antibody enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA)

- antigen detection tests

- virus isolation by cell culture.

The antiviral drug ribavirin seems to be an effective treatment for Lassa fever if given early on in the course of clinical illness. There is no evidence to support the role of ribavirin as post-exposure prophylactic treatment for Lassa fever.

There is currently no vaccine that protects against Lassa fever.

Prevention of Lassa fever relies on promoting good “community hygiene” to discourage rodents from entering homes. Effective measures include storing grain and other foodstuffs in rodent-proof containers, disposing of garbage far from the home, maintaining clean households and keeping cats. Because Mastomys are so abundant in endemic areas, it is not possible to completely eliminate them from the environment. Family members should always be careful to avoid contact with blood and body fluids while caring for sick persons.

In health-care settings, staff should always apply standard infection prevention and control precautions when caring for patients, regardless of their presumed diagnosis. These include basic hand hygiene, respiratory hygiene, use of personal protective equipment (to block splashes or other contact with infected materials), safe injection practices and safe burial practices.

Health-care workers caring for patients with suspected or confirmed Lassa fever should apply extra infection control measures to prevent contact with the patient’s blood and body fluids and contaminated surfaces or materials such as clothing and bedding. When in close contact (within 1 metre) of patients with Lassa fever, health-care workers should wear face protection (a face shield or a medical mask and goggles), a clean, non-sterile long-sleeved gown, and gloves (sterile gloves for some procedures).

Laboratory workers are also at risk. Samples taken from humans and animals for investigation of Lassa virus infection should be handled by trained staff and processed in suitably equipped laboratories under maximum biological containment conditions.

On rare occasions, travellers from areas where Lassa fever is endemic export the disease to other countries. Although malaria, typhoid fever, and many other tropical infections are much more common, the diagnosis of Lassa fever should be considered in febrile patients returning from West Africa, especially if they have had exposures in rural areas or hospitals in countries where Lassa fever is known to be endemic. Health-care workers seeing a patient suspected to have Lassa fever should immediately contact local and national experts for advice and to arrange for laboratory testing.

The Nigerian Centre for Disease Control reported 6 new confirmed cases of Lassa fever last week, including two deaths. One of those deaths involved a doctor who was in close contact with at least 30 patients.

Thursday, April 5th, 2018In the reporting Week 13 (March 26- April 01, 2018) six new confirmed cases were recorded from five States…..with two new deaths in confirmed cases from FCT (1) and Abia (1)

From 1st January to 1st April 2018, a total of 1706 suspectedi cases have been reported. Of these, 400 were confirmed positive, 9 are probable, 1273 are negative (not a case) and 24 are awaiting laboratory results (pending) Since the onset of the 2018 outbreak, there have been 142 deaths: 97 in positive-confirmed cases, 9 in probable cases and 36 in negative cases.

Case Fatality Rate in confirmed cases is 24.3% –

In the reporting week 14, two new healthcare workers were affected with one death. Twenty five* health care workers have been affected since the onset of the outbreak in eight states –

30 cases are currently under treatment in treatment centres across nine states -Edo (9), Ebonyi (6), Bauchi (7), Ondo (5), Plateau (1), Osun (1) and Kogi (1)

A total of 4274 contacts have been identified from 20 states. Of these 662 (15.0%) are currently being followed up, 3605 (84.8%) have completed 21 days follow up while 7(0.2%) were lost follow up. 27 (40%) of the 67 contacts have tested positive from five states (Edo-12, Ondo-7, Ebonyi-3, Kogi -3 and Bauchi-1) WHO and NCDC has scaled up response at National and State levels National RRT team (NCDC staff and NFELTP residents) batch C continues response support in Ebonyi, Ondo, Edo, Bauchi and Taraba State

National Lassa fever multi-partner multi-agency Emergency Operations Centre (EOC) continues to coordinate the response activities at all levels