Archive for the ‘Yellow Fever’ Category

EPA Registers the Wolbachia ZAP Strain in Live Male Asian Tiger Mosquitoes in order to reduce their population thereby reducing the spread numerous diseases of significant human health concern

Thursday, November 9th, 2017

For Release: November 7, 2017

On November 3, 2017, EPA registered a new mosquito biopesticide – ZAP Males® – that can reduce local populations of the type of mosquito (Aedes albopictus, or Asian Tiger Mosquitoes) that can spread numerous diseases of significant human health concern, including the Zika virus.

ZAP Males® are live male mosquitoes that are infected with the ZAP strain, a particular strain of the Wolbachia bacterium. Infected males mate with females, which then produce offspring that do not survive. (Male mosquitoes do not bite people.) With continued releases of the ZAP Males®, local Aedes albopictus populations decrease. Wolbachia are naturally occurring bacteria commonly found in most insect species.

This time-limited registration allows MosquitoMate, Inc. to sell the Wolbachia-infected male mosquitoes for five years in the District of Columbia and the following states: California, Connecticut, Delaware, Illinois, Indiana, Kentucky, Massachusetts, Maine, Maryland, Missouri, New Hampshire, New Jersey, Nevada, New York, Ohio, Pennsylvania, Rhode Island, Tennessee, Vermont, and West Virginia. Before the ZAP Males® can be used in each of those jurisdictions, it must be registered in the state or district.

When the five-year time limit ends, the registration will expire unless the registrant requests further action from EPA.

EPA’s risk assessments, along with the pesticide labeling, EPA’s response to public comments on the Notice of Receipt, and the proposed registration decision, can be found on www.regulations.gov under docket number EPA-HQ-OPP-2016-0205.

CDC recommendations to healthcare providers treating patients in Puerto Rico and USVI, as well as those treating patients in the continental US who recently traveled in hurricane-affected areas during the period of September 2017 – March 2018.

Wednesday, October 25th, 2017Advice for Providers Treating Patients in or Recently Returned from Hurricane-Affected Areas, Including Puerto Rico and US Virgin Islands

Distributed via the CDC Health Alert Network

October 24, 2017, 1330 ET (1:30 PM ET)

CDCHAN-00408

Summary

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) is working with federal, state, territorial, and local agencies and global health partners in response to recent hurricanes. CDC is aware of media reports and anecdotal accounts of various infectious diseases in hurricane-affected areas, including Puerto Rico and the US Virgin Islands (USVI). Because of compromised drinking water and decreased access to safe water, food, and shelter, the conditions for outbreaks of infectious diseases exist.

The purpose of this HAN advisory is to remind clinicians assessing patients currently in or recently returned from hurricane-affected areas to be vigilant in looking for certain infectious diseases, including leptospirosis, dengue, hepatitis A, typhoid fever, vibriosis, and influenza. Additionally, this Advisory provides guidance to state and territorial health departments on enhanced disease reporting.

Background

Hurricanes Irma and Maria made landfall in Puerto Rico and USVI in September 2017, causing widespread flooding and devastation. Natural hazards associated with the storms continue to affect many areas. Infectious disease outbreaks of diarrheal and respiratory illnesses can occur when access to safe water and sewage systems are disrupted and personal hygiene is difficult to maintain. Additionally, vector borne diseases can occur due to increased mosquito breeding in standing water; both Puerto Rico and USVI are at risk for outbreaks of dengue, Zika, and chikungunya.

Health care providers and public health practitioners should be aware that post-hurricane environmental conditions may pose an increased risk for the spread of infectious diseases among patients in or recently returned from hurricane-affected areas; including leptospirosis, dengue, hepatitis A, typhoid fever, vibriosis, and influenza. The period of heightened risk may last through March 2018, based on current predictions of full restoration of power and safe water systems in Puerto Rico and USVI.

In addition, providers in health care facilities that have experienced water damage or contaminated water systems should be aware of the potential for increased risk of infections in those facilities due to invasive fungi, nontuberculous Mycobacterium species, Legionella species, and other Gram-negative bacteria associated with water (e.g., Pseudomonas), especially among critically ill or immunocompromised patients.

Cholera has not occurred in Puerto Rico or USVI in many decades and is not expected to occur post-hurricane.

Recommendations

These recommendations apply to healthcare providers treating patients in Puerto Rico and USVI, as well as those treating patients in the continental US who recently traveled in hurricane-affected areas (e.g., within the past 4 weeks), during the period of September 2017 – March 2018.

- Health care providers and public health practitioners in hurricane-affected areas should look for community and healthcare-associated infectious diseases.

- Health care providers in the continental US are encouraged to ask patients about recent travel (e.g., within the past 4 weeks) to hurricane-affected areas.

- All healthcare providers should consider less common infectious disease etiologies in patients presenting with evidence of acute respiratory illness, gastroenteritis, renal or hepatic failure, wound infection, or other febrile illness. Some particularly important infectious diseases to consider include leptospirosis, dengue, hepatitis A, typhoid fever, vibriosis, and influenza.

- In the context of limited laboratory resources in hurricane-affected areas, health care providers should contact their territorial or state health department if they need assistance with ordering specific diagnostic tests.

- For certain conditions, such as leptospirosis, empiric therapy should be considered pending results of diagnostic tests— treatment for leptospirosis is most effective when initiated early in the disease process. Providers can contact their territorial or state health department or CDC for consultation.

- Local health care providers are strongly encouraged to report patients for whom there is a high level of suspicion for leptospirosis, dengue, hepatitis A, typhoid, and vibriosis to their local health authorities, while awaiting laboratory confirmation.

- Confirmed cases of leptospirosis, dengue, hepatitis A, typhoid fever, and vibriosis should be immediately reported to the territorial or state health department to facilitate public health investigation and, as appropriate, mitigate the risk of local transmission. While some of these conditions are not listed as reportable conditions in all states, they are conditions of public health importance and should be reported.

For More Information

- General health information about hurricanes and other tropical storms: https://www.cdc.gov/disasters/hurricanes/index.html

- Information about Hurricane Maria: https://www.cdc.gov/disasters/hurricanes/hurricane_maria.html

- Information for Travelers:

- Travel notice for Hurricanes Irma and Maria in the Caribbean: https://wwwnc.cdc.gov/travel/notices/alert/hurricane-irma-in-the-caribbean

- Health advice for travelers to Puerto Rico: https://wwwnc.cdc.gov/travel/destinations/traveler/none/puerto-rico?s_cid=ncezid-dgmq-travel-single-001

- Health advice for travelers to the U.S. Virgin Islands: https://wwwnc.cdc.gov/travel/destinations/traveler/none/usvirgin-islands?s_cid=ncezid-dgmq-travel-leftnav-traveler

- Resources from CDC Health Information for International Travel 2018 (the Yellow Book):

- Post-travel Evaluation: https://wwwnc.cdc.gov/travel/yellowbook/2018/post-travel-evaluation/general-approach-to-the-returned-traveler

- Information about infectious diseases after a disaster: https://www.cdc.gov/disasters/disease/infectious.html

- Dengue: https://www.cdc.gov/dengue/index.html

- Hepatitis A: https://www.cdc.gov/hepatitis/HAV/index.htm

- Leptospirosis: https://www.cdc.gov/leptospirosis/

- Typhoid fever: https://www.cdc.gov/typhoid-fever/index.html

- Vibriosis: https://www.cdc.gov/vibrio/index.html

- Information about other infectious diseases of concern:

- Conjunctivitis: https://www.cdc.gov/conjunctivitis/

- Influenza: https://www.cdc.gov/flu/index.htm

- Scabies: https://www.cdc.gov/parasites/scabies/index.html

- Tetanus and wound management: https://www.cdc.gov/disasters/emergwoundhcp.html

- Tetanus in Areas Affected by a Hurricane: Guidelines for Clinicians https://emergency.cdc.gov/coca/cocanow/2017/2017sept12.asp

Disease-carrying mosquitoes may be moving into new ecological niches with greater frequency.

Friday, September 8th, 2017“…..The website, ProMED mail, has carried more than a dozen such reports since June, all involving mosquito species known to transmit human diseases.

Most reports have concerned the United States, where, for example, Aedes aegypti — the yellow fever mosquito, which also spreads Zika, dengue and chikungunya — has been turning up in counties in California and Nevada where it had never, or only rarely, been seen.

Other reports have noted mosquito species found for the first time on certain South Pacific islands, or in parts of Europe where harsh winters previously kept them at bay…..”

An adult Aedes aegypti mosquito, the species responsible for the majority of human Zika virus cases, has been found in Canada for the first time.

Friday, August 25th, 2017WHO: New vector control response seen as game-changer

Friday, June 2nd, 2017The call came from the WHO Director-General in May 2016 for a renewed attack on the global spread of vector-borne diseases.

“What we are seeing now looks more and more like a dramatic resurgence of the threat from emerging and re-emerging infectious diseases,” Dr Margaret Chan told Member States at the Sixty-ninth World Health Assembly. “The world is not prepared to cope.”

Dr Chan noted that the spread of Zika virus disease, the resurgence of dengue, and the emerging threat from chikungunya were the result of weak mosquito control policies from the 1970s. It was during that decade that funding and efforts for vector control were greatly reduced.

‘Vector control has not been a priority’

Dr Ana Carolina Silva Santelli has witnessed this first-hand. As former head of the programme for malaria, dengue, Zika and chikungunya with Brazil’s Ministry of Health, she saw vector-control efforts wane over her 13 years there. Equipment such as spraying machines, supplies such as insecticides and personnel such as entomologists were not replaced as needed. “Vector control has not been a priority,” she said.

Today more than 80% of the world’s population is at risk of vector-borne disease, with half at risk of two or more diseases. Mosquitoes can transmit, among other diseases, malaria, lymphatic filariasis, Japanese encephalitis and West Nile; flies can transmit onchocerciasis, leishmaniasis and human African trypanosomiasis (sleeping sickness); and bugs or ticks can transmit Chagas disease, Lyme disease and encephalitis.

Together, the major vector-borne diseases kill more than 700 000 people each year, with populations in poverty-stricken tropical and subtropical areas at highest risk. Other vector-borne diseases, such as tick-borne encephalitis, are of increasing concern in temperate regions.

Rapid unplanned urbanization, massive increases in international travel and trade, altered agricultural practices and other environmental changes are fuelling the spread of vectors worldwide, putting more and more people at risk. Malnourished people and those with weakened immunity are especially susceptible.

A new approach

Over the past year, WHO has spearheaded a new strategic approach to reprioritize vector control. The Global Malaria Programme and the Department of Control of Neglected Tropical Diseases – along with the Special Programme for Research and Training in Tropical Diseases, have led a broad consultation tapping into the experience of ministries of health and technical experts. The process was steered by a group of eminent scientists and public health experts led by Dr Santelli and Professor Thomas Scott from the Department of Entomology and Nematology at the University of California, Davis and resulted in the Global Vector Control Response (GVCR) 2017–2030.

At its Seventieth session, the World Health Assembly unanimously welcomed the proposed response.

The GVCR outlines key areas of activity that will radically change the control of vector-borne diseases:

- Aligning action across sectors, since vector control is more than just spraying insecticides or delivering nets. That might mean ministries of health working with city planners to eradicate breeding sites used by mosquitoes;

- Engaging and mobilizing communities to protect themselves and build resilience against future disease outbreaks;

- Enhancing surveillance to trigger early responses to increases in disease or vector populations, and to identify when and why interventions are not working as expected; and

- Scaling-up vector-control tools and using them in combination to maximize impact on disease while minimizing impact on the environment.

Specifically, the new integrated approach calls for national programmes to be realigned so that public health workers can focus on the complete spectrum of relevant vectors and thereby control all of the diseases they cause.

Recognizing that efforts must be adapted to local needs and sustained, the success of the response will depend on the ability of countries to strengthen their vector-control programmes with financial resources and staff.

A call to pursue novel interventions aggressively

The GVCR also calls for the aggressive pursuit of promising novel interventions such as devising new insecticides; creating spatial repellents and odour-baited traps; improving house screening; pursuing development of a common bacterium that stops viruses from replicating inside mosquitoes; and modifying the genes of male mosquitoes so that their offspring die early.

Economic development also brings solutions. “If people lived in houses that had solid floors and windows with screens or air conditioning, they wouldn’t need a bednet,” said Professor Scott. “So, by improving people’s standard of living, we would significantly reduce these diseases.”

The call for a more coherent and holistic approach to vector control does not diminish the considerable advances made against individual vector-borne diseases.

Malaria is a prime example. Over the past 15 years, its incidence in sub-Saharan Africa has been cut by 45% – primarily due to the massive use of insecticide-treated bed nets and spraying of residual insecticides inside houses.

But that success has had a down side.

“We’ve been so successful, in some ways, with our control that we reduced the number of public health entomologists – the people who can do this stuff well,” said Professor Steve Lindsay, a public health entomologist at Durham University in Britain. “We’re a disappearing breed.”

The GVCR calls for countries to invest in a vector-control workforce trained in public health entomology and empowered in health care responses.

“We now need more nuanced control – not one-size-fits-all, but to tailor control to local conditions,” Professor Lindsay said. This is needed to tackle new and emerging diseases, but also to push towards elimination of others such as malaria, he said.

Dr Lindsay noted that, under the new strategic approach, individual diseases such as Zika, dengue and chikungunya will no longer be considered as separate threats. “What this represents is not three different diseases, but one mosquito – Aedes aegypti,” said Professor Lindsay.

GVCR dovetails with Sustainable Development Goals

The GVCR will also help countries achieve at least 6 of the 17 Sustainable Development Goals. Of direct relevance are goal 3 on good health and well-being, goal 6 on clean water and sanitation, and goal 11 on sustainable cities and communities.

The GVCR goals are ambitious – to reduce mortality from vector-borne diseases by at least 75% and incidence by at least 60% by 2030 – and to prevent epidemics in all countries.

The annual price tag is US$ 330 million globally, or about 5 cents per person – for workforce, coordination and surveillance costs. This is a modest additional investment in relation to insecticide-treated nets, indoor sprays and community-based activities, which usually exceed US$ 1 per person protected per year.

It also represents less than 10% of what is currently spent each year on strategies to control vectors that spread malaria, dengue and Chagas disease alone. Ultimately, the shift in focus to integrated and locally adapted vector control will save money.

‘A call for action’

Dr Santelli expressed optimism that the GVCR will help ministries of health around the world gain support from their governments for a renewed focus on vector control.

“Most of all, this document is a call for action,” said Dr Santelli, who now serves as deputy director for epidemiology in the Brasilia office of the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

It will not be easy, she predicts. The work to integrate vector-control efforts across different diseases will require more equipment, more people and more money as well as a change in mentality. “The risk of inaction is greater,” said Dr Santelli, “given the growing number of emerging disease threats.” The potential impact of the GVCR is immense: to put in place new strategies that will reduce overall burden and, in some places, even eliminate these diseases once and for all.

U.S.: There is a yellow fever vaccine shortage but there is a plan for providing safe vaccine at a limited number of clinics until the supply is replenished

Sunday, April 30th, 2017Addressing a Yellow Fever Vaccine Shortage — United States, 2016–2017

Early Release / April 28, 2017 / 66

Mark D. Gershman, MD1; Kristina M. Angelo, DO1; Julian Ritchey, MBA2; David P. Greenberg, MD2; Riyadh D. Muhammad, MD2; Gary Brunette, MD1; Martin S. Cetron, MD1; Mark J. Sotir, PhD1 (View author affiliations)

Summary

What is already known about this topic?Effective and safe yellow fever vaccines are available to prevent yellow fever disease among persons traveling to countries with yellow fever virus transmission and to comply with individual country yellow fever vaccination entry requirements; only one yellow fever vaccine (YF-VAX) is currently licensed for use in the United States. Periodic, temporary yellow fever vaccine shortages have occurred in the United States as a result of manufacturing problems, including a manufacturing complication in 2016 that resulted in the loss of a large number of U.S.-licensed yellow fever vaccine doses.

What is added by this report?To avoid a lapse in yellow fever vaccine availability to persons in the U.S. population for whom yellow fever vaccination is indicated, public health officials and private partners collaborated in pursuing an expanded access investigational new drug (eIND) application for the importation of Stamaril yellow fever vaccine into the United States. Stamaril is produced by Sanofi Pasteur, the manufacturer of the U.S.-licensed YF-VAX, and it uses the same vaccine substrain. A systematic, tiered process was developed to select clinics to participate in the eIND protocol, with the goal of reasonable accessibility to yellow fever vaccination for all U.S. residents, while assuring that clinic personnel could be adequately trained to participate in the protocol.

What are the implications for public health practice?Providers need to be aware that there is a yellow fever vaccine shortage and there is a plan for providing safe vaccine at a limited number of clinics until the supply is replenished. Domestic production of yellow fever vaccine in the United States should resume in 2018, and as the eIND protocol is implemented, CDC and Sanofi Pasteur will need to continue to collaborate throughout site recruitment and training, partner to resolve issues that arise, and maintain communication with health care providers and the general public.

Recent manufacturing problems resulted in a shortage of the only U.S.-licensed yellow fever vaccine. This shortage is expected to lead to a complete depletion of yellow fever vaccine available for the immunization of U.S. travelers by mid-2017. CDC, the Food and Drug Administration (FDA), and Sanofi Pasteur are collaborating to ensure a continuous yellow fever vaccine supply in the United States. As part of this collaboration, Sanofi Pasteur submitted an expanded access investigational new drug (eIND) application to FDA in September 2016 to allow for the importation and use of an alternative yellow fever vaccine manufactured by Sanofi Pasteur France, with safety and efficacy comparable to the U.S.-licensed vaccine; the eIND was accepted by FDA in October 2016. The implementation of this eIND protocol included developing a systematic process for selecting a limited number of clinic sites to provide the vaccine. CDC and Sanofi Pasteur will continue to communicate with the public and other stakeholders, and CDC will provide a list of locations that will be administering the replacement vaccine at a later date.

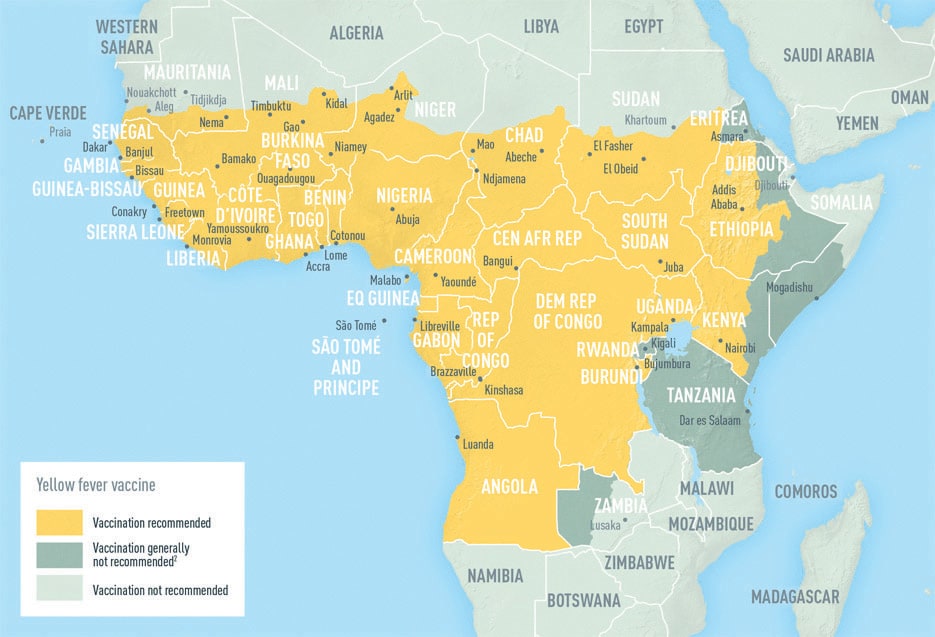

Yellow fever is an acute viral disease caused by infection with the yellow fever virus, a flavivirus primarily transmitted to humans through the bite of an infected mosquito and endemic to sub-Saharan Africa and tropical South America (1). Most infected persons are asymptomatic (1). However, the case-fatality ratio is 20%–50% among the approximately 15% of infected persons who develop severe disease (2). In recent years, multiple yellow fever outbreaks in Angola, the Democratic Republic of the Congo, and, most recently, Brazil, have underscored the ongoing and substantial global burden of this disease (3–5).

Yellow fever disease can be prevented by a live-attenuated virus vaccine that produces neutralizing antibodies in 80%–100% of vaccinees by 10 days after vaccination (2). For most travelers, only one lifetime dose is necessary (1). Vaccination is recommended for international travelers visiting areas with endemic or epidemic yellow fever virus transmission. In addition, proof-of-vaccination is required for entry into certain countries as permitted by the International Health Regulations 2015 (1,6). To provide proof of vaccination, practitioners at yellow fever vaccination clinics must validate a traveler’s vaccine record using a proof-of-vaccination stamp. CDC has regulatory authority over the designation of U.S. yellow fever vaccination clinics. For nonfederal yellow fever vaccination clinics, this authority to designate is generally delegated and overseen through a collaboration between CDC and state and territorial health departments. CDC maintains the online U.S. Yellow Fever Vaccination Center Registry of these designated clinics.

In 2015, approximately eight million U.S. residents traveled to 42 countries with endemic yellow fever virus transmission (1) (Data In, Intelligence Out [https://www.diio.net], unpublished data, 2016). Yellow fever virus can be exported by unimmunized travelers returning to countries where the virus is not endemic. Reports of yellow fever in at least 10 unimmunized returning U.S. and European travelers were recorded during 1970–2013 (1). Most recently, yellow fever virus was exported from Angola during the 2016 outbreak to three countries, with resulting local transmission in the Democratic Republic of the Congo (4). The Angola outbreak caused 965 confirmed cases from 2015 to 2017 (4). The ongoing outbreak in Brazil has resulted in 681 confirmed yellow fever cases from December 2016 through April 25, 2017 (7).

In the United States, only one yellow fever vaccine is licensed for use (YF-VAX; Sanofi Pasteur, Swiftwater, PA, 2017); approximately 500,000 doses are distributed annually to vaccinate military and civilian travelers. Approximately two thirds of these doses are distributed among approximately 4,000 civilian clinical sites (Sanofi Pasteur, unpublished data, 2017).

The current YF-VAX supply depletion began in November 2015 (8). Sanofi Pasteur was transitioning YF-VAX production from an older to a newer facility set to open in 2018, but a manufacturing complication resulted in the loss of a large number of doses. In response, Sanofi Pasteur instituted YF-VAX ordering restrictions to extend the existing supply while assessing options. In spring 2016, Sanofi Pasteur notified CDC of a probable complete depletion of YF-VAX later in the year. Sanofi Pasteur succeeded in producing additional doses of YF-VAX in late 2016; this additional supply has delayed the anticipated complete depletion until mid-2017 but remains insufficient to cover anticipated demand during the interval between permanent closure of the old facility and the 2018 opening of the new YF-VAX vaccine manufacturing facility.

Concerns about maintaining a continuous U.S. yellow fever vaccine supply, in conjunction with the large yellow fever outbreak that began in Angola, led to discussions among CDC, Sanofi Pasteur, FDA, and the U.S. Department of Defense in spring 2016. Although fractional yellow fever vaccine dosing was discussed, it was deemed a nonviable option based on limited efficacy data. Sanofi Pasteur submitted an eIND application for U.S. importation and civilian use of Stamaril, a yellow fever vaccine manufactured by Sanofi Pasteur France that is not licensed in the United States; the Department of Defense submitted its own eIND application. Stamaril uses the same vaccine substrain 17D-204 as YF-VAX, and has comparable safety and efficacy (9). Stamaril has been licensed and distributed in approximately 70 countries worldwide since 1986. Sanofi Pasteur France manufactures both multidose vials for use in global yellow fever outbreak responses and single-dose vials reserved for vaccination of international travelers living outside the United States. Sanofi Pasteur projects that importing Stamaril single-dose vials into the United States under the eIND application will not substantially affect the Stamaril supply intended for global use.

FDA accepted Sanofi Pasteur’s eIND application in October 2016. Implementation of the eIND protocol included a systematic process to select sites where Stamaril will be distributed; this process was important to manage the logistics involved in outreach and training of providers regarding adherence to the eIND protocol and FDA guidance. Sanofi Pasteur, in consultation with CDC, developed a two-tiered scheme for the selection of U.S. clinic sites to be invited to participate in the eIND protocol (Table). The primary goal was to recruit large-volume sites with adequate geographic range. Tier 1 sites were those that ordered at least 250 doses of yellow fever vaccine in 2016. Additional, smaller-volume sites were added to this tier to ensure access to Stamaril in all 50 states, the District of Columbia, and the three U.S. territories (Guam, Puerto Rico, and the U.S. Virgin Islands) with yellow fever vaccination centers. Sites were also added to guarantee vaccine access for civilian U.S. government employees needing yellow fever vaccination for official work-related travel, including critical public health response work. Tier 2 sites included multisite clinical organizations in which the aggregate number of doses ordered from their affiliated sites met the threshold of at least 250 doses in 2016. In these cases, the organization was invited to select one of its clinic sites to participate as a tier 2 site in implementing the Stamaril protocol. As of April 2017, approximately 250 clinics were targeted for inclusion. This is a sizable reduction from the estimated 4,000 civilian clinics currently providing YF-VAX.

The eIND protocol rollout began in April 2017. Sanofi Pasteur and CDC are collaborating to develop an effective communication plan. Sanofi Pasteur is recruiting and communicating with selected sites and will train personnel at participating sites by webinar in April and May 2017.

Discussion

CDC and Sanofi Pasteur have worked to assure a continuous yellow fever vaccine supply in the United States after the anticipated complete depletion of YF-VAX in mid-2017. As the eIND protocol rollout begins in April, Sanofi Pasteur will coordinate site recruitment and training, and CDC will help to resolve any problems that arise. Although the systematic site selection process for the distribution of Stamaril took into account site volume (giving preference to larger sites) and adequate geographic reach, accessibility difficulties for some international travelers might occur, because of the decrease in the number of clinics nationwide that provide yellow fever vaccination from 4,000 to 250. CDC and Sanofi Pasteur will monitor for critical gaps in vaccine access and collaborate to address any issues, including considering the possibility of recruiting additional clinics to participate as necessary.

CDC will notify state and territorial health department immunization programs about the Stamaril protocol. Information about which clinics will be eligible to receive Stamaril will be available to the public and other stakeholders, and discussed with the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices. CDC and Sanofi Pasteur continue to monitor the domestic yellow fever vaccine supply and will provide updates to health care providers and the public as new information becomes available.

Updates regarding yellow fever vaccine and the anticipated complete depletion of vaccine stock will be available on CDC’s Travelers’ Health website at https://wwwnc.cdc.gov/travel/ and Sanofi Pasteur’s website at http://www.sanofipasteur.us/vaccines/yellowfevervaccine. Once available, CDC will provide a complete list of clinics where travelers can receive Stamaril at https://wwwnc.cdc.gov/travel/yellow-fever-vaccination-clinics/search.

References

- Gershman MD, Staples JE. Yellow fever. In: Brunette GW; CDC, eds. CDC health information for international travel 2016. New York, NY: Oxford University Press; 2016.

- Staples JE, Gershman M, Fischer M. Yellow fever vaccine: recommendations of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP). MMWR Recomm Rep 2010;59(No. RR-7). PubMed

- World Health Organization. Emergency preparedness, response: yellow fever. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization; 2017. http://www.who.int/csr/don/archive/disease/yellow_fever/en/

- World Health Organization. Yellow fever outbreak Angola, Democratic Republic of the Congo and Uganda 2016–2017. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization; 2017. http://www.who.int/emergencies/yellow-fever/en/

- World Health Organization. Brazil works to control yellow fever outbreak, with PAHO/WHO support. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization; 2017. http://www2.paho.org/hq/index.php?option=com_content&view=article&id=13098%3Abrazil-control-yellow-fever-outbreak-paho-support&catid=740%3Apress-releases&Itemid=1926&lang=en

- World Health Organization. International health regulations, 2005. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization; 2008. http://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/10665/43883/1/9789241580410_eng.pdf

- Pan American Health Organization. Epidemiological update yellow fever. Washington, DC: Pan American Health Organization; 2017. http://www2.paho.org/hq/index.php?option=com_docman&task=doc_view&Itemid=270&gid=39639&lang=en

- CDC. Announcement: yellow fever vaccine shortage. Atlanta, GA: US Department of Health and Human Services, CDC; 2016. https://wwwnc.cdc.gov/travel/news-announcements/yellow-fever-vaccine-shortage-2016

- Plotkin S, Orenstein WA, Offit PA, eds. Vaccines. 6th ed. Philadelphia: Elsevier Saunders; 2013.

TABLE. Systematic tiered distribution plan for Stamaril yellow fever vaccine — United States, 2016

| Tier | Characteristic | No. of proposed sites |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Individual sites that ordered at least 250 doses in 2016 | 193 |

| Smaller sites to ensure coverage of all 50 states, DC, and U.S. territories | ||

| Sites that serve non-military U.S. government employees | ||

| 2 | Sites that are part of a multisite clinical organization whose aggregate number of orders was at least 250 doses in 2016 | 59 |

| Total | 252 | |

Abbreviation: DC = District of Columbia.

Suggested citation for this article: Gershman MD, Angelo KM, Ritchey J, et al. Addressing a Yellow Fever Vaccine Shortage — United States, 2016–2017. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. ePub: 28 April 2017. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.15585/mmwr.mm6617e2.

More than 18.8 million doses of yellow fever vaccine have been distributed in Brazil since January.

Thursday, March 30th, 2017Brazil Works to Control Yellow Fever Outbreak, with PAHO/WHO support

Washington, D.C., March 28, 2017 (PAHO/WHO)—Brazil is carrying out mass vaccination campaigns for yellow fever in the states of Minas Gerais, Espirito Santo, Sao Paulo, Rio de Janeiro and Bahia, while strengthening surveillance and case management throughout the country since an outbreak of sylvatic yellow fever began in January. More than 18.8 million doses of vaccine have been distributed, in addition to routine immunization efforts.

The Pan American Health Organization/World Health Organization (PAHO/WHO) is providing specialized technical cooperation to the federal authorities managing the outbreak and has mobilized more than 15 experts, including experts from the Global Outbreak Alert and Response Network (GOARN), in disease control, surveillance, virology, immunization and other fields to collaborate with health officials in the affected states. These experts have been operating with field teams in surveillance, response, and control operations in Minas Gerais, Espirito Santo and Rio de Janeiro States.

Brazil’s Ministry of Health has reported 492 confirmed cases of yellow fever as of March 24, with 162 confirmed deaths. Another 1101 suspected cases are under investigation. A total of 1,324 epizootics, or deaths from yellow fever in primates, have been reported to the Ministry of Health, and 387 of these were confirmed by laboratory or epidemiological link, while 432 others are still being investigated.

So far, in the four states with confirmed yellow fever human cases– Minas Gerais, Espírito Santo, Rio de Janeiro and São Paulo– all cases have been linked to transmission through the jungle mosquito species Haemagogus and Sabethes. But confirmed cases in humans and monkeys in municipalities close to large urban areas indicate a potential risk of urbanization, and yellow fever activity has increased in ecosystems of tropical and sub-tropical forests that are close to human populations.

Officials are working to contain the virus so it does not spread to cities where it could infect Aedes aegypti urban mosquitoes. Until now there is no evidence of human cases of yellow fever virus infection transmitted by that mosquito.

Case numbers have been declining in Minas Gerais and Espirito Santo, but close monitoring of cases is continuing and Brazil is strengthening its capacity to quickly detect and treat cases of yellow fever. Vector-borne diseases have a seasonal characteristic in tropical areas and it is expected that new cases will diminish during dry and cold weather seasons.

Vaccination

Yellow fever can be prevented by means of an effective, and affordable live attenuated virus vaccine. PAHO/WHO recommends only one dose of the vaccine, which is sufficient to confer sustained immunity and life-long protection against yellow fever disease. The yellow fever vaccine is contraindicated in seriously immunosuppressed individuals. People over the age of 60 should only receive a vaccine after a careful risk-benefit assessment. The yellow fever vaccine should not be given to pregnant women, except those with high risk of infection and situations where there is an express recommendation from health authorities, or to infants aged less than 6 months, or to people with acute febrile illness.

PAHO/WHO currently recommends that countries prioritize, for vaccination, populations living in endemic areas and travelers to these areas, and that they expand vaccination to the routine vaccination of children at the national level if vaccines were available. It is important that countries share YF vaccination coverage estimates at the local level for children and adults in order to inform an accurate risk assessment of the current situation.

Mass immunization campaigns have started in the affected states. Federal public health authorities in Brazil have distributed 18.8 million doses of yellow fever vaccine since January to the states and municipalities in the areas where cases have been reported. These include the states of Minas Gerais, Espírito Santo, São Paulo, Bahia, and Rio de Janeiro. This effort is in addition to the country’s routine yellow fever vaccine programs in 19 states, which included 3.7 million doses of vaccine.

The extra vaccines include 3.5 million doses of yellow fever vaccine that Brazil requested from the emergency stockpile held by the International Coordinating Group (ICG) on Vaccine Provision, and have arrived in the country. The ICG includes four agencies: the World Health Organization (WHO), United Nations Children’s Fund (UNICEF), the International Federation of Red Cross and Red Crescent Societies (IFRC), and Médecins Sans Frontières (MSF).

The WHO Secretariat recommends vaccination against yellow fever at least 10 days prior to travel for travelers going to areas in Brazil where there is risk of yellow fever transmission, including the State of Rio de Janeiro, with the exception of the urban areas of Rio de Janeiro City and Niterói, and the State of São Paulo, with the exception of the urban areas of São Paulo City and Campinas. The WHO Secretariat recommends vaccination in the whole states of Espirito Santo and Minas Gerais. The information is being continuously updated.

Yellow fever in the Americas

Sylvatic Yellow Fever is endemic in areas of 13 countries and territories of the region, including Argentina, Brazil, Paraguay, Bolivia, Peru, Ecuador, Colombia, Venezuela, Panama, Guyana, Surinam, French Guiana and the island of Trinidad. In Brazil, 21 of the 27 states and the Federal District are considered to have areas at risk for Yellow Fever transmission. Globally, 47 countries have areas with endemic yellow fever: 34 in Africa, and 13 in Central and South America. Mass immunization is the most effective way to prevent disease.

LINKS

— Epidemiological update on Yellow Fever (March 23)

— Updated requirements for the International Certificate of Vaccination or Prophylaxis (ICVP) with proof of vaccination against yellow fever (March 22 2017)

— PAHO/WHO Yellow Fever

— Updates on yellow fever vaccination recommendations for international travelers related to the current situation in Brazil

— Yellow Fever fact sheet

— Brazil Ministry of Health, Situation report on the yellow fever outbreak

The Netherlands reports a case of yellow fever from Suriname

Wednesday, March 29th, 2017Yellow fever – Suriname

On 9 March 2017, the National Institute for Public Health and the Environment (RIVM) in the Netherlands reported a case of yellow fever to WHO. The patient is a Dutch adult female traveller who visited Suriname from the middle of February until early March 2017. She was not vaccinated against yellow fever.

The case was confirmed for yellow fever in the Netherlands by RT-PCR in two serum samples taken with an interval of three days at the Erasmus University Medical Center (Erasmus MC), Rotterdam. The presence of yellow fever virus was confirmed on 9 March 2017 by PCR and sequencing at Erasmus MC, and by PCR on a different target at the Bernhard Nocht Institute for Tropical Medicine, Hamburg, Germany.

While in Suriname, the patient spent nights in Paramaribo and visited places around Paramaribo, including the districts of Commewijne (Frederiksdorp and Peperpot) and Brokopondo (Brownsberg), the latter is considered to be the most probable place of infection. She experienced onset of symptoms (headache and high fever) on 28 February 2017 and was admitted to an intensive care unit (University Medical Center) in the Netherlands on 3 March 2017 with liver failure. The patient is currently in critical condition.

Suriname is considered an area at risk for yellow fever and requires a yellow fever vaccination certificate at entry for travellers over one year of age arriving from countries with risk of yellow fever, according to the WHO list of countries with risk of yellow fever transmission; WHO also recommends yellow fever vaccination to all travellers aged nine months and older. This is the first reported case of yellow fever in Suriname since 1972.

Public health response

This report of a yellow fever case in the Netherlands with travel history to Suriname has triggered further investigations. Following this event, health authorities in Suriname have implemented several measures to investigate and respond to a potential outbreak in their country, including:

- Enhancing vaccination activity to increase vaccination coverage among residents. Suriname will continue with its national vaccination programme and will focus on the district of Brokopondo. A catch-up vaccination campaign is also being conducted to increase coverage in Brownsweg.

- Enhancing epidemiologic and entomologic surveillance including strengthening laboratory capacity.

- Implementing vector control activities in the district Brokopondo.

- Carrying out a survey of dead monkeys in the suspected areas.

- Conducting social mobilization to eliminate Aedes aegypti breeding sites (e.g. by covering water containers/ barrels).

- Issuing a press release to alert the public.

- Mapping of the suspect area of Brownsweg, as well as the Peperpot Resort.

WHO risk assessment

Yellow fever is an acute viral haemorrhagic disease that has the potential to spread rapidly and cause serious public health impact in unimmunized populations. Vaccination is the most important means of preventing the infection.

Suriname is a country with a risk of yellow fever transmission in endemic areas. Vaccination is recommended before travelling to Suriname for all travellers aged nine months and older. Suriname requires proof of vaccination against yellow fever for all travellers over one year of age.

Suriname introduced the yellow fever vaccination into the routine program for all children aged one years old in 2014.The estimate of national immunization coverage is 86% and only includes children aged one years old. The unvaccinated populations living in the endemic areas are at high risk of yellow fever infection.

The current report of a travel-associated case provides evidence to consider local transmission of yellow fever in the country. More investigations are also needed for animal health sectors.

In addition, Suriname shares borders with Brazil, which has been experiencing yellow fever outbreaks since January 2017 (the largest outbreak of yellow fever in the Americas in the past three decades).

Sequencing and comparison to cases from various other countries is still ongoing, but it is likely that the case is not related to the yellow fever outbreak in Brazil.

As South America is currently experiencing a cyclical increase in the number of cases in non-human primates and human cases, an increase in the number of cases in unvaccinated travellers returning from affected areas in South America is not unexpected. The risk of spread of the disease by non-immunized travellers from Suriname to the countries that have the vector for the transmission of the yellow fever virus is considered to be low but cannot be ruled out.

Currently, five countries in South America report yellow fever virus activity: Brazil, Bolivia, Peru, Colombia and Ecuador. This multi-country yellow fever virus activity might reflect current, wide-spread ecological conditions that favour elevated yellow fever virus transmissibility among wildlife and spill-over to humans. The sequencing analysis of currently circulating strains in Brazil, Bolivia, Colombia, Peru, Ecuador and Suriname should provide insight whether the human cases in these countries are epidemiologically linked or represent multiple, independent spill-over events without extensive ongoing community transmission.

WHO advice

Advice to travellers planning to visit areas at risk for yellow fever transmission in Brazil includes:

- Vaccination against yellow fever at least 10 days prior to the travel. A single dose of yellow fever vaccine is sufficient to confer sustained immunity and life-long protection against yellow fever disease and a booster dose of the vaccine is not needed;

- Travellers with contraindications for yellow fever vaccine (children below nine months, pregnant or breastfeeding women, people with severe hypersensitivity to egg antigens, and severe immunodeficiency) or over 60 years of age should consult their health professional for advice based on risk benefit analysis;

- Observation of measures to avoid mosquito bites;

- Awareness of symptoms and signs of yellow fever;

- Promotion of health care seeking behaviour while travelling and upon return from an area at risk for yellow fever transmission, especially to a country where the establishment of a local cycle of transmission is possible (i.e. where the competent vector is present).

- Seeking care in case of symptoms and signs of yellow fever, while travelling and upon return from areas at risk for yellow fever transmission.

This case report illustrates the importance of yellow fever vaccination for travellers to countries with risk of yellow fever virus transmission, even for countries that have not reported cases for decades.

WHO, therefore, urges Members States to comply with the requirement for yellow fever vaccination for travellers to certain countries and the recommendation for all travellers to countries or areas with risk of yellow fever transmission (see ‘Yellow fever vaccination requirements and recommendations; malaria situation; and other vaccination requirements – List of countries, territories and areas’ in related links). Viraemic returning travellers may pose a risk for the establishment of local cycles of yellow fever transmission predominantly in areas where the competent vector is present. If there are medical grounds for not getting vaccinated, this must be certified by the appropriate authorities.

WHO does not recommend that any general travel or trade restriction be applied on Suriname based on the information available for this event.

Despite fewer cases, Brazil has confirmed 2 cases of yellow fever in a city just 83 miles away from Rio de Janeiro.

Tuesday, March 21st, 2017Yellow fever is a mosquito-borne viral infection present in some tropical areas of Africa and South America.

In South America, there are two transmission cycles of yellow fever:

– A sylvatic cycle, involving transmission of the virus between Haemagogus or Sabethes mosquitoes and primates. The virus is transmitted by mosquitoes from primates to humans when humans are visiting or working in the forest.

– An urban cycle, involving transmission of the virus between Aedes aegypti mosquitoes and humans. The virus is usually introduced in an urban area by a viraemic human who was infected in the forest.

Brazil has been experiencing an outbreak of yellow fever since December 2016. The outbreak was notified on 6 January 2017.

|

Between 6 and 16 March 2017, Brazil reported 20 additional cases of yellow fever, mostly in Espírito Santo and Minas Gerais. On 15 March 2017, the state of Rio de Janeiro reported its two first confirmed autochthonous cases in the municipality of Casimiro de Abreu, located 135 km from the city of Rio de Janeiro.

On 10 March 2017, the Netherlands reported a confirmed case of yellow fever in a traveller returning from Suriname. During week 10 of 2017, Ecuador reported a confirmed case of yellow fever in the province of Sucumbios, which borders Colombia. Prior to this case, the last confirmed yellow fever case in Ecuador was reported in 2012 in the province of Napo. Epidemiological Summary

On 6 January 2017, Brazil reported an outbreak of yellow fever. The index case had onset of symptoms on 18 December 2016. The first laboratory confirmation was notified on 19 January 2017.

Between 6 January and 16 March 2017, Brazil has reported 1 357 cases (933 suspected and 424 confirmed), including 249 deaths (112 suspected and 137 confirmed). The case-fatality rate is 18.3% among all cases and 32.3% among confirmed cases. States reporting suspected and confirmed autochthonous cases: – Minas Gerais has reported 1 074 cases (749 suspected and 325 confirmed), including 189 deaths (78 suspected and 111 confirmed). – Espírito Santo has reported 243 cases (150 suspected and 93 confirmed), including 48 deaths (26 suspected and 22 confirmed). – São Paulo has reported 15 cases (11 suspected and four confirmed), including four deaths (one suspected and three confirmed). – Rio de Janeiro has reported three cases (one suspected and two confirmed), including one confirmed death. States reporting suspected autochthonous cases: – Bahia has reported eight suspected cases, including one fatal. – Tocantins has reported six suspected cases, including one fatal. – Rio Grande do Norte has reported one suspected case, fatal. – Goiás has reported three suspected cases, not fatal. In addition, investigations are ongoing to determine the probable infection site of four further suspected cases. On 16 March 2017, authorities in the state of Rio de Janeiro identified 47 municipalities as a priority for the vaccination campaign, including the municipality of Casimiro de Abreu, where the two confirmed cases are reported. The Ministry of Health of Brazil has launched mass vaccination campaigns in addition to routine vaccination activities. As of 16 March 2017, 16.15 million extra doses of yellow fever vaccine had been sent to five states: Minas Gerais (7.5 million), São Paulo (3.25 million), Espírito Santo (3.45 million), Rio de Janeiro (1.05 million) and Bahia (900 000). |

“….As we have seen with dengue, chikungunya, and Zika, A. aegypti–mediated arbovirus epidemics can move rapidly through populations with little preexisting immunity and spread more broadly owing to human travel. Although it is highly unlikely that we will see yellow fever outbreaks in the continental United States, where mosquito density is low and risk of exposure is limited, it is possible that travel-related cases of yellow fever could occur, with brief periods of local transmission in warmer regions such as the Gulf Coast states, where A. aegypti mosquitoes are prevalent…..”

Sunday, March 19th, 2017

“….The clinical illness manifests in three stages: infection, remission, and intoxication.

- During the infection stage, patients present after a 3-to-6-day incubation period with a nonspecific febrile illness that is difficult to distinguish from other flulike diseases.

- High fevers associated with bradycardia, leukopenia, and transaminase elevations may provide a clue to the diagnosis, and patients will be viremic during this period.

- This initial stage is followed by a period of remission, when clinical improvement occurs and most patients fully recover.

- However, 15 to 20% of patients have progression to the intoxication stage, in which symptoms recur after 24 to 48 hours. This stage is characterized by high fevers, hemorrhagic manifestations, severe hepatic dysfunction and jaundice (hence the name “yellow fever”), renal failure, cardiovascular abnormalities, central nervous system dysfunction, and shock. ……

- Case-fatality rates range from 20 to 60% in patients in whom severe disease develops, and

- [T]reatment is supportive, since no antiviral therapies are currently available…..”