At least 133 people have died and more than 200 others have been hospitalized after consuming tainted alcohol in India

February 24th, 2019“…..Homemade alcohol is typically brewed in villages before being smuggled into cities, where it sells for about 10 cents a glass — about a third the price of legally brewed liquor…….

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=XUJsu5v-Vig

Human Brucella abortus RB51 Infections and the Consumption of Unpasteurized Domestic Dairy Products — United States, 2017–2019.

February 24th, 2019Negrón ME, Kharod GA, Bower WA, Walke H. Notes from the Field: Human Brucella abortus RB51 Infections Caused by Consumption of Unpasteurized Domestic Dairy Products — United States, 2017–2019. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2019;68:185. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.15585/mmwr.mm6807a6.

“……Since August 2017, CDC has confirmed three cases of brucellosis attributed to Brucella abortus cattle vaccine strain RB51 (RB51). Each case was associated with consumption of domestically acquired unpasteurized (raw) milk products (1). Patient symptoms varied and included fever, headache, overall malaise, and respiratory symptoms. In total, at least eight persons met the probable case definition of a clinically compatible illness epidemiologically linked to a shared contaminated source …..”

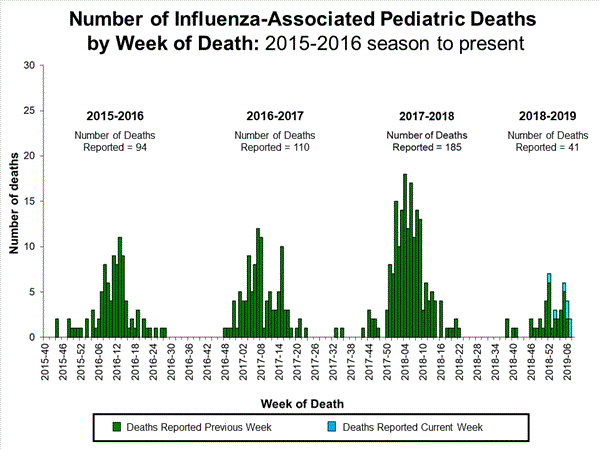

2018-2019 Influenza Season Week 7 ending February 16, 2019: Influenza activity continues to increase in the United States.

February 23rd, 20192018-2019 U.S. Flu Season: Preliminary Burden Estimates from October 1, 2018, through February 16, 2019

February 23rd, 2019CCDC estimates that, from , there have been:

CDC

* 17.7 million – 20.4 million flu illnesses

![]()

- 8.2 million – 9.6 million flu medical visits

- 214,000 – 256,000 flu hospitalizations

- 13,600 – 22,300 flu deaths

U.S.: Infectious Diseases Occurring in Workplaces

February 23rd, 2019Su C, de Perio MA, Cummings KJ, McCague A, Luckhaupt SE, Sweeney M. Case Investigations of Infectious Diseases Occurring in Workplaces, United States, 2006–2015. Emerg Infect Dis. 2019;25(3):397-405. https://dx.doi.org/10.3201/eid2503.180708

Reported case investigations of infectious disease occurring in workplaces, by industry categories, occupations, and diseases, United States, 2006–2015*

| Industry category (NAICS code) | Occupations | Infectious diseases | References† |

|---|---|---|---|

| Agriculture, forestry, fishing, and hunting (11) | Hunter | Brucellosis | (61) |

| Farmer | Variant influenza A(H3N2); Escherichia coli infection | (83); (71) | |

|

|

Rodent breeder

|

LCMV infection

|

(82)

|

| Construction (23)

|

Laborer

|

Coccidioidomycosis

|

(23,25)

|

| Manufacturing (31–33) | Drum maker | Anthrax | (2) |

| Poultry vaccine production worker | Salmonellosis | (29) | |

| Poultry-processing worker | Campylobacteriosis | (17) | |

| Furniture company worker | Tuberculosis | (54) | |

| Slaughterhouse inspector | Q fever | (65) | |

|

|

Automobile manufacturing worker

|

Legionnaires’ disease

|

(81)

|

| Transportation (48) | Truck driver | Streptococcus suis infection; cryptosporidiosis | (79); (88) |

|

|

Pilot, flight attendant

|

Malaria

|

(37)

|

| Professional, scientific, and technical services (54)

|

Laboratory worker

|

Vaccinia virus infection, HIV infection, plague, cowpox, meningococcal disease, brucellosis

|

(13,30–35,86)

|

| Administrative support and waste management and remediation services (56)

|

Landscaper

|

Tularemia

|

(21)

|

| Education services (61)

|

School employee, teacher

|

Influenza

|

(8)

|

| Healthcare and social assistance (62) | Healthcare worker (security guard, nurse, nursing aide, physician, volunteer, environmental services) | Mumps; MRSA skin infection; norovirus gastroenteritis; adenovirus 14 infection; RSV infection; Trichophyton tonsurans skin infection; meningococcal disease; influenza; salmonellosis; Ebola virus disease; measles; TB | (51); (52); (56); (57); (62); (64); (66); (11,68); (87); (14); (92); (12,77) |

|

|

Childcare worker

|

E. coli infection

|

(72)

|

| Arts, entertainment, and recreation (71) | Wildlife biologist | Plague | (59) |

| Animal caretaker | MRSA skin infection | (63) | |

| Adult film performer | HIV infection | (36) | |

| Spa maintenance worker | MAC infection | (22) | |

| Filmmaker | Coccidioidomycosis | (24) | |

|

|

Day camp counselor

|

Histoplasmosis

|

(26)

|

| Food services (72)

|

Cook, food server

|

Norovirus gastroenteritis; salmonellosis; E. coli infection

|

(20); (19);

(89)

|

| Other services except public administration (81) | Embalmer | TB | (16) |

| Animal refugee worker | Tuberculosis; sealpox virus infection | (28); (18) | |

| Pet store worker | Salmonellosis | (74) | |

|

|

Missionary worker

|

Melioidosis; dengue fever

|

(75); (70)

|

| Public administration (92) | US Customs officer | Measles | (9,10) |

| Police officer | Meningococcal disease | (66) | |

| Firefighter | Cryptosporidiosis | (88) | |

| Correctional officer | Cryptosporidiosis; Shiga toxin–producing E. coli infection; TB; coccidioidomycosis; | (78); (71); (12); (90) | |

| Military | Legionellosis; TB | (73); (53) |

*An expanded version of this table showing complete details on all cases is available online (https://wwwnc.cdc.gov/EID/article/25/3/18-0708-T1.htm). HIV, human immunodeficiency virus; LCMV, lymphocytic choriomeningitis virus; MAC, Mycobacterium avium complex; MRSA, methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus; RSV, respiratory syncytial virus; TB, tuberculosis. NAICS, 2012 North American Industry Classification System (https://www.census.gov/eos/www/naics/).

†Reference numbers >50 and additional details on the literature search are available in the Appendix.

Holocaust in a bazaar in Dhaka

February 22nd, 2019“…..A car powered by compressed natural gas was traveling through a bazaar in Dhaka, Bangladesh’s capital, when the cylinder stored in the back exploded…..

The blast flipped the car. It then ignited several other cylinders that were being used at a street-side restaurant. Then a plastics store on the ground floor of a nearby building caught fire. Then a small shop that was illegally storing chemicals burst into flames.

A wall of fire surged across the street, engulfing bicycles, rickshaws, cars, people, everything in its path. The inferno claimed at least 70 lives….”

Hypothermia and Death in the U.S.

February 22nd, 2019QuickStats: Death Rates Attributed to Excessive Cold or Hypothermia Among Persons Aged ≥15 Years, by Urbanization Level and Age Group — National Vital Statistics System, 2015–2017. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2019;68:187. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.15585/mmwr.mm6807a8.

“…..During 2015–2017, death rates attributed to excessive cold or hypothermia increased steadily with age among those aged ≥15 years in both metropolitan and nonmetropolitan counties. The rate for persons aged ≥85 years reached 3.8 deaths per 100,000 in metropolitan counties and 7.3 in nonmetropolitan counties. The lowest rates were among those aged 15–24 years (0.2 in metropolitan counties and 0.5 in nonmetropolitan counties). In each age category, death rates were lower in metropolitan counties and higher in nonmetropolitan counties.

Source: National Center for Health Statistics, National Vital Statistics System, Mortality Data 2015–2017……”

Enteroinvasive Escherichia coli Outbreak Associated at a Potluck in North Carolina

February 22nd, 2019Herzig CT, Fleischauer AT, Lackey B, et al. Notes from the Field: Enteroinvasive Escherichia coli Outbreak Associated with a Potluck Party — North Carolina, June–July 2018. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2019;68:183–184. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.15585/mmwr.mm6807a5.

“On July 2, 2018, the North Carolina Division of Public Health was notified that approximately three dozen members of an ethnic Nepali refugee community had been transported to area hospitals for severe gastrointestinal illness after attending a potluck party on June 30. The North Carolina Division of Public Health partnered with the local health department and CDC to investigate the outbreak, identify the cause, and prevent further transmission. The investigation included molecular-guided laboratory testing of clinical specimens by CDC, which determined that this was the first confirmed U.S. outbreak of enteroinvasive Escherichia coli (EIEC) in 47 years.

A case was defined as the occurrence of diarrhea, vomiting, or fever ≥101°F (38.3°C) in a person who consumed food served at the party. Cases were identified through medical record review and retrospective cohort investigation with convenience sampling of party attendees. Among approximately 100 attendees, 52 met the case definition. Median age was 31 years (range = 3–76 years); 28 (54%) were hospitalized, including 13 (25%) with sepsis, and eight (15%) who were admitted to an intensive care unit. All patients recovered, and no secondary cases were identified.

Forty-nine persons, including 35 who were ill, were interviewed using a questionnaire to ascertain symptoms, recent travel, and food exposures. Participants also were provided with hand hygiene guidance. Among the 35 ill persons, 30 (86%) reported symptom onset on July 1, the day after the event (Figure). Median interval between eating and symptom onset was 20.5 hours (range = 1–45.5 hours). Overall, 33 (94%) ill persons experienced diarrhea, including 27 (77%), 19 (54%), and two (6%) who reported diarrhea that was watery, mucoid, or bloody, respectively. Thirty-two (91%) ill persons reported fever.

Participants reported eating chicken curry, vegetable curry, rice, lentil soup, fried bread, cold and hot salads, and cake; no imported foods were reported. No single food item was statistically significantly associated with illness; however, 37 persons reported eating chicken curry, and those who did had a 47% higher risk for illness than those who did not (risk ratio = 1.47; 95% confidence interval = 0.76–2.83). No food was available for testing…..”

Social Media Reactions to an Errant Warning of a Ballistic Missile Threat

February 22nd, 2019Murthy BP, Krishna N, Jones T, Wolkin A, Avchen RN, Vagi SJ. Public Health Emergency Risk Communication and Social Media Reactions to an Errant Warning of a Ballistic Missile Threat — Hawaii, January 2018. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2019;68:174–176. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.15585/mmwr.mm6807a2.

“……A total of 127,125 tweets were identified; after excluding 69,151 (54%) retweets and 43,444 (34%) quote tweets, 14,530 (11%) initial tweets remained for analysis. Among these, 5,880 (40%) were sent during the early period, and 8,650 (60%) were sent during the late period……”

* 8:07–8:45 a.m. Hawaii Standard Time.

† 8:46–9:24 a.m. Hawaii Standard Time (additional themes identified in addition to those in the early period).

What is already known about this topic?

Social media platforms are widely used to share information and disseminate alerts and warnings.

What is added by this report?

After an errant ballistic missile alert, social media reactions revealed how the public interprets, shares, and responds to information during an evolving threat. This knowledge can guide emergency risk communicators to develop timely and effective social media messages than can protect lives.

What are the implications for public health practice?

Social media can be an effective tool to send urgent messages during a public health emergency. Public health practitioners need to improve messaging during emergency risk communications to address the public’s needs during each phase of an unfolding crisis to protect and save lives

Ontario, Canada: Listeria monocytogenes Associated with Pasteurized Chocolate Milk

February 22nd, 2019Hanson H, Whitfield Y, Lee C, Badiani T, Minielly C, Fenik J, et al. Listeria monocytogenes Associated with Pasteurized Chocolate Milk, Ontario, Canada. Emerg Infect Dis. 2019;25(3):581-584. https://dx.doi.org/10.3201/eid2503.180742

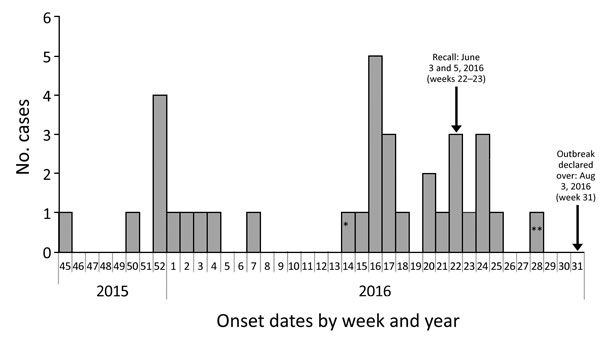

Figure 1. Outbreak cases of listeriosis (n = 34) by onset week and year, Ontario, Canada, November 2015–August 2016. Data were obtained from the Ontario Ministry of Health and Long-Term Care, integrated Public Health Information System database, extracted by Public Health Ontario, August 16, 2016. Weeks are defined according to the Public Health Agency of Canada epidemiologic week calendar. *Neonatal case-patient with symptom onset on April 4, 2016 (week 14), and illness most likely caused by mother-to-child transmission. **Asymptomatic case-patient from whom a specimen was collected on July 13, 2016, and exposure occurred before June 27, 2016 (week 28).

Figure 2. Bags of pasteurized chocolate milk as sold in Canada, with outer bag containing brand information removed. A bag of milk similar to these, found at the home of 1 case-patient during investigation of an outbreak of Listeria monocytogenes infection associated with pasteurized chocolate milk in Ontario, Canada, was found to be contaminated with the same strain obtained from infected patients.